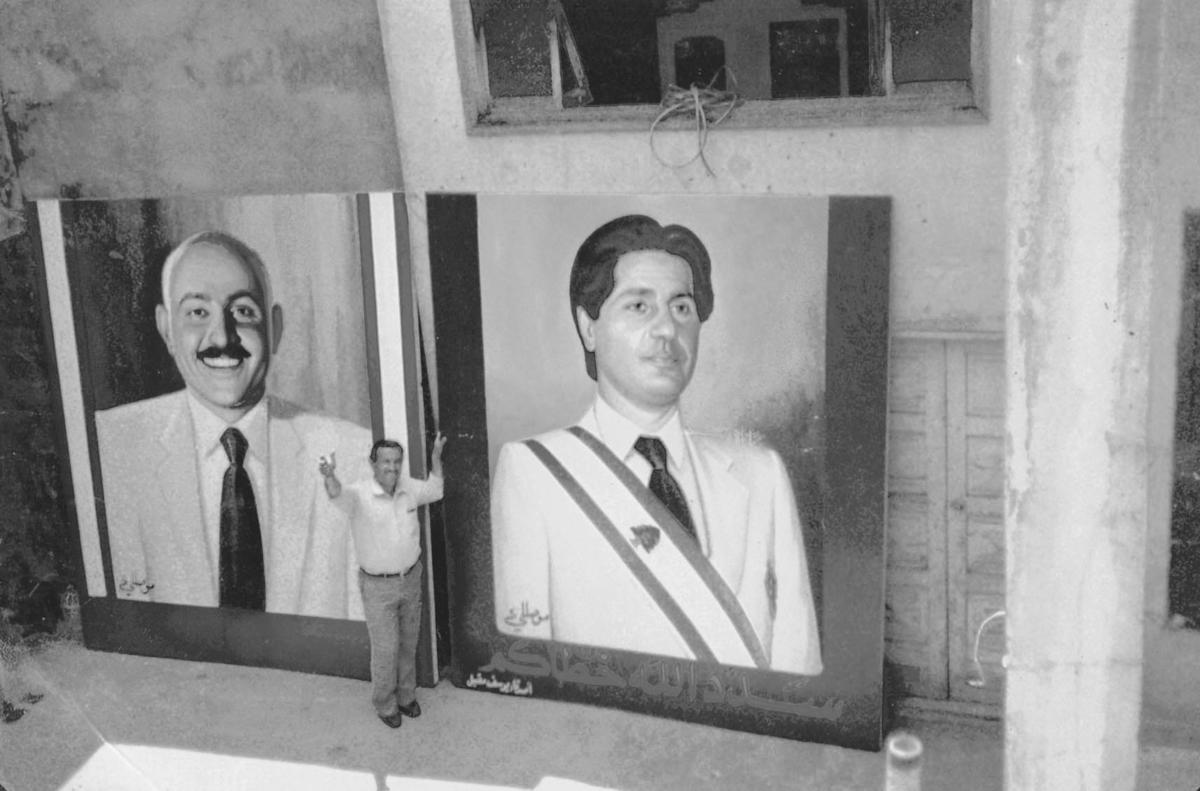

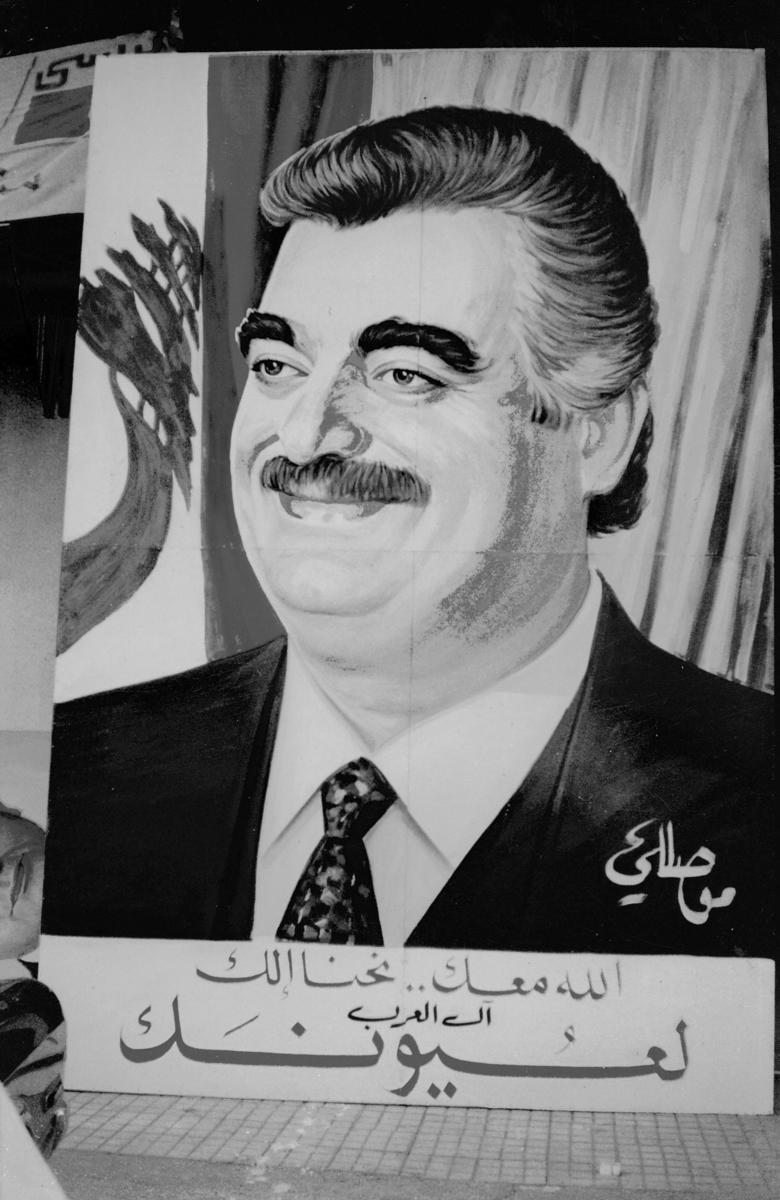

From the late 1960s to the ’90s, Mohamed Moussalli’s signature graced portraits of nearly every Lebanese political figure. From the Shia spiritual leader Moussa Al Sadr, with his wise-man’s gaze and perfect imama, to former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, with his big-boss stature and bushy eyebrows, Moussalli’s portraits radiated a distinctive magic that was equal parts father figure, film star, and cowboy. Before becoming known for his political faces, he was painting icons of modernity for advertising companies — from gleaming refrigerators to sports cars to American cigarettes. Today, at sixty-eight, the man once known as the King of Portraits is retired, though he still spends his days in his overcrowded studio in Dahieh, Beirut’s southern suburb, amid jars of paints and brushes and beat-up projectors. On rare occasions, he regales visitors with tales from the past, especially lingering on the subject of how his art forever changed with the advent of computers. Here, he speaks to Zeina Maasri, graphic designer and author of Off the Wall: Political Posters of the Lebanese Civil War.

Zeina Maasri: How did you get your start painting?

Mohamed Moussali: I started drawing when I was between five and six. No one taught me. I developed on my own and finally made painting my profession.

ZM: And what kind of painting was that?

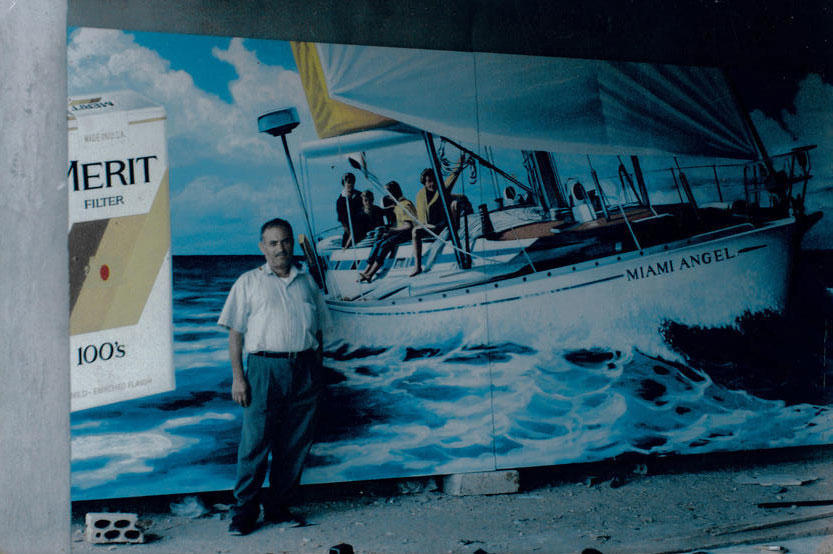

MM: Every kind — oil painting, portraits of notable figures, decorative murals, ceramics, and advertisements for big brands. I did plenty of the mega-scale billboards, the ones that used to line the main highway leading to the airport. I don’t know if you recall those big Marlboro ads?

ZM: Were you ever interested in an academic training in the arts?

MM: I wanted to go to art school in Spain, and many established artists in Lebanon encouraged me to do so. The school required a portfolio of drawings and paintings. I prepared all the requirements except for the female portrait. I didn’t know whom to paint, and no woman would allow me to. So I chose for a model my cousin, who later became my wife… [Smiles] She was still a little girl, very beautiful back then, maybe fifteen years old. It was very innocent. At first she refused, but then accepted on the condition that her sister sit with us as chaperone. She wore a purple and white dress, her hair was long with a golden color, and she let it down on one side.

ZM: What happened? You didn’t make it to Spain, did you?

MM: My father burned the portrait. He set fire to all the paintings I had prepared. He was a very religious man who believed that God forbids painting and representation of human figures. I continued painting while he kept on repeating that I would eventually lose my sight because I used to spend whole evenings working. He was right about the sight, I guess.

ZM: How did you start working with ad agencies?

MM: They were all lined up on Khan Antun Beyk in the old souks of Beirut. I can’t remember all their names: Decora, Bahlawan, INA, Adverco… the best ad agencies in town. I was around thirteen when I knocked on their doors. They used to hire this one artist, an Iraqi or Jordanian, I can’t remember, to draw their ads. When I showed them my work, they hired me instead and never commissioned him again. They would show me a picture or express an idea, and I would just draw it. I drew all sorts of things in different scales: airplanes, wheels, and cars… all the modern products that came to Beirut in the ’60s. I got into trouble, of course. I once painted a mural right next to a chic beach resort on the southern outskirts of Beirut. I drew a girl half-naked in her bikini. The ad was for modern refrigerators — Frigidaire — so the girl was supposed to be feeling hot in the summer. That was the idea. [Laughs] The next day, the police arrested me. The wall I drew on turned out to be an abandoned church, which filed charges against me. The owner of the ad agency came to my rescue and apologized to the parish priest.

ZM: And political figures?

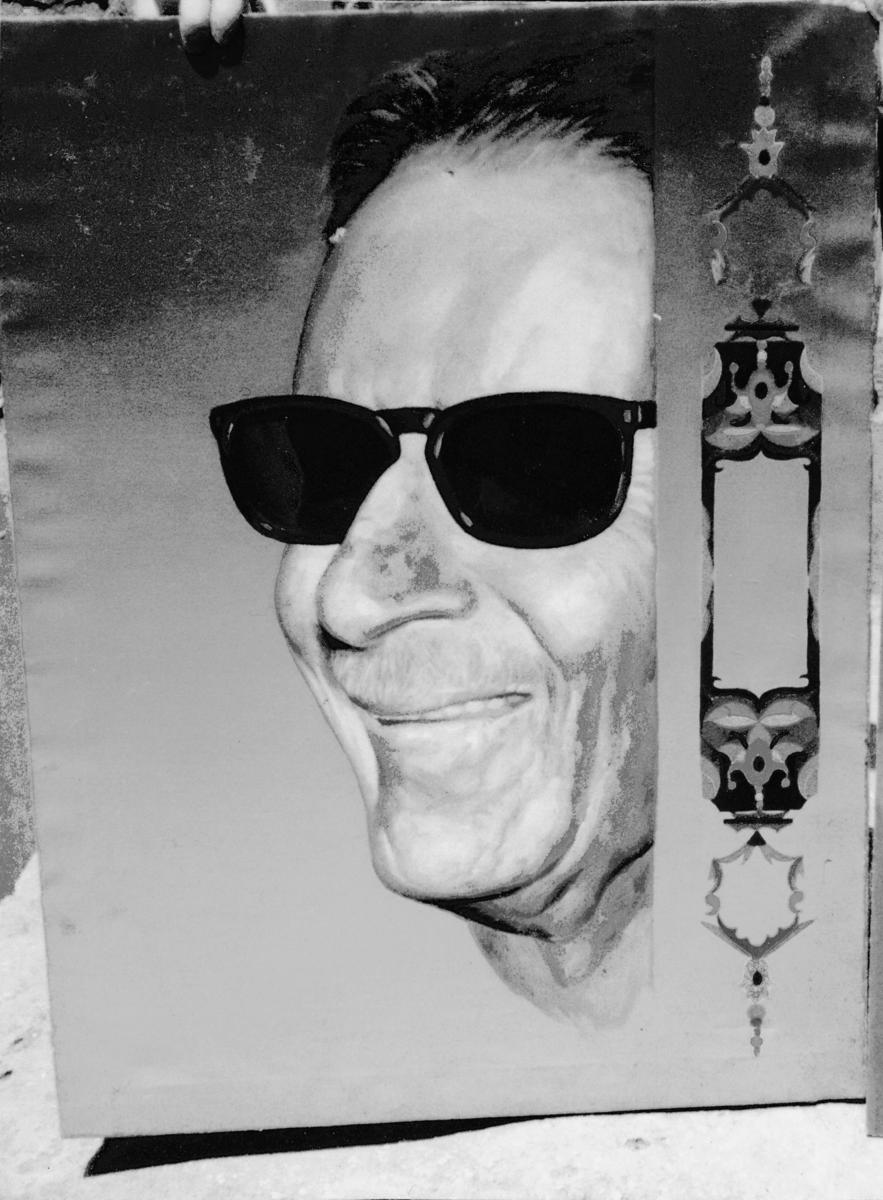

MM: Sure, I had waiting lists of two to three months of political figures during parliamentary elections. There is this great mural of Nasser that I did, too, with his sunglasses on and fighter jets soaring around him.

ZM: When was that?

MM: That was already in the late ’60s. And then I painted a great number of candidates’ portraits for the elections that took place just before the 1975 civil war.

ZM: You mean the 1972 elections?

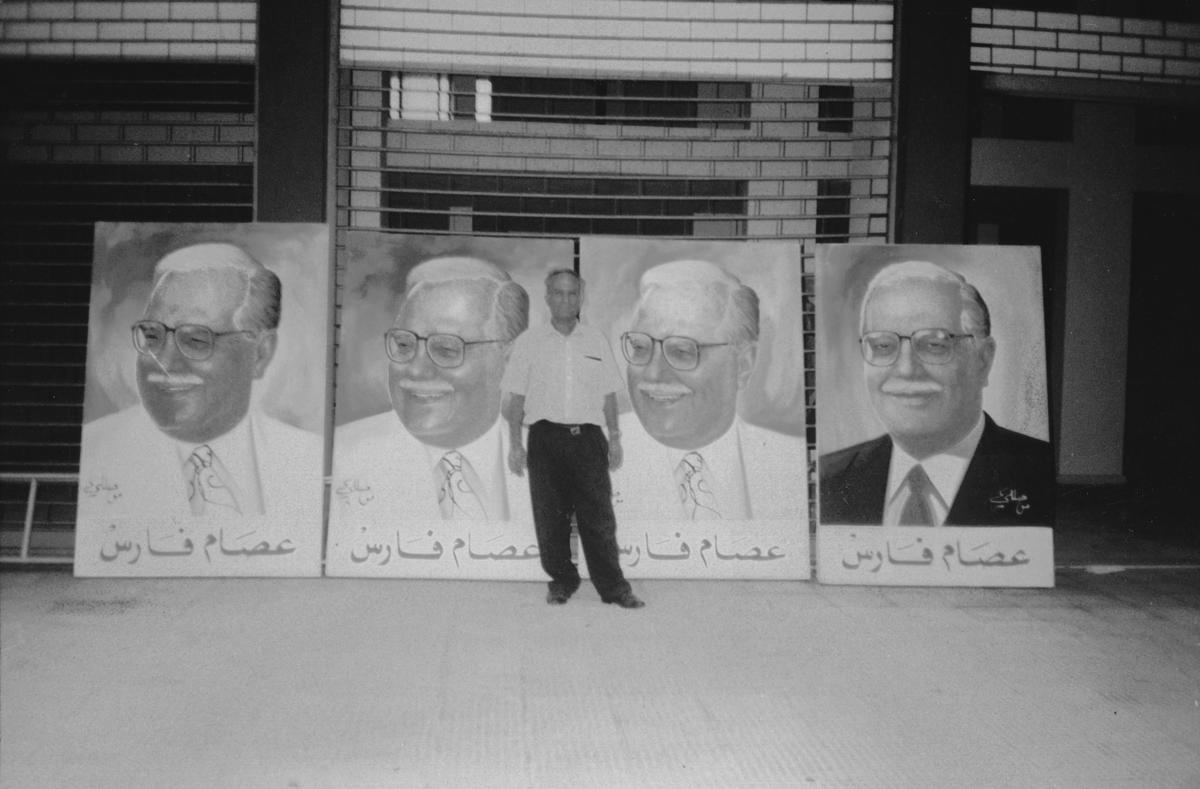

MM: I think so — the dates elude me. I still remember the total number, though: it was 3750 paintings. I would do seventy to a hundred identical portraits for each candidate. If you compare the first to the last one, you’ll see that they are exactly the same. I painted fifteen to thirty portraits per day. I used to line them up on the street outside my studio so that they would dry fast in the sun.

ZM: That’s an incredible number. It’s what a printing press would do. Why wouldn’t they simply print posters instead?

MM: At the time, the largest size of a printed poster would be a maximum of 60 centimeters, and it would be of low quality, mostly in one color. Whereas I could do a much bigger-scale colored portrait that they would put up on the street. This brings more authority and grandeur to the subject. You know, politicians like that. I did this portrait once that was 14 meters in height and 6 meters wide… [Laughs] It broke during the rally, so they brought it back to be repaired.

ZM: Did you have any competitors?

MM: No, I was the best. Sometimes, I had no time to eat! My wife would feed me sandwiches while I would stand and work. She also helped me trace the lines to make the copies.

ZM: Did you ever design a poster that got printed?

MM: I think I once designed a poster. It was for the Palestinian resistance. I drew a tree trunk formed by a group of fida’iyeen, symbolizing land and resistance. These were popular issues back then. I also painted a portrait of the Egyptian writer Taha Hussein that was used for a book cover.

ZM: Do you remember whose portraits you did? Were there any political groups you worked with in particular?

MM: I don’t recall all their names now, but they were esteemed figures. I worked with various parties and political factions. I might have served more those who were within my area, that’s normal. When you live in an area controlled by one political group and they treat you well, you need to reciprocate. I didn’t hold a specific political adherence to any of the parties, so I didn’t scrutinize the commissions I got. It’s my profession after all, and I don’t get myself entangled in the politics of this country. I did portraits of Salim Al Hoss, the former prime minister, Moussa Al Sadr, I did three or four different portraits of Al Sadr. Amin Gemayel — I painted his portraits on large sheets of canvas in the ’80s, when he was the president of Lebanon… . And many more that I don’t remember. That’s all in the past for me now. Those days are long gone.

ZM: Any interesting story that marked you or incident you want to share?

MM: [Smiles] No, it’s all work… off the record? I’ll tell you later, you have to visit again. I never really had a major problem. It’s actually my brother who managed the business — he knew how to deal with the politicians. The key was to make sure that appointments would never overlap. The politicians would send their agents to pick up the work, and they’d all be armed with Kalashnikovs. I was worried that if opposing groups met, they would start a fight. The war days were very dangerous. I worked on a portrait once for a member of an influential non-Lebanese political group. the next thing I know, militiamen pulled me out of my home late in the evening. We were all very scared, my family and I. I had no idea what they wanted. It turns out that their boss was very pleased with the portrait and wanted to give me a treat by inviting me to dinner. Eventually, I was trapped. They forbade me to work for anyone but them. I was told that evening that I was to become the official painter of the party. I tried to get out of it, but to no avail. They told me, “These are your choices — either you work for us or we cut off your hands. You choose.”

A few months later, the Israelis invaded — it was 1982 — and the party’s headquarters was bombed, and they were forced out. I took my first opportunity to get out of the country, and stayed away for a while. They never paid me, by the way, not a single penny, for all the work that I did. I didn’t really care then, though, I just wanted to get away.

ZM: Was there any particular technique you used?

MM: I worked on the basis of a photographic portrait, which I would divide into a grid of small modules and then enlarge. Later I started using a projector that allowed me to enlarge on a much bigger scale. Of course, I didn’t need it when I was doing a series of the same person — once I had done it a few times, I would have memorized all the traits and could paint without referring to the picture. Why do you care? These methods are obsolete — my work is of no use to anyone now. With one click of the computer, you can get the largest portrait, in color. Look around you, Beirut is filled with politicians bigger than I could have ever imagined. They look real, but they have no life!

ZM: Well, most of them are dead, anyway. But what do you mean?

MM: It’s not the same. Portraiture is an art, you see — it’s not a matter of getting the portrait as close as possible to reality, but of rendering the figure more appealing than reality. The painter’s brush and his eyes bring emotion and life to a painting. The agents who used to pick up the finished work would be startled. Once, I realized that I had maybe gone too far, I made the man look handsome when in fact he was far from it. I was worried that it would not be accepted — the agent noted the difference, but seemed pleased with it. Okay, here’s another story: Once there was a portrait that I couldn’t finish. Something was odd with the eyes. If I fixed it, I thought, the man would not look like himself. The agents arrived, and I still wasn’t done. I told them, there is something wrong with his eyes; I can’t finish the portrait. They were of course upset and called the deputy to complain about the situation. And it turned out that in fact he had a problem with one eye that made it look different than the other one, but no one had noticed before — or at least, never dared to say anything.

ZM: Were any of your portraits failures, in your eyes?

MM: I was once commissioned to do a portrait of Abdallah El Yafi [former Prime Minister of Lebanon], so I based it on an available newspaper photograph. It turned out really bad. I realized when I saw a good picture of him that I had made a fool of myself. So I redid the portrait and delivered it to his house. His wife called the next day asking for twenty-five more portraits identical to the last one, which I did. A few days later, they asked for another set of twenty-five, and then another twenty-five — they just wouldn’t stop. I ended up knowing all his features by heart.

ZM: When did you stop working?

MM: My last job was in the ’90s, it was a portrait for General Aoun [head of “The Free Patriotic Movement”], or maybe Rafik Hariri. Since then, there’s been the invasion of computers. They wrecked everything. Anyway, as you can see, I’m losing my eyesight… I don’t paint anymore. [Laughs] These politicians have spoiled my eyes.