Kassel

Documenta 12

Aue-Pavillon

July 16–September 23, 2007

When Roger M Buergel, the artistic director of Documenta 12, first released the three leitmotifs in February 2006 that would “correspond, overlap, or disintegrate — like a musical score” in the exhibition, I was struck with wonder. “Is modernity our antiquity?” “What is bare life?” “What is to be done [with education]?” These questions seemed provocatively elusive, strangely scattered, and perhaps just a bit too (academically) trendy. When he and the curator of the exhibition, Ruth Noack, failed to release the hotly anticipated list of Documenta artists — a list that functions more for marketing and social-climbing than anything else — I was even more intrigued. And in January of this year, when Buergel participated in a New Museum “Hot Button!” panel at Cooper Union and delivered an impromptu meditation on, among other things, a photo of the shipping containers used as “Art Positions” galleries at Art Basel Miami (“an allegory of an aesthetic of death”), I was in love.

While walking through the exhibition, my high hopes shifted into mixed reactions: dissatisfaction flipping into infatuation; awe that quickly wore thin and then ballooned into tears; and, in the aftermath, heated arguments about why it’s “good” that the fantasy of building a Crystal Palace to house the curatorial paradigm of the twenty-first century ended up as such an ostentatious aberration. Yes, I even thought the screwed-up engineering that allowed this summer’s climate-change torrential storms to seep water into the Aue-Pavillon added to an aesthetic of disarticulation. And when Ai Weiwei’s neo-imperial “Template,” a twelve-meter-high temple of wooden windows and doors salvaged from “all over China,” was knocked down by strong winds, even better. What, you might ask, could possibly be so interesting about one of the most important international art exhibitions in the former West becoming such a mess?

In some ways, Documenta 12 was an attempt to revisit the improvisatory spirit of Documenta before it became such a major institution. Originally enacted in tandem with the German Federal Garden Show of 1955, the “first” Documenta (whose organizers were unaware of its position as the first of many) was meant to serve multiple postwar governmental and cultural aims, from pragmatically redirecting tourism to the marginalized, war-torn city of Kassel to emblematizing the potential for the recovery of a shattered civilization. Literally, roses grew out of piles of rubble, and art was displayed in the “scantily renovated” ruins of the Enlightenment-era Museum Fridericianum. It goes without saying that much has happened since 1955, but Documenta 12 pulled from the original a Shubertian sensibility, the melancholy beauty of high hopes in the void. Documenta 11 (2002), whose thematics gained electrifying legitimacy as fatigued academic discourses shifted into popular overdrive post–September 11, was a massive and sometimes tiresome overview of art and architecture related to the curatorial team’s ideas about globalization. Documenta 12, on the other hand, found its five-year cycle smack in the middle of the current global situation: the banality of apocalypse. Rather than attempting to give an overview of responses, or preaching about current events, Buergel and Noack took the more old-school position of curator-as-dilettante-nerd — in the sexiest sense of that accusation. They tried out too many ideas, mostly only halfway; they tracked down obscure, rarified artists and decorative objects, many previously “unknown in the West”; they used the site for experiments in weirdness, digression, fantasy, and play; and they gave the proceedings a quaintly retro, early nineties sense of sexual transgression. But what could it mean to recover the subjectivity of an intellectual upper class after so many challenges to and reconfigurations of the notion of curator as wayward aristocrat?

Noack and Buergel — but especially Buergel — can be accused of flinging out some pretty bizarre provocations. (When asked in a German news conference about the perceived failure of the “Crystal Palace,” Buergel responded that “in order to raise money, I endorsed it as a Crystal Palace. Now it’s a favela.”) But whatever can be said about their public statements and sometimes flippant treatment of individual artists included in the exhibition (complaints on this front circulated wildly in the art world), I found the curating to be radically lyrical — with a particular generosity to openness in the spectator’s imagination. This went against the grain of the now orthodox practice of treating artworks, particularly “political” artworks, as having meaning or meanings determined by various contexts, with the explanation of these contexts determining what connections are made and what is “learned” by the spectator. What was strikingly new about Documenta 12 was that a no-explanations-needed, “high” art curatorial approach — one that usually aligns with a more conservative idealist aesthetic of beauty or speculative aesthetic of marketing — met a taste for third world, sociological, queer, Eastern, diasporic, feminist, and other disruptive aesthetics. Indeed, the most political aspect of this show lay not in giving visibility to outsiders, as some have argued, but in an arrangement of artworks that caused spectators to confront and question multiple, perhaps previously unrecognized, subjectivities as complex, artistic, and politically implicated.

It’s not that there weren’t aspects of the exhibition design and individual artworks that I didn’t like; but not liking became an additional element in a complex blend of emotions, sensations, passing thoughts, and reconsiderations. In “best of” survey exhibitions, I often feel like I’m flipping channels between individual art careers, forgetting one as soon as I pass to the next; with Documenta 12, it was passages, mazes, gardens, back alleys — intense encounters mixed with a detailed accumulation of memory. Emblematic of this was a passage of artworks inserted in a sort of void space behind an exhibition of Dutch paintings, Of the Aristocracy of Painting: Holland Around 1700, on view in the Old Masters Portrait Gallery of the Schloss Wilhelmshöhe. I made my way through.

Where is the Documenta part? Oh, behind this wall — a video projection (Danica Dakic, “El Dorado,” 2006–2007). A black teenage boy, standing in a museum, speaks in piercing, broken English about some terrifying experience in the Frankfurt airport: strange rooms, a chasm of waiting, confounded non-communication. Another “ausländisch” teenager kickboxes with a bucolic wallpaper in the background. The story in voiceover starts to cohere: the dissociated experiential details of seeking asylum in Germany. Cut to the director of Kassel’s Wallpaper Museum, lecturing in crisp High German about a nineteenth century wallpaper called El Dorado: a panoramic view, from Africa to peacocks to South America, mixed with mosques, Chinoiserie, and tropical foliage — in the countryside of Europe? The boy’s voiceover starts again, while other teenagers do repetitive activities throughout the museum, one running in place, some performing less coherent movements: “Will try everything to reach my goal. Because now I am alone and I must work hard to survive. I must start a new life. Yes, a new life. Life doesn’t stop.” It reminds me of late nineties Nike ads — but what could “just do it” mean to a refugee in Germany, where nationality is still defined predominantly by blood, and an entire life can be passed under the legal status of “guest”?

Another dark room with little spots of light illuminating individual artworks, like floating thoughts awaiting nexus. The blur of tears makes Mira Schendel’s notebooks look like diagrams of what happens to language and mathematical logic during acts of torture, during the “unmaking of the world” (Scarry) at the nucleus of “bare life.” What do you get when you add AE/, with a tiny arrow pointing into the E, + 000(wxyz), with an arrow pointing straight up like a comma between the x and y, hovering in warped, folded, shattered planes with similar marks and symbols reaching for descriptive clarity as the body receives another blow? An anonymous drawing from Calcutta (circa 1900) of a courtesan dressing her hair starts to reverberate Matisse, while in a sketch by John McCracken a cartoon bolt of lightning strikes one of his emptied, alien slabs; Hokusai’s drafts for the ornamentation of artisan craftswork start to prefigure minimalism — how does this recrumple the stories of the wrapping-paper dialogue between Imperial Japan and colonial Europe? Extraordinary Mogul Indian Miniatures from the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries by Haddschi Maqsud At-Tabrizi, Mihr Chand, and others left unidentified, rip apart the connecting seams: several museums are nested one inside the other, and these crystallizations of narrative, emblem, history — Persian calligraphy, Hindu iconography, Chinese styling — start throbbing.

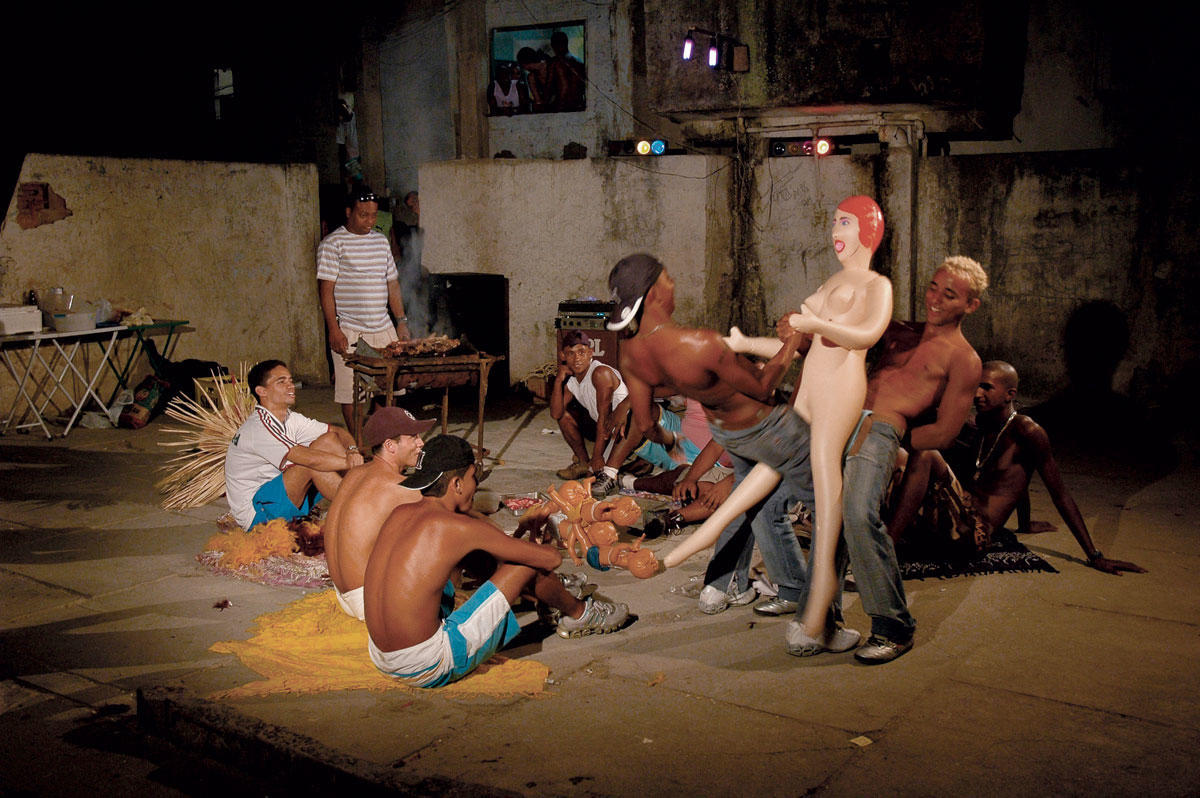

Through another passageway, a video projection — what the fuck is going on here? (Dias & Riedweg, “Funk Staden,” 2007) Big, sexy sausages on the grill, booty dancing, a circular array of camcorders atop a wooden rod spinning around by a bonfire, sixteenth-century colonialist illustrations of encounters with “wild cannibals” in Brazil, two sweaty guys humping a blow-up doll, funk music…

In this passage, the three leitmotifs of Documenta 12 incited a crisscrossing of formal, emotional and intellectual elements — and set the spectator’s self-reflexive imagination on fire. But it wasn’t simply an open-ended fantasia: what emerged as a ligature connecting the leitmotifs was a questioning of what to do with the concept of otherness that has grounded European paradigms of identity since New World encounters spawned the “noble savage” at the core of “know thyself.” This is not a new line of questioning, but one that seemed particularly relevant given recent reterritorializations of otherness as essential and functional. Documenta 12 suggested that there is a picture of reality more interesting than what is produced by a society coordinated by networks of “in” and “out” groups; to see that reality, however, demands dealing with the feeling of one’s smug, stable, Western self-losing coherence.