At first, it was contained, it had borders, like the square of the canvas or page. One night, I moved the tables and chairs to the bathroom, and I didn’t think much of it, I thought that at most I was birthing a new cleaning ritual. The week went by like this, and I still did not know why the living room was empty. I was acting on pure instinct.

I went to Home Depot and spent a lot of money there. I didn’t know why or on what or how. I was driven by something stubborn and aggressive, and by the time I realized what I was doing it was already too late. When I came home with all of the supplies it was all the same, not a moment of hesitation. I walked around the perimeter of the room with a pencil, tracing my height on the walls. Everything above that line I painted blue, a light blue, the color of sky. Blue, in general, is a simple color, that is why it’s so calming. Below the line, I painted the wall the color of sand. When I felt that it was beginning to dry, I started playing with it, with my palms, my feet, I gave it some texture. Then I nailed wooden lattices, which I had painted green, the color of the leaf of a lemon tree, on top of the sand. The exterior wall, the one facing Fulton Street and the bus stop, was the strategic border. I covered the windows with barbed wire and draped some torn plastic bags on top, as if they had been blown by the wind.

There was no bathroom. The bathroom is where it all started so I boarded it up. With wood and nails and a paper that said, STAY HOME TO SAVE LIVES.

In the center of the empty room I had, somehow, I can’t remember the details, erected a big mound of dirt. It was made up of potting soil, white sand, organic fertilizer, red and green clay, cumin, cinnamon, and gravel.

If I had been thinking about what I was doing, then the thought of having to clean up would have been enough to turn me away. For months I had tried to get a grip on things, control my surroundings and body. I was tired of shaving, I was tired of cleaning, I was tired of sanity. But I did not accept defeat. I kept adapting. Even at my lowest point, having realized that my strategy to impose order had failed bitterly, because one cannot fight against time, or the city, I had morphed again and invented a new way forward.

The project was to create a new natural order. The idea had come to me from a greenhouse in Paris, where I found all the fruits and vegetables one can dream of, a miniature Eden at the center of the city. That, and the wilderness of upstate New York. But I understood that what I needed was different, something older, a regression to my biblical homeland.

We were not farmers, my family was of the urban elite. In fact, my great-grandfather was a wealthy landowner. In 1948, the falahin who were working his fields became refugees and Israel confiscated all his land. He went from rich to poor and died of heartache in front of my grandmother. So what I know about nature, I know from her garden. Herbs, citrus, nuts, those wonderful fruits whose names probably don’t exist in English.

One is like a pear-shaped apricot, with the thick skin of a grape that you want to peel with your front teeth, its insides wet and fragrant, with four elongated smooth seeds at the center, sensual like crystals but each encased in an edible placenta. One is like a blueberry grape but sour, it grew on the bush next to the lily pond. And one is the size of an apricot, the color and skin of a Honeycrisp apple, and the crunch of a raw green almond. The flavor perhaps a combination.

The fruit belongs to the land, not even to my grandmother. You have to remember that she was demented by the end, she ate them without knowing their name, or her own.

Me, I don’t have a name. I lost it in battle, like the knight who lost his shield.

I installed with abandon, working from the bedroom, which was now the workshop. There was barbed wire, wild thyme, crates of citrus fruit, bags of dirt, duct tape, linoleum, wood and nails for the cross, a glue gun, a humidifier, a fan, and UV lights. Some things I bought and others I collected. I went to Fort Greene Park and collected stones. I climbed into the locked park across the street and uprooted one small tree and one bush, dragging them back to my apartment, and went briefly to the school where I worked to get the two goldfish, Beauty and Justice, from the aquarium in my classroom. I even went to Whole Foods, for persimmons.

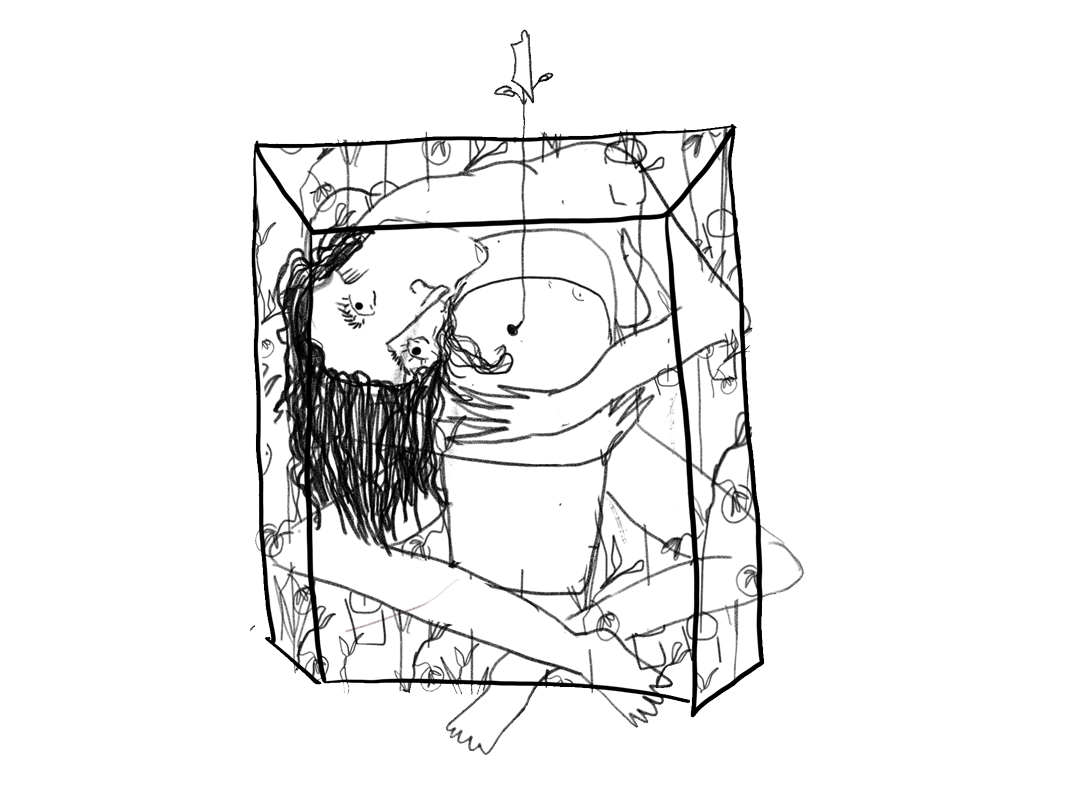

The landscaping was based on my plants that had survived winter. I pushed the pile of dirt and spread it around. Layering, layering, layering. I must have lost thirty centimeters of my ceiling height. I planted the aloe vera at the center, the five vines in the kitchen, which I had covered in a camouflage wallpaper, not in dry browns like the American army, but deep greens like cypress trees. I placed the spider plants next to my bed, an herb garden by the windows, the ferns at the entrance of the land, the climbing plants around the wooden lattices and barbed wire. The remaining cacti I placed in a row, creating a new floor plan in the room, separating the sleeping area, which was the blue yoga mat, from the recreational area, which was a kiddie pool in the sunny square. I filled it with water, lilies, Beauty and Justice, and a fifteen-year-old koi I purchased in Chinatown.

For the bathroom, I made myself a litter box, a bucket that I painted with flowers and suns in acrylic pastels. I planted a lavender next to it, fragrant and serene. If I needed to go to the bathroom, I used one of my white towels, of which I had six in total, in different sizes. I would put a towel in the bucket, and after I finished, I layered it over with another towel. When the bucket was full, at the end of the day, I dumped it all in the washing machine. I would run it once, on thirty. A second time, on sixty and with detergent. A third time, on ninety and with detergent and bleach. You wouldn’t believe it, but the towels came out clean. I was giving up a lot of my old habits, I was giving up on the comforts of modernity, even on my clothes. But I was too attached to doing laundry, and I continued doing it, I just did it differently, I did it harder.

When I was little, I had a Jewish friend, a very gentle girl who dreamed of becoming a ballerina. She lived in a beautiful house with thick stone walls, arched windows, and a lush garden. It was the house of a Palestinian family that had been expelled in 1948, and her father was born there, a few years after the cleansing. I used to go over to her house in the afternoons, and I loved it, I loved her family too, although she was an only child and there was something sad about how quiet the house always was, with classical music playing softly in the background.

Her mother would make us pasta with béchamel sauce, two small bowls and two small spoons, their lifestyle and demeanor very minimal. I remember asking my mother to make me béchamel but she couldn’t figure it out, she didn’t have the patience for it.

I loved my friend’s house but I knew that it was haunted. Even at a young age, I knew that there was a family out there in the world that was still holding on to the key. No, I didn’t know this intuitively. Each time my mom picked me up from the house she made a remark about it. Of course, the door had long been changed, it was a modern glass door with a keyhole fitting a small aluminum key, which my friend kept on a friendship bracelet. I remember that above the door they had garlic cloves hanging. My friend told me that it was there to ward off vampires, but I think it was to keep the spirit of the original inhabitants away.

We spent a lot of time in the garden, playing hopscotch, finding sticks, and one time we even tried building a tree house on the walnut tree. We climbed the stone wall to nail some planks into the tree, and a piece of the wall crumbled and fell on my friend’s precious ballerina foot. Her mom panicked, she thought her daughter would never dance again, and she yelled at the father that they needed to renovate the house, it was over one hundred years old.

Sometime after that, I came to her house, but we were no longer allowed in the garden, so we played with her Polly Pocket. My friend said she had a secret, but I couldn’t tell anyone. She told me that when the workers dug in the garden, they found two underground rooms. The first room, she told me, used to be the old toilet of the house, before there was sewage. It was the poop room, but it didn’t smell bad anymore. Inside the poop room was a secret door, which was locked. Her father told the workers to leave. At night her parents went in there, they opened the secret door. It led to another chamber, at its center a big wooden chest full of treasures and gold.

I never spoke to her again. I never told my mom the story, but I was old enough to know right from wrong. My whole life, I kept thinking of that secret chamber off the shit room, the wooden chest inside, full of the silverware and gold of the family who thought they would return.

Before I came to New York, I was visiting my uncle, and one night I walked past that house, I’d felt magnetically pulled to it. I slowed down before reaching it. I couldn’t remember exactly where it was but I knew that I would recognize it when I saw it. From the darkness emerged my friend’s father, in pajamas and slippers, looking a hundred years old, no longer the agile young father who used to drive us around in the cute blue Polo. I said hello. It took him a moment, but he remembered me. I think he was happy to see me, but he looked deep in sorrow, in pain. We only exchanged a few words in the dark, he was shaking, said he had Parkinson’s.

No, my apartment wasn’t dirty. Nature is clean. It’s civilization that’s dirty.

The first few days were great, of course. The set was immaculate. I had acquired the healthiest, freshest flora. I spent long hours landscaping, deciding which plants got along, which didn’t. I took into consideration the light, the afternoon shadows. It was both an aesthetic and a pragmatic practice. I watered carefully, with my eyes closed, like I was rain. The result was magnificent, it was warm inside, twenty-five degrees Celsius, and the humidifier was working all day, with extracts of the sage and jasmine. The soundproofed windows were always fogged, bringing in soft light and none of the visual pollution.

I had a wonderful dream there, in my transformed apartment, or perhaps a memory. In this dream, I am lying on the couch, and my father is sitting on the armchair across from me. I am a child in the dream, watching TV. It’s a summer evening, the sun is setting slowly. I can hear my mom making noise in the kitchen and my brother must have been home too, in his room. I am watching an episode of Power Rangers and my dad is just sitting there, watching with me. The episode is very good, I watch it, enthralled, the yellow one was kidnapped and they were going to rescue her. My father and I talk a bit. He is the same age as when he died, the way I remember him, forty-three years old. He asks me how I’m feeling, if my ear is still hurting. I used to have a lot of ear infections as a child, I remember him dripping medicine into them, the salty liquid slipping into my mouth. It’s better, I say, resting my hand underneath my ear, watching the TV screen.

When I woke up, I could hear his voice, but after a few seconds I forgot it again. I expected my ear to be hurting, like in the dream, but it felt okay. I hadn’t left the apartment, in fact the living room, in a few days. My body, inside as well as outside, was warm and moist. I was doing just fine. I was still alive.

The days were getting longer, I watched the aloe vera plant grow so quickly that I sometimes wondered if it was thickening before my eyes or if my eyes were going into REM. The stalks were thick and juicy, I would snap them, carefully peel off the skin, and rub the wet flesh on my face. Sometimes I would grow impatient and just squeeze them between my fingers, my fists, until my hands were covered in the clear slime, which I would rub on my skin and hair. It sounds dirty but everything in there was mine. It was natural, I had chosen it.

I had experienced this raw physical energy before when dancing, or having sex, or sometimes even just stretching. But now, in the new natural order, I found a different purpose for my body, a rejection of how I had used it for so long. I could put my face in the dirt, or eat on all fours. I could lie on my back and wiggle my legs in the air, then point my vagina at the sunlight. I didn’t have a partner to play with, but I rediscovered my body’s arousal and could masturbate for hours instead of just rubbing my clit for five minutes to the forceful replaying of pornographic images in my head.

A lot of boundaries were now gone, and the compartmentalization of the body stopped making sense. There was no more head, shoulders, knees, and toes. And at the same time, I realized that I wasn’t going to morph into one mass. I could always undo the knot and stand up on my feet and assume the standing posture of the Homo sapiens.

I was one with myself but also separate. I understood that if I could control my body, move an arm, a leg, my tongue, then it meant that we were one, made of the same. But I couldn’t control it all, I couldn’t control the breathing, the heart, the will to live. Parts of me had their own desires, their own moods and needs, their own voices. It took me time to address them, in the beginning I was only comfortable with the obvious. When I was hungry, I asked my stomach, Baby, what do you want. And often it would say lentils, or rice, or occasionally cabbage, because the intestines were chiming in. Or if my heart was aching then I would ask, Baby, what’s missing. And it would say a man, a hug, a cry, an uncontrolled laughter. And I could make myself laugh, or I could make myself cry. If it wanted a hug, then I would hug myself, I would coil into a snake. And I couldn’t give it the man that it wanted but I could imagine, and I had some great memories I could call up.

Sometimes my ears or my nose or some other sense would make a request and I would give into it, very lovingly. I would sing along with the washing machine or smell a flower or eat it and try to smell it through my mouth. And eventually, I became more and more confident that this was a safe method of living, that it would be impossible for me to hurt myself this way. My body was harmless, it was not hostile, it wasn’t trying to kill me. We wanted the same things and were the same.

Adapted from The Coin (2024) by Yasmin Zaher. Courtesy of the author and Catapult

What is Palestinian literature? In After the Last Sky: Palestinian Lives (1986), the late Edward Said suggested that the Palestinian novel is characterized by a non-linearity that reflects the fragmentation of the Palestinian psyche in the aftermath of the Nakba. More recently, the critic Miryam Schellbach has applied Said’s theorem to the material conditions under which such literature is produced; any accounting of “Palestinian literature” has to account for the ever-increasing volume of languages in which Palestinian writers in the diaspora now write. Schellbach, a German-Palestinian, cites writers in Arabic and the colonial languages (French, English, Hebrew), as well as the Spanish-language novelist Lina Meruane, who hails from Chile, home to the largest Palestinian population outside the Middle East.

“The Garden” is adapted from The Coin, Yasmin Zaher’s exhilaratingly dark debut novel about a Palestinian emigree in New York City. Zaher is from Jerusalem, where she worked as a journalist for Haaretz and Agence France-Presse after completing her degrees in the US. She wrote The Coin, in English, after completing an MFA at the New School. Though the novel explores familiar exilic themes — trauma, alienation, class, and culture clash — Zaher upends the tropes of the classic immigrant tale. The narrative follows a young Palestinian woman and her eight-month experiment in New York, working as a teacher of underprivileged kids at an elite middle school in the city. Inspired by Ottessa Moshfegh’s irreverent protagonists and the fashion-forward ingénues of chick lit, Zaher’s neurotic narrator spends most of her free time ritualistically bleaching her apartment, grooming herself, and tending to her capsule wardrobe of rare designer items.

Despite her exacting routines, there is a picaresque quality to her existence. She makes excursions: to upstate New York with her soon-to-be ex-boyfriend, a Russian real-estate investor named Sasha; to Paris with her rebound, a dubious gay art dealer she calls Trenchcoat, whose side gig — smuggling Birkin bags to the US — she participates in for a time. Toward the end of the book, the protagonist, yearning for her grandmother’s garden in Jerusalem, attempts to create a Garden of Eden of her own within the confines of her Brooklyn apartment.

More than anything, I’m enchanted by Zaher’s offhandedly uncouth tone — a virtuosic vulgarity that erupts amid her sparse prose. (“I was becoming like the filthy and rich, a fishy pussy with a floral neck,” her nameless narrator observes one day, as her obsessive regimen of personal hygiene and self-care begin to break down.) The Coin is proof that the diasporic novel can be as chaotic and playful as a romantic comedy while remaining as claustrophobically introspective and deranged as anything by Sheila Heti — and all this, without sacrificing the tragedy and revolutionary possibility that defines minor literature.

—Aria Aber