Once upon a time in America, rock music was dangerous, subversive — revolutionary, even. For the aspiring rocker, that fairytale has had a sad ending — whatever promise or menace might once have attached to words like alternative, independent, or underground have melted into air. Whatever else contemporary rock music might be, dangerous it is not.

Except, of course, if you happen to be an aspiring rocker in the Islamic Republic of Iran, after the president of your country effectively makes it a crime to play rock music at all.

So perhaps it was not just the timeliness of Hypernova’s touchdown on American shores that set off a media frenzy in April 2007. American–Iranian relations were at an especially low ebb, and four fresh-faced (if swarthy) young men from Tehran were a perfect foil for saber-rattling Fox newsmen and other media sensationalists. ABC News called them “Iran’s Latest Ambassadors” — ambassadors from a land where loving rock and roll might get you fined or flogged or even jailed.

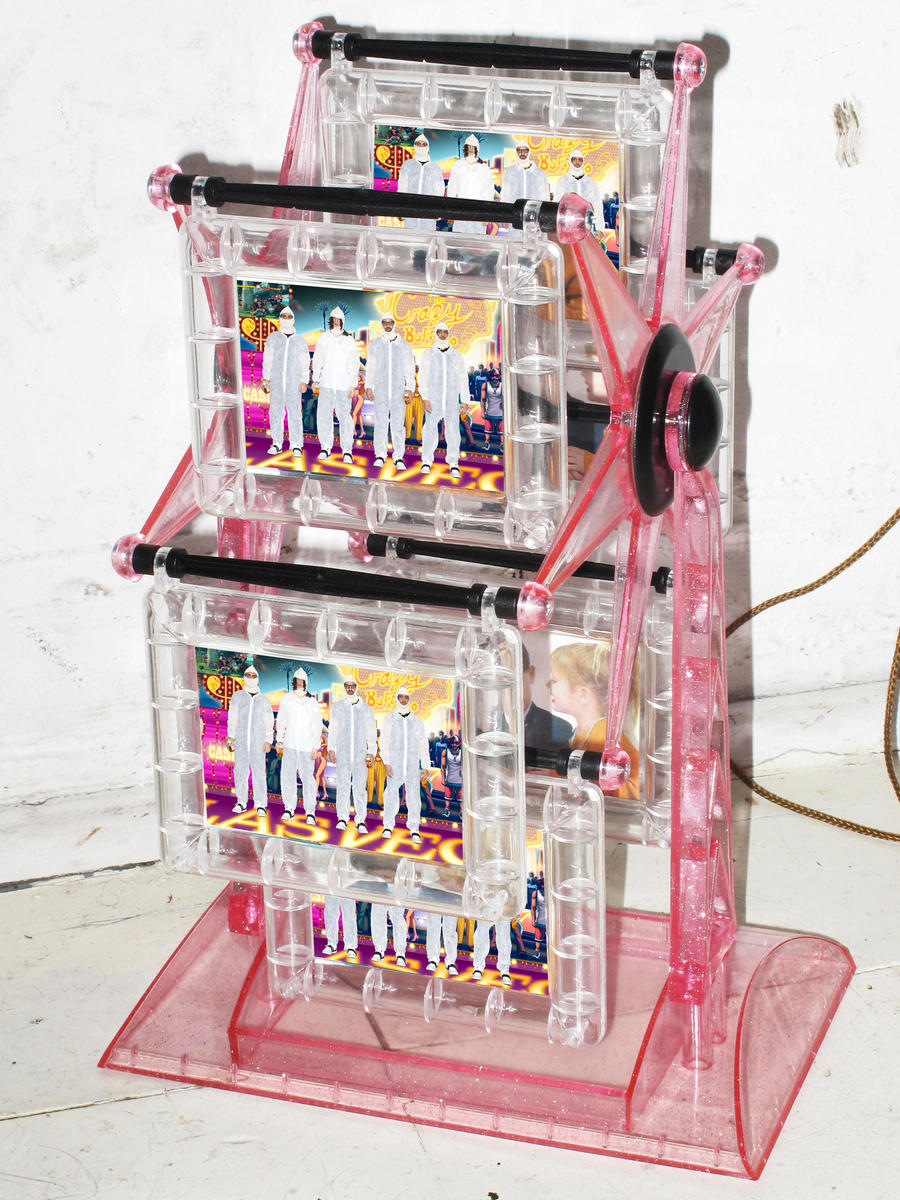

Hypernova are back in the news with the release of their debut CD, Through the Chaos. They’re signed to Narnack Records, a label that also features old-school heavies like Lee “Scratch” Perry and The Slits. And they’re featured, indirectly, in Bahman Ghobadi’s film No One Knows about Persian Cats. Last summer, they toured the US supporting aging gothsters Sisters of Mercy; this summer, they’re at or near the top of the bill themselves.

Not long ago, after seeing them perform live at the 92nd Street Y in New York, we invited them down to our headquarters, where the Iranian members of our staff discussed with them the ins and outs of Persian pop, the perils of publicity, and why Pink Floyd is still the biggest thing in Iran since Milan Kundera.

Negar Azimi: How do you feel about being marketed as an Iranian band?

Raam: It’s funny, I just sent an email to our manager today saying we wanted to stop being introduced as an Iranian band… . I think we’ve been very fortunate. We get so much attention just because of where we’re from, which is probably unfair to a lot of other bands who work just as hard as us but don’t get a chance to be heard. But we did go through a lot of hard times back in Iran, getting to where we are. I mean, obviously the story is really interesting to people who aren’t familiar with what’s going on in the underground scene back home. It has this sort of exotic, Oriental feel to it. But at the end of the day, we want our music to speak for itself. We want to have fans of our music, not our story.

NA: We were curious in part because of No One Knows about Persian Cats, that movie about the Iranian rock scene that was ostensibly based on a lot of research. They talked to you guys, right? Do you think the film will have an effect?

Raam: Obviously, the movie gave exposure to a lot of artists, and there are so many talented musicians in the underground scene in Iran. There are many who really aren’t talented or amazing, too — whether or not they deserve to be heard is for other people to decide. But I think you could almost say this movie was the death of the underground. Of this underground, at least. People are on the radar now like never before. The authorities and the government are aware that this is happening; they’re closing things down.

NA: Can you tell us more about that scene, the one that seems to be ending now? The late ’90s scene, when you guys came together, during the Khatami years. Were you collaborating with people, or was it isolated?

Raam: It was very isolated at first, simply because you were in, like, basements. One of the big things was the underground music festival that Tehran Avenue held in 2000. That was the first time anyone in Iran had heard all these bands at the same time. We were all really impressed. Everybody shared that belief, “There’s no punk band, there’s no metal band, we’re the only ones.” We all thought we were the only band in the country.

Kodi: I was too young to even be in that scene, so when I heard all those bands, I was like, “We actually have underground bands!?”

NA: How did they set it up? Did Tehran Avenue put on a big concert?

Raam: It was an online competition, everyone submitted tracks. One of the really great bands I heard for the first time then was this band from Bandar Abbas, a port city in the south where I would never have imagined anything cool happening. I was surprised, pleasantly surprised. After that, websites started going up. I remember on Yahoo! Messenger there were these chat rooms, and we’d have meetings. People would meet up in the parks and trade mixtapes and talk about who’s the fastest guitar player on the planet and dumb things like that.

NA: So what sort of things were you guys talking about? What were you into? Who are your “Western influences”?

Kami: I mean, we grew up listening to garage and alternative.

Kodi: Grunge, punk, alternative music.

Raam: I remember my first cassette was a Queen tape. A lot of Pink Floyd, obviously. I was a huge fan, and I still am.

NA: Why is Pink Floyd so big in Iran?

Raam: Pink Floyd is so big. And Dire Straits, they’re huge in Iran.

NA: Dire Straits?

Raam: I have this stupid theory that someone came to Iran in, like, 1985, with a box full of cassette tapes. And that tape collection was all we had until satellite TV came. I think it’s as simple as that. Then the Internet came along, and suddenly we were up to date with the rest of the world.

I mean, all that you ever heard on the radio was all this poppy Iranian music from L.A., in our homes and on the way to school. We were just sick and tired of it.

Now that I’m here in America, whenever I hear traditional Iranian music, I get all nostalgic… I think of the mountains…

Tiffany Malakooti: Like Toofan?

Kodi: You’d better not say anything bad about Toofan — he’s our friend’s uncle! [Laughter]

TM: I am Toofan’s biggest fan…

Babak Radboy: You were talking about how the scene wouldn’t be the same anymore in Iran, because of the movie. Do you regret, at all, the movie coming out, more people starting bands?

Raam: No regrets. Anyway, there are still really cool underground things happening, that are still pure.

Honestly, there’s only so far we could have gone in the underground in Iran. Back at home, people would always ask me, “What do you do for a living?” We’d be like, “Oh, we’re musicians.” “No, what do you do for a living?” I’m like, “I don’t do anything, I just make music.” In our traditional culture, it’s sort of a taboo to try and be a rock star.

TM: Wait, so what did you guys do for a living?

Kodi: The only one that actually had a real job was

Kami:. I was still in school with high hopes for my university education. [Laughter]

Raam: I made him drop out of school to join the band.

TM: Do you have a fake ID?

Kodi: Uh, I do, but it’s actually my brother’s. I don’t get to use it much anymore, because people at bars know us, so they sneak us in the back door.

TM: And what did you do when you were in Iran?

Kami: I worked for eight years in an industry job, heating and cooling systems for buildings, factories.

BR: Heavy.

Raam: Kami was a hard worker back in Iran. The rest of us were a bunch of lazy bums. I would do a lot of outdoor stuff — I would always be in the mountains camping. It was just the best getaway from all the madness in the city. I would just go out to the mountains and get high and drink and just do crazy shit and have fun. That’s one of the things I miss about Iran. I used to go to the desert.

NA: You made the decision to apply for a visa. Were you conscious of what you were giving up?

Raam: To be honest, I swear to God, when we came to the States, there was no Plan B. We didn’t even say proper goodbyes — we didn’t even know what we were getting ourselves into. We had no idea. And people think that we had this whole thing planned out to move to the United States — we came here with one suitcase and a guitar, literally, and a couple hundred dollars each, and we had round-trip tickets. We didn’t know anyone in the States, we didn’t have a place to stay, we didn’t know how the music industry worked. We just threw ourselves into this unknown universe and let the chips fall where they may. One thing led to another, and suddenly our parents were calling us and saying, “Why aren’t you coming back home?” [Laughter] And it just seemed like we were onto something. So we decided to ride it out.

There were two features, one on MTV and one in the New York Times, that really got us a lot of attention. When they came out there were, like, a thousand emails in my inbox, people from around the planet telling us how inspired they were by this story of ours. We were all just overwhelmed. Anderson Cooper wanted me on his show, they wanted me on Fox News, Good Morning America — they wanted us to do all these crazy things, and we just didn’t feel comfortable.

BR: What kinds of things?

Raam: We sort of knew where we were as musicians, you know? And we knew that we were not ready to perform live on national TV. Our first goal in the States was just to develop our sound. Back in Iran, all of our equipment was really crappy, and you never had proper rehearsal space, proper equipment. We couldn’t play our music the way that we wanted to, the way we heard it in our heads.

BR: Did you get the sense that you were being used to tell another story? To the Fox Newses of the world, for example?

Raam: We’ve done a couple of Fox News interviews, believe it or not. In the beginning, obviously, we were a human interest story. Right when we arrived, there were those British hostages taken in the Persian Gulf, so there were headlines like “British Hostages Taken” and “Underground Band Rocks Ayatollahs.” They used all these catchy headlines, and they would take all my words out of context. And people were emailing me, “What the hell are you saying about Iran?” I realized then how hard it is to do interviews. One of the hardest things I’ve learned in this journey is that I can’t make everyone happy. After every single interview, I get a shitload of hate mail. It’s just how it goes.

TM: Who sends you hate mail?

Raam: Sometimes it’s Americans telling us to go back to Iran. But actually a lot of it is from Iranians. They’re so proud about everything, you know? The smallest thing that we say, they just go all crazy about it. It’s funny — we try to stay away from Iranian media.

NA: In America, you mean?

Raam: We just did one Iranian radio station in Los Angeles. We made fun of Iranian pop musicians, and all of a sudden the phone went off the hook. All this, “Who are you bastards?” But you know, we don’t care, we hate that style of music, that sound. I don’t care what people like. We’re against it. I don’t care what people think.

One of the funniest questions I always get is, “What do you think about the nuclear standoff between Iran and the US?” I’m like, “What the fuck do you want me to say?” People are always trying to make us into some kind of political band. But we’re not Rage Against the Machine.

NA: Do you ever feel you’re being used? Like, that people want you to tell them what they think they already know, confirm every cliché about “life behind the veil”?

Raam: Oh, all the time. I mean, it’s true that everything we did in Iran was illegal. What we did was very dangerous. But at the same time, life isn’t as hard as Fox News imagines. You get used to living with your fear — because it’s true, fear is something you grow up with in Iran, you’re constantly bombarded with threats, and there’s always this sense that you can’t trust anyone. But after awhile, you get to a point where fear doesn’t even play a role in your life anymore. You don’t care if you’re going to get lashed or thrown into jail. You just want to play your music. And that’s where it became easy, actually. Once you don’t care anymore, life becomes pretty easy.

NA: Were you guys surprised by what happened in Iran last summer? I was totally surprised. I’ve spent a lot of time there, and I didn’t think the Iranians had it in them. It always seemed to me that people didn’t feel like having another revolution.

Raam: I wasn’t surprised at all, actually. People just reached a tipping point where they felt like they had nothing to lose. They were willing to sacrifice everything, especially for a great cause. I think the people really have had enough. The younger generation is becoming disconnected with this sort of archaic government. I think it’s only a matter of time before the people’s cause will prevail. I really do.

NA: What was it like for you guys, experiencing what happened from the States?

Raam: It was so hard — we had one of our biggest shows, one of the coolest shows of our lives, the El Rey Theatre in Los Angeles, a sold-out show. It was the second night, when we started seeing all the brutal images. It was hard for me to sing that night. We were all very emotional. I was in such a sad state of mind.

Kami: We were 24/7 on YouTube, looking for videos to see what was going on in Iran.

Raam: We couldn’t get off our computers. I was just Twittering, Facebooking, sharing information. Trying to help, to be active somehow. But at the end of the day, it’s up to the people over there to decide their own fate.

NA: Can you trace this back to the election of Ahmadinejad in 2005? Was that a big deal for you?

Raam: During Khatami’s presidency, the reforms were happening, and we saw firsthand how much more freedom we were experiencing, getting together in parks or partying or whatever. Everything felt a lot more comfortable, and the authorities were a lot easier on the kids. There were certain ugly instances under Khatami, of course, but generally it was a much more positive environment.

Under Ahmadinejad, things started slipping away. One of the first things we noticed was the tariffs going up on musical instruments. That was a very subversive way of combating Western music. A guitar that costs $100 here would cost $800 in Iran. The idea was to make it so that kids couldn’t afford to buy instruments. I mean, that’s what I think happened.

BR: It’s funny. The idea of rock ’n’ roll as something illegal — that’s like a dream for a lot of people here in the States, you know?

Raam: The best show we ever played was in Kashan. It was an illegal concert where we forged documents from the Ministry of Culture. Kashan is very religious — after Qom, it’s the most conservative city in Iran. And I’m a very paranoid person. No one told me that the local Basij had raided the place the week before and beat up everyone in the hall. And they weren’t even playing rock music! If I had known that, I would have cancelled the whole thing. The kids at the university forged documents saying that they had permission to hold the concert. So there’s all these forged documents, and we go to the show, and there are, like, 450 people in this big amphitheater, and they’re all sitting down, and there are all these undercover police in the audience with their walkie-talkies. And as we played, there was this big picture of Khomeini on one side and one of Khamenei on the other. And we’re rocking in the middle.

Kami: And the sign said “Music for Peace.” We covered a Franz Ferdinand song.

Raam: We had so much fun. And we barely got away with it. Suddenly, as we were leaving the building, the authorities were onto us — like, “What did you guys just do?” A friend of ours distracted them, and we got away. We were really lucky. And the feedback from the kids was so powerful. I don’t think anyone has ever clapped for us the way they did at that show — everyone in that room understood the importance of what was happening. And they appreciated every second, even though, I mean, we sucked musically.

Even just organizing these shows was exciting. Where do we load in, how do we load up, what time do we go, who’s our lookout? We have lookouts on the streets that call us if the police are there. How much money do we put aside to bribe the police?

And then, how will we deal with the sound? Kami would bring foam, and we would put mattresses against the wall, blankets, anything, so the sound wouldn’t get out. It was such a rush! Knowing that at any second everything could be ruined. I have yet to feel that adrenaline here in the States. That feeling, where everybody has everything on the line, is such a unique experience. I don’t think we’ll ever be able to have that sort of experience again.

NA: You mentioned hip-hop being so popular now. I’ve always thought of heavy metal as a sort of defining music in Iran. Is that still a big deal? I mean, do you guys listen to metal?

Kodi: Metal is definitely huge in Iran, but unfortunately Iranian metal bands suck really hard. Whether they’re singing in English or Farsi, there’s no way of relating to them. Whereas with hip-hop, part of why it’s huge is because it’s in Farsi. Hip-hop is a medium for people to communicate their frustrations — and Farsi is a very poetic language, as you know. I think that’s why it goes so well with hip-hop, how they transfer this feeling through the music. It’s very powerful.

BR: Did you sing in English in Iran, too?

Raam: Yeah. We tried singing in Farsi, actually, but English just suits our style of music better. I mean, I actually grew up in the States. I was born in Iran, but I grew up in Oregon. That’s why I became a singer. When I first moved back to Iran, Kami and I wanted to start a band. He played drums, and I had a friend who played guitar. Kami asked me if I played an instrument. I didn’t, so he was like, “Well, you speak English, so you’ll be our singer.” That was it. I was the singer, not because I had a good voice — my voice was awful — but I could write better lyrics in English than Farsi, at the time.

Kami: It was like a dream to find someone in Iran who sang proper English, you know.

BR: If you could go back to Iran and play there, would you?

Raam: Oh, I’d do it in a heartbeat.

BR: Would you guys rather be based there? If it wasn’t, you know…

Raam: For me it doesn’t really matter where I’m based, because I want to be just on tour all the time, around the world. We don’t want to be based in New York — we just want to be on an airplane, basically.

I can’t wait till we do a national tour. One of the best things about touring is that in every city we visit, we find the weirdest, creepiest, Lynchian-type people, and we party with them. Everywhere we go. It’s so cool going out and seeing this. There’s so much happening in America.

BR: Have you noticed a type among your fans?

Kodi: The goth crowd, uh, tends to…

Raam: The goth crowd likes us a lot, apparently.

NA: Do you think it’s your hair color?

Raam: I think it’s because we sound kind of like Bauhaus. And we dig that sound ourselves, too. But we’re a little different.

BR: Are there goths in Iran?

Raam: Not really.

BR: Shia is so goth.

Raam: Yeah, it’s like self-inflicting pain and all that.

BR: No one would even notice if you were goth.

Raam: You’re right, you could totally pull off being a goth.

TM: Undercover goth. [Laughter]