One of the few mediums availed to dissident expression from the seventies that managed to survive the Turkish military coup of 1980 is the tradition of humor magazines. While the junta (1980–83) imposed occasional restrictions on their publication, today the pressure on such magazines comes from a neoliberal bent, as politicians attack them with accusations of defamation and beyond. Current Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan, for example, recently won a court case against a cartoon artist who portrayed him as a cat. The perplexing judicial decision against this relatively innocent caricature provoked the magazine Penguen to publish a cover depicting a zoo filled with various animals possessing the facial features of the prime minister.

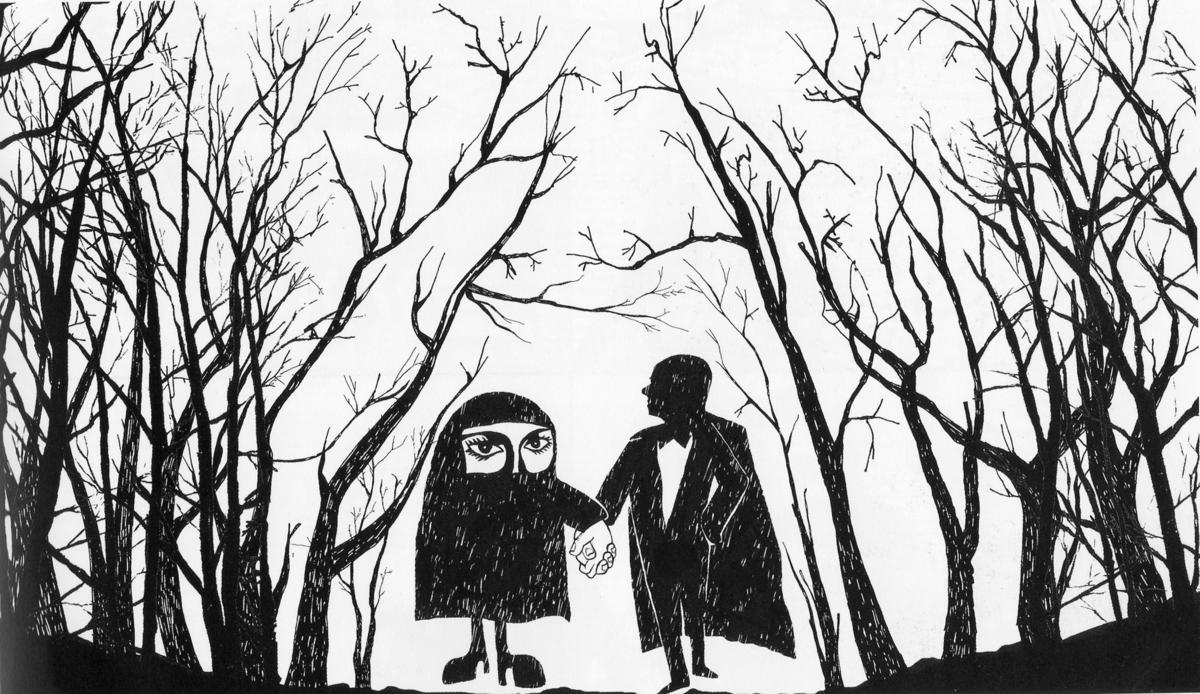

Memed Erdener (aka Extrastruggle) works in the contemporary art realm, but his formative years were marked by his contribution to a humor magazine called Deli, a short-lived publication that infused the humor tradition of Turkey with a taste of the grotesque. His works are assemblages of various pieces of Turkish visual culture taken from the nation’s history: maps and arrows about the myth of national exodus from Central Asia; anachronistic illustrations and expressions borrowed from the primary school books still devoted to the early years of the republic; the tension between the Arabic and Latin alphabets; iconographies of the Kemalist, Islamic and fascist ideologies; and everyday images (logos of public companies and political parties, warning signs). When brought together, these disparate and sometimes contradictory figures play against each other and produce a third, critical ground of irony that interrupts the integrity of various political orthodoxies. Some of Erdener’s recent compositions coupled the fictive persona of a devout female Muslim with the sacrosanct image of Atatürk — two figures that could be understood, in a simplistic manner, to represent two opposite ends of a pole in contemporary Turkey. With a bit of naughty and amusing transgression, these works somehow managed to provoke the “nationalist sensitivities” of a number of public figures. A Kemalist painter-cum-writer went so far as to compare the strategies of the artist to those of Adolph Hitler.

Newroz is the annual celebration of the coming of spring, a centuries-old Mesopotamian ritual. In the eastern part of Turkey the celebrations have long had a flavor of political resistance. During this year’s Newroz, two juvenile kids burned a Turkish flag in public, triggering national hysteria. Turkish public squares, stores, windows, balconies, newspaper covers and TV screens exploded quickly with red color and crescent-and-star in white. How dare these traitor scum to burn the holy Turkish flag on the Turkish soil emancipated with the blood of countless shehit (martyrs) ninety years ago?

The republican history of Turkey has been one of perpetual crisis. Despite several severe ruptures from the heritage of the Ottomans, the traumatic loss of the empire (most prominently the retreat from the Balkans, the geographic heart of the Ottoman modernism) has shaped the national psyche of the young republic. The fear of further partition has produced various enemies at home (ethnic and religious minorities, communists, fundamentalists, cosmopolitans) and abroad (old enemies, all neighboring countries, most of all the red Moscow). The paranoiac need to reinstate the shaky unity of the republic has led to the creation of strongly iconic references of national identity. The omnipresence of the image of Kemal Atatürk (a post-mortem phenomenon) in every public office and most private shops and public squares is perhaps the most visible reminder of the threat of being divided or brought back to the “Ottoman darkness.”

Nationalism has always been a trademark of the history of the Turkish left, which failed to distance itself from the state and, more interestingly, from the army apparatus (the historical agent of ultramodernism since the late Ottoman period). Only the suffering born of a series of coups d’état helped a strand within the Turkish left to articulate a fully autonomous ground for radical politics. The contemporary art scene in Turkey is strongly linked to this manifestly anti-nationalist leftist strand.

Some socialist painters attached to modernism were imprisoned after 1980. But the first real friction between state authorities and contemporary artists was occasioned by an installation by artist Hale Tenger titled I Know People Like These II. The piece, exhibited in the 3rd Istanbul Biennial in 1992, consisted of two models of touristic bric-a-brac. The first Tenger used was a figurine of the hear no evil, see no evil, speak no evil monkeys, the second an ancient Anatolian god figure with a small body and a giant phallus. Brought together, these two pieces operated as an allegory of the domination and regulation of the local population by those who wielded power in the eighties and nineties. Configured in the shape of a Turkish flag, the effect was jarring. On the last day of the exhibition, Tenger was sued for offending the national flag. It seems that the mother of a shehit had made the complaint, though she remained unidentified.

Six years later another artist, Halil Altındere, was similarly accused of offending the decency of an official document. Several MPs of the Refah Partisi (Welfare Party), a religiously-based faction, made a fuss about Altındere’s oversized, simulated identity cards; one had a picture of a naked female torso on it. Clever defense strategies on the part of the two artists prevented a potentially scandalous punishment.

The nationalist paranoia has experienced a marked upswing in recent months. The negotiation process for membership into the EU has created obstacles for the official discourse on a number of hot-button issues, such as the fate of Cyprus and the tragedy that befell the Ottoman Armenians in 1915. Attempts for revisionism in state politics are being loudly opposed by a “patriotic” coalition between fascist and so-called leftist versions of nationalism. A witch hunt of sorts is being launched against intellectuals, academics, artists and activists who dare contest the nationalist rhetoric. Novelist Orhan Pamuk, for example, became the fascists’ scapegoat after publicly commenting on the nation’s guilt in the Armenian tragedy in 1915 and national complicity in the death of civilians during the recent civil war against the Kurdish separatists. A provincial governor ordered his books to be burned soon thereafter. The primary cultural field targeted by state conservatives remains literature.

While the visual arts have created a space for political engagement through narration-based practices, the powers that be still do not consider contemporary art practice a serious threat; the field is often perceived as a construct of the upper middle class, and until recently these transgressive works have scarcely found institutional support or space to exhibit beyond Istanbul. Such isolation has paradoxically allowed younger artists to claim an autonomous and radical zone for expression. Nevertheless, a series of emerging institutions, namely art galleries sponsored by banks and museums initiated by bourgeois families, have created a new and growing demand for contemporary art. The current dilemma of political production is how one may fit into these institutions without being subsumed by their agendas. Any collaboration that is not critical will damage the credibility of the politics at stake — the message, as it were. On the other hand, such novel engagements, if carried out in a critical, aware manner, have the potential to bring about unprecedented confrontations with both state power and popular conservatism. I would opt for this strategy.