The work of Los Angeles–based artist Nour Mobarak can be understood as an open-ended engagement with the promiscuous and constitutive power of words. Her polymathic art unfolds across performance, video, poetry, sculpture, and sound, with her own voice often serving as a through line.

As a teenager, Mobarak underwent seven years of classical voice training. Opera’s formalism wasn’t the end goal, and by the time she attended university in England, in the mid-2000s, she was playing in a nostalgia-tinged no-wave rock band. In 2011, she made her screen debut, acting as an au pair in French-Senegalese filmmaker Mati Diop’s short film Snow Canon. Since then, her voice and sound work have found their way into dozens of collaborations with musicians, filmmakers, writers, and artists.

Mobarak’s multifaceted practice radiates out from her performance work, which includes the ongoing series “Allophones Movement.” In it, collaged samples from the UCLA Phonetics Lab Archive are accompanied by live vocal improvisations. She designs her own costumes, odd-fangled assemblages intended to engage with ideas of transparency and shape. Periodically, Mobarak, who will have been moving continuously around the space — sprinting, standing, sitting, singing — collapses. The aim, she says, is to investigate the affective power and limits of the human voice outside the fixed meanings of language.

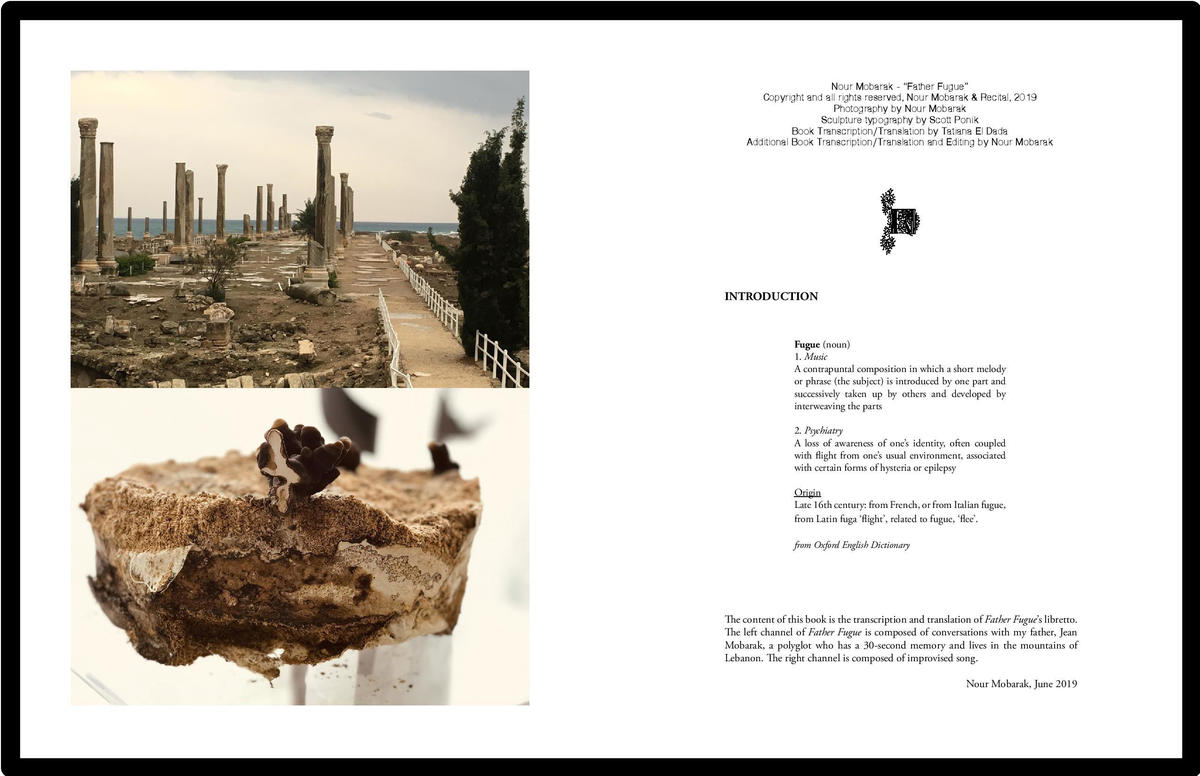

Mobarak’s debut full-length album, Father Fugue (2019), exists as a vinyl LP, a digital stream, and a series of column-shaped sound sculptures she has grown from mushrooms. It reflects nearly two decades of artistic engagement with her father’s existence in and despite language: Jean Mobarak speaks fluent Arabic, French, English, and Italian, but he cannot sustain conversations due to a neurological anomaly that limits his ability to retain a line of thought for longer than thirty seconds.

Father Fugue is remarkably ludic considering its emotionally fraught subject matter. On the album, Mobarak and her father play word games, sing, and engage in heartbreakingly recursive conversation. A patchwork of interconnected vocal pieces and lo-fi recordings from Mexico and elsewhere, the album’s riffs on the fugue — signifying both the contrapuntal composition in which a musical phrase develops through repetition and the loss of awareness of one’s identity — are a sonic delight.

Bidoun invited the artist and writer Jace Clayton, also known as DJ/rupture, to talk to Nour about the backdrop to Father Fugue, the surprisingly bearable lightness of being, and the specter of serendipity.

JACE CLAYTON: Can you tell me a bit about your father? The album Father Fugue is explicitly built around him. When did you decide to explore your relationship in this way?

NOUR MOBARAK: My father has lived in a nursing home in Bhersaf, a little village in the mountains of Lebanon, since 2007. His brain has been deteriorating for a very, very long time; it’s been a slow process. It started to become undeniably serious a couple years before I started studying literature and media at the University of Sussex in the UK. I had become obsessed with his cognition and language, in part because I was reading a lot of linguistic and critical theory at the time. He speaks four languages, but his memory is decaying. He can still switch fluidly among languages, but he remembers very little other than some essential things. He loves Juventus. He loves Italy. He loves Lebanon. He loves his first dog as a child, Happy. He loves his late uncle Camille (“un très grand homme”), me, spaghetti alla carbonara, Alfa Romeos… Other than that, he doesn’t remember much, though he speaks eloquently and kisses the hand of any woman who walks into the room. He maintains immaculate manners and has a kind and gentle disposition. He’s a delight. Interacting with him is so rich.

JC: What does that interaction look like?

NM: I’ve been recording and filming him for years. It always felt like an obvious thing to do. I love him, and recording became a playtime activity, something we could do together, since what one considers “normal” communication was breaking down, becoming impossible. I would film him on my DV camera, play it back for him. He would laugh then immediately forget what had transpired. It was fun. Heavy, but fun.

JC: I find it exciting when an artist deals with a topic or theme that suggests a multiplicity of formal outcomes. We have to be ready to end up in unexpected places. Why did this long-term engagement with your father eventually coalesce into an album?

NM: The project has taken various forms over time. I originally had a lot of ideas about how I might work with the old concept of the “memory palace,” a strategy orators have historically embraced to remember long speeches. They would memorize the interior architectures of buildings and place imaginary tableaux of objects in each room, the objects each symbolizing some word or concept in the text they were to recite. As they spoke, they’d walk through the cathedrals in their mind, look into each room, and see the tableau of symbols, and this would activate their memory of the text. I thought I might make a film made up of symbols that would generate some kind of text about my father’s life. I was imagining a film that would be sort of like Parajonov’s The Color of Pomegranates meets Beckett’s Molloy. But it became too overwhelming. I needed a producer. Actually, just before I abandoned the film, I wrote a letter to the one person I was sure could help me get it done: Werner Herzog. [Laughter] It was a long and detailed letter, which began, “Dear Werner Herzog, I am a very beautiful woman.” [Laughter] I never sent it, of course.

JC: Herzog is a German superhero to many people, not just you. [Laughter] But now you’ve got me thinking about how the idealized spaces of a memory palace are private, not shareable as such. Whereas much of the work of a music producer lies in architecting a sonic space for the listener to inhabit.

NM: Maybe because I was thinking about the architecture of the mind and language, I ended up with a very spatial record. It relies heavily on the sounds of the spaces in which it was produced, like the jabbering background noise of Lebanese TV at the nursing home.

Just as I was thinking about all of this, I got an invitation to put out a record from Sean McCann, of the Los Angeles–based label Recital. At that point, I had gathered a lot of recordings of conversations with my father, and I also had a lot of voice memos capturing my own improvisational singing. I wanted to fuse them because listening to them together made me think a lot about melody, sound, feeling, psychic spaces, and language. So that’s what I did.

I guess I was interested in the economy of using voice only, and the voice as it related to space. There’s the ephemerality. There’s the invisibility. There’s so much detritus that emerges when you’re making a sound piece. The exchange of more or less meaningless vocal utterances between my father and me makes for all this invisible floating material. The form felt correct for the work’s interrogation of memory, presence, and illness; you’re trying to trap a memory, but you can’t, even though you’re sure it once existed.

JC: As our parents age or become infirm, we eventually have to care for them like children and talk to them like children. Father Fugue captures that difficult reality, while emphasizing a sense of play instead of loss.

NM: So much of the pleasure of spending time with my father is simply listening to the potentialities of the human voice. He’s a great case study because he speaks four languages very well and can really round out all of the sounds. I love his voice, it’s pitch-perfect, and I suspect that if he had wanted to, he could have pursued opera. Or been an artist. As a student, he was kicked out of Cambridge for painting the gargoyles hanging over the medieval walls red. He really should have been some Fluxus artist, but because of his bourgeois Lebanese background he studied political science instead. [Laughter] Anyway, because he forgets whatever we’re talking about pretty much every thirty seconds, there’s not much to talk about besides the fact that we’re talking or just playing with language. I love the hybrid linguistic morphemes that end up being created between us. It’s interesting to hear language divorced from meaning. It can be liberating.

JC: Language is a form of world-building. Even if one can’t follow a conversational thread for more than a minute, this polyglot fluency — and pleasure, not fear, at its breakdown — confers a kind of belonging.

NM: There was something interesting to me about the fact that what we were saying was less important than the fact that we were actually paying attention to each other. The content becomes somewhat irrelevant. It’s more about the materiality of presence and voice. In a way, his relationship to memory and language — the way that giving or showing each other quantifiable amounts of attention sometimes became the true content of our conversation, rather than what was actually being said — became for me a synecdoche of modernity.

At the same time, there are flashes of something sensorial or melodic, something that suddenly falls into a kind of rhythm or groove, where a sensual pleasure is arrived at by surprise. The vocal scholar Nina Sun Eidsheim talks about the voice being constructed equally by the listener and the speaker.

JC: Here’s a funny story. When I first listened to Father Fugue, only my right speaker was plugged in. I had to crank the volume because it was so quiet. The right-channel listening experience feels very interior — there’s a female voice, and she’s on her own in this oneiric state. All the relationality that you get in the left channel, which contains you and your father communicating, is absent. In stereo, it becomes a totally different record!

NM: Right. The A-side is kind of three records. There’s the option of listening to the conversations alone, then there’s the option of mostly listening to the sort of song stems, or whatever you call them — the song parts. And then there’s the other one, which is the amalgamation of the two. I suppose I wanted people to be able to think about what we choose to hear when we “listen.”

JC: It’s interesting that you brought up Beckett, because he occurred to me as well. One of the things I love about pop music, philosophically, is that it’s anti-essentialist. It celebrates surfaces and fluidity and metaphor and money. Pop is antithetical to the integral modernist self. Contemporary pop music’s vocal manipulations and teams of songwriters and producers and makeup artists work together to create personae in a very conscious way. I love that.

This is obviously a personal record, and I was drawn to its performance of authenticity, the wind noises and low-end rumbles. It’s easy to prevent or remove those microphone-handling noises that signify acoustic sincerity. Which you didn’t do. That’s what got me thinking, Yeah, this is like Beckett, meaning that the listener is presented with a modernist voice whose integrity exists precisely because it’s being attacked in all of these ways that revolve around language and memory.

NM: That’s so cool that you thought of Beckett. I wrote my undergraduate thesis on Beckett. He’s so pervasive. I think that if you’ve been engaged with his ability to dismantle language, to make that very dismantling intrinsic to the subject, and to go inside of it in order to externalize it — if you’ve been immersed in how fused the content and the form is in Beckett — it really sticks with you. And that, I think, is something that I just haven’t let go of. Also, my dad reminds me a lot of Molloy.

JC: How so?

NM: There are weird correspondences. Like, in the novel, Molloy has a stiff left leg, and when I turned up at the nursing home with my camera and a copy of Molloy to start developing my film idea, my dad had a stiff left leg. He’d get up in the middle of my talking and walk in a circle with his stiff left leg and sit down. In the novel, Molloy is given pages to write, he doesn’t know what for. My father would be given pages to translate — he didn’t know why. My father had been given the task of translating old dictionaries by his caretakers at that point, to keep him occupied. He did it very well.

JC: Sure.

NM: They also have a similar sense of humor! When I was writing that thesis, I also read a lot of Pierre Bourdieu, the French sociologist, and I was thinking about the intersection of humor, education, and class. Because I would go to performances of Beckett plays, and the audiences would barely laugh.

JC: I picture you giggling nonstop and getting glared at by too-serious theatergoers.

NM: Basically. It was like their dread of the void made it impossible for them to find the humor in Beckett’s bathos. It was too sad or disturbing or something. [Laughter] So I organized study groups where I would show BBC videos of Beckett plays to children and record them reacting. And then I wrote about that. It turned out that the children found it very funny. They responded to the slapstick and the clowning and the tragedy.

JC: That’s great.

NM: And you know, when I would read Molloy to my father, he’d laugh and laugh.

JC: Like, he got it.

NM. He got it. He’d forget it, but he got it. But anyway, about the wind sounds and other sonic marginalia that I could have filtered out: Those were also my attempts at sound production. Because it’s like, Oh, well, at least there’s a little texture there. There’s something for the people. They get a nice wind sound.

JC: Nour, you’re so generous. [Laughter] Those sounds also remind us that many of these songs are meant to read as improvised, off the cuff. What does improvisation do for you that other, slower forms of music-making might not?

NM: It’s a matter of my temperament. For a very long time, I was making a lot of art and not releasing any of it because I was so precious about it. I would say, “This isn’t perfect. This isn’t right. I can’t get this straight.” But I do enjoy an embodied and spontaneous approach to making art, in some ways in spite of myself, and I was compiling so many of these voice pieces in particular — these improvised works. I don’t necessarily think of them as more authentic than anything else. In other words, I don’t romanticize improvisation. Again, it’s a matter of economy. I can sing anywhere. In the context of these conversations with my father, though, improvisation is what made the most sense.

JC: I’d like to talk about the section where we hear improvisation’s opposite: you teaching your father a melody by repetition. What’s going on there?

NM: We had a house that was in our family for thirty-two generations in a small village called Fleurance in the Jura region of France. When we were selling that house and getting rid of all this accumulated stuff, I found stacks of published music. It turned out that they belonged to my great-great-grandmother, a French woman who had studied at a music conservatory. Her name was Lucie Lary, but she changed it to Lucie d’Halencourt, faking the nobiliary particle to sound… noble. At some point, she had won a first prize that entitled her to be shipped off to Constantinople. She became, according to my great-uncle, the Ottoman court pianist. This was around the turn of the twentieth century. She was the piano teacher of the emperor’s children and started the French conservatory in Constantinople. To be honest, I don’t know if that last detail is true, but what is certain is that her daughter Laure married a lawyer from Jerusalem, Négib Bey, and that’s part of the reason we’re all Francophone Arabs. So at the end of the record, there’s this piece that involves me teaching my father one of her songs. Music from a hundred years ago is repeated by her descendants, one of whom has no capacity to remember it.

JC: That’s fascinating. There’s this vision of your great-great-grandmother as a musical colonizer who’s bringing the piano, those eighty-eight keys with their fixed Western tunings, to Turkey. Forget about your quarter tones! More broadly, it seems to me that the place where you and your father meet with most parity is as listeners, through these vocal games. It contrasts with narration and memory, where there’s a massive imbalance: You’re capable of these things, and he hasn’t been for decades now. The relationship between his mastery of Arabic and Italian and your not speaking either is also at play. What does it mean to meet in these moments of language games? I think of it as like musicians who don’t share a language: Music is the space where they can converse.

NM: There’s always a moment when sheer musicality comes to the fore. For example, I love the sound of Italian. I love the cadence. Even though it’s a language I don’t speak, it’s very musical to me.

JC: I understand your mother also has a significant musical legacy?

NM: Yes! According to family lore, and I say “lore” because she doesn’t talk about it, she was the star of a Lebanese television show called Toute la Ville Chante in the 70s. This is all based on oral history, but basically as a fourteen- or fifteen-year-old she ran away to Avignon from her home in Geneva because she wanted to join the theater world there. She was forced to come back to Geneva, but then she escaped again — this time to Beirut — when she was sixteen. She was half-Lebanese, half-British. In Beirut, she became a radio DJ, had a kids’ show, then was eventually invited to be the host of Toute la Ville Chante when she was twenty-one. It was a French-language program featuring French celebrities who visited Lebanon. My mother was telegenic, a blonde Arab, and fully Francophone, with an outrageous personality, so she was a perfect host. She would sing and dance and interview celebrities like George Brassens or Veronique Sanson. She even interviewed Alfred Hitchcock! Who knows why. [Laughter] I didn’t make the connection until much later on. Someone said, “You followed in your mother’s footsteps.” There I was dismissing her bourgeois bearing, when in fact she has this rarely spoken about past. It was a surprise, to say the least.

JC: I find the photo on the back of the record compelling. It captures you and your dad in what must be his room at the nursing home. It’s a weird image — not the two of you, but the stuff in the background. There’s a blank whiteboard on the wall, and then a couple of framed photographs, and then a big black LCD TV, which is partly eclipsing one of the frames. There’s a loose photo on top of a mini-fridge. [Laughter] It’s a collage of image-making mediation that manages to feel ad hoc and composed at the same time.

NM: I was definitely trying to capture that bizarre room and how freighted it is for me. My dad’s been in that same room for fourteen years, with the cheap tile and the plastic chairs and the broken hospital bed and the plastic picnic table. There’s also a broken door that leads to a little balcony with a view that looks down from snowcapped mountains to palm trees to the sea.

JC: It’s such an uncanny space. It’s definitely not familial. It’s clinical but lived-in. Neither comfortable nor uncomfortable.

NM: I feel like I sometimes fall into a fugue state when I’m there. The architecture of that space is very transporting. Not just his bedroom. There’s the hallway we used to pace back and forth together for hours and hours, the pasted-on church in the basement. I’ve spent probably hundreds of hours watching Arabic TV in the living room, the nurses smoking or falling asleep while the other residents are screaming or having episodes, and my dad just sits there, politely smiling. The experience is so charged and at the same time so naturalized. I mentioned my film idea earlier — the possibility of building a film using a memory palace. Well, that idea was always linked to the architecture of the nursing home. The idea was that you would walk down its halls and look into room after room to see symbolic tableaux within this very specific environment — homely, quasi-institutional, dilapidated, with some part of the mountain heritage still present, resonating something archaic and beautiful.

JC: I’m curious about your relationship with field recording, or rather, the act of documenting, because it seems to me that Father Fugue is not so much about capturing the aural essence of a space, even a space as uncanny as the one where your father lives, but is tapped into other energies as well, like how language contours one’s sense of the world.

NM: I suppose my record is interested in field recording insofar as it’s rooted in particular locations. To me, it was more like a very minimally produced document of melodic ideas that were captured and then left as they are.

JC: I think of recorded music as a continuum, with hyperproduced pop songs at one end and single-microphone recordings at the other. Every point on that spectrum involves many layers of mediation, selection, and editing, even if the sound is raw or folksy. There’s really no neutral recording environment. A few of Father Fugue’s titles conjure up very specific famous pre-Colombian spaces in Mexico and put us in “field recording” mode — “Monte Alban Scream,” “Oaxacan Shower.”

NM: I was going to mention “Oaxacan Shower.” Again, the incidental sounds are essential to that track. I wanted to create a document of somebody going into the psychic space of singing in the shower and singing with water. It’s site-specific. I was actually taking a shower in Oaxaca and singing.

JC: I have this record, Home Tapes, by a sound artist named Alejandra Salinas. She co-ran a label called Lucky Kitchen that was interested in the social residue and context of different types of sound-making. For Home Tapes, Alejandra took cassettes she’d recorded as a nine-year-old and, twelve years later, edited them together into a 10 inch record. It includes a full transcription of everything she said. She’s talking about having a stomach ache, she’s talking about wallpaper, she’s having a silly conversation with her father. These words are translated into English, German, Japanese, Swedish, and Basque. Her work resonates with yours: You’ve both produced records of the mundane. Textures of the everyday, without any grand narrative, and also without the concision of a pop song. Both Father Fugue and Homes Tapes find it important to physicalize the traces of private sound interactions. Even more striking, both records make a point to transcribe and translate what is being said. It requires extra care — and extra people — to propagate this personal speech from one language to another.

NM: Yeah, that’s where the production lies. The booklet that comes with my record includes a transcript of my conversations with my father, and that was really important. We printed more copies of the booklet than we did of the record. It’s its own object.

JC: As an object, it feels like a document of cognitive dysfunction in language as well as a poetic text. What is your relationship to the poetic?

NM: I read and write a lot of poetry, and I’ve made concrete poetry too. The booklet’s text is divided into columns. It’s impossible to read the columns simultaneously, and yet you can listen to the different tracks simultaneously. You can say Father Fugue presents a spectacular language problem. I suppose our whole lives are language problems.

JC: Yes! A life sentence.