Legend has it that when the Devil first came to Beirut, with his black Slayer t-shirt and long, greasy hair, he slipped into our school and strutted down the hallway like he owned the place. As he walked by, half the girls felt a chill run down their spines and rose brokenly from their desks like marionettes. They walked out of math and English, left metal rods dissolving in beakers of hydrochloric acid on chemistry tables — oblivious to the indignant shouts of their teachers — and stood silently in classroom doorways up and down the hall, watching him go by. I didn’t see him myself. All I remember was the mooning, hundred-lunged sigh that lifted my physics exam clear off my desk and out of the window, down along a shaft of cool air to the street, where it was shredded beneath the wheels of a passing car. I got a zero. The teacher called me a smart-ass when I told her my exam had taken off on its own.

Afterward, people pointed to proof of his continued presence: pentagrams scrawled on desks and walls, the anarchist “A” with a circle around it carved into a blackboard. An English assignment was handed in — I knew three people who swore it had happened in their class — consisting entirely of the words “Kurt Cobain lives” written over and over again. Bloody rags were found stuffed into garbage cans in the girls’ bathrooms; it was said that when the janitor emptied the garbage, one of the rags unrolled to reveal a tiny fetus. We’d just finished studying reproduction in biology. I imagined it whole and perfect with bulging, membrane-sheathed eyes and tadpole appendages, a map of veins visible beneath its translucent skin. But my friend Fadi insisted it would be a mangled clump, like discharge from a heavy period. (He lived with his mother and sister). Whatever it was, it was clearly a DIY abortion: a child sacrifice. A Nirvana mix tape was also found on a shelf nearby, two parts Nevermind, one part MTV Unplugged. This, more than the fetus, was deemed incontrovertible evidence. The news spread in whispers across the city. The girls in that school are bad—they belong to the Devil.

I knew it had gotten out of hand when my grandmother asked me about it.

“Teta, that music you’re listening to, it’s not devil-music, is it?”

“No, Teta,” I said. “It’s Tori Amos.”

“Why’s she screeching like that?”

“She’s angry,” I told her. “About men.”

My grandmother nodded her head and went back to coring her koussa.

“There’s a lot to be angry about,” she agreed. Then, after a pause, “Just be careful. Men never want to marry angry girls.”

This was fifteen years ago, just about. At the time we used to go to this bar on the east side where we could sit in bamboo chairs under the open sky and order apple arguilehs and cheap, watered-down shots. I’m not sure what was a bigger rush, the illicit liquor or the journey east. The civil war had just ended and we still weren’t used to this new city grown overnight out of the dead ends of the old one. We drove recklessly in our parents’ Datsuns and Volvos without licenses, past the ghosts of militiamen and the sad, broken-down relics of their checkpoints. It seemed like the beginning of something endless, a whole new city, bruised but united; our lives.

One night, we were all at the cheap-shots place: me, Omar, Michael, and Fadi. It was early spring just before senior year, and the night was sweet-scented and encrusted with stars, a self-contained pocket in space-time. We were talking over each other as usual, each person braying louder than the next until Omar got self-conscious and shut us up. Then we built the decibel level back up again. I turned away for a second to pull a battered cigarette from beneath the pile of textbooks in my bag. That’s when I saw him. He was pale and awfully thin, but he had these amazing, deeply-etched half-moon dimples. He looked up and caught me staring. Gave me a wink and a wicked smile, like he knew exactly what I was thinking and was with me on everything. I could barely breathe.

“Look,” I said, trying to catch the boys’ attention. “It’s him.”

When I looked back again, he was gone.

At the beginning of senior year, I developed a crush on a boy who liked evil girls. Not evil-evil, but self-sufficient and prickly, quick with a Zippo, a sneer, and a comeback. The sorts of girls who were evil to me. If the Devil was around, I figured, maybe he could help, because the other guy sure wasn’t listening to my prayers to make the boy like me. At worst, I would pick up some of his devilish charm, which might help my much-lacking bad-girl image.

I approached Nadine, one of the girls in my class.

“Do you know how to make a Ouija board?” She seemed like the person most likely to know something like that. I’d seen her wearing an Iron Maiden t-shirt several times the year before.

“Sure,” she replied. “All you need is some cardboard, a marker, and a bottle cap. I saw it on one of those Mexican soaps.”

We waited until Nadine’s younger brother was out and snuck into his room, on the theory that his Metallica posters and the papier-mâché effigy of Kurt Cobain would be more conducive than the pink-and-purple color scheme in her bedroom. We lit candles, turned off the lights, and sat, fingertips fluttering in anticipation. She did all the talking.

“O Spirit,” she asked, in a loud, authoritative voice. “Are you here?”

The bottle cap trembled, swept over to “No,” then quickly to “Yes” and slowly back to

“No.”

“Oh, wow,” I breathed. “It’s really real! It’s moving!” She smiled at me smugly.

“Spirit,” she continued, “can you tell us if this boy likes Lina?” She pointed to a yearbook photo of the boy in question.

Again the “No-Yes-No” swing, so fast this time my fingers could barely keep up.

“Having trouble making up his mind,” I muttered. “Shh!” she warned. “You have to stay focused!”

“Spirit,” she continued in her loud voice, “what can Lina do to make this boy like her?”

R-U-J-U-I, it spelled.

“What the hell does that mean?” I hissed. “Quiet,” she said. “Maybe it’s the boy’s mother’s maiden name.”

“I’ve never heard of Beit Rujui.” My confidence in the whole thing was flagging.

“Well, then, maybe he’s not in the mood. Shit, we should have asked him first if he minds being bothered. It’s more polite.”

“O Spirit,” looking out into the middle distance, serious as can be, “are your intentions good? Are you pleased to be among us?”

The bottle cap trembled and swung decisively to “No.”

“Oh fuck! Let’s get out of here!” she shrieked.

We made a mad dash for the lights, put out all the candles, and crumpled up our makeshift Ouija board, tossing it out Nadine’s fifth-floor window along with the bottle cap and marker.

“Why are we bothering with his minions? Maybe we should just find the Devil and ask him in person,” she suggested, after we’d stopped our hysterical giggling.

“Really?” I asked. “You know where he hangs out?”

“Sure,” she said. “Everybody does. Friday, Saturday, he’s always at American Dream, watching the metal bands. Sometimes he even jams with them.”

“Hmm,” I said. “Not sure if that’s my, you know, scene.”

“Oh, it’ll be fun,” she said. “You’ll see. And it’ll give you a break from pining over that comic book nerd.”

I dyed my hair black in anticipation of the big night, then spent the next couple of weeks laying as low as possible, waiting for the stains to wash off. I almost looked the part. Then, just before I was due to make my debut as a metal chick, the news came that a boy from the school across the street from ours had killed himself.

People were talking about it everywhere, including during the Sunday morning coffee klatsch at my grandmother’s, when the neighbors came calling.

“It was the drugs,” said sixth-floor Hiyam. “The marijuana.”

“It was all that ‘rock’ music he listened to,” said fourth-floor Youmna. You could actually hear the quotation marks in her voice. “That music tells people to do drugs if you play it backwards.”

“We never had any trouble with our young people before that American rock music arrived,” said third-floor Ghida, whose son had recently graduated from militiaman to minor politician, and who lorded her consequent rise in status over everyone.

“Devil-worshippers,” snorted my grandmother with contempt. “They always get what they deserve.”

“It’s all bullshit,” said Michael, later. “It was an accident. I know some of the people who were with him that day. They were having some beers by the sea. He was trying to show off, do this crazy dive, but he misjudged the depth. Leapt off the cliff and hit his head on a rock, broke his neck. I don’t know why everyone’s saying he killed himself.”

In the end, the details didn’t really matter; whatever it was that had happened, the Devil was to blame. I never did get to see him at American Dream. Shortly after the controversy, he blew out of town as fast and soundlessly as he had come. I imagined him on the bus to Damascus, biting his nails and looking out to sea. He’d only meant to have some fun, play a few pranks, seduce a few girls. He never imagined people would take him so seriously, not in Beirut.

I thought I spotted him during my semester at university in Canada, sitting up front in the Milton seminar.

He was older and had gothed-up his look somewhat, but the dimples were unmistakable.

“Who’s that?” I whispered to the girl sitting next to me.

“Some asshole,” she replied. “He’s bad news, always strung out on something. Thinks he’s a goddamn poet.”

Later, in her dorm room, she lit an incense cone, drew a pentagram with some chalk on the floor, and took my hand. “Chant with me,” she said. “It’s Samhain.”

“Is this like some kind of devil-worship?” I asked excitedly.

“Jesus, no,” she said, looking disgusted. “It’s Wicca. Man, patriarchy sure has done a number on your brain.”

After graduation, I got a job in an advertising agency in Beirut. When people asked me what I did, I told them I worked for the Devil. I felt bad taking his name in vain like that, because he’d seemed so nice in a bad-boy kind of way. I hoped wherever he was, he was trying to be happy, or at least working through all the guilt. I was big on working through guilt at the time, probably because I was working in advertising. One day, without any warning, he came back to town. This time they discussed his presence on talk shows, on the news. He’d decided to make some sort of comeback, apparently. His name was on everybody’s lips; everyone claimed to have spotted him somewhere. I was disappointed. How like a former rebel to sell out. I’d expected better of him.

For a while, he was all my colleagues could talk about.

“I don’t let my son go to the movies alone anymore,” one of them said. “There’s devil-worshippers everywhere.”

“You know they summon him at night in graveyards?” said another. “They have orgies, and then they sacrifice children. They cut fetuses out of women!”

“That fucking hack,” I muttered. “He’s cannibalizing his own work.”

They tsk-tsked their throats dry while I finished my sandwich. I tried to avoid the kitchen at mealtimes after that.

A while later the government got involved. They raided a few nightclubs on Saturday nights, lining up drunken revelers and making them turn out their pockets and hand over their IDs, herding them like cattle into the backs of armored vans. Over-zealous volunteers handed out leaflets on street corners with a bizarre mishmash of advice, information, and warnings about Satanists. A friend of mine was arrested for a passing resemblance to the Devil; it’s true they wore their hair in the same way, shoulder-length and tied back, but that’s really where the likeness ended. He wound up missing a job interview and wasn’t given another appointment — no self-respecting company wanted to hire a suspected devil-worshipper. During those two months, the police also busted into people’s houses and proudly announced on television how they were keeping the peace, keeping Beirut the safe place we’d all grown used to since the end of the long-ago war.

It was in the midst of that furor that I saw him last. I was dropping a friend off at the airport, and there he was, in the departure line. When they asked to search his bag, he was polite and deferential, but there was an air of disinterest about him. All the fire seemed to have gone out of his eyes. I regretted having disparaged him. It was no wonder he’d been repeating himself; he wasn’t so much a hack as a person uninspired. Once again, it seemed, Beirut had let him down.

It must have been only a few months later that a massive explosion shook the windows of the office and sent us all scurrying to our houses until the country figured out what the hell was going on. In the midst of all the tumult, no one once thought to blame the Devil. It was like he’d never come.

He hasn’t been back since, but the new checkpoints seem like they’re here to stay. None of the armed boys who check my papers and search my bags have even an ounce of his charm. Last month as I bent down to collect spent rifle shells from in front of my building,

I thought about the Devil and his grin, from those days long ago, when we were both younger and stronger.

I miss him. He was one of the good guys — just a little misunderstood.

Ubbad Al-Shaitan (Worshipping Satan)

RECENTLY

Devil worship recently cropped up in Europe and the United States. Founded by the Jewish Israeli American, Anton LaVey, who established the Church of Satan in San Francisco, he authored “the Satanic Bible,” considered by many to be the constitutional reference of devil worshippers. Their holy book, the Black Bible, is printed in Israel.

Israel is considered the primary source for this group, as it supported and propagated these sects inside the United States and some Arab countries, namely Egypt in 1996, Jordan in 2001 and Lebanon in 1993.

This religion is considered the high-fashion of the nineties, as Existentialism was in the Fifties and the Hippies of the Sixties and Seventies. The involvement of the Israeli Secret Service (the Mossad) has been repeatedly linked to the spread of these beliefs in many countries, causing widespread panic due to their queer and maniacal behaviour.

RITUALS

Their parties begin with loud, raucous Black Metallic music, which is purported to induce a psychological state which can weed out the strong, ambitious types with strong imaginations, musical abilities and an intellect close to Satan and the diabolical.

When the music gets louder, the members of the cabal begin taking drugs, stripping (a symbol of the breaking away of shackles) and when the dancing reaches its fervour they practice unsafe, group sex and faggotry, many men ganging up on a male or female participant, and all natural order is lost.

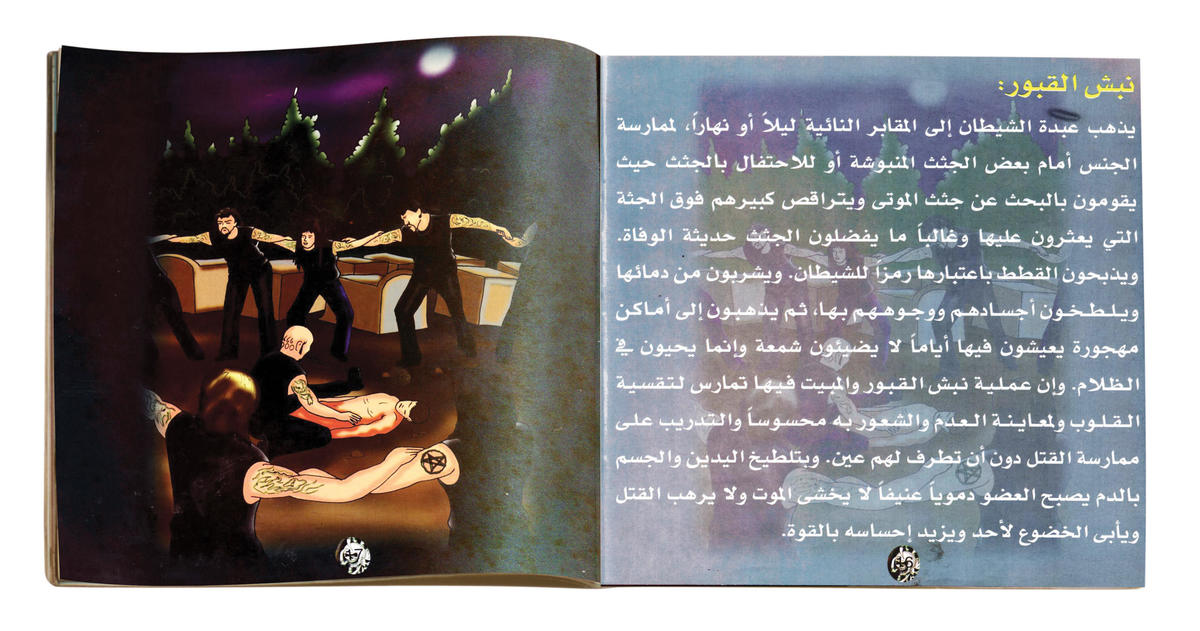

GRAVE DIGGING

Devil worshippers visit rural graveyards by night or day to have sex in front of unearthed bodies or to perform necrophilia. They find freshly interred bodies and their elders dance before them sacrificing cats which are considered the wards of Satan. They drink blood and smear it all over their bodies and faces before moving to abandoned places where they spend days alone in the dark, without even lighting a candle. The act of digging up corpses toughens the heart and brings one tangibly close to nihilism where he can learn to kill without batting an eyelash. By smearing blood all over the hands and body the devil worshipper turns rabid and violent, without fear of death or murder and slave to no one but power.

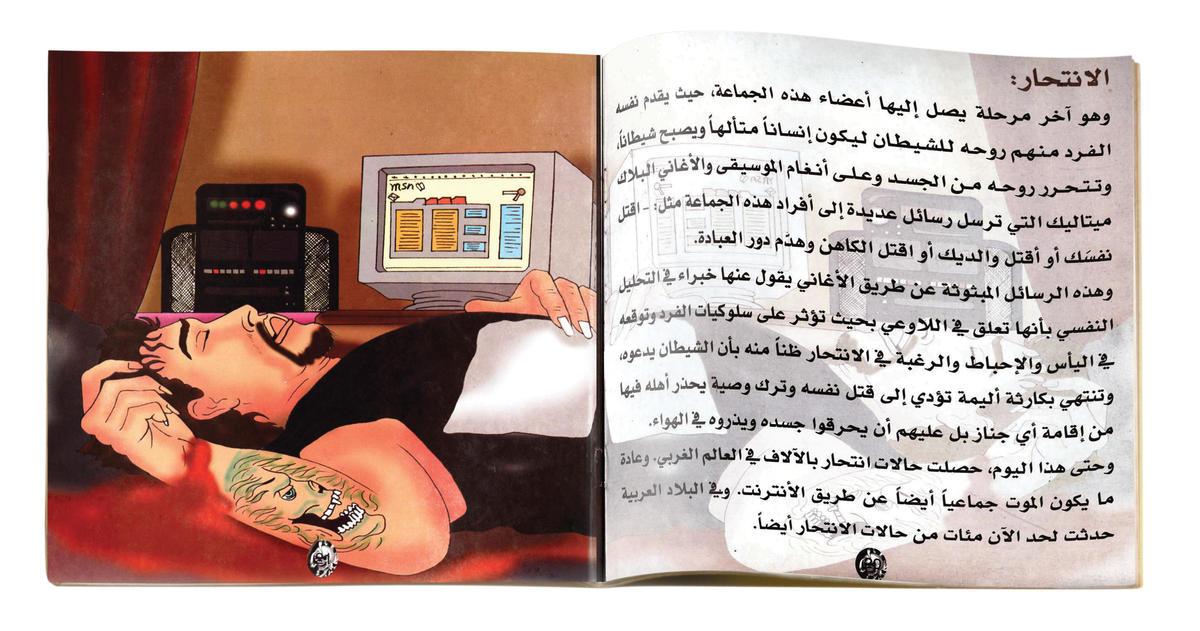

SUICIDE

And that is the final stage a member of the cabal can attain, whence they offer their soul to Satan so that he may turn them into demons. They release their souls from their bodies to the tunes of the Black Metallic which transmits subliminal messages to its listeners like: kill yourself, kill your parents, kill the priest and destroy holy places.

These subliminal messages have been analyzed by experts and proven to get stuck in the subconscious, where they alter behaviour, leading to depression and suicide. Believing that the devil himself is calling, the individual commits suicide leaving a note to his family forbidding any kind of burial and preferring to be cremated and released into the air in the form of black ash.

Thousands of similar suicides have been reported in the West, where the act is committed en masse through the internet. The same is happening now in Arab countries, with cases numbering in the hundreds.