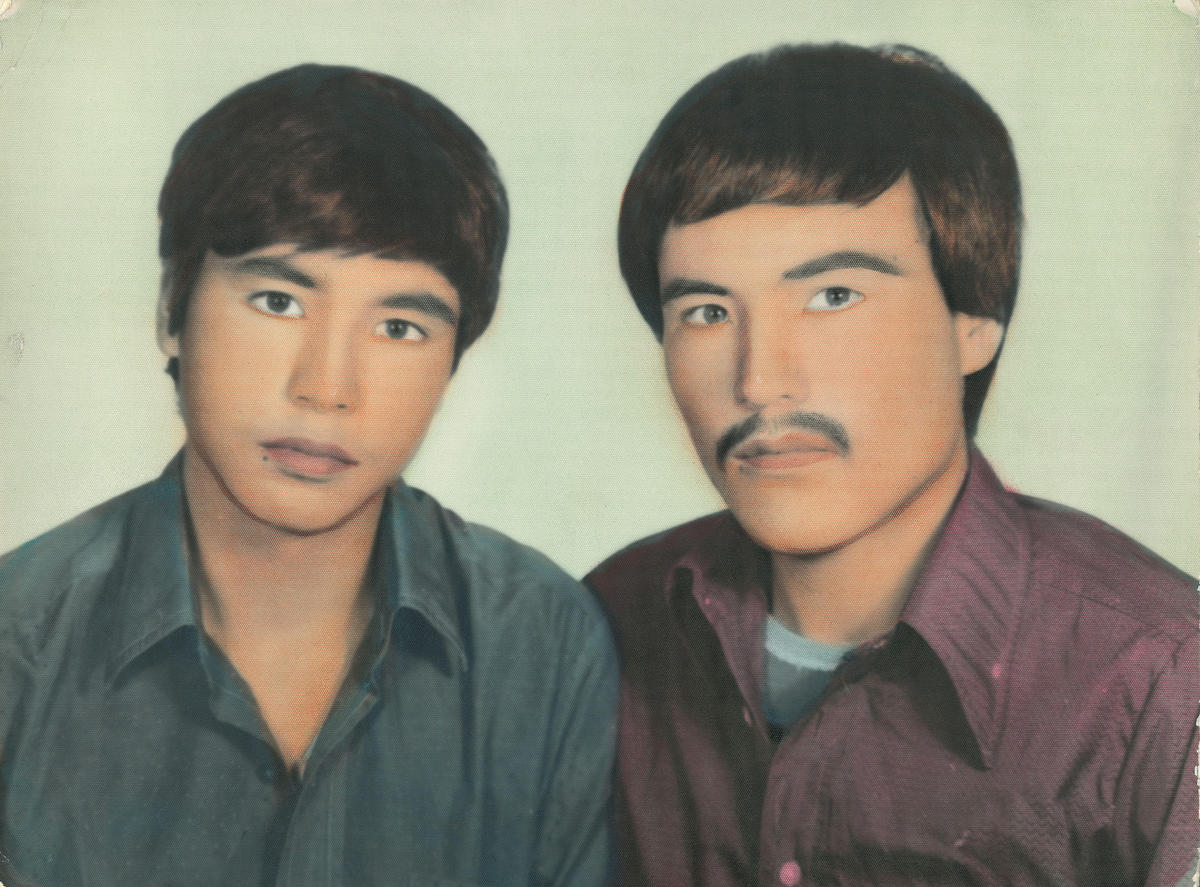

Thousands of gravestones extended into the distance. I walked over to one section and stumbled upon a curious sight. Photographs of young men, beautifully hand-colored studio portraits — probably from the 1970s given the gratuitous polyester — stood above each and every grave. Locked away in sterile plexiglass vitrines, the photographs gave each gravesite the aura of a shrine. A group of young men took turns posing for the camera at one grave, pictures with a picture, not unlike the kind of pilgrimages that mark the graves of fallen rock stars.

Later I learned that these young men posing for the camera were university students and the sought-after photograph in question depicted a young martyr — a sixteen-year-old casualty of Iran’s grueling war with neighboring Iraq in the 1980s. That young martyr is now lionized as a hero, his portrait found on murals, postage stamps, and trading cards throughout the country. His story, like so many others, has made its way into the historical folklore surrounding the birth of the Islamic Republic (see Hamid Dabashi and Peter Chelkoswki’s Staging a Revolution: The Art of Persuasion in the Islamic Republic [New York University Press, 1999]).

That day in Behesht Zahra cemetery was where my investigations into Iranian visual culture began. Most existing works on Iranian photographic history focus on the Qajar era, the ruling dynasty that extended between 1796 and 1925. Photography during this period entered the country by way of then-ruler Nasser-ed-Din Shah’s (1848–1896) introductory trip to Europe. Photographs from the era often reveal the mustached leader snapping self-portraits, clearly enamored of the possibilities afforded to him by his ability to capture his own image, that of his wives (harems), soldiers, and court. Photography at this time was still an aristocratic preoccupation reserved for the privileged few.

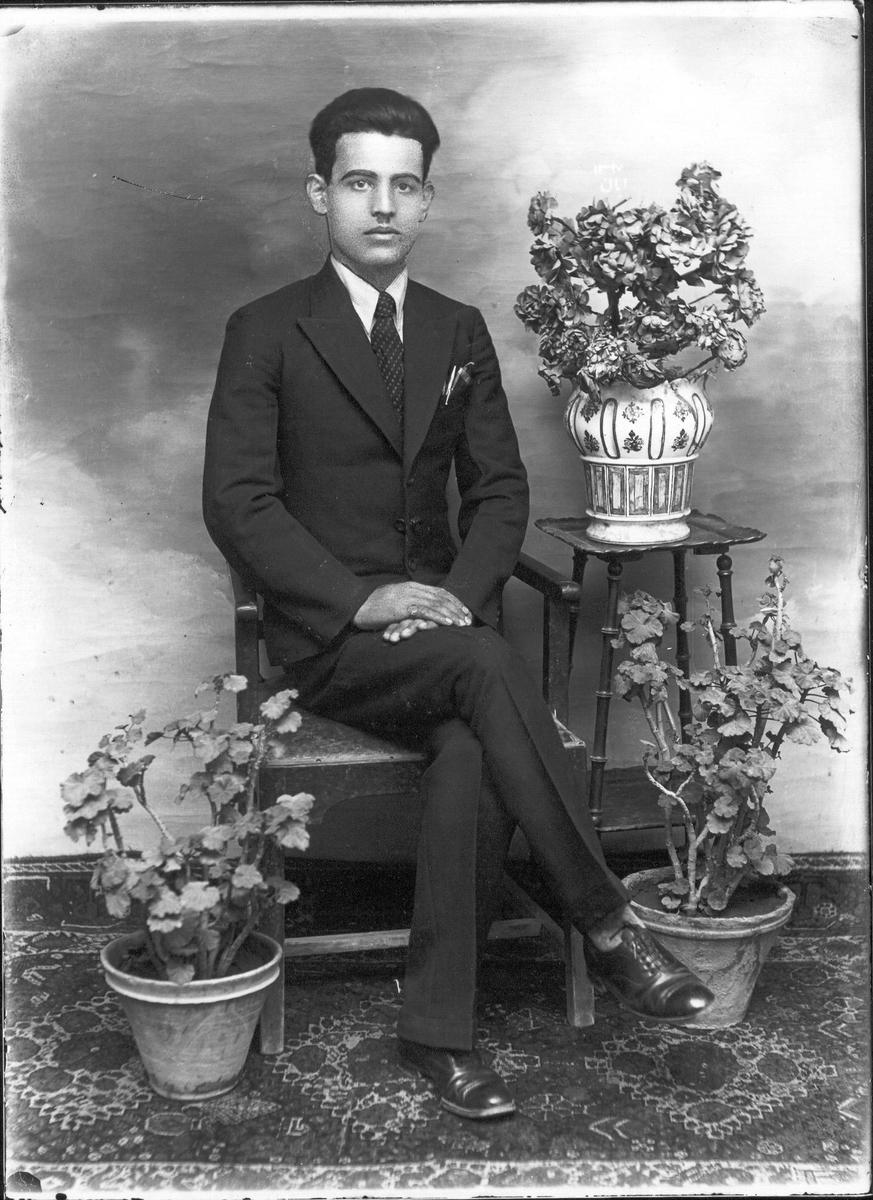

While Qajar court photography had its own trajectory, the story grew more interesting with the public’s first encounter with photography (it always does) — the birth of the earliest studios and later-ruler Reza Shah’s mandate that every last Iranian must have a photograph pasted onto their identity documents. Looking at photographs from that era, one can’t help but note the discomfort in peoples’ expressions, hands, and gestures. To take a photograph of someone was to wield power over them.

And what of the studio era of the latter half of the last century? Nobody seemed to care about these technicians-cum-artists who manned studios that dot Tehran’s urban sprawl. I made my way into the city’s working studios in relatively systematic fashion, placing particular emphasis on the half of the city south of Ferdowsi Square (a remnant of Tehran’s belle époque), engaging the old men at studios Hollywood, Sano, Metropole, and so on — all in various states of function and dysfunction (both the studios and the men). I nearly cried when I entered one particularly musty subterranean archive and found that most negatives had disintegrated under the weight of decades of accumulated moisture. I did my best to scrape off what seemed a persistent fungus. Six hours into scraping, I realized that it was a lost cause. There were at least 400 boxes surrounding me — portraits, weddings, family images — and I could hardly breathe.

Accessing archives was never easy. Many had either been burned or were hidden away soon after the Islamic Revolution. Suddenly, taking photographs of unveiled women in the studio was deemed illegal. The specter of ranting paramilitary basijis, who in the initial years after the revolution served as vigilante, self-styled censors, frightened many studio owners, leading to the destruction of countless archives. Images of glamorous sexpots in studio vitrines were replaced with babies, men, and mullahs.

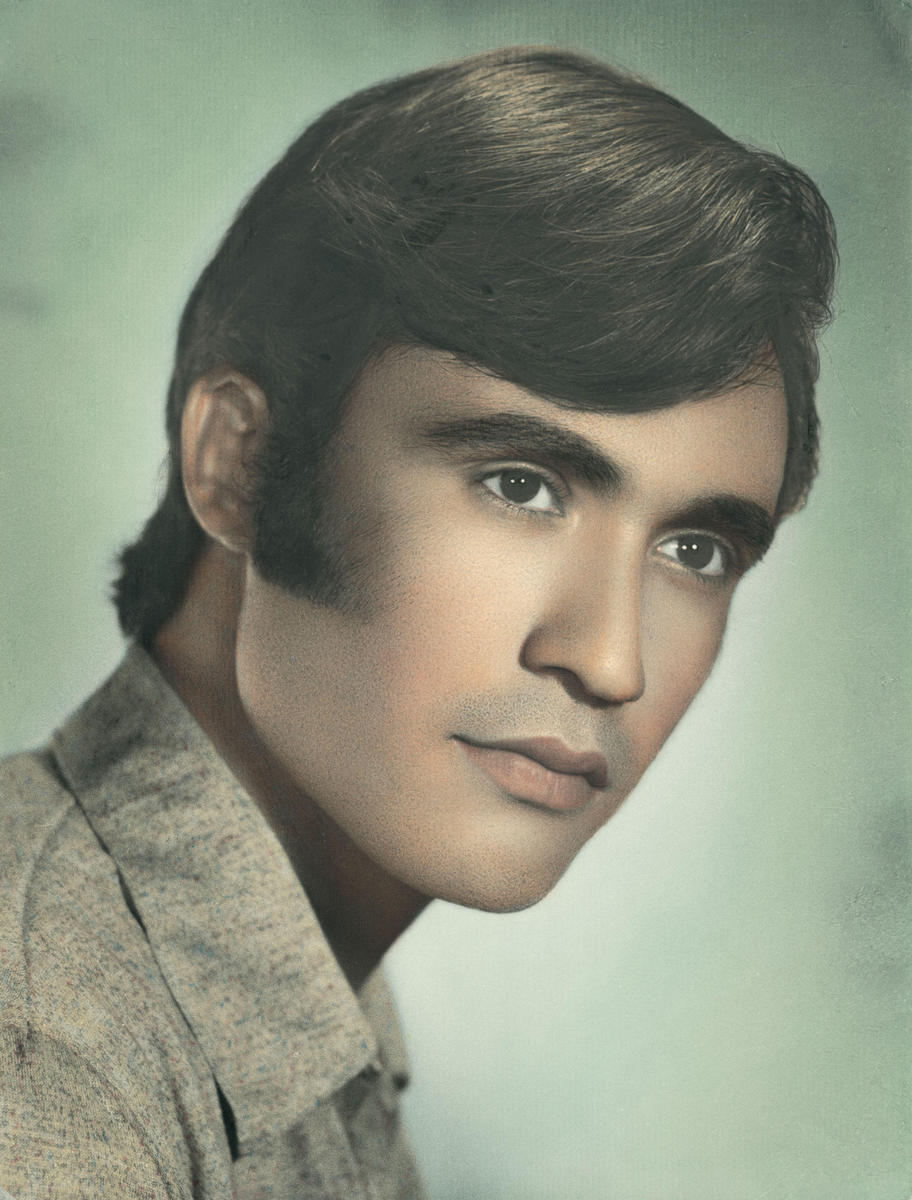

Photographic gems outside of the capital are in abundance, though. In one small studio in the southern desert city of Yazd, I stumbled upon a man who had not thrown his archives out during the revolution. Situated in the town’s central square was modest, cramped Studio Caron, its walls painted a sky-blue. I stopped in one day to take a seat among a row of old men, as the afternoon heat was leaving me dizzy. Minutes into our conversation, the proprietor, a sun-worn man in his ’70s who had trained and worked for years in Kuwait under a Lebanese photographer named George, pulled a box from under his front counter. Within this box were treasures — hand-tinted portraits from the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s. The saturated shades of magentas, blues, and reds were fantastic, reminding me of Studio Atro (run by Artin Sarafian) on Cairo’s Sherif Street. Some might call this sort of coloring kitsch. I call it a dying art.

In the meantime, back in Tehran, I continued my wanderings in the cemetery, exploring the ties between photography and national identity, history-making and politics at large in the Islamic Republic. The Iranian regime has an enormous command of visual imagery as a tool, whether in the form of commemoration of martyrs, design of postage stamps and political posters, or commissioning of street mural odes to the leaders of the revolution.

I left Iran after five months with one million ideas and a hope to return as soon as possible. The next stop is Kurdistan, on the Iraqi border, where I will pursue this story of the hand-colored images of martyrs that began for me that day in the cemetery.