London

Yto Barrada: Mobilier Urbain

Pace Gallery

May 24–July 14, 2012

In the final room of Yto Barrada’s first London solo exhibition, a small book rests unassumingly on a table. Clothbound, undated, A Guide to Trees for Governors and Gardeners presents itself as a historical primer in sprucing up — or, given the tree it advocates using, palming up — Tangier in anticipation of official visits. Self-described as “humbly submitted by a concerned citizen,” the Guide turns out to be thoroughly Machiavellian. Reduce labor costs by hiring from prisons and a large pool of the unemployed and desperate, it advises. Don’t waste resources on cleaning up back-streets, and, in order to impress visiting kings and dignitaries, transplant full-grown palms along all ceremonial routes.

The room in which the book sits is hung with large C-prints of quite another Morocco, taken between 2002 and 2011, the images variously sour, indicting, and wistful: old-growth forests, disintegrating restaurants, a fragile tree-house sanctuary in a strangler fig tree, a “disused survey site for a Morocco-Spain connection,” the historical holdout against colonialism that is the Rif mountains. Perhaps it’s not necessary to be aware of the Paris-born, Tangier-based Barrada’s avowed admiration for Jonathan Swift to see the Guide as her own Modest Proposal. Or to recognize that the vexed, saddened, never resigned Mobilier Urbain — for whose structure her book was the starting point and which, elsewhere, restrainedly fuses the traditional exhibition format with aspects of theatrical mise-en-scéne that echo the propositional Décors of Marcel Broodthaers — is spoken in the same voice.

The palm, nonnative to Morocco, is the show’s leitmotif: “a symbol of wealth, elegance, fertility, exoticism, and order,” as the book says — introduced in the early twentieth century for transformative purposes, standing for changes made in the present. A lollipop-like graphic of the tree, rising in thin regiments, adorns omnipresent colored wallpaper. Any cracks have been papered over, the visiting dignitary (or tourist) is you, and facing you as you walk into the first main room is a pair of near life-size palm trees — although these trees, in the sardonic form of Twin Palm Island (2012), are made of galvanized sheet metal, covered with illuminated colored lightbulbs, and emphatically mobile, sat upon wheeled trays: nature turned garish, fake, cynically instrumentalized, and recalling hotel lights (hotel building being big business in Tangier now). In the next room, following the Guide’s advice that it “is highly recommended to create a tabletop model on the scale of a children’s train set, showing the route of the motorcade and the placement of all elements,” is Gran Royal Turismo (2003), which is exactly that. As a motorized three-car motorcade trundles around a circular track through a miniaturized landscape, palm trees pop out of holes in the ground, the dirty facades of buildings spin around and are replaced by clean ones, street lamps go on, and Moroccan flags blow stiffly in the wind. Once the cars have passed through this Potemkin set, everything reverses.

The sociological backdrop — that vested interests are unmaking and remaking Morocco for tourism at the cost of anything indigenous — would be downbeat enough, but the defining plaint of Barrada’s art is that the traffic is one-way. Testament to this, facing Gran Royal Turismo is a quartet of photographs, Autocar (2004): oblique evidence of a less classy convoy. They initially look like abstract graphics on white backgrounds: green and yellow triangles, a stack of variously blue lines. Only the last one, an orange indicator light in its lower-left corner, makes plain that these are designs on vehicles. The patterns are ideograms of a sort, known by children and teens who stow themselves in the undercarriages of tourist buses in attempts to cross the Strait of Gibraltar, aiming — with a high failure rate — to subvert the massive restrictions on passage from North Africa to Europe.

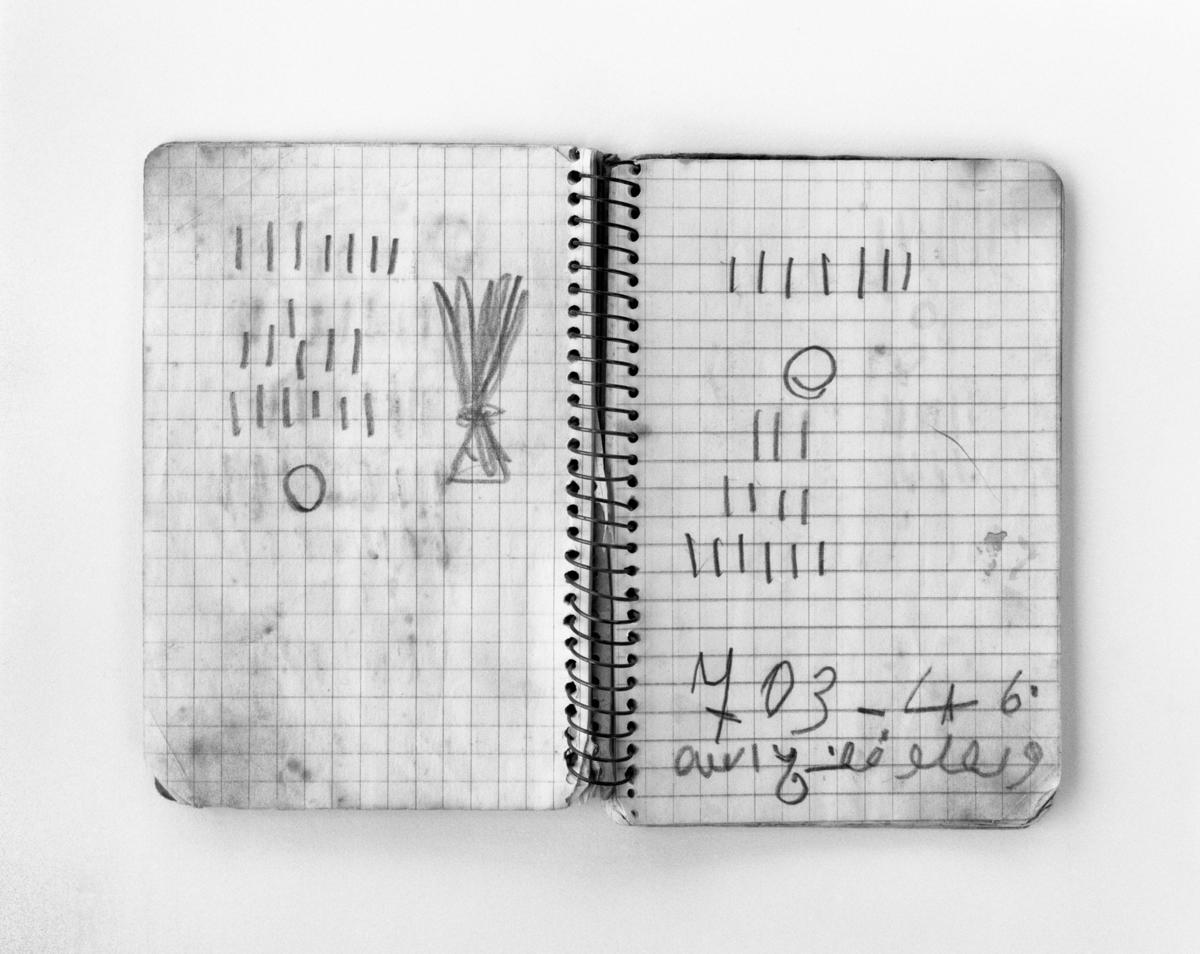

Barrada, indeed, establishes at the outset of her show that her work is multifariously concerned with the gap between appearance and reality, that the symbolic can be used by both the dominant and the dominated. On the walls across from the metal palm trees is The Telephone Books (or The Recipe Books) (2010), a touching testament to human ingenuity: its ten large C-prints document the notebooks that Barrada’s illiterate grandmother kept to record her various children and grandchildren’s phone numbers, a system of lines and images that would summon up each family member (circles for spectacles, and so on). Barrada’s work, whether approaching the speedy modernization of Tangier or the clandestine operations of its people, is attentive to what lies behind and beneath: understanding it is an analogous process of decocting its densities, cracking its codes.

Once one has done so, the power of Mobilier Urbain resides in Barrada’s sardonic counterpointing layout, constantly arranging showdowns between how vested interests envisage Tangier and the daily operations of its populace. (One can hardly complain, incidentally, if this is only an establishing sampling of her work, since the lengthily touring survey Riffs offers the larger experience, including her films.) What thrums through the show mostly doesn’t come from any one image but sparks intangibly between them, between the embodied language of power and the embodied language of resistance, claim and counter-claim. There’s only one person pictured in the whole exhibition, a child of indeterminate gender in the slow heartbreaker of a photograph Libellule blue (Blue Dragonfly) (Aeshna Cyanea) (2009/11), who raptly observes a big, iridescent insect. Both, under the circumstances, appear threatened — one by decreasing biodiversity in a country remade for moneyed guests, the other by narrowing options. Dragonflies, we’re invited to extrapolate, are on their way out of Tangier and this kid — wearing, not coincidentally, a Moroccan tourist T-shirt — probably isn’t, though he or she may someday be learning the colorful cryptography on the sides of buses. It takes a special situation for such a dismaying thought to also feel like a hopeful one.