Dunepark (2009), a forthcoming project by the French artist Cyprien Gaillard, will take place in the Dutch coastal town of Scheveningen. The Netherlands, as Robert Smithson once wrote, is “an earth work in itself,” a nation- size readymade, formed from dams and artificial deltas, of land clawed from the sea. Dunepark, though, is concerned with a deposit of another type of territorial expansion. On an outcrop above the beach, Gaillard will excavate a WWII-era German military bunker, exposing its concrete mass to twenty-first-century eyes before returning it to the sands.

Courtesy of Laura Bartlett Gallery, London

In a way, Gaillard’s project recalls Smithson’s earth-heaped Partially Buried Woodshed (1970) at Kent State University, Ohio, the title of which can’t be beat as a description of its physical form. But while the American land artist’s work suggested a future in which nature would reclaim space from manmade structures, Dunepark is an archaeology of the proximate present, with its violence and its complicities, its checklist of things to forget. The bunker resembles (in stark contrast to the muscular, rather camp classicism of the Nazi architectural ideal) a modernist sculpture, and anticipates 1960s brutalism, although it is not a structure that was built with aesthetics in mind, but rather pertains to what Gaillard terms “the architecture of emergency.” Designed to withstand the bombs and machine-gun fire of the Allied forces, its form didn’t anticipate its peacetime repurposing — something that would amount, if similar bunkers on the British coast are anything to go by, to a place for teenagers to smoke joints and make their first exploratory forays into each other’s jeans. Abandoned after the war’s end, it has been slowly swallowed by the earth, as if the earth were a nation consuming its own painful, shaming past. Contemplating the bunker’s half-buried form, I got to thinking about Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem “Ozymandias” (1818), in which he relates a vision of a shattered statue of the pharaoh Ramses the Great, its inscription — “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!” — mocked by the “lone and level” desert that surrounds it. Sovereignty, even the sovereignty of tyrants, is in geological terms a fleeting thing. It tends toward entropy, just as Gaillard’s unearthed concrete mass will one day be reduced to sand.

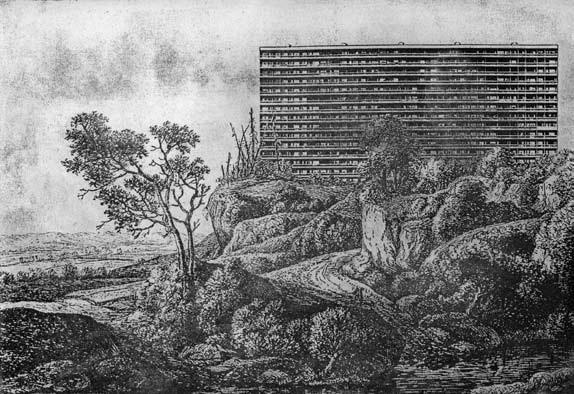

Dunepark might be thought of as a cousin to Gaillard’s recent Cenotaph to 12 Riverford Road, Pollokshaws, Glasgow (2008) — an obelisk cast from the remains of a Glaswegian modernist social housing project, demolished in advance of the city’s hosting of the 2014 Commonwealth Games. Placed within a wasteland-like “secret garden” in Hubert Bennett’s iconic brutalist Queen Elizabeth Hall (1967), London, the work, unlike Cleopatra’s Needle directly across the Thames, is half-hidden from the public, visible only through the internal windows of the concert hall’s foyer, or on an organized tour. Not a display of colonialist spoils, then, but rather something close to a resurrection or reincarnation. The word “cenotaph” betokens a monument to someone or something whose remains are elsewhere, and at first reading this seems an inappropriate designation for this obelisk — it is formed, after all, from the leavings of the building it memorializes. Perhaps, though, what is being remembered here is not the physical stuff of concrete, brick, and glass, but rather a devalued history, and a devalued dream. The fortress walls of the Queen Elizabeth Hall afford Cenotaph a level of protection uncommon to works of public sculpture. One chapter in the history of modernist architecture enfolds another, and a second, half-secret life is eked out. Looking through the windows of the concert hall’s foyer, the casual visitor might imagine that Gaillard’s obelisk (with its trans-historical form) has stood in that space since long before the building’s birth.

Courtesy of Laura Bartlett Gallery, London

Gaillard has said that “No one wants monuments anymore,” and perhaps this is why his obelisk is half-hidden, and why Dunepark’s bunker will be returned to the earth. To view them, however briefly, is to be reminded not only of the past, but also of the past’s (sometimes welcome) frangibility. The ruin is not a matter of if, but only of when.