Amr Khaled has great big expressive eyebrows. When he speaks, they take on a life of their own, moving up and down and sideways like a caterpillar on acid. Whether pondering the state of women in the Islamic world or the fate of the Palestinians, he is relentlessly, even frustratingly, optimistic. As the Egyptian equivalent of Dr. Phil, Oprah, and Rick Warren all rolled together, he is an army of one dreaming of the Islamic Renaissance to come, a pious poster boy, hero, and self-help coach to millions.

I first met Khaled at a blandly posh hotel in London’s Knightsbridge district last winter. The gentle giant — he is well over six feet tall and shaped like an athlete — jumped up to greet me and heartily shook my hand with the energy of a large affectionate dog. That day, he was even more animated than usual, pleased that a new reality show of his, Mujaddidun, was set to air on Dubai TV. Though I was there to interview him about something and someone else entirely — his longtime collaborator Ahmed Abou Heiba — he kept bringing the subject straight back to… himself. Had I heard of his new show? Did I know that his website, amrkhaled.net, receives more hits than Oprah Winfrey’s? Had I heard that he had convinced three million girls in the Arab world to give up drug addiction? I nodded, smiling, always trying to bring the subject back to his friend. Always failing.

“There are no jobs! No place to play ball! No hope! Too much depression!” Khaled was yelling about the state of the Arab world and why he had launched this newest initiative, inspiring the well-heeled clientele in the lobby to glare at the overexcited Egyptian. “We must take control of our lives and realize that Islam is the path forward, not the path backward, as people would have us believe.”

It’s almost physically impossible not to listen intently to his monologues. Khaled is frighteningly smooth. On television, he expounds from behind a desk as the camera zooms in and out and in again. He pumps his fist or stands, arms akimbo. He makes love to his audiences with his big brown eyes. Whatever one’s afflictions, whether joblessness, lost love, or simply feeling worn down by the clash of civilizations, Khaled makes it all seem okay with his trademark seizures of optimism. He is the king of eye contact, enveloping viewers with his heavenly regard as if to say, “It’s okay, you’re having a bad hair day, but Allah still loves you.” More than once in the hour we sat together, I was reduced to putty in his hands.

Khaled, as it happens, is not your prototypical religious speaker. With no theological credentials to speak of — he originally studied accounting — he puts forward a moderate version of Islam in which women are heroines, the prophet is your friend, and the treacherous stuff of modern life, from listening to music to using technology, is just part and parcel of being alive. Under Khaled’s gaze, one can be pious and modern at once. In fact, it is Islam, he says, that provides the best equipment for modern life’s travails. Islam is the tool kit par excellence, and Khaled is there to show us how to hold the hammer. (To screw in the light bulb?) At a time when the world wonders whether the values of Islam and the West are compatible in the first place, Khaled is a living, breathing advertisement for fusion.

Khaled’s fortunes have been on the rise since the late 1990s, when he connected with an old friend, Abou Heiba. Khaled had been delivering lay sermons — on the importance of hard work or patience or other good things — at a neighborhood mosque for years. Abou Heiba, on the other hand, was thinking of launching an Islamic television program that would mark a radical departure from the standard moralizing one routinely saw on TV courtesy of the iconic Egyptian Sheikh Mohamed Sharkawi. Sharkawi terrified his audience with apocalyptic warnings about hellfire and the afterlife. Soon, Kalam min el Qalb (Words from the Heart), was born — a program produced by Abou Heiba, with Khaled as its charismatic host. They hawked their initial episodes on the street when no major television channel would pick them up. Those street copies sold out immediately, and soon Iqraa, a Saudi-owned religious channel, bought the rights to the program.

Words from the Heart, which opened with a heroically low-tech montage of Khaled preaching, young people praying, and a woman in the act of veiling, would come to change the face of Islamic television. Suddenly, someone was offering up an alternative to long-bearded preachers who spoke of sin and redemption; here was someone talking about real life! On each episode Khaled, who has a tiny brush mustache, looked out from behind a desk and broached issues at once banal and thorny. Even when speaking about more grim subjects, like death or Palestine or the wages of war, he rarely lost his exuberant joie de vivre, or his mile-wide smile. He wore colorful suits and boxy Mister Rogers sweaters. Perhaps most important, he delivered his sermons in colloquial Egyptian Arabic rather than the turgid classical Arabic of his peers.

And yet, despite the myriad accolades (he was named one of Time’s most influential people in the world in 2007, and joined Newsweek’s Global Elite in 2008), it is not easy being Amr Khaled. His particular brand of lay sermonizing seems woefully deficient — or even blasphemous — to more conservative theologians. When it comes to the Qur’an, he is, you could say, a first-class paraphraser. The fact that he commands such a following eventually raised the ire of the Egyptian authorities, who ran him out of the country around 2002 and have banned him from appearing on either public or private television. He has been accused of being associated with the semi-banned Muslim Brotherhood, as well; his very public advocacy on behalf of the veil (“women are like pearls, they need a shell to protect their delicate beauty”) renders him predictably suspect to Islamophobes the world over.

Women — who no doubt account for his biggest fan base — are often the subject of his rhapsodizing. “We must concentrate on women and youth to make our future,” he says. “You must remember, the first one to help and support our prophet was a woman!” (He is speaking of the prophet’s wife, Khadija.)

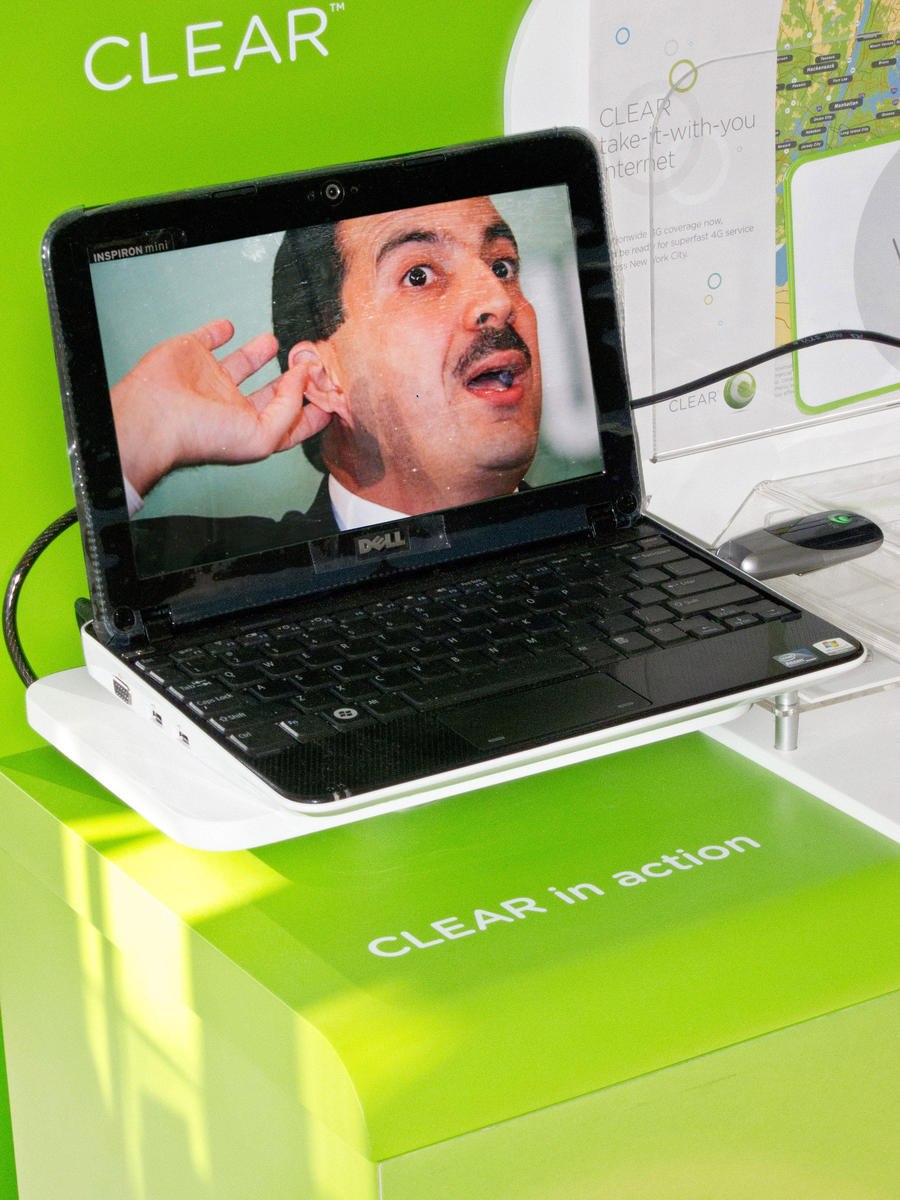

On the issue of the media, he is rapturous, deeming it a critical platform from which Muslims may regain their lost dignity and speak to the world. “We need movies to talk about the overlap of values between America and the Muslim world. This will help a lot.”

Since 2002, Khaled has been living in Europe and, as a consequence, has increasingly turned his gaze to the fate of Muslims there. In 2004, he launched a new program, Life Makers, which urged Muslims to seize control of their lives through projects in their respective communities. In 2006, he courted controversy in the Islamic community for taking part in the so-called “Copenhagen Conference,” in which he called for reconciliation between the West and the Islamic world after the Danish cartoon scandal. By 2009, he was en route to launching Mujadiddun, a reality show in which young people in Arab cities go about solving problems and doing good deeds. (“Mujaddidun” is the plural of “Mujadid,” which refers to someone who appears at the end of a century to revive or reform Islam.) This year, somewhat incongruously, he completed a PhD in Islamic Studies from the University of Wales. (His Wikipedia entry, which one can’t help but think he updates himself, announces that he finished with a grade of A.) Now he goes by the honorific Dr. Khaled — or in Arabic, “El doktoor.”

When I spoke to him this past fall, he told me that he couldn’t possibly tell me about his latest initiative. But he could not stop not talking about it. “I wish I could tell you, ya Negar! It is so exciting!” I half-expected he would spill the beans, but despite everything, he did not. In any case, I believe him. Upward and onward, to the Islamic Renaissance.