In Elisabeth Bumiller’s Condoleezza Rice: An American Life, there’s a grainy black and white photograph of the future United States secretary of state that reveals a person few knew existed. Rice is on an ice rink in Denver, Colorado, in the late 1960s. She wears a figure-skating outfit: a girlish white dress, tights dipped in glitter, the snug-fitting white leather lace-up Victorian boots that embody the sport’s campy elegance and dowdy glamour. She is held midwaltz by a prepossessing young white man dressed in black slacks and a cardigan, a sharp part in his hair and a curl, slick and flammable, plastered to his forehead. He looks comfortable, professional, while Lil’ Condi appears stiff and self-conscious, counting the moves in her head, legs and hips fused at the joints. Her mouth, parted slightly, reveals the signature gap in her teeth. She looks vulnerable, exposed — yet at the same time, her discomfort appears mixed with a thrilling, if uncertain, joy.

You look at this photograph, and you see the bliss and uncertainty, and you want to like Condoleezza Rice. You wonder, how did that young girl, oblivious to everything but the numbers of the routine and her closeness to that boy who was not her father, become a woman who was moved to tell Bumiller that she is “not an automaton,” whose friends search for the word “human” to describe her? How did those cheeks become so harrowed? And what of the quality suggested by the Italian phrase from which her name derives? Con dolcezza: with sweetness.

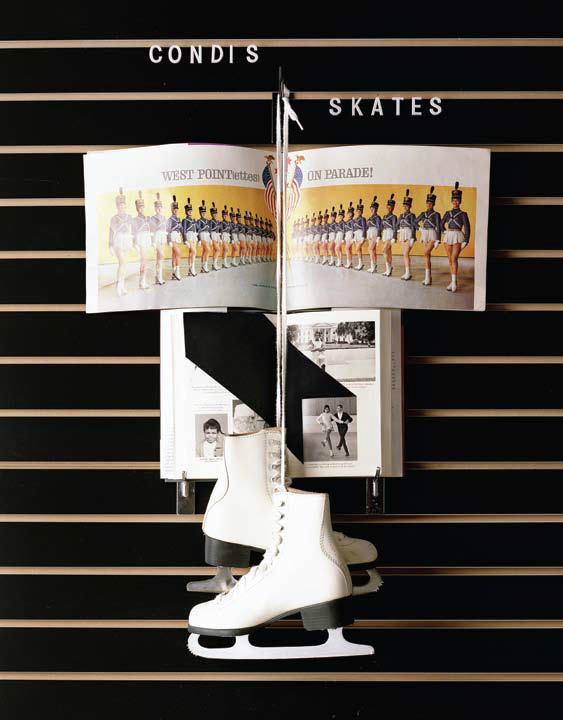

“I was terrible,” Rice states of her figure skating years, admitting failure for once. After six years of 4:30am wake-up calls, she realized that she couldn’t do it. She couldn’t bend her knees, she says. A judge once commented that it was amazing that she could do a double jump at all, since her feet never actually left the ice. But those skates would later assume a totemic power for the woman who would become George W. Bush’s muse and companion; she had not been swept up by the civil rights movement or “the counterculture,” she insisted, because all she did in those turbulent years was “play the piano and ice-skate.”

She had better luck with the piano. By age four, she was giving recitals, and as she grew older, her friends would hear her practicing Mozart and Beethoven before stickball games in the summertime. Rice was hailed as a prodigy, and not for the last time. She was recruited by Stanford University at twenty-six and tenured at thirty-one, one of the youngest full professors in that institution’s history, certainly the youngest black, the youngest woman. At thirty-eight she was provost. She was the first black person and the first woman to be national security advisor. In 2005, as she became the first black woman to serve as secretary of state, there was talk of yet another prodigious achievement on the horizon: the first black president, the first woman in the White House.

Alas, Condoleezza.

For all her storied achievements, there is a sense that what Condi Rice became was a well-heeled warning to prodigies everywhere. A walking catalog of firsts, Rice never quite distinguished herself in any of those positions. By her own account, she’s a mediocre pianist. At Stanford, she alienated faculty and staff while prompting ongoing lawsuits from the California Board of Labor. (“I don’t do committees,” she once said after a rash of firings, having learned essential lessons from her study of Stalin.) As national security advisor in the months before 9/11, she ignored the warnings of an imminent terrorist attack while greasing the wheels that led to war in Iraq.

Most of Bumiller’s biography is devoted to these more epic failures. But I can’t help wondering whether something was lost on the Denver ice, when her six-year career as a figure skater came crashing to an end and with it, perhaps, that certain sweetness. Gone forever, the utopian world of Austrian waltzes, Argentine tangos, and courtly love and romance; gone the Victorian costumes, the closeness of that boy who was not her father.

Alas, poor Condoleezza.

She was not the first black girl to pursue a career in the fairy-tale world of figure skating. That distinction belongs to Mabel Fairbanks, who bought a pair of used skates for a buck-fifty, stuffed the toes with cotton, and began practicing on frozen ponds in 1930s Harlem. Fairbanks wasn’t allowed to compete professionally, but she later became a coach and mentor to numerous young skaters, including Atoy Wilson, the first African American to win a national title (in 1966, about the time Rice’s photograph was taken), and she was the first African American inducted into the Figure Skating Hall of Fame.

Rice is the product of a particular kind of African-American upbringing, a hyperactive yet hermetic response to the brutal indignities of Jim Crow and the overt racial hostility of 1960s Birmingham, Alabama, where she lived until the age of thirteen. (A classmate was one of the four girls killed in the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in 1963.) Her fiercely independent father trained his daughter to be proud and self-reliant; yet he also disdained the civil rights movement and its “uneducated, misguided” leadership. She was to the manner bred, through years of elocution and etiquette lessons, French- and Spanish-language training, the piano and the ice skates and the Barbizon modeling courses, all of which contributed to her southern feminine wiles and her patrician manners — and, it seems, a lust for shoes that not even a hurricane could stop. She was trained to be an exceptional Negro, better than the other blacks and, more importantly, better than the whites — indeed, fuck the whites, whiter than the whites.

Alas, poor Condi.