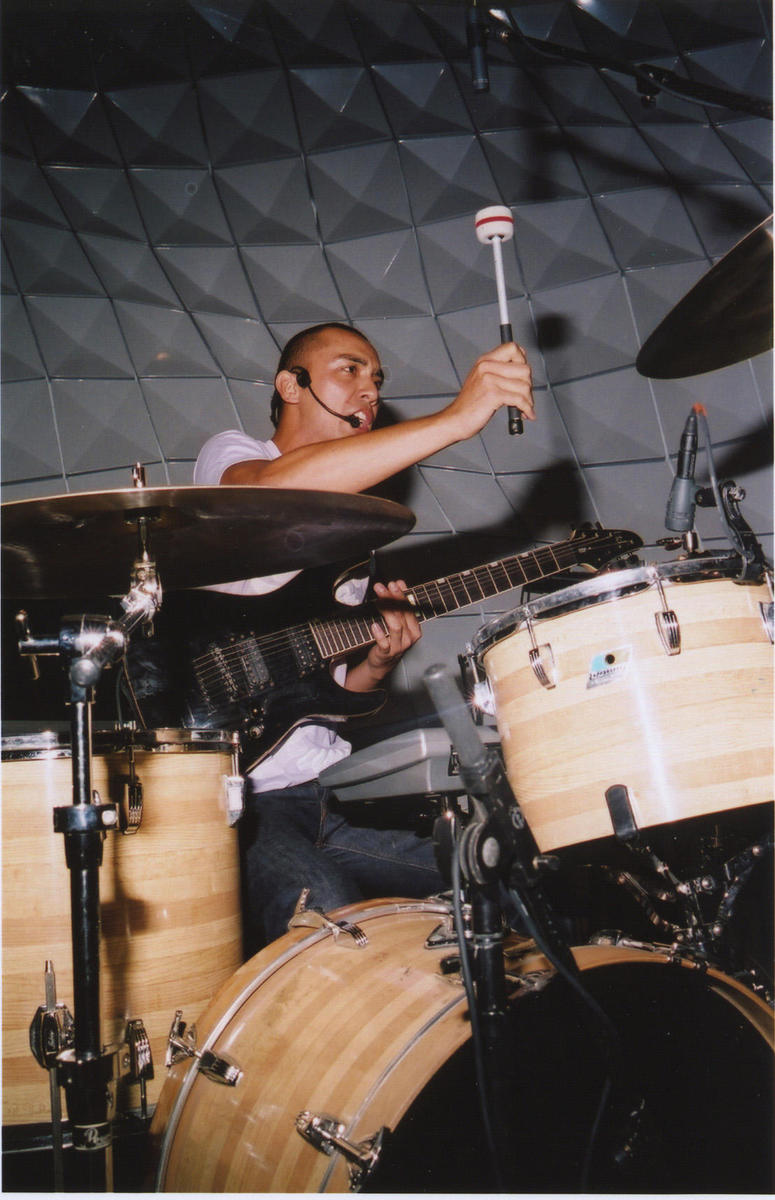

Hisham Bharoocha is a sonic citizen of the world. No sound, rhythm, or volume is too foreign, abstruse, or loud to keep him from digging into it, looking for the common human denominators of hope and joy. He boils down death metal, minimal techno, West African ritual drumming, and Hindustani classical music — among other ingredients — into a potent tonic he peddles as Soft Circle, a one-man trance band in a solo mystical medicine show. With a drum set, a seven-string guitar, a pile of pedals and a headset microphone strapped across his shaven dome, Hisham beats and bleats out mashed-up theme music for an enlightened cosmopolity with one foot on the dance floor and the other in Nirvana. Formerly a member of both Lightning Bolt and Black Dice, Hisham is currently working on a new album with his group Pixel Tan, playing shows with the acoustic trance trio USUN, and making new work for group art shows in San Francisco (Yerba Buena) and New York (Deitch Projects).

Nathan Salsburg: What are we doing? Why is Bidoun interested in you?

Hisham Bharoocha: Probably because I come from a background with a similar experience in western culture — people who aren’t central figures in the culture but who are in a position to influence or add an interesting element to it.

NS: Do you feel like you present yourself differently than other people making art or music in New York, or in the United States?

HB: People have their own logic, but there’s always a reason for it, and in trying to appreciate where people come from you can understand yourself and the way the world works a lot better. A lot of Americans, and especially a lot of people in New York, seem resistant before they even hear or look at or feel something. I concentrate on not having that resistance, on listening before I formulate an opinion. Some New Yorkers I’m around are always looking to find something they don’t like instead of something they like. Why would you put yourself through the misery of disliking something? It’s a defense mechanism. I do that also — I’m human, too — but I try to avoid it as much as possible.

NS: But you tend to negotiate all kinds of cultural realities. Your musical and artistic influences are from all over the place: Japan, California surfer culture, weird upstate New York meditation shit (laughter). Is that expansiveness something you’ve cultivated?

HB: Growing up, I listened to Top 40 and Michael Jackson, but my mother was really New Agey at the time, and would listen to kitaro at home, blast it so loud, the same thing every day. She had a Native American guitar cassette that I was obsessed with. When you’re a child, the only question is whether you enjoy an experience, and I was lucky to always have something to enjoy. My dad died of cancer when I was young, so I got really into thinking about why we live this certain amount of time, what our goals should be, and what the best way to enjoy your life is. Yet I totally love pop culture; it’s so fascinating. Pop music is a great place to see what kinds of recipes people have come up with for dealing with contemporary existence, for seeing how people get out of their heads and try to enjoy things. Producers in alternative rock, like the Matrix, or in hip hop, with the Neptunes — they know the chemistry, what can be absorbed into people’s minds most easily.

NS: Aren’t folks always trying to find a way to make something that’s both contemporary and transcendent? Consider how people are turning again to hippie culture, or psychedelia, or folk music. You know your influences in a much less self-conscious way than a lot of folks; you’re not just forcing two sounds or styles or traditions together to somehow legitimize what you do. What about your interest in traditional music? You seem to have pop music on one end of your spectrum and African ritual drumming on another…

HB: Or metal.

NS: Yeah. Metal.

HB: When I’m observing the way my mind reacts to certain types of music, or the way it makes me feel physically, it seems like I’m always going for the same thing, which is to really enjoy the experience. If I listen to this (Vishwa Mohan Bhatt is playing in the background), I get a feeling of being home. I feel the same way when I listen to death metal. It’s so rad to imagine these kids trying to come up with the most brutal riff they can think of and for me the comparison between metal and Indian classical music is obvious. It’s a drone so intense that it puts you into a trance state where your mind becomes less linear. I look for the same thing in pop music, like a really good loop in a hip hop song that you want to hear again and again. That’s when you know it’s working.

NS: That’s the transcendent moment, right? We expect everything to be progressive, but a drone doesn’t take you anywhere. It just is, over and over again. That explains the description you give to your other band that no one has heard yet, Colossal Caves — you call it “life metal.”

HB: Yeah, that’s from my childhood desire to be in a metal band, concentrating on the drone of metal that gets you in a really excited, entranced, adrenaline-rush sort of state. It’s just really fun–– it’s like home sweet home. I want to make Colossal Caves an art project. Conceptually it involves this drone, but it’s also a humorous reference to what death metal kids take so seriously. Colossal Caves will be costume-based. A big part of music is performing, and I want to embrace all the beauty in all those stupid poses you do when you’re playing. It’s funny to look at all the parallels sometimes, why certain things relate to others.

NS: Soft Circle is a good example of that. You’ll finish some super heavy song, all heavy drumming and singing and guitar, and right away say some goofy thing to the audience, and it catches people off guard. It’s good, it’s disarming.

And with Black Dice — you laid an organic, rhythmic element underneath an assault of noise. You made it much more accessible for a lot of people, like me.

HB: That’s such a key element in making something experimental. You can make your most conceptual visual art or music and if there’s nothing that anybody can latch onto, then who are you trying to communicate to? I don’t want to communicate only with a very limited audience with a very specif ic education and the experience to understand what I’m doing. If you’re going to fight the battle, you have to look at who you’re fighting it for. Like in punk rock, there’s the visceral experience of rocking out (laughter) that makes the kids intrigued. I like being the conductor. I grew up playing bass, and I like being the person who plays the trance-inducing part of the music.

NS: The organic part. It sounds like that was a big part of your interest in Vipassana meditation.

HB: Definitely. The concept of meditation — having an experience without extreme desire or attraction, or extreme aversion or fear––definitely influences my music. I got into meditation and yoga to keep a balance and to enjoy myself. I’m trying to fill my music with all the human elements, trying to be as thoughtful and humanitarian as possible. I’m just trying to communicate to people to be in your happiness and in your love and for everybody to get along on the planet! (laughter.)

NS: I feel like that adds a little unspoken political element to your music. Woody Guthrie said he was sick of music that beat you up and put you down, and that he wanted to make music that built you up and made you feel good about yourself. That’s not a kind of music that our culture puts a lot of stock in right now.

HB: There’s a lot of blues in hip hop, talking about the hard times. I relate to that because of where I am right now — I’m not able to pay for things easily or live a comfortable life, and I feel that struggle. That music gives hope to kids out there saying, “Fuck this, man, we’re gonna have a good time. We’re gonna get out of this — we’re gonna keep working hard to get out of this.” I like that element of motivation in music that comes from people who struggle — it’s the most charged music there is.