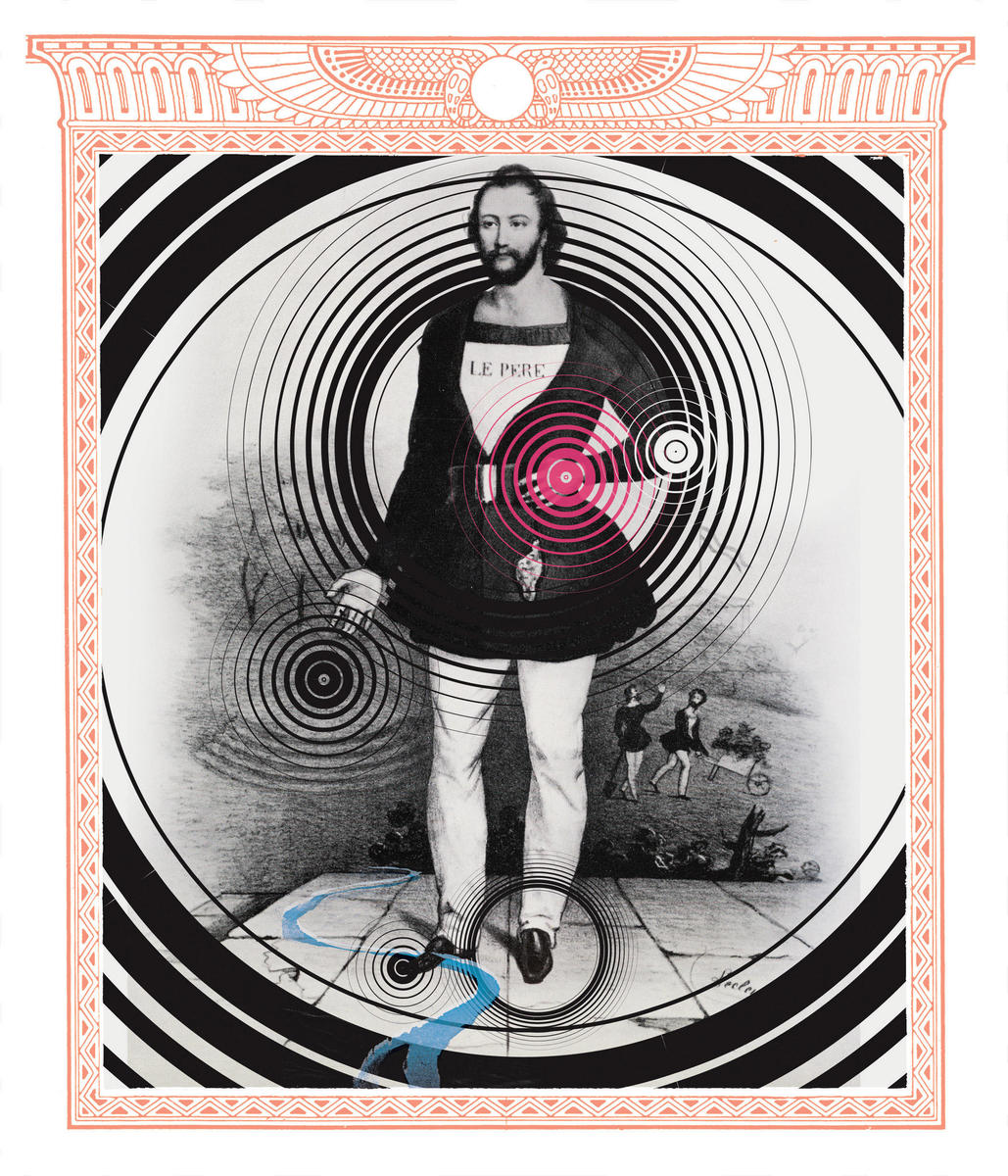

In late August of 1832, one trial offered Paris a striking spectacle: the defendants, who obliquely referred to themselves as the Saint-Simonians, entered a crowded court room wearing brightly colored costumes and chanting hymns of brotherhood and love. The unlikely group was to stand trial on charges of violating “public morality and good manners.”

Articles published in their organ, the Globe, by Père Enfantin, the spiritual father of the family, had outlined the Saint-Simonians’ scandalous ideas on the relations between men and women. Enfantin had prophesied that the “tyranny of marriage” would soon be replaced by “free love.” He further shocked the court by insisting on having his case defended by two female lawyers. Unimpressed by this, and by their call for a new “religion of humanity,” the magistrate found them guilty. The group was officially disbanded, with its leading members, including Enfantin and Michel Chevalier, the editor of the Globe, sentenced to six months’ imprisonment.

While in prison, Enfantin dreamt of the East. There, he — le Père — would ostensibly find a female messiah — la Mère — and together they would proclaim the new moral order and take their place as heads of the world family. Joining Orient with Occident, man with woman, rich with poor, he laid out his vision of utopia. And for Enfantin the road to that blissful future led directly to the Suez Canal, of all places. “It is we who will make between antique Egypt and ancient Judea,” he wrote, “one of the new routes of Europe toward India and China… We will thus place one foot on the Nile, the other on Jerusalem; our right hand will extend toward Mecca, our left arm will cover Rome and rest against Paris. Suez is the center of our life of labor; there, we will make the act that the world awaits, the confession that we are Men.”

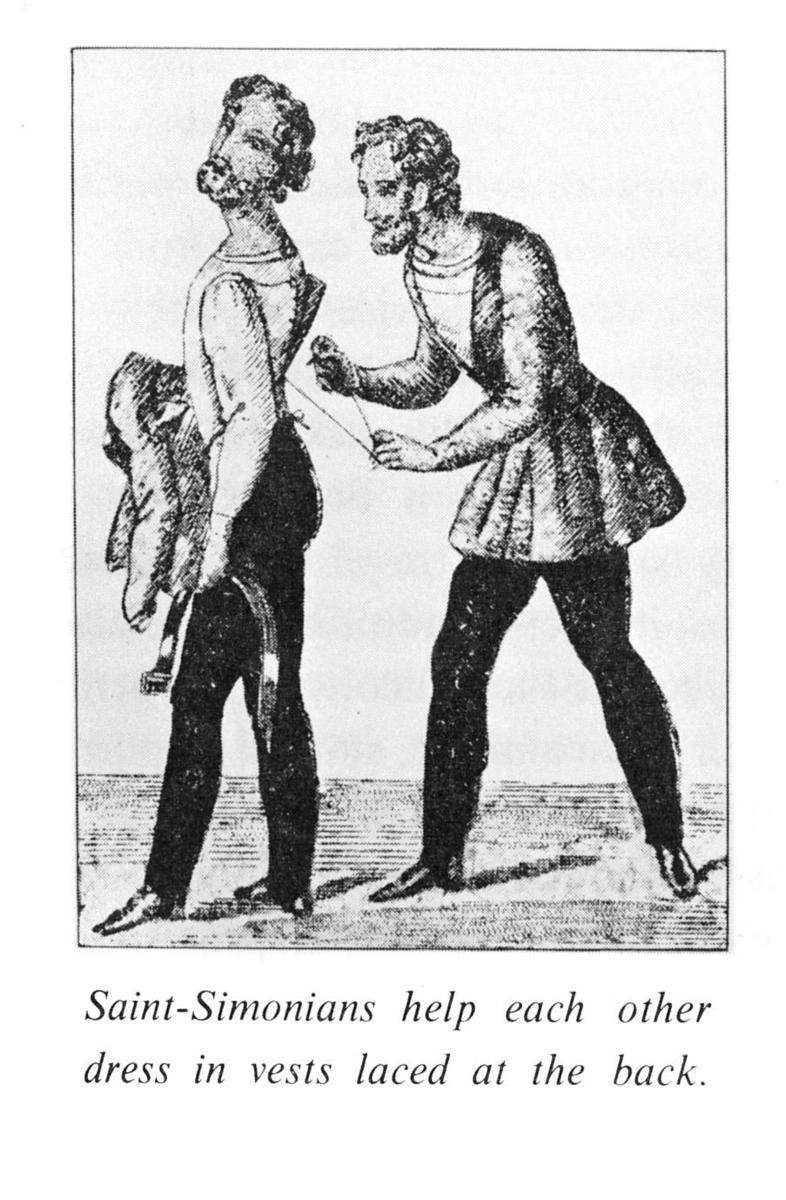

The Saint-Simonians would attract hundreds, if not thousands, of followers and spectators during their escapades. Prior to their trial, they had built a temple in their camp at Ménilmontant, what was then a suburban commune outside of Paris. There they would perform their rituals, complete with costumes, marches, chants, and feasts, before crowds of curious onlookers. They took to wearing collarless shirts, flowing red scarves, and long blue coats that buttoned on the back (to foster a sense of dependency on their brethren, in dressing as in other aspects of life). A beard was de rigeur.

The Saint-Simonians’ eccentricity was matched by their inconsistency: sons of the bourgeoisie, they appealed to workers but never called for a revolution of the proletariat, and while they were outspoken advocates of free love and what they termed the “rehabilitation of the flesh,” they took to making frequent vows of celibacy.

Incongruous though it may seem, this strange mystical sect also pioneered rather modern-sounding ideas of globalization and technological progress. The Saint-Simonians had emerged from post-Revolutionary Paris to proclaim a new philosophy of humanity: a religion of brotherhood ruled by a new technocratic class, the spiritual leaders of a global future that would merge industry, banking, and technology. Disciples of Comte Henri de Saint-Simon, the well-known early socialist and ardent positivist, and the proponent of a “New Christianity,” these visionaries took the philosophy of their master into uncharted territory.

After the trials, Père Enfantin and his followers embarked on a voyage across the Mediterranean, going first to Egypt and then to Algeria, to realize their utopia in the Mediterranean basin. It was there that they executed a number of their first large-scale engineering projects, including several Nile barrages, canals, and polytechnics. Much like the globalization gurus of today, the Saint-Simonians called for greater cross-border transactions, more rapid international capital flow, and the diffusion of technology and technological expertise. They helped finance and build railways and canals, constructed global communications and financial networks, and contributed crucially to the growing nineteenth century fascination with technological progress. And, as we shall see, they offer those who look to history a lesson in the unexpected consequences of technological utopianism.

The Saint-Simonians’ stay in Egypt was short-lived. Disease and the failure to find his female messiah led Enfantin back to Paris in 1836, after just three years. Nevertheless, he and his followers — including Ismaïl Urbain, a convert to Islam, and Suzanne Volquin, a journalist and early French feminist, had been instrumental in realizing a number of significant works in engineering and public instruction. Their example equally inspired Mehmet Ali, the Albanian-born viceroy of Egypt under the Ottomans (often considered the founder of modern Egypt); he eventually constructed large-scale public works and generated a body of newly educated technocrats to man the extraordinary modernization of the state.

The Saint-Simonians had had high hopes for their collaboration with Mehmet Ali, whom they termed the Pacha industriel. Yet they failed to convince him of the viability or virtues of their pet project — a canal at Suez. It was not until a generation later that Ferdinand de Lesseps would manage to convince first Mummad Said Pasha and then Khedive Isma’il to undertake the scheme. Mehmet Ali had been much more concerned with constructing a system of barrages along the Nile, a task several Saint-Simonian engineers began in 1834. Others went on to found various schools and polytechnics, including an infantry school in Damiette, an artillery school in Thoura, and a cavalry school in Giza.

Enfantin returned to Paris in 1836. Some of his followers remained in Egypt; others traveled to Greece, Turkey, East Africa, and Mexico. They conducted scientific and geographical expeditions, aided in the financing of railroads, and oversaw a number of public works, including hospitals and schools. A few years later Enfantin was invited to join the Scientific Commission for the Colonization of Algeria and left for Algiers in December of 1839. Enfantin’s later published study — La colonisation de l’Algérie — was a curious blend of technocratic idealism, racial social science, and economic, industrial, and urban planning proposals. In it, he argued that a rational and centrally managed economic structure — his appeal here was largely to bankers and not to landowners — needed to be put in place in order to serve the goals of a mutually beneficial colonial “association” between France and Algeria — greater industrialization, social reform, and the migration of peoples and goods and skills and services.

Upon his return to France, Enfantin created a Society for the Promotion of the Suez Canal. He continued to hold on to his earlier vision of the bridging of East and West. Indeed, the building of a canal at Suez symbolized the same thing for many generations of French technocrats in Egypt: Napoleon Bonaparte’s own savants had conducted measurements and cadastres for a canal in 1798; the Comte de Saint-Simon had seen the building of canals at Panama and Suez as a means of uniting the world through technology and finance. Enfantin’s lobbying efforts soon bore fruit. Indeed, although de Lesseps never publicly acknowledged his indebtedness to them, his schemes for Suez were much inspired by the Saint-Simonians. (He even used their calculations.)

Yet when the canal itself opened in 1869 with much pomp and circumstance — to the strains of Verdi and underwritten by the nearly bankrupt coffers of the Khedive — it marked not the start of a mutually beneficial association between East and West, as Enfantin had envisioned it, but rather, the beginnings of a new European imperialism in the Middle East and the “scramble for Africa.” As we have since witnessed, the canal has proven to be a key political pawn in the hands of nineteenth and twentieth century superpowers; power struggles over the control of the canal have led to occupation and then to decolonization, to the Suez crisis and the beginning of the Cold War order in the Middle East. Indeed while the Saint-Simonians had been almost entirely optimistic in their vision of the power of good inherent in technological progress, in a post-Cold War and atomic world, this optimism has become more than a little tarnished.