We have no list — not in his letters, not in his voluminous diaries, nor in his various books of autofiction — of Hervé Guibert’s formative memories, those that might make up the carousel in a slideshow of his life. But from the texts and photographs, we can imagine:

• The tangle of his great aunt Louise’s hair, sprung out from her thick braids at the day’s end

• His father returning home at night from the slaughterhouse, his apron bloodied

• His mother’s carefully made up face

• His lover Thierry’s ass

• The white woolen garment he could never let go of as a child

• A menagerie of ceramic horses, marbles, marionettes, figurines

The French writer, artist, and polymath lived his thirty-six years with propulsive force. To this his work bears witness. He published seventeen novels in fourteen years; he was the long-standing photography critic for Le Monde; he penned trenchant correspondences and caustic love letters. He photographed friends and lovers, dioramas and details of paintings, himself in shadow, a delicate compendium of palm-size objects. He made a single video, La pudeur ou l’impudeur (Modesty, or Immodesty), in which he recorded his final year with the bravery of someone who understands time’s violence.

Guibert was born in Saint-Cloud in 1955, the child of an aspiring bourgeois family that would inspire his disdain throughout his life. He turned his back on his domineering father, a butcher; he recoiled at his mother’s primness. Contempt often serving as a guise for fascination, the three existed in a psychosexual vortex around which his adolescent life orbited. At seventeen, he moved to Paris, where his cool beauty and careful aesthetic eye quickly granted him access to the leading intellectuals of the time. He was Foucault’s favorite; Barthes pined for him.

Guibert wrote constantly: in his diaries (now collected as The Mausoleum of Lovers: Journals 1976–1991), for Le Monde and for the literature review Minuit, as well as stories and novels which flit between memoir and phantasmagoria, tracing impulse and desire with surgical precision. Ghost Image, his 1981 tract on photography, ranks alongside Susan Sontag’s On Photography and Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida.

His photographs? Hesitations, pulses, solitude, tenderness. He photographed to obscure the glint of death at the corner of his eye. The slim photo-roman Suzanne and Louise stages his beloved great-aunts in cadaver like poses, documents the arcane objects to which they devoted their lives; other collections take up the vibrancy of the body, to which he attended with a grace that recalls Simone Weil’s definition of prayer: “absolutely unmixed attention.”

He is often accused of having sold off his secrets, as if people haven’t met a writer before. His 1988 AIDS diagnosis only propelled him to work at greater speed. He gained national recognition and notoriety with the 1990 publication of À l’ami qui ne m’a pas sauvé la vie (To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life), a novel-cum-roman à clef that depicts with an unflinching eye the fear and mania of the AIDS crisis via a group of friends in France. The thinly veiled character Muzil, a famous author dying of HIV, was easily recognized as a stand-in for Michel Foucault, who had not disclosed his diagnosis prior to his death in 1984. The novel was read as treason, a ploy for stardom at the expense of friendship. But secrets do not necessarily violate the private life of the heart.

“I empty myself slowly,” wrote Guibert, early on in Mausoleum. “I exploit myself.” If this were his ethos, its ultimate permutation came with Modesty, or Immodesty, a video diary he recorded between June 1990 and March 1991. He vowed that “everything that could enter into the field of experience… could became a potential episode in the film.” “Everything” would come to encompass the banal and the sublime: medical appointments, a medley of drugs, conversations with Suzanne and Louise, sunlight in Elba, a staged suicide attempt, the persistence of life in death.

He died in 1991 of complications from an unsuccessful suicide attempt. A week later, the video aired on French television.

A possible epitaph? Better to remain hungry than to renounce appetite.

On the occasion of the republication of the English translation of To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life, the editors of Bidoun and Semiotext(e) invited six artists and writers — Moyra Davey, Lia Gangitano, Bruce Hainley, Hedi El Khoti, Wayne Koestenbaum, and Christine Pichini — to reflect on Guibert’s life, work, and ongoing resonance through his photographs.

–Janique Vigier

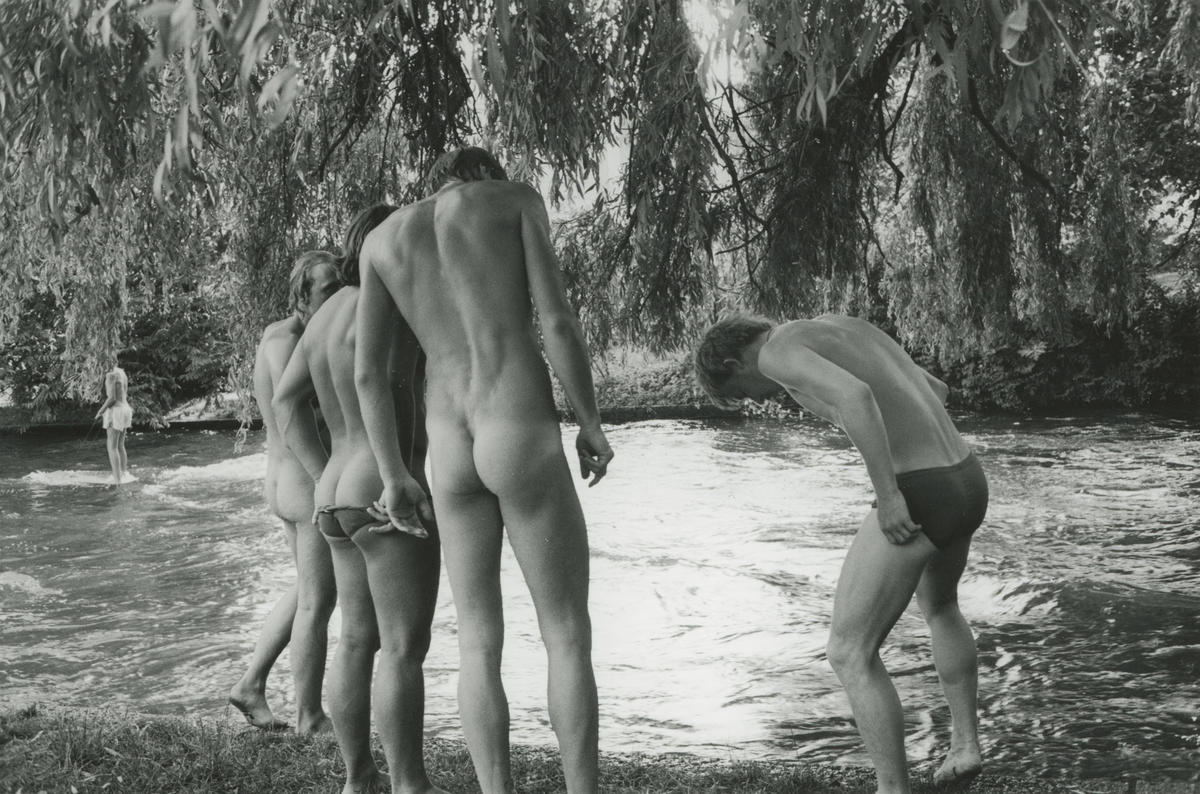

The Tingling Interregnum

Facedown on the bed the naked lover lies. The ass itself is not in question. At stake here is the lover’s effacement, the drapes, the dim light, the soles of his feet, the dreary tiled floor, the convent mood, and the black and white film’s wish to evade contrast and, instead, muffle its aggressions in a swaddling envelope of grey. The man lying down is Hans Georg Berger, a fellow photographer, a close collaborator. The reason that Hervé Guibert bothered to become an artist and a writer was to find a formula for intimacies, to turn photographed or described intimacy into a nearly psychedelic tincture dropped in the water glass of the daily. To avoid recording intimacies — however rude and potentially obscene these closeups, however in danger of being stigmatized as narcissistic or masturbatory are these exercises in mortifying the body parts of every beloved — would have been a recipe for paralysis. If Guibert had decided not to make a life’s work of photographing his intimate acts and his own body and the bodies of his aunts and lovers, if Guibert had decided to stop photographing cocks and asses because that subject matter is tacky, it is a crutch, it has no philosophy behind it, it is irresponsible, it is as time-wasting as philately or numismatics — if he had ignored Berger’s bucolic ass and photographed a riot or a ruin, then Guibert would have stunk, in that moment when he faced, posthumously, his Maker; Guibert would have smelled foul to his Maker, who would have rebuked Guibert for ignoring his calling and responding instead to faux-moral strictures that call ass photography a putrid performance, as false and glossy as a ceramic crabapple. I’ll revoke your death sentence, Hervé, his Maker might have said; I’ll send you back to Earth if you promise to photograph every erotic and abject moment of your life and death, every pincushion, every pustule, every taint, every crack, every horizontality that includes a lover’s body waiting for your embrace. Hervé was reluctant to return to Earth, but he didn’t want to displease his Maker, who was kind enough to understand the importance of pursuing the ass and pursuing the ineffable thisness of what actually happens to you and what actually turns you on — even if what turns you on also bores you, even if you would now rather kibbitz about tonight’s rainfall than go to La Coupole to find the accidental trick who will read you Balzac and remind you that you have betrayed your parents. Parentage, lineage, pedigree, entitlement, legacy — now that you are back on Earth for a second visit to the bedroom where Hans Georg Berger once lay facedown on the bed to give his ass to your camera, none of the signposts of having a name — of bearing an identity — matter. Is it ill-mannered of me to remind you that Guibert never got a chance to return to Earth? His Maker was not hearing appeals the day that Hervé knocked. Be grateful that Hervé photographed the ass, even if the ass doesn’t come equipped with language to defend its right to uphold its own puny law, the law of simply being there, being available, being a token of receptivity, vulnerability, steadfastness, and a state of equipoise between hardness and softness that makes the logician in me start fidgeting because I’d promised to clamp down on vagueness and bring you goods that are measurable and everlasting. We are at our least communicative and our most universal when we allow our ass to face the camera, even if the commentary we supply later, postmortem, seems to cancel the bounty that our silence, lightly dusted with hair (itself a synonym for the ineluctable), had promised. I told you that the ass was not in question. Maybe I was wrong. The ass is “in question,” which is another way of saying that the ass is dwelling in a tingling interregnum; the ass is waiting to be proved worthy. You verify its worth by circling it with as much fuss and intricacy as possible. Make a big deal out of me, suggests the ass. Overload me with ore. This photograph and this paragraph are sites of overloading, places where portents cluster as if on piers or in parks. The ass is a thesaurus where rough equivalences gather to commiserate, where a noun rubs against a near noun. A word (ass is a word) makes sense only when a contiguous word demonstrates that similar objects (my ass, your ass) are not the same. Not being the same, but almost being the same, is what the Maker calls succulence. That’s why I can’t stop being shattered by nude images, their staggering obstreperousness, their insistence on being superior to the occasioning flesh. A pair of buttocks caused the photograph. Causal buttocks, preliminary and disposable. What remains is this cleft document.

–Wayne Koestenbaum

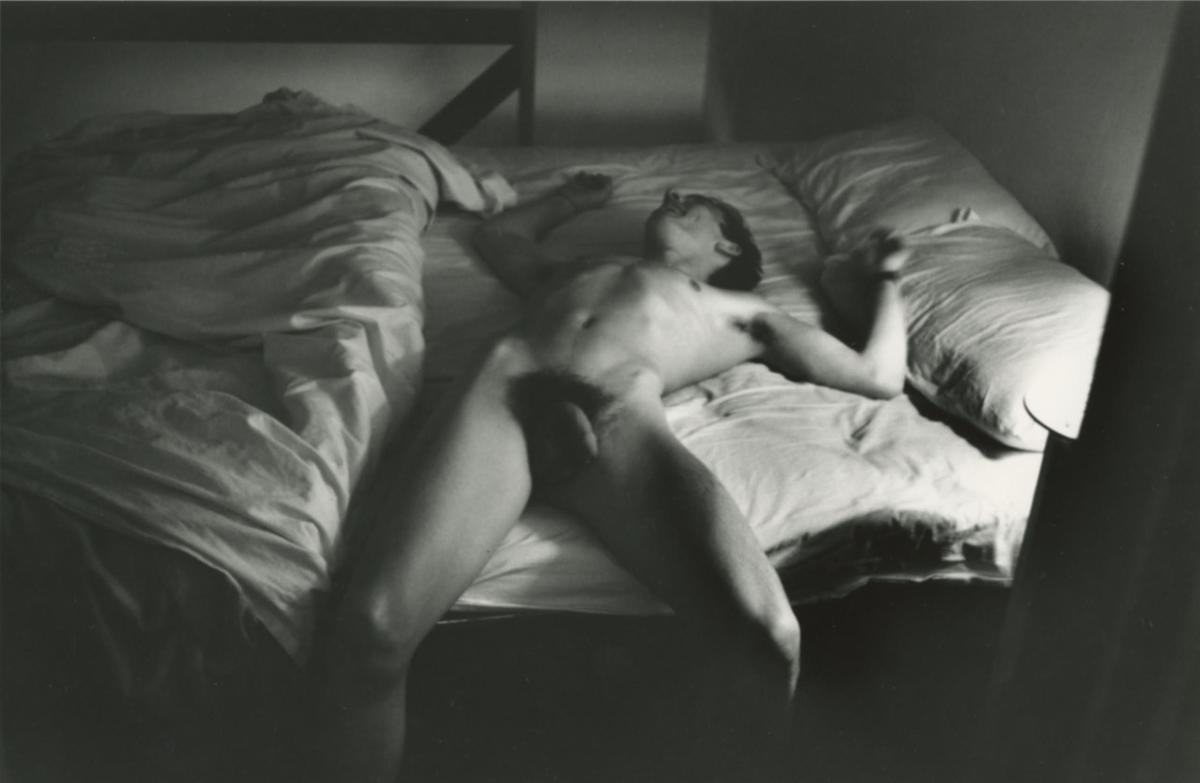

It’s tempting to quote him (HG), deadheading descriptive obbligato, “commentary,” my own voice (even more exhausting than the idea of commentary), to cherry-pick a few choice accounts from the journal about Vincent, whom Thierry, HG’s lover and the father of his wife’s children, called “a maggot and a shit” as well as a “glabrous gnome.”

I put both Le mausolée des amants and the translation of the journal by Nathanaël, The Mausoleum of Lovers, on my desk, but, even with my rusty French, I’m distracted by the word mausolée, with its terminal unaccented e making it look like it should be a feminine noun, though, preceded as it is by le, clearly isn’t. If I were Francis Ponge, I’d have a dog-eared Littré at hand to stroll along the etymological stream of the word to the source of why it came to be spelled the way it is; I’d find a malformed way to pun on the mausoleum’s mal soleil.

An online version of the Littré confirms the noun’s gender, derived from the Persian ruler Mausole, husband of Artemise, his sister, who had a magnifique tombeau raised in his honor. One of the seven wonders of the ancient world, revered not for its size but, until Christians demolished it, for its beauty, Mausole’s tomb soon lent, lends still, the interred satrap’s name, par extension, to every magnificent tomb, or “mausoleum” — which, whether or not wet with tears as in La Fontaine, the electronic Littré cautions shouldn’t be confused with “catafalque.”

Vincent Marmousez’s glans, his shaft, hopeful in the black plush of his thick bush, might strike some as this photograph’s raison d’être, but really, it’s his laughter. Teeth softly gleaming in his smiling open mouth prove his easy joy, ridiculousness a part of the entire erotic scenario. “Another picture? Of me?” I imagine him blurting out, before falling back onto the bed, laughing. Click.

HG loved this one, who called him darling — Last night, Vincent broke a glass against his forehead, insulted the servers of La Coupole, called me my darling, then in tears kneeled before me to kiss my glans — enough to kill him several times in various books, right at the start. Vincent came over to HG’s apartment to get stoned and fuck around — sometimes directly from his girlfriend’s, ready to party, pussy-fingered — or, since Vincent was often already stoned, to get stoned again and fuck some more. The last time he kills him in the journal, HG daydreams they’re in Martinique, wondering if it’s the start of another récit: Vincent éventré, l’abruti, sur la barrière de corail au large des Salines, je me retrouvai seul au bout de monde… (Vincent gutted, the bozo, on the coral reef off the Salines, I found myself alone at the end of the world…) A bad son under a bad sun. In Le paradis, HG’s last novel and my favorite, instead of calling Vincent a bozo, he has become Jayne (éventré shifted to éventrée) and is dubbed l’andouille, “the meathead.”

Why this picture now?

No death. Life in the midst of living. Someone being loved incandescently, knowing it, returning the love, not belittling it, with laughter, fleeting guarantor of truth. Before antiretrovirals became readily available. Long before deep-fried memes came to life.

Call it Once Is Not Enough — or, better, L’odeur des garçons, a title HG toyed with but never got around to using.

–Bruce Hainley

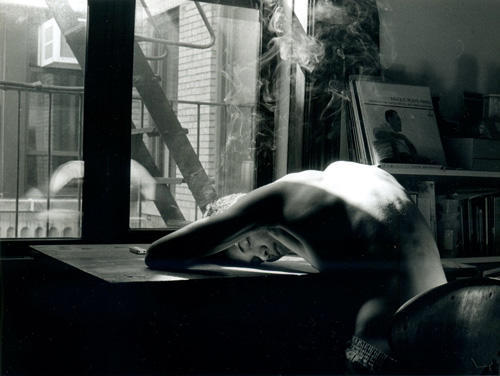

I came to Hervé Guibert by way of friendship. First, it was the artist Heinz Peter Knes who introduced me to Guibert’s photographs, and soon after, another artist, Pradeep Dalal, loaned me Ghost Image, Guibert’s essays on photography, which I quickly read and felt compelled to write about.

I had been telling Heinz about Francesca Woodman and showing him her books, which he had never seen, and he said: I want to introduce you to someone whose images have something in common with Woodman’s, and whose work occupies a similarly high place in my personal pantheon of artists. He pulled up Guibert on a search engine, and I could immediately make out the affinity.

Straightaway recognizable: Parisian apartments with their high windows and paneled walls and doors with dangling keys, and the particularity of the light that characterizes these spaces. Compositionally, they’re more classical and controlled than Woodman’s experiments with performance, disintegration, and the blurring of motion. But both artists have much in common: an old-world sensibility, a focus on bodies and interior space, along with expertise and control of black and white registers. Both spent considerable time living and working in Italy, where each staged photographs in rooms of similar genteel decrepitude bathed in southern light.

Not all of Guibert’s work is polite. There are many full-blown erections occupying center stage. If one looks beyond the essays in Ghost Image, to the fiction and autofiction and the collected diaries titled The Mausoleum of Lovers, there is fucking and shitting and some of the most forthright and courageous writing on the themes of illness and dying I’ve ever come across.

It’s hard for me to choose a single favorite photograph or text by Guibert. In my conception of him, pictures and texts inform each other and are part of a whole with many different valences: classical, scatological, erotic, angry, hateful, narcissistic…

A certain image has been made singular, though, by my son, who decided to restage Sienne, 1979, some years ago for a school assignment, using his good friend, Eric, as a model. Sienne is marked by light streaming through a high window and catching in its beams heavy curls of smoke hovering just above a man’s prostrate torso. I helped my son determine when the light would be optimum for his reenactment, and then I left him and his friend alone. The resulting photograph is a notable tribute to Sienne. Unlike the mythic Italianness of the original, my son’s photo is decidedly new-world, with a New York fire escape clearly visible just beyond the window in the courtyard. And yet the men’s shoulder blades are similarly highlighted and sculpted by solar rays, as is the white, swirling smoke. There is a suggestion of melancholia in Guibert’s Sienne, whereas I perceive in the image of Eric an homage to intoxication and friendship.

–Moyra Davey

First effects of Hervé Guibert’s Autoportrait, 1981: fascination, longing. An ache in the heart that travels along the crescent shadow parting his lips and aligns itself with the tilt of his jaw, a flutter of thrill at the glimpse of his face in the mirror. Guibert’s autoportrait flirts with his autofiction, that combustible genre which suspends real and unreal in search of a slippery “true.” I want to fathom his features, trace his curls. I want to look him right in the eyes, but our sight lines are ever so slightly askew.

Barthes writes that Avedon’s portraits of subjects who look us right in the eyes produce an “effect of truth,” that the gaze “acts as the very organ of truth.” But Autoportrait does something else. Shot in a (bathroom?) mirror, its trajectory of seeing toward being-seen and back again zigzags from Guibert’s eyes to the mirror to the camera’s lens. He shoots his reflection on a bias, a slant selfie from an invisible camera he holds in a hand just beyond the frame. If the studium is HG’s empirical beauty, the punctum is that kinked, ricocheting gaze. We hear the shot whizzing by, are wounded by its shards. And yet somehow it feels like a direct hit.

Seeking connection, I try to true the gaze, to place myself squarely in HG’s sights by drawing the photograph freehand. As if translating the image into a drawing could somehow consummate the act of seeing. Drawing as correspondence: a sort of séance or mystical conduit, the key to settling into the gaze’s groove. But every attempt to draw the photograph fails; the inky black eyebrows turn monolithic and severe, wrecking HG’s sublime face. I take a different tack — tracing — what I wanted to do in the first place; I trace his features with my fingertips, the photograph on a light box with small dashes, stitching together his face with pencil marks. I think about making a stop-motion-animation film out of these drawings, or maybe a shadow-puppet play starring Hervé and Isabelle Adjani, something about television appearances and AIDS rumors and betrayal, but while writing the dialogue, I draw a blank after “You’re breathtaking. / I know. / May I photograph you?”

–Christine Pichini

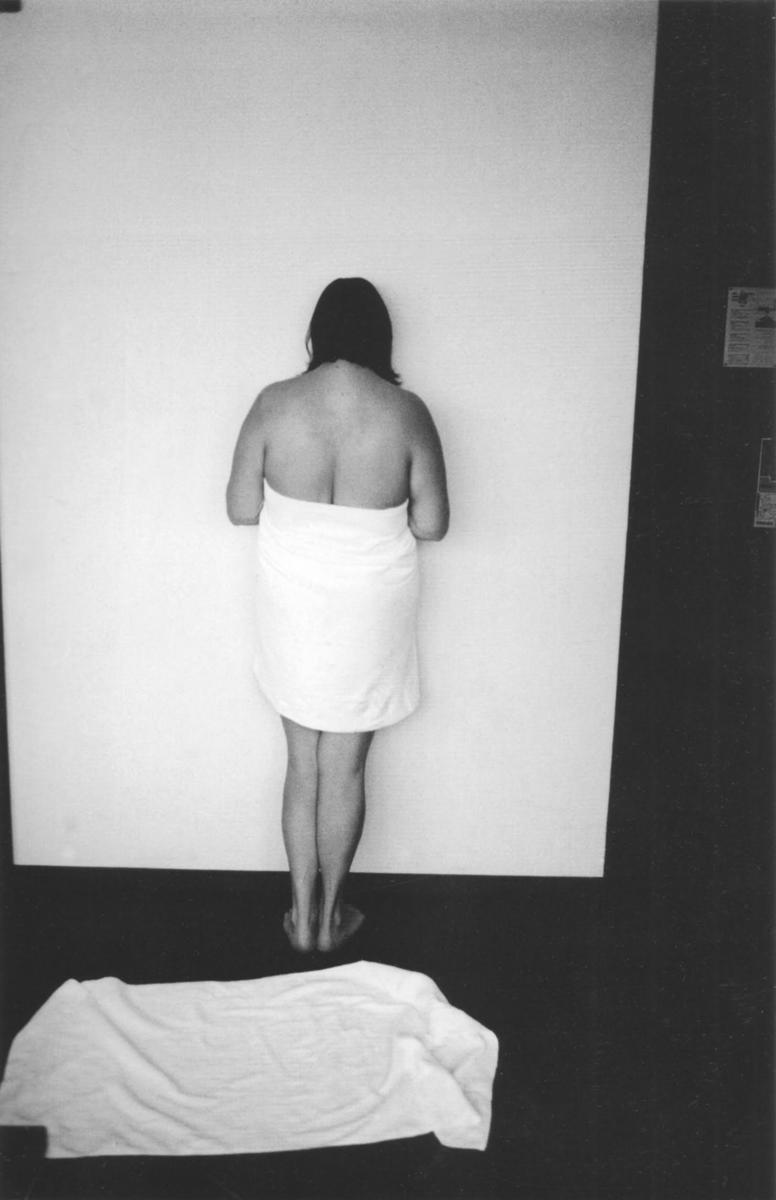

She Spent So Many Hours Under the Sun Lamps

There is something unsettling in Hervé Guibert’s austere 1978 portrait of French actress, singer, and model Zouzou. Standing in front of a white backdrop and seen from behind, she’s wrapped in a large white bath towel with her head slightly bowed. Another white towel, wrinkled and laid out horizontally on the floor, sets up a contrast between the towels and the surrounding blackness. The photograph, beguiling as it is, is an ambiguous invitation to imagine what we can’t see.

In Dusty Pink (1972), Jean-Jacques Schuhl’s elegiac novel composed of the smoldering embers of the 1960s, Zouzou appears as an emblematic protagonist of that period. Schuhl selects four moments — or movements, as if his book were a musical score — to create Zouzou’s portrait. The first collages newspaper captions to stirring effect: “Zouzou (the thin, pale, distant, smirking dancer [‘she’s the one over there with a British flag miniskirt, the most mini one in all Paris, when she goes to London she stays with George Harrison,’ declared Pariscope] syncopating her words, zazou zoulou — sophisticated savage.”

Pre-’68, she is Zouzou la Twisteuse, the famous nightclubber and fashion model, Brian Jones’s girlfriend and, briefly, Yves Saint-Laurent’s favorite model. “She had an androgynous style, which, compounded with her taste for revolt, made her a very modern character. She corresponded to what I wanted to express with my first collection. Sadly, we had to stop our collaboration after a few attempts; the discipline needed by haute couture, the rigorous fittings, the respect for schedule, didn’t suit her rebellious disposition,” the designer was quoted as saying in Zouzou’s autobiography, Until Dawn. Zouzou’s distinctive style had been perfected with the help of the artist and illustrator Jean-Paul Goude, her art-school boyfriend. She once recalled, “He cuts my hair really short… proposes that I wear very pale pantyhose, close to my complexion… forbids me to suntan… he loves my androgynous side, and pushes me to wear men’s garments… even paints color stripes directly on a beige sweater.”

In the second movement, Schuhl writes a three-line poem distilling the essence of Zouzou’s face, the face Guibert hides: “‘her lower eyelashes (and rings beneath) as if sewn on,’ ‘her nose as if broken,’ ‘her mouth as if painted.’”

The third movement alludes to Zouzou’s second movie with Philippe Garrel, La Concentration, a claustrophobic allegory of the filmmaker’s psychic crisis around May ’68. Here is Schuhl: “Strings and clips connected to electrodes are attached to her wrists and ankles for ninety minutes (fragile and synthetic).” Elsewhere, Garrel describes the largely improvised film, shot over 72 hours without interruption, as an indictment of spectacle: “We see two actors — Jean Pierre Léaud and Zouzou — rigged out with microphones, and confined in an apartment split in two zones, a cold room and a hot room, which are both torture chambers. A bed is set between the two spaces, encircled by camera rails.”

Neither Guibert’s diary, The Mausoleum of Lovers, nor Zouzou’s autobiography mentions the session which produced the photograph, nor do they disclose any memories of their encounter. Yet Zouzou describes posing for Richard Avedon and Helmut Newton in great detail: “Avedon is calm, levelheaded, discreet,” she recalls. “He takes very few photos. At the end of the session, he tells me, ‘You’re like Ava Gardner, in the way in which you can turn in two seconds from monstrous to sublime. It’s rare and that’s what I love most about women’s physique.’ Newton loves screaming. He needs a victim, the assistant or the magazine editor. With me, he plays the seducer. He portrays me as a tough bitch, forbids me to smile, and erases any trace of romanticism.”

At age twenty-three, Hervé Guibert is hired as a cultural critic for Le Monde, where he writes mostly about photography. Despite his youth, the breadth of his knowledge of the history of the medium is impressive, as are the seriousness and acuity of his criticism, emphasizing aesthetic criteria that could well apply to his own artistic project. In his 1978 review of a Lee Friedlander exhibition, Guibert writes, “Nothing happens in most of the photos. Absence of action, absence of sensuality, and even absence of meaning, since Friedlander shoots faces and traffic signs from the back. ‘A young girl, who knows nothing about photography,’ said while looking at Friedlander photographs: ‘There’s nothing wrong. But they give me a feeling of death.’ Nothing wrong, indeed, under the appearance of banality. As much as the preceding generation of American photographers (Weston, Caponigro, Adams, Cunningham) glorified matter, Friedlander cools it down.”

The same year, reviewing a retrospective by André Kertész, Guibert describes the Hungarian-born photographer’s work as “a pivotal oeuvre in the history of photography, which turns its back on the pictorial and portraiture while paying attention to all the small gestures that patiently weave life. Kertész’s photographs aren’t weighted down by an aesthetic discourse. They aren’t cold — not even the ones that seem to prioritize style. These photos could have been taken by anyone: they are the photos of an ‘amateur’… Kertész has said: ‘I see what exists.’ This isn’t naivety. It takes imagination to see reality.”

What does Guibert hope to convey of his 1978 encounter with Zouzou? The towel and the pose bring to mind the climactic scene in Eric Rohmer’s 1972 Love in the Afternoon, Zouzou’s best-known film. As Chloe, the bohemian object of a married man’s desire, she is down on her luck and trying to rebuild her life. Stepping out of the shower one day, she invites her admirer to dry her off with a generic white towel, much like the one in Guibert’s photograph. From there, the film moves toward its unexpected end, with Chloe alone and the man reunited with his wife. The character of Chloe was based on conversations Rohmer had with the actress around an unrealized TV series, The Adventures of Zouzou. At Love in the Afternoon’s New York Film Festival premiere, Zouzou made a triumphal entrance accompanied by Robbie Robertson and Jack Nicholson. At the after-party at the Factory, Andy Warhol, who loved the film, asked if he could take her Polaroid. At the Carlyle Hotel, she was accosted by dozens of fans. Obsessed with the Zouzou of the film, the critic Vincent Canby allegedly counted the beauty marks on her back.

Maybe Guibert sensed Zouzou’s need to retreat, to turn her back on her own image, to hide her remarkable face from the spotlight. He grants her that wish — a moment of respite. In 1978, the year the photo was taken, Zouzou was in the throes of a full-blown heroin addiction. An incident recounted in her autobiography underlines her desire for anonymity. Unable to financially sustain her expensive drug habit, Zouzou and her boyfriend set out to rob a drug dealer. That night, one of her films happens to be playing on French television, and the dealer recognizes her. A mutual friend intervenes, and things are arranged without incident.

Later that year, she leaves France for St. Bart’s in the Caribbean for a self-imposed exile that will last seven years.

–Hedi El Kholti

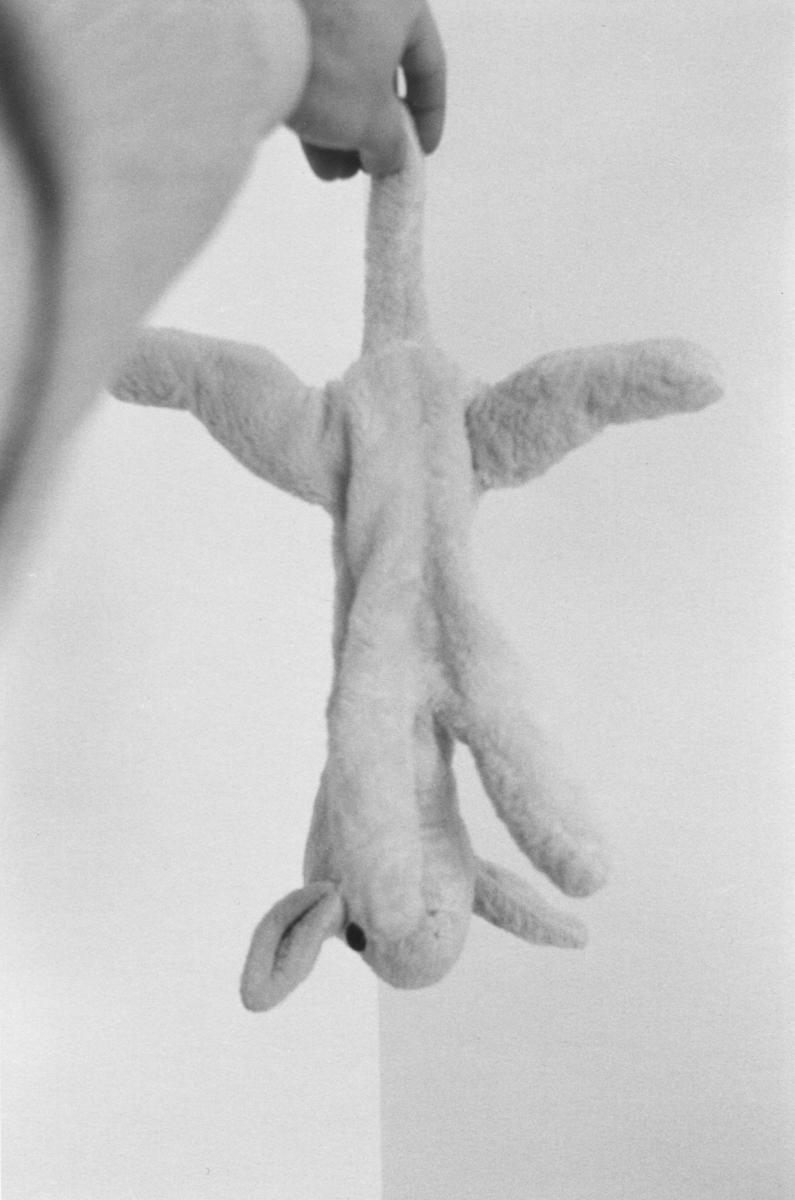

Agneaudoux

To understand photography as a way of representing what has died as wanting to be alive recasts the spectator’s wish for the return of the loved and lost or for the loved and lost to wish to return as the “want” of the photograph. It is also to reconceive the spectator’s encounter with the photograph as not a means of getting close to death but rather a kind of mad, even hallucinatory means of holding the cord of the fantasy of a returned love one never has to lose…

-Jill Casid, “Pyrographies: Photography and the good death”

Following the death of Ellen Cantor, my best friend — a term she reciprocated with “my future wife” in an epistolary work — I acquired a photograph by Hervé Guibert because it reminded me of her. It’s called Agneaudoux (1981) — loose translation, “sweet lamb,” and is probably a reference to the phrase “as gentle as a lamb.” I laughed — I laugh — because the irony of Guibert’s title also reminded me of her. Agneaudoux is a photograph of a small stuffed animal being held at arm’s length by the tail, its legs splayed and suspended upside down. Its charm is tinged with the permanent sadness of “wanting to be alive.” My friend’s work often involved imagining what it would be like if the “lifeless” characters of childhood grew up to have real adult lives. I liken Guibert’s stuffed animal to The Velveteen Rabbit, even if it’s a lamb — a little sacrificial, in the cinematic sense, its purpose being to die.

As affecting as I found seeing Guibert’s photographs in a gallery for the first time, my understanding of them is rooted in artist and theorist Jill Casid’s queer theory of “pyrography.” Her astounding essay “Pyrographies: Photography and the good death” is a close reading of Guibert’s photo-novel Suzanne and Louise through the writings of his friends — namely, Michel Foucault’s “The Social Triumph of the Sexual Will” and Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida and Mourning Diary. Casid teases out connections between photography’s unstable material qualities and its inextricable associations with mourning and death. By unwriting past-tense entanglements of loved ones and their pyres, she elegantly considers “what it means to use photography as a performative rehearsal for the catastrophe that has already happened.”

Casid posits the photography as the practice “of making volatile structures for feeling… in which one might begin to imagine and transact with care the losses and the letting go yet to come.” Throughout his life, Guibert was haunted by the specter of death. In a bid to draw it closer to him or push it away, he would experiment with it aesthetically: Suzanne and Louise is populated by staged simulacrums of his great-aunt’s deaths; at one point, he asked Barthes if he could photograph his ailing mother. In Casid’s discussion of these realized and unrealized works, impossible photographs that can’t or shouldn’t be made, she also speaks about love, mirrors, resequenced time, and the untimely. A note handwritten by Guibert that appears in the penultimate section of Suzanne and Louise reads, “A simulacra.” Here is Guibert’s photography as a “séance to the future.” I was told that if the kid in The Velveteen Rabbit loved his stuffed animal enough, it would become real. Maybe that’s why I like photography.

When my friend made an artwork from a photographed journal page describing me as her new mother and future wife, I felt the blush of exposure. She was omnilaterally in love with the world. It was a little embarrassing, this love. Thinking through the linkages between queer shame and narcissism, self-love and promiscuous affinities, in Eve Sedgwick’s Touching Feeling, Casid goes on to lovingly describe “the strange time-space of the photograph… as a kind of performance space and event, tantalizing with the promise of the narcissism of returned reflection and burning us with the shame of refusal. The queer stage or scene of the photographic contact [contract].”

In his love letter to his aunt Suzanne, Guibert writes, “When you feel yourself about to die, call me…” Like Guibert, my future wife photographed handwritten inscriptions and printed them in her published art books. Notes like “I hope you are well. Let’s be in touch soon” or “I miss you” appear on the back covers. What is given back, promised, and at times left unrequited is “transacted through the book or photograph.” Agneaudoux, like Guibert’s never-taken picture of Barthes’s mother, is unanswered love at its most resolute — a want, which is maybe just a failing to be alive. Or else a want that never dies.

For Ellen Cantor

–Lia Gangitano