Damascus

The Seasons of Tell-Al Hejara

Almakan Arts Society

August 16-27, 2007

In the 1960s and 70s, Damascus hosted a constellation of innovative artists and intellectuals who gathered around the brilliant, prickly figure of Fateh Moudarres (a photograph of Moudarres, furrowed brow and all, still hangs in the studios of his students). Today, the city’s art scene is often overlooked — dismissed as retrograde by ostensibly more cosmopolitan artists in neighboring countries. Still, there are things happening. The recently opened Ayyam Gallery has been supplying Christie’s with a bounty of Syrian work, old and new. Aleppo has its own international photography festival. And one exhibition held this past summer, ‘The Seasons of Tell-Al Hejara,’ provided a rare glimpse into some of the more interesting work being produced in Syria, along with the conditions of production.

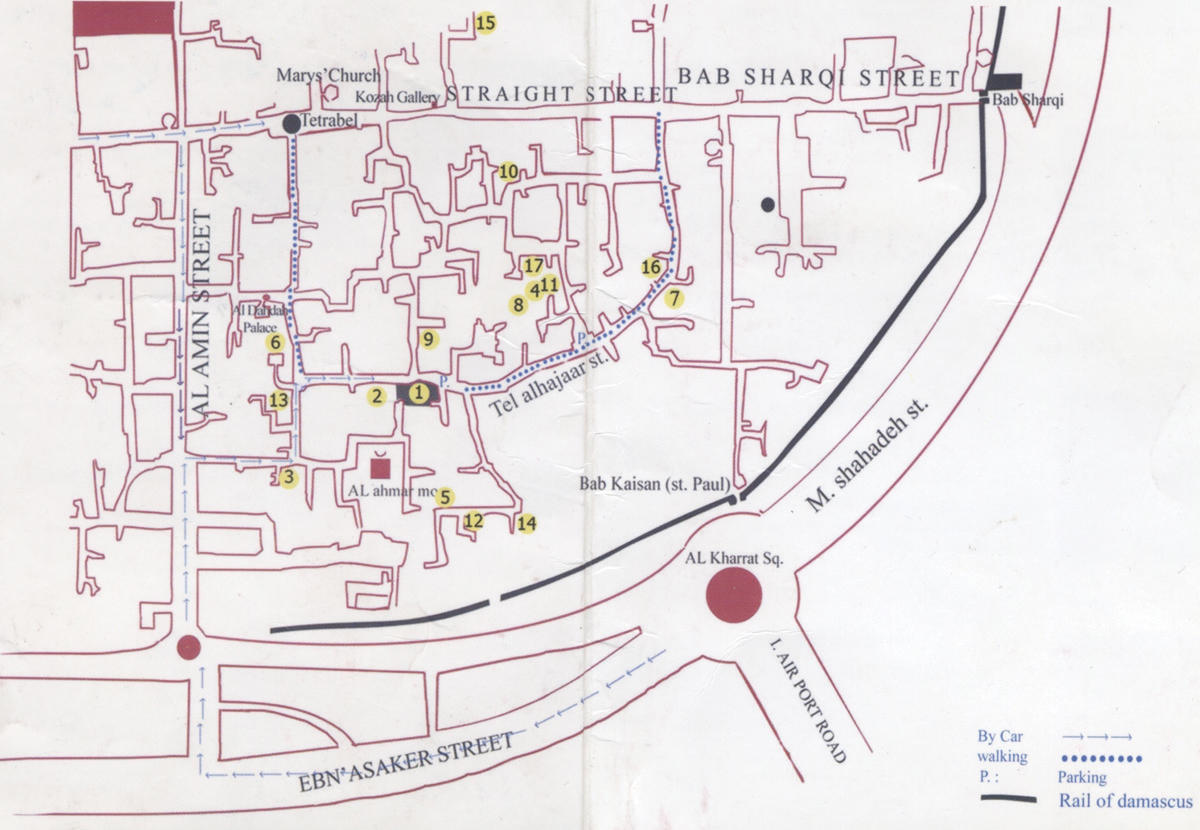

An epiphenomenal event organized by Mustafa Ali, Syria’s most famous living sculptor, ‘The Seasons’ opened with a group show at his atelier/NGO. Student paintings were hung side by side with those of modern masters. A plinth in the center of the room held an abundance of clay and metal works in various states of torque. The centerpiece of the evening, however, was the walking tour that followed. A mixed crowd of expat diplomat types, local arts lovers, and students followed Ali as he threaded through the dark streets, visiting the small artists’ enclave that exists within Damascus’s old city, an area once inhabited by the city’s Jewish families, then abandoned, and now undergoing gentrification. With Ali in the lead knocking on doors, the tour entered the work spaces of fourteen artists within one small footprint of dilapidated urban terrain. The hope was that visitors would engage these secret spaces over time and at their own pace; a timetable was circulated that indicated the days and times when one could make return visits.

One of the most valuable aspects of ‘The Seasons’ and its staging was the casual ease with which it treated private and public space, especially set against a framework for cultural production that is often tightly regulated by the state and the logic of “people’s palace” exhibition halls and registered artist associations. Inverting the usual trajectory of consciousness-raising art events, it moved from the street into the atelier, accessing and acknowledging a rich interior life for unassuming and seemingly unaffiliated artists.

Ali’s own sculptures suggested an iconographic program of epic proportions, solemnly reworking the 7,000 years of local artistic production Syrians profess as heritage, from the lumpy clay of Ugarit to Picasso’s riffs on the manuscript paintings of al-Wasiti, a medieval miniaturist. Although largely unsatisfying taken individually (lots of cages and primitive bestial forms) they did important work by stylizing the exhibition’s temporal structure, suggesting the archeological processes of excavation and sedimentation — those workhorse contingencies that make things interesting.

In another studio, Edward Shahda, a magical realist and admirer of icons and cultic compositions, was touching up some peculiar landscape views. The crowd milled around him. Sculptor and painter Fadi Yazigi displayed a new series of tabletop bronze figurines. Compact animal bodies bore overscale human craniums, sightless eyes, and archaic smiles. Such spooky objects introduced a sphinx-like uneasiness into Yazigi’s usual delusional aesthetic, all grins and cartoon lines.

Also of note were Ghassan Nana’s paintings. These canvases were preternaturally beautiful. Displayed inside niches, the paintings featured gauzy oil glazes that built up the suggestion of women standing in Early Renaissance-like groups. Nana’s studio, as pristine and quiet as a church, heightened the theatrics of trespassing already inherent to the tour format. Every image in the room was acutely moving. I don’t want to pretend — much of the art in these neighborhood studios felt anachronistic.

For one, artistic strategies like interventions and relational aesthetics aren’t necessarily compelling in this life, in this old city. An element of irony was missing in the assembled works, a deficiency that Clement Greenberg (an anachronistic choice of a theorist) might help to explain. Marshalling his faith in avant-gardism as a force against kitsch and fascism in the 1930s, Greenberg wrote that “Stalinists” have a problem with the avant garde not because avant garde work is too critical, but because it is too innocent. It is too difficult to corrupt by injecting it with propaganda; it cannot be used for anything but its own ends. The overriding formalist aesthetic at ‘Tell-Al Hejara’ may have come from this need for integrity; its honor certainly remained intact (even as it started to look a bit kitschy). The art was one part inoculation against decades of image-based propaganda and one part assimilation of a Syrian socialism that is ill at ease with signs of chummy relations between art and commerce.

The best work on view was a camel’s head sculpture by Nour Aslia, on display in the group exhibition at Ali’s studio. Hung in the corner, it looked like an old, desiccated cow pie. It was totally abject: great lumps of plaster, patted into form and coated with a rusty cinnabar pigment, which was rubbed and abraded from the crevices of the material. Such formal carelessness is not the way fine art tends to work in Syria. But the artist — a young unknown — went for it, and that made everything feel right.

www.mustafali.com