London

Ahlam Shibli: Trackers

Max Wigram Gallery

July 14–September 16, 2006

As Ahlam Shibli’s exhibition opened in London, Israel and Hizbullah were declaring open war on each other over the capture of two and the killing of eight Israeli soldiers, which made for ironically serendipitous timing for viewing the artist’s images of the Israeli soldiers’ colleagues embracing. Shibli’s particular twist is that the soldiers she depicts are Bedouin, employed by the Israel Defense Forces primarily as trackers.

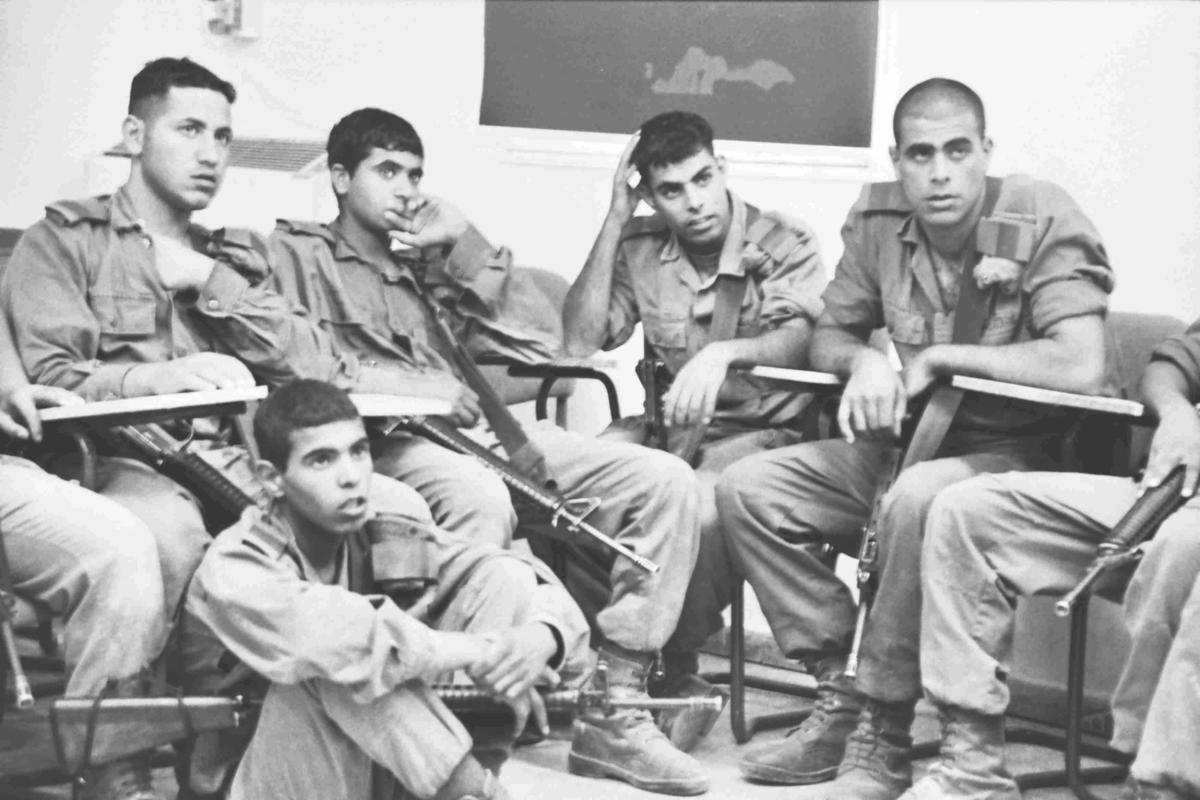

Her series of eighty-five black-and-white and color photographs depicts the soldiers — all volunteers; conscription is not enforced for the Bedouin within the Israeli state — as they start their training, go home on leave, and graduate. (It took Shibli seven months to obtain permission to shoot.) Looking at some of the photographs, it is impossible not to think of Rineke Dijkstra or Adi Nes for the fact that the boys pictured look so young, vulnerable, and sexy. Desire and war go hand in hand, as Jean Genet — among others — would attest to, and Shibli’s images fit neatly into the ongoing dramatic tension between the two.The Palestinian artist, born in Galilee and living in Haifa, captures face-on headshots of pouting boys smeared in camouflage grease,more laid-back portraits of the same boys in states of pure boredom or exhaustion, resting their heads against each other’s shoulders as they shelter from a simulated grenade attack, and others of them standing awkwardly, still in uniform, alongside their mothers at home. One soldier runs along a dirt road, his shoulders hunched, cupping a grenade in his hands as if trying to win an egg-and-spoon race — indeed in most of these photographs the boys look as though they could be taking part in some elaborate game or theatre.

Shibli’s shots of the boys together, loaded as their interactions are with gawky adolescent wariness and their desperate need to assert themselves, are particularly striking. In one photo- graph, two of the boys clasp hands and bring each other close; the looks on their faces display an unreadable combination of affection, attraction, domination, and contempt. Shibli has a Magnum photographer’s eye for a captivating photograph with just the right amount of punctum and studium, and many of the images in the series are bang on in their simultaneous fascination with the doubled Other side, and cool detachment from it.

In nos. 20 and 22 in the series a group of boys, home for the weekend, whirl through the desert on horseback and far into the distance, as if trying to escape their weekday lives, kicking up a trail of dust as they do. Number 23 shows a boy standing with his horse,his pose softened and relaxed. Shibli notes that ownership of these animals is the boys’ way back into their Bedouin identities, a means of reintegrating themselves into the desert lives that they betray by working for the occupiers. At the end of their three years’ service they’re given money for the downpayment on a house — these houses, some still being built, are photographed here amid the general dilapidation of the Negev, and with their high walls and air of isolation they sum up the perversity of the situation perfectly.

As well as showing the geography of the area, Shibli also takes still lifes of gravestones and the local graveyard with a few plastic chairs set up in it, of walls displaying photographs of soldiers inside the trackers’ houses, and the tents in the training camp — all of these displayed according to category. It is the photographs of the boys themselves, however, that remain the most desperately compelling. In her seminal book The Body in Pain (1985), Elaine Scarry charted how war is played out on the human body,and imagery plays an essential role in this process (for one textbook example, see the near-absence in the western media of images of dead or injured “Coalition” soldiers). These Bedouin trackers’ bodies, like those of every soldier, are so attractive because they are so easily blown up, torn apart, debilitated — or, as in the current context of Israel’s attacks on Lebanon and the Palestinian territories, captured, an act possibly more devastating to an iconography than mere violence. And this immanent fate is an essential part of their appeal.