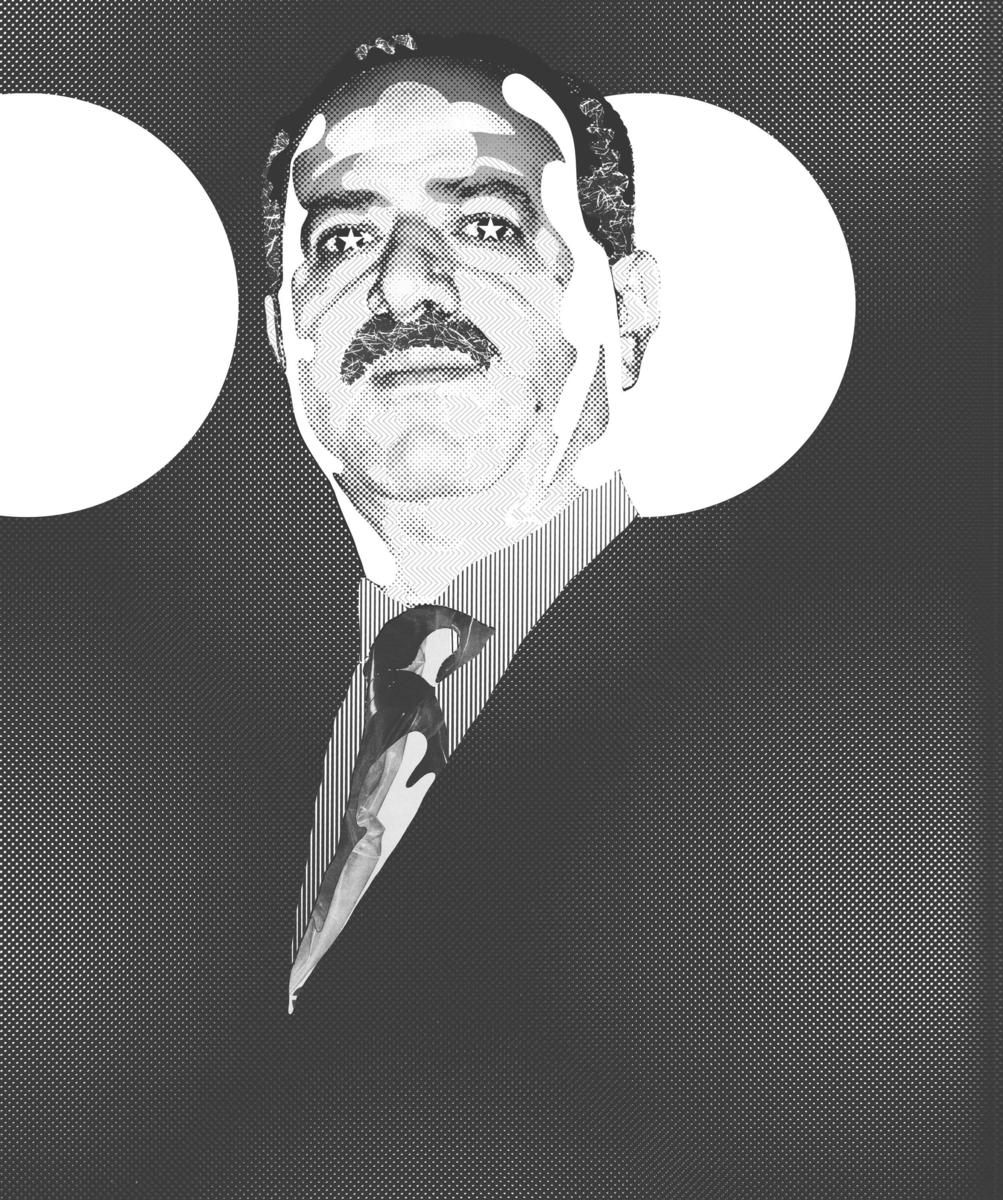

Mohammed Fares has been to a place almost none of us will ever go. One of only two Arabs to have ventured into space, the former Syrian fighter pilot tells Hugh Macleod about life in the stars and the lessons he brought home with him.

Hugh Macleod: On July 22, 1987, you blasted off in a Soyuz rocket from Baykonur in Kazakhstan with two Russian cosmonauts on a mission to the then Soviet space station, Mir. Of the whole amazing trip, what was the worst moment?

Mohammed Fares: The few minutes before takeoff. We had been in the rocket for three hours, and we were just sitting there waiting for someone to press the button to launch us. I can still hear those seconds ticking away in my head. The Russians played me songs by Fayrouz to help me relax! They need not have worried, though. When they tested our blood pressures and heart rates, my rate was 84 beats a minute, while the Russians were at 125. I was not anxious, because God decides my destiny.

HM: The only other Arab who has ever been into space is Sultan bin Salman bin Abdul Aziz Al Saud, former fighter pilot and grandson of King Saud. How does a prospective Syrian engineering graduate from Aleppo end up flying around the earth in a spaceship?

MF: I remember as a child watching from our garden close to the military college as air force fighter jets flew overhead. I always knew I would like to see the ground from far up. When I left school I had the grades to get into a civil engineering course. Instead, I enrolled in the military academy and started learning the ins and outs of the MiG jet fighter. I graduated fifteen days before the start of the 1973 October War with Israel, but I was too young to participate in it. In 1984, Syria and the Soviet Union signed the Intercosmos agreement, whereby the Soviets would provide training for non-Russians. The Soviets believed that fighter pilots would make the best cosmonauts because of our ability to withstand g-forces. In Syria we went from fifty pilots, to ten, then four. Then the Soviets came and chose myself and Munir Habib to go to Moscow. I think I was picked because I was in very good health and have strong nerves. Contrary to normal people, I become anxious if my son makes a silly mistake, but when there is a really big problem, I feel more relaxed.

The Russians played me songs by Fayrouz to help me relax! They need not have worried, though. When they tested our blood pressures and heart rates, my rate was 84 beats a minute, while the Russians were at 125. I was not anxious, because God decides my destiny

HM: It is safe to say that almost no one who reads this magazine will have ever been or will ever go into space. Can you tell us what it was like for the 7 days, 23 hours and 5 minutes you were up there?

MF: Well, the first thing is, it is just so tiring. You constantly have the feeling of falling, like at the top of a rollercoaster. You are actually falling around the earth at 26,000 km per hour. For most astronauts, five days is enough. But for me, every moment had its happiness. I felt my body free of gravity, and then I looked to the earth and asked myself: “What is this? Where are we? We are in a dark place. How far from the land we are. How are we to eat, how to sleep in this space,moving like the birds?” This was a new feeling for human beings who have spent thousands of years on the earth, weighed down by gravity. No one can really feel what the whole vision of the earth is, except the man in space. From space you don’t see tanks, planes, or armies fighting each other, only this dark calm in which the earth is as a mother. From space the earth is not your country, but your mother. But then there’s the problem of sleeping. It is very hard. You tie yourself down to the floor and to the wall, but still you move about. On the fifth night, I discovered the best way to sleep was curled up like a child in the womb!

HM: But you didn’t go into the starry firmament to gaze in wonder. Tell us the reasons for the Russians sending a Syrian into space.

MF: I was working on what was then the Syrian space program. Syrian scientists had prepared 100 experiments but the Russians said that would be too many for our eight-day trip, so we settled on thirteen. I had my own room to conduct research on the space station. We gave the experiments Arab names: Qassioun, Bosra, Palmyra. Some of the tests were to see how the human body reacted to time in space. Others were surveying air and water pollution and tracking African-Asian fault lines.

HM: What happened to the Syrian space program?

MF: Let’s just say we faced many scientific problems,and it was closed down soon after I returned. But the experiments I did for Syria are known and used throughout the world. One Russian cosmonaut even got his doctorate based on our experiments. Now I work in air force administration, and I travel the country encouraging young Syrians to take an interest in space and technology. I wish there were better scientific progress in Syria. The Israelis launch spy satellites, while we launch Arab satellites to broadcast television.