In Dakar, the spirits ride at dusk. As twilight fades, the Senegalese capital turns eerily still, silent save for the crashing waves, the occasional yelp of a feral dog, and the hazy strains of music from unseen stereos. A clutch of young women take to the streets, possessed by the ghosts of their erstwhile lovers. Cheated of their wages by a greedy construction boss, the young men had set out for Europe and drowned under the night sky. Their avenging spirits compel the boss man to dig their graves as the girls stand by, their eyes like opals, dead and glistening. It is a kind of justice.

Director and writer Mati Diop describes Atlantics, which won the Grand Prix at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival, as a “ghost love story.” It is that, but the tale of star-crossed lovers belies a deeper meditation on power and precarity, told through the eyes of the left behind; in particular, Ada, our protagonist, who grudgingly agrees to marry a wealthy businessman who woos her with a gilded iPhone and a gaudy marriage bed, even as she mourns her lost lover Soleiman. As Ada deftly navigates a treacherous postcolonial landscape, the fault lines of global capital, class, religion, and patriarchy are cast in stark relief. Diop’s intention, she has said, was to capture Penelope’s journey, “not that of Odysseus.”

Atlantics is a sensualist’s delight, a painterly melange of onyx-black nights, blinking fluorescent lights, and textured interiors that channels the story’s otherworldly psychic states and, especially, its fascination with jinn, the spirits that animate Islamic and pre-Islamic mythology. Crucial to the film’s queer magic is its moody, unsettling score by Fatima Al Qadiri, whose music feels at once ancient and modern, enveloping listeners like a mist — or better, like the rippling sea, which serves as one of the motifs of this extraordinary film.

Diop is no stranger to the world of cinema. Claire Denis completists will know her from the film 35 Shots of Rum, a slow-burning family drama in which she plays Josephine, the brooding teenage daughter of a widowed train conductor. She’s also African film royalty, the niece of Djibril Diop Mambéty, the director of Touki Bouki, a startling film about young lovers on the run. (Touki Bouki won the International Critics Award at Cannes in 1973; Mati’s own 2013 film A Thousand Suns revolves around one of the nonprofessional actors in her uncle’s film.)

Atlantics itself was born of an experimental short that Diop made in 2009, also called Atlantiques, in which young men sit around a campfire, their faces lit like jack-o’-lanterns, as one relates his epic journey to Spain, from which he has just been repatriated. She is the author of six other shorts, including a breathtaking single shot of a young Michael Jackson impersonator (Liberian Boy [2015]) and a beguiling film-within-a-film about memory and belonging called Big in Vietnam (2012).

Diop’s collaboration with Al Qadiri is eerily apt for reasons that will become apparent in the conversation that follows. Al Qadiri makes music of rare and ecumenical taste. Her debut album Asiatisch (2014), is a musical meditation on the ways in which Asian themes have been appropriated by Western music; Brute (2016), was inspired by events in Ferguson and Baltimore and explores the sonics of global oppression and protest; Shaneera (2017), is built around an imagined pop star, a self-described “evil queen” of indeterminate gender who collages spoken word with Khaleeji grime and trap and chats drawn from Grindr.

Al Qadiri is also a member of GCC, the illustrious artist collective cum bureau of Gulf aesthetics. For Bidoun, she has penned classic pieces on Kuwaiti dating, being a kid during the first Gulf War, and her love for the band El Masryeen (“The Egyptians”), among other things. Atlantics is her first film score, for which she was nominated for a Cesar Award — France’s equivalent of an Oscar.

Bidoun invited Diop and Al Qadiri to talk about their remarkable collaboration, the burden and opportunity of representation, the appeal of zombies, and the lives of brown girls in a whitewashed world.

Negar Azimi: Fatima and Mati, I believe this is one of the most compelling collaborations between a filmmaker and a musician that I’ve ever laid eyes and ears on.

Fatima Al Qadiri: Aww.

NA: Fatima, the music you composed is unusually integral to the experience of Atlantics. In other words, it isn’t an afterthought. Nor is it a cosmetic “extra.” Its co-existent. You two really have pulled off some extraordinary magic.

Mati Diop: Thank you.

NA: At the same time, you’re both invested in overlapping intellectual themes: legacies of colonialism, histories of violence, the global movement of capital. All of it comes together in this gorgeous film. My first question is, because we have to do some scene-setting for our readers, How did you two find each other?

MD: I realized pretty early in the writing process that Fatima would be the ideal partner for this film. Even before I finished the first draft. Her music was in my mind the entire time. I’d discovered it back in 2011, when her name was still Ayshay. The discovery came as an aesthetic shock, arriving at a moment in my artistic life when I badly needed to be inspired and fed by a strong voice from outside the Western world. Fatima gave me strength, and with the distance I have now, I can say she’s probably opened doors for many women in music and the visual arts.

I’d wanted the Atlantics score to sound as if written by a jinn. And I wanted to choose a musician who had a personal understanding of the film’s geopolitical context. Given her own story, I felt Fatima could translate the various dimensions of the film: the spirit world, Islamic culture, the place of women. It felt important that the people I chose for the team reflect the spirit of the story. It was also extremely exciting to make my first feature with a musician of my generation who would be writing her first score. You know, Fatima, I recently found the letter I wrote you…

FAQ: You found it?!

MD: Yeah!

NA: You wrote her a love letter?

MD: Yeah, both to her mysterious website mailbox and on Facebook. I remember exactly where and when I wrote it. The moment felt so intense. I was writing to my hero, trying to convince her that we were meant to be!

FAQ: [Laughs]

MD: I knew that Fatima had been born in Senegal, so it gave the collaboration a karmic dimension. I liked the idea that the first sounds she had heard in life were in Dakar. That detail was crazy!

NA: Such a wild coincidence.

MD: Yeah.

FAQ: It really is.

Babak Radboy: Fatima, can you tell us why you, a Kuwaiti, were born in West Africa?

FAQ: My father was a diplomat working for the foreign ministry, first in Zaire, then in Dakar. They were there for maybe five years or so. Both my younger sister and I were born there, and then, in either ’83 or ’84, we moved back to Kuwait. I was two years old in ’83 and have no memories of it, just a ton of photos and home videos. I’d say my father was pretty bored when he was there. He was really just passing the time by going hunting with other diplomats. The diplomatic relationship with Senegal was cute, you know? There was nothing deep about it; it was of zero geopolitical importance. Because he had nothing to do, he made a lot of home movies.

NA: We should dig up those home movies. I’m curious about the role music has played in both of your lives. Fatima, what was your musical coming of age like? What did you grow up listening to?

FAQ: Like a lot of kids in Kuwait at the time, I wanted to find a way to express myself during the Iraqi occupation. We were living indoors 24-7, with minor outdoor excursions like crossing the street to the neighbor’s house, because it progressively became more dangerous with each passing week. But I wasn’t really good with words. I had trouble with both English and Arabic. Neither seemed to be my language. There was a keyboard in the house and one day, I started playing with it and memorizing patterns. I was like, Oh, I can do this. This is a melody; let me memorize it. And it mushroomed from there. We started buying bigger analog keyboards with our Eid money. Eventually, I got a tape recorder from my father and would record my compositions on cassette. I have no idea where those old tapes are, but I need to find them because they’re quite precious!

NA: Were you alone in your music-making?

FAQ: I’d compete with my sister, Monira. She was both my rival and my audience. I don’t know if I would’ve been the musician that I am today without her because she sharpened my skills. We were both very inspired by video-game music, its childlike melodic loops. Very early on, I knew that I wanted to be a composer, my dad constantly played the music of nineteenth-century Russian composers in the house. His favorite work was Scheherazade by Rimsky-Korsakov, which I would sit and listen to with him. He loved Eastern-sounding romantic orchestral works, whereas my mom would listen to ’70s Iranian pop divas like Googoosh and Hayedeh, equally romantic in sentiment but more accessible composition-wise. They both filled my head with melodies of Eastern romance. I don’t give them enough credit for influencing my taste in music. When I heard Scheherazade, I wanted to be able to articulate a melody like Rimsky-Korsakov. When I heard Googoosh, I longed to write music for a singer with her voice!

NA: Ooooo Googoosh. Fatima, she’s still alive and kicking in Tehrangeles. Tell me, were there other musical people in your family?

FAQ: You know, my paternal grandfather, Essa, was a singer on a boat, and his side of the family was extremely musical. All my uncles played instruments and sang, my grandmother as well. My mom told me that the first time she visited my father’s house they all sang and played music after lunch. She thought it was really weird. She’d never seen anything like it before.

NA: What kind of boat?

FAQ: A pearl-diving boat, a dhow.

NA: Oh wow.

FAQ: Yeah, yeah, yeah. They would sail from Kuwait all the way to India and back.

MD: Incredible. When you first told me that, I thought, This is intense!

FAQ: It was a very medieval occupation. You know what I mean? He would go away to sea for six months and then come back. He had a complicated relationship with his family. He divorced my grandmother a few years before he died and went off with some other lady. He was a gambler and a real seafaring macho man. He died before I was born, so I never met him, but there’s a lot of mythology and family lore about him.

NA: Mati, you grew up in Paris with a sort of Bidouni mish-mash background. What were you listening to at home?

MD: My father is a musician, you know, so the living room was basically my father’s studio. I have early memories of playing around, surrounded by guitars and amplifiers while he was working. Both my parents listened to a lot of music — mostly jazz, African music, and rock. And I would listen to opera with my French grandmother. She would tell me stories about her own mother, who sang at the opera on Sundays. Music was omnipresent in my family. As an only child, my imagination was pretty vivid. I was really into my own world, inventing games and so on, but mostly listening to a lot of different kinds of music. I loved making mixtapes.

BR: What was on them?

MD: My mix-tapes moved from black pop to French variety without missing a beat. Later, as a mixed-race teenager, music became more subject to my identity crises. I felt I had to choose between black and white. I went through a hip-hop phase, was obsessed with Aaliyah, and wanted to become an R&B singer. I spent an indecent amount of time singing in front of the mirror. Then I transitioned to a more grunge or gothic phase, which felt like a betrayal to my black side! It all got smoother when I discovered trip hop and acid jazz with Meshell Ndegeocello. I fell in love with her. I was very, very into her music. She showed me that I didn’t have to settle on a fixed identity anymore — everything could just converge. Soon after, I started playing bass.

NA: Meshell Ndegeocello was such an icon of the ’90s! You’re right that part of the magic was that she didn’t adhere to one style. Her music was an irreverent collision of funk and rock and reggae and other things. What was your father’s music like?

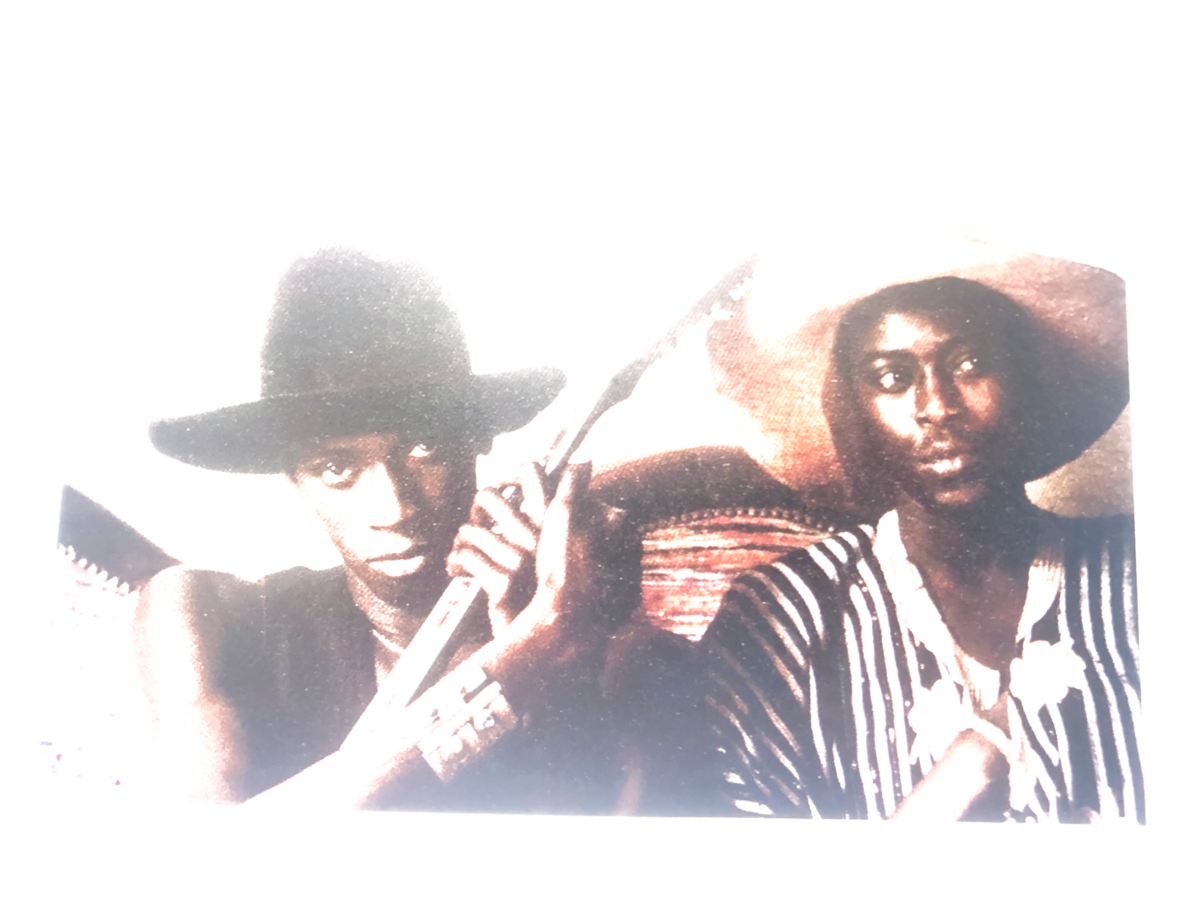

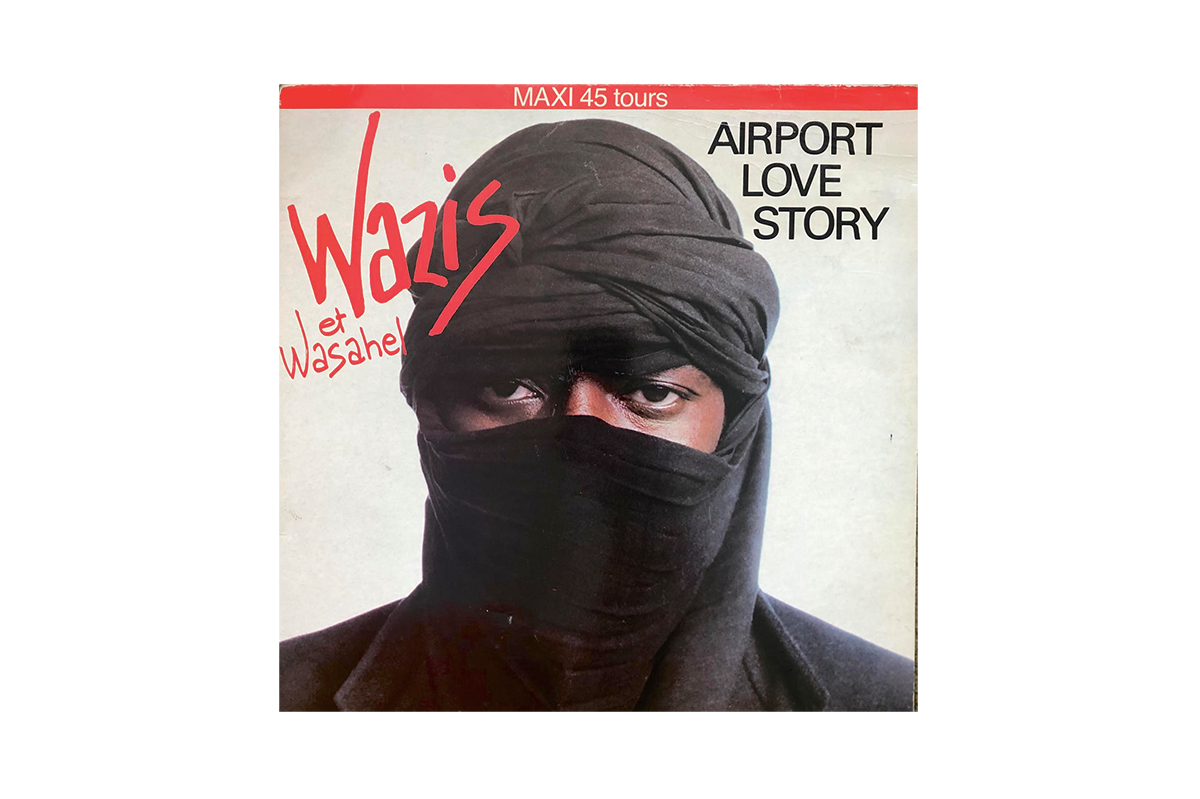

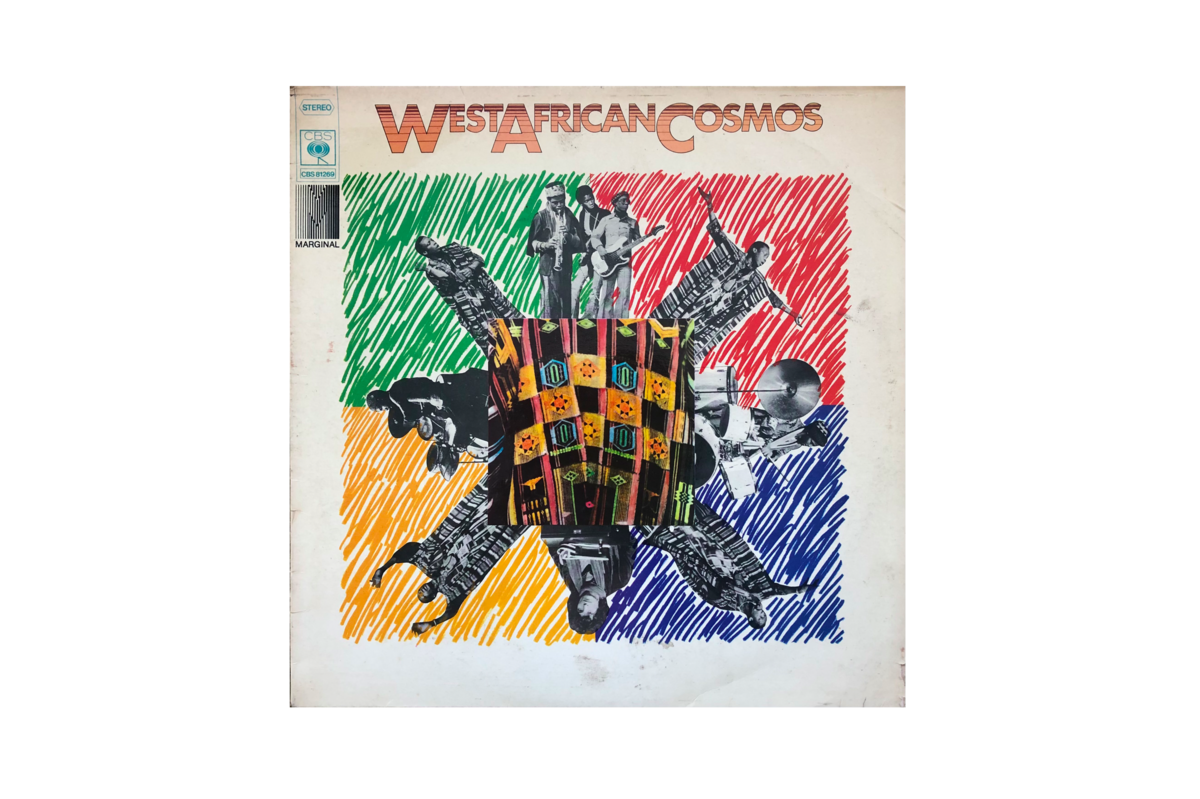

MD: It’s hard for me to describe. In the ’70s, he had a band called West African Cosmos, then he moved on to playing solo. I would call his music “Afropean folk?” He plays guitar, writes, and sings. His father was an imam and a very strict man. In Senegal, if you’re not part of a specific caste, you can’t sing, it’s forbidden, so my dad had to leave to become the musician he is today. The score he made for my uncle’s film Hyenas is one of the most powerful soundtracks I know. It really has marked me immensely.

NA: What’s so special about it?

MD: I’ve always wondered what was going on with him when he made that music. It sounds like he’s been possessed by his oldest Egyptian ancestors! It’s so deep and haunting. It feels very mystical to me. The score was omnipresent in my childhood, it shaped my image of Africa and was a strong antidote to exoticized representations of it. Oddly, my father is often considered one of the pioneers of what they call “world music.”

FA: Very cool.

MD: I don’t know… is it?

NA: Starbucks music…

FAQ: No, no, no. It’s so cool, girl.

NA: My friends who grew up in France who are of Arab and African heritage often say that they never saw themselves reflected in French cinema or music — only in hip-hop culture. It felt more consistent with their experience. Was there anything happening pop culturally in France that mirrored your interests or your mixed-up experience?

MD: I felt the same way, especially with cinema. That’s why Claire Denis’s films were so important to me. I could finally relate. In music, French rap was the only genre I could identify with because most of the rappers were culturally mixed like me. It was also an escape from a certain cultural heaviness that’s very present in France. Very elitist.

NA: Mati, how did film follow from music for you?

MD: Cinema was the meeting point for all the different arts I had been exploring up until then. I had spent some time making exploring sound and photography, but I found that cinema was the best way for me to build stories. Other people’s realities, but also my own. Music was my first love, but I was terrified by the abstract dimension of it. Like a drug that’s too good, that takes you too far. Music felt too vertiginous for me, like a void. Of course, it’s also very mathematically structured, but still, I thought, I’m going to lose my mind if I become a musician. In a way, cinema is my own way of making music. Cinema also struck me as the most political tool I could touch in terms of impacting people, creating alternative narratives on a bigger scale.

NA: What did the collaboration between the two of you look like?

MD: I flew to Berlin to meet Fatima. I think you had read the script by then, right? Or the outline?

FAQ: Yeah, yeah. I got the script I think a month before you came to visit me in Berlin. I remember reading it in the doctor’s waiting room. I was getting a blood test, and it was the longest wait, so I finished it in one go, but it was still difficult for me to read. The film is in Wolof, and the script was originally written in French, and I was reading an English translation. So reading it was a bit weird, like, This is not the language that it’s supposed to be written in. It was like a translation of a translation. You know?

MD: Yeah, reading scripts isn’t an exercise I enjoy, so I understand.

FAQ: But even while reading it, I was like, You know what? I’m sure there’s something interesting going on here. Then, the night before Mati came over, I got the most intense food poisoning. So when she came to my house for the very first time, my face was completely gray. I was so, so sick. For me, it was a disastrous meeting because I couldn’t even be myself. I was like half a human. No one had ever come to meet me from another country before, and there I was, just so dead. I felt bad for both of us.

MD: From my point of view, it wasn’t that bad. First meetings are always a bit awkward anyway. When you have a lot of admiration for another artist, and you really want to work with them, there are expectations, so I was also a little nervous. Now that I know you, I realize you’re very different… You were a little cold, right?

FAQ: I was definitely cold — I was the zombie version of myself!

MD: You were.

FAQ: Eventually, I came to Paris to see the first edit of the film. That’s when I really, really started to get excited about the project. I think the first edit I saw was two hours and 40 minutes or so, a very long cut. I remember when I saw the early scene of Soleiman on the truck looking out at the ocean, I was like, I don’t need to see any more of this film. I was convinced.

NA: The song you wrote for that scene is so beautiful. It’s ominous, too. Of course, only later do we realize why. As Soleiman is looking out at the sea, he’s thinking about leaving for Europe that night.

FAQ: It’s crazy because that’s the first song I wrote for Mati, in a hotel room in Tokyo — I was there for a gig. She had said something about my music tending to be dominant and overwhelming, and my needing to pull back a little bit, and she was absolutely right. The style of music I had been making was always very extra, very dominant… I’d never made space for actors and acting, you know?

MD: There was this very rare and singular instrument on the track, the Hohner Guitaret, which I loved, but we were missing a more vulnerable and melancholic dimension. I really wanted this moment to feel like a song for the end credits, like we’re saying goodbye to the boys, conjuring a tragedy. We know that they’re not going to come back from their voyage. Fatima, I felt like I was really pushing you to find more and more fragility. It was a beautiful process for me to take you there.

FAQ: Mati’s feedback was always right! [Laughs] Sometimes I got frustrated because I wanted her to love the first thing I had made, but the track that ended up in the film was always a zillion times better than my first attempt. She challenged me! I’d never worked with feedback before. [Laughs]

BR: I wanted to talk a little about the plot of the film, how it revolves in part around the spirits of a group of boys who return from the dead after they’ve lost their lives at sea, trying to get to Europe. They end up haunting the boss who hadn’t paid them for the work they’d done on his construction site. All of which is to say… I hoped to have a conversation about zombies. When I heard about your film, I was also making a film; part of the research was about zombies, and I became a little obsessed with these figures. It also involved a lot of readings in Afro-pessimism.

FAQ: Afro-pessimism?

BR: It’s real. [Laughs] But what interests me is how the figure of the zombie comes from slavery, specifically from West African folklore, and is a premonition of the idea of social death. The first zombie film was White Zombie, which was set in Haiti, about a white plantation owner who has zombies instead of slaves following the country’s revolution. In Night of the Living Dead, the first major zombie film, the savior-slash-sacrifice is a black man. In general, this confrontation with the zombie is a confrontation with the poor.

MD: What you say makes me think of a very formative experience I had when I was shooting Atlantiques, the short, in 2009. At the time, there was a massive wave of departures of young Senegalese for Europe. It was both confusing and terrifying to me, the fact that the coasts for which these young people were leaving were also the starting points for the slave trade their ancestors took part in hundreds of years before. How could history present such vicious cycles? What I was witnessing suddenly made that terrible past so palpable. The atmosphere of the city was very dark because all these boys were obsessed with leaving. When one of them told me, “When you leave, you’re already dead,” I started to envision Dakar as a ghost city, a city of the living dead. The idea for the feature really came from that experience — of grappling with a generation of youth being sacrificed.

But the film stands against a certain Western Afro-pessimist perspective and was also very much inspired by the riots of 2012, the “Dakar Spring,” when people took to the streets because the president had threatened to extend his term. The end of the film is very explicit about empowerment. A young black woman looks at herself in the mirror for the first time and considers her own future. I didn’t want to imprison my characters in a pessimistic perspective. You can’t reduce Senegalese youth to migration and loss because that would confirm, to a certain kind of viewer, that Africa is doomed, that it’s destined to perish.

NA: I’m curious about how you decided to represent the boys’ possession on film.

MD: At one point I envisioned the boys coming back from the ocean with white eyes, all wet, wandering around the neighborhood at night, sitting down in the girls’ beds, whispering in their ears about their shipwreck. Then I felt that it would be much stronger if they were invisible. The film is about how ghosts come from within the women who stayed behind. I also wanted to refer to the jinn, to the local Muslim culture. I loved the idea of the girls passing out during sunset and sweating from fever. Fatima, I remember you told me that the jinn in Kuwait come out at noon, which I found even more terrifying, but in Dakar they come out at dusk. It’s a moment called timis. In fact, I almost called the film Timis! But the feverish sweat wasn’t enough — I needed a clear physical sign to indicate that the girls were possessed. The white eyes came to me right away as almost a childish archetype of the living dead. I liked that it was so universal and direct, and I liked its erotic dimension, too. This archetype of the black figure with white eyes was very evocative to me. It drew on the image of the black Atlantic, the story of the Middle Passage, which to me mirrors contemporary migration. I wanted the spectator to be able to project different mythologies related to black history onto this figure: the zombies of Haiti, the ghosts of the transatlantic trade, and the spirits of the boys of today. Like one and the same story, one and the same myth.

NA: I’m interested in your decision to embrace the supernatural, which struck me as so seamless. It didn’t feel like a labored twist when it happened — the possession, I mean. It felt very natural. It made me think of that Godard quote from Notre musique (Our Music): “The Jews become the stuff of fiction, the Palestinians of documentary.” I don’t want to typecast this film as “African cinema,” much as I wouldn’t want to typecast your father’s music as “world music,” but we expect something of National Geographic and the documentary when it comes to Africa, and this supernatural turn, or whatever you want to call it, was really idiosyncratic. I wonder if that was important to you, especially when you think about the ways in which we tend to experience cinema set in African countries.

MD: I’ve always hated the fact that people call anything that isn’t Occidental “world music.” It implies a hierarchy, an “us” and a “them.” It also cancels the complexity and uniqueness of artists from very specific cultures under this one vague label. You know how an African film is expected to be, what a western audience is expecting to see. My cinematic language is a sort of resistance to these expectations. You could say there’s a reparative dynamic in my cinema, almost as if by creating a new landscape I’m healing myself from having been exposed to colonial stereotypes for too long. Each face, each image and frame is set against those stereotypes and offers up a new image of ourselves.

BR: Along the same lines of this not being an Afro-pessimist film, nor an American film, I hoped to talk about violence. The thing that I kept watching for and that stood out to me was how the zombies in the film, when they return, invade private property but avoid any violent retribution; instead, they reason with the boss. I feel like whether or not there’s violence in the return is a crucial question, right? Or, put differently: Why was there no violence in the end?

MD: That’s an interesting question. Initially, Fanta, the leader of the possessed girls, was supposed to have a more confrontational fight with the boss. In the script, she grabs his throat and pushes him down on his knees. But when we were about to shoot it, it didn’t feel organic, I just couldn’t figure out how to make it happen. It suddenly felt a bit fake…

BR: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Your next film is going to be much more violent!

MD: The violence in the movie is not American style, with guns and punches in the face. The film roots itself in the reality of social violence: how the boys have no choice but to take this boat because of the violence of capitalism, or how a girl like Ada’s only strategy for survival is marrying a rich man who made it to Europe. Ada embodies the steep price of becoming an independent woman in Dakar today. And so, the violence of the film is not specifically in the revenge-genre idiom, but more in its political background: the postcolonial, patriarchal and capitalist society. How this system pushed a whole generation to leave and die at sea; how it destroyed Ada and Soleiman’s love.

FAQ: For me, these themes played out through the tradition of jinn — I’ve never heard of any jinn story in which the spirits are violent, where the jinn physically attack someone. Their entire purpose is to instill a really deep fear in the subject they’re haunting. Some of them have goals, some of them don’t, but I think the lack of physical touch in an encounter with the possessed is very true to jinn mythology.

MD: Like you say, Fatima, I was conjuring an internal power, something hidden, playing out through the tension. I guess I have a very strong belief in cinema, in its capacity to create fear through invisible and subtle means.

NA: Mati, what about the decision to make this a love story? The not-so-crypto Romeo and Juliet aspect. How did you arrive at that?

MD: Well, like I said, my initial vision was to dedicate the film to young people who disappeared at sea in the 2000s. Then, when I decided to tell this story from the perspective of a single young woman, it felt obvious to hinge it on a relationship, and the loss of a boy. A love story. The character of Ada was inspired by the young woman you see in my short film, Atlantiques, which was shot in 2009.

NA: The short, in which a group of young Senegalese youth sit around a fire and talk about the passage to Europe, also has a supernatural aspect to it.

MD: She’s the only character who doesn’t speak in the short. I filmed her at her brother’s funeral. Eventually, she became Ada in the feature. When I decided to tell the story from the perspective of a woman, I immediately envisioned a black Romeo and Juliet, because I’ve long felt the absence of strong black love stories in cinema. With the exceptions of Touki Bouki and Black Orpheus, I hadn’t grown up with images of black love. There are African films, they exist, but it was always a battle to find them. They weren’t really accessible. The desire to tell a black love story is really based on the major absence of such a thing.

BR: It’s crazy. We face the same issue at Telfar, the fashion line I work as creative director for, in the production of images. I can really feel what you’re saying. You’re like, Have I ever seen a picture of a black person in the snow? Simple things.

NA: Skiing! Do you ever see a black person skiing?

BR: Yeah, it’s like, We can make the first image!

MD: It’s literally this. I asked myself, Have I ever seen a young African couple kiss with desire? Until I shot it myself, I had never seen it in a movie. It’s funny you mention a black man in the snow, because in my previous film, A Thousand Suns (2013), there’s a very long shot of an African film walking in the snow. So if you haven’t seen a black man walking in the snow, you can watch my movie and cry. [Laughs]

BR: [Laughs] I can’t wait.

MD: Are you guys familiar with the work of Kevin Jerome Everson? He’s a black American filmmaker and artist, who made an incredible film called Erie, about the lake.

FAQ: It’s pronounced “Eeeerie.”

MD: Yes, he mostly films the black working class. In one of Erie’s most memorable scenes, we see some black people visiting Niagara Falls. To add to what Babak said, the image was a big deal for me. I’d never seen black bodies traveling for pleasure in a film, traveling to just be…

NA: Tourists.

MD: Tourists. Being tourists, you know?

NA: I don’t think the Huxtables traveled.

BR: No, they didn’t have the budgets for that.

FAQ: Oh my God.

MD: And just to finish my point — this is one of the reasons, not the main one, but maybe the subconscious reason I was excited to encompass different genres. The absence of black characters was so pervasive in my youth that I felt the need to multiply the possibilities in the space of one film: a love story, a crime investigation, a coming-of-age story. There are so few situations in which these genres are embodied by black people, so my attitude was: Let’s touch as many genres as we can in a single film. Let’s wildly explore! It will be both a huge liberation and a fucking pleasure, you know?

NA: Totally. And somehow, the film doesn’t feel burdened by cycling through multiple genres. What about the wedding genre? I love the scene just before Ada’s wedding, the one introduced by Fatima’s track “Yelwa Procession.” There’s an incredible claustrophobia around this ostensibly happy moment as Ada is getting ready to be married to Omar, a rich douchebag who in a previous scene tells her, in all seriousness, that having an iPhone will change her life. Of course, as viewers, we know what Omar doesn’t know, that Ada is mourning the death of her love, Soleiman. Fatima, I’m sure the subject of the scene resonated with you as a Kuwaiti. Arranged marriages —

FAQ: Oh my God, absolutely. There are so many scenes and environments in the film that I relate to. Okay, the wedding, with the exception of the women coming out of the cars and clapping — because we don’t do that, we do that inside the space — the prospect of a young girl being forced to marry someone from a wealthier family is totally familiar… I related so deeply to the film, and to many of its subjects: jinn, social justice, migration, identity, love, obsession…

MD: When I listened to Fatima’s track “Yelwa” for the first time… It’s so strange. It sounded to me like a complex nightmare, you know? I looped it right away because I was obsessed by the intro. For me, it’s really one of the most orgasmic moments in the film. I was entranced by it in the editing room, the sound of the ocean and the very ancient chanting of women. Like a sound coming from afar. It’s very tricky to shoot a wedding scene in African or Middle Eastern or Indian cinema, as it’s become such a tired trope. You know how westerners have reduced it to folklorism, to a cliche. So for me, it was really a big challenge to repair this corrupted idea. If I’m going to shoot a wedding scene in Africa, it’s as if I need to kill the enemy inside me, you know what I mean? It’s like a revenge scene. As a director, it’s like an act of revenge against the colonial narrative.

NA: You reveal it then you set it on fire…

MD: I mean, I’m going to show it to you as it is, but you’re not going to get what you expect. I didn’t want to fall into that primal feminist perspective either, you know? I wanted to show that for Ada, the wedding is a nightmare because her love is out at sea, but it’s also her own strategy. She knows what she’s doing. It’s her own strategy of survival. And the music of the scene was the strongest force in turning it into something both very contemporary and very mythical.

FAQ: Yeah, and anti-folkloric.

MD: Exactly! But if you had told me at the age of seventeen that I was going to shoot an African wedding scene, I would have been like, “No way!” At the time, I was possessed by — the West, you know?

FAQ: Wait. I want to say something. Mati once mentioned these two words and I haven’t been able to get them out of my mind since. She said that she went through a “white period” in her youth.

NA: Oh, tell us about that, please.

FAQ: I went through the same thing. I feel like so many of us, either kids growing up in the West or coming to the West, have had this overwhelming need to fit in and to consume white culture. And then years pass, and eventually, the slow process of reconstruction begins. It takes years to break free of the white period, you know?

NA: What did your white period look like? Both of you? I, for one, wore a lot of Gap Kids when I moved to America, like it was a uniform.

FAQ: For me, my white period was about cultural consumption. It wasn’t only clothing; it was also the music that you listen to, the friends you befriend. You know, expanding your white circle. But also the movies that you watch. You’re desperately trying to fit in. When I came to America, I was seventeen, and I wanted to fit in so badly, you know?

MD: And you have no consciousness of it as it’s going on. It’s only years later that you realize what’s happened.

FAQ: Yeah. And it takes a long time to unlearn everything you’ve learned.

NA: You’ve been colonized by the thing…

FAQ: It gets normalized, you know? It’s not only actions; it’s words, attitudes, phrases.

MD: It’s a spell. It’s being under the white spell. It’s a Western jinn.

FAQ: Western jinn! [Laughs]

BR: What did your white period look like, Mati?

MD: It’s very cliché, but I think the most violent manifestation of it was what happened to my hair. I straightened it… [Laughs] Only somebody who has been under the heavy pressure of white culture can understand the violence of this basic gesture, to go against the natural state of your own hair.

NA: Yes.

MD: If I had a new date with a white guy — they were all white at the time; my environment was entirely white — I used to freak out about my hair. If I had to go to the beach on the weekend, or if there was a pool, oh my God, it was really a drama. Like, When is the guy going to discover that I don’t have straight hair?!

NA: You’ll be exposed as non-white.

MD: Exactly. But now I have a lot of humor and tenderness about myself when I remember that period and the alienation I went through.

FAQ: [Laughs]

MD: What about you, Fatima? Do you have an embarrassing example?

FAQ: I mean, I have so many. I’m trying to think of just one. But I feel like my white periods definitely started the moment my feet landed in America. You know? It didn’t exist before, because I was in Kuwait, and the interesting thing about Kuwait at the time, in the mid-‘90s, when I was in high school, was the omnipresence of black American culture. The biggest female act on the radio, playing 24-7, was Aaliyah. And the biggest male act was Keith Sweat. So we were very, very R&B, all the way.

NA: Once again, proof that Kuwait is the coolest Arab country.

FAQ: I rarely met anybody who liked rock music. People who liked rock in Kuwait were the tiniest, tiniest minority. You couldn’t find them, you know? But then I went to Penn State University, in a very rural town in the middle of nowhere next to a huge state penitentiary. The majority of people there were white.

NA: Okay.

FAQ: I definitely wanted to fit in, so I started to… I wanted to impress white people because white people were in power. You had to impress them if you wanted to rise as a musician, as an artist, you know what I mean? They were the heads of museums and the heads of record labels…

MD: You had to be validated by them.

FAQ: Of course. And it took me a really, really long time to realize that. I think the first time I realized the error of my ways was at a dinner in New York after the opening of a museum show for an artist. There were only white people and then me. I was just someone’s date, so I was a stranger at this table. Everyone knew each other. And I was like, Wow, to be at an artist’s after-show dinner and be the only non-white person and be completely estranged from these people — it just shocked me that this was happening in New York City, you know? I just felt like I was in like a bad episode of Friends or Seinfeld or something, where you only see white people on the screen. It felt very old-school and segregated. And from that moment my brain started to… the cogs started to turn, and I was like, I don’t want this. This is horrible.

MD: For me, my shifting moment is when I acted in the Claire Denis film.

BR: 35 Shots of Rum.

MD: I think I was a bit on the edge of my white period. I had an audition, and the following day, I found out that I was going to act in the movie. I was already a great fan of her cinema, so it was incredible. But I didn’t know where the project was going… Have you seen Trouble Every Day?

NA: Yes.

MD: So I was hoping that it was going to be a rock trash film like Trouble Every Day with Vincent Gallo, you know? Because Vincent Gallo was my ideal at the time, as an actor and as a man. I was very fascinated by white-trash America. I was very into Harmony Korine, etc. And so I was hoping Claire’s new film would be close to that vibe. When I found out that I was going to play the daughter of a black man working in the subway, I was so disappointed. [Laughs] The title of the film is 35 Shots of Rum, because rum is an alcohol that people from the Caribbean tend to drink. And so it was definitely going to be very black — not cool at all for me at the time. My fantasy of sharing a cover with my idol Vincent Gallo fell apart. It was going to be a “social black film.” Being revealed to the world as the daughter of a black man and being filmed with my natural hair was going to be a challenge. But in the end, it became like a ritual of dispossession that forced me to accept myself as I was. I had read Frantz Fanon, I was aware of my own alienation, but I was still under the pressure of it, you know? Acting as Josephine in that film was an enormous shift for me because I was obliged to come out.

NA: It was your coming out.

MD: Yes. I came out and started making films in Dakar, and I started to —

FAQ: Deconstruct.

MD: It was the year of deconstruction! A couple of months later I was in Dakar shooting my first film, Atlantiques, the short. And at the time, I can tell you that Africa was anything but fashionable, especially in comparison to now. In the art and cinema world, nobody gave a damn about Africa. I felt very isolated and marginal making films there. Whereas now, fashion is obsessed with black bodies to an extent I find disturbing. Anyway, I went to Dakar to make films to reconquer my Africanness. Atlantics is really my victory over the Western jinn.

FAQ: That’s so crazy, baby. Now I remember that after that dinner I mentioned, I was so upset that I made the album Ayshay. It was a big deal for me to sing in Arabic, to get away from all the Western music that I had been listening to… I wanted to make something completely, completely removed.

MD: I think you can all imagine what I felt when I discovered Ayshay the first time. I felt that we were speaking the same language. The first thing I said to Fatima in my letter was that when I discovered her music, I felt it was something I had been waiting for all of my life without knowing it. That the music of my time and my reality had finally appeared. You know?