In 1965 Hürriyet, an influential Turkish newspaper, announced the Altin Mikrofon. Analogous to the contests that were already creating legions of “garage bands” in cities and towns across Europe and North America, Altin Mikrofon was, in some sense, a glorified battle of the bands. And yet the golden microphone played a unique role in shaping the popular culture of Turkey at a vulnerable moment in its history. From another angle, it might be thought of as one of the most successful cultural nationalist projects in the golden age of cultural nationalism.

As Hürriyet explained, “The Altın Mikrofon contest aims to open up a new space for Turkish pop music, using techniques, formats, and instruments of Western music.” Some room already existed — Turkish musicians, some of them educated abroad, had been playing R&B and rock since the late 1950s. The Shadows had been highly influential at the start of the decade, not least because their flamboyant instrumental music could be appreciated without knowing or caring much about the English language.

But the Golden Microphone laid down a particular gauntlet: Contestants had to play Western instruments, and they had to play “Turkish music.” At a minimum, that meant inventing new Turkish lyrics to go along with borrowed melodies from abroad. But it could also mean seeking out songs from the rural areas far from Istanbul, played on traditional Turkish drums and stringed instruments like the saz or bağlama, and rearranging them for the standard Western guitar, bass, drums, and keyboards (and sometimes saxophone). It was like a pop-era cover of Ataturk’s retro-futurism: insisting on complete modernity while turning to the past for inspiration and a sense of belonging.

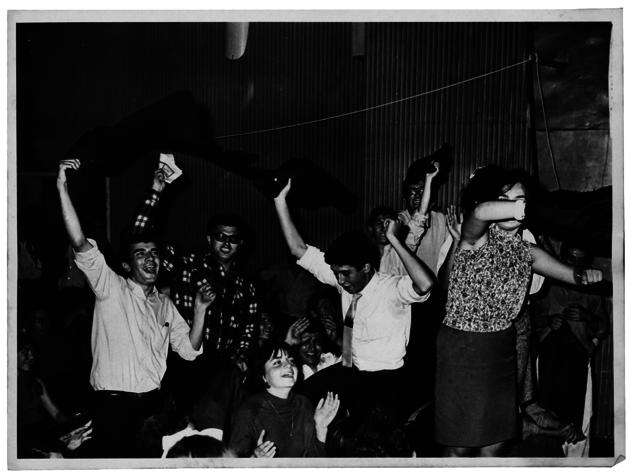

Contestants were evaluated first by a jury of music-related personalities. Ten finalists were then flown to perform three songs each at concerts for an array of VIPs in major Turkish cities, with the winner chosen by secret ballot from the crowds in attendance. The winner was promised a nightly gig (and monthly stipend) at a then-new club in Istanbul, The Oriental, as well as the chance to put out a 45rpm single, garnering any profits from sales. It was a national not-for-profit promotion and sales initiative that in turn helped spawn a consumer culture of record-collecting across the country.

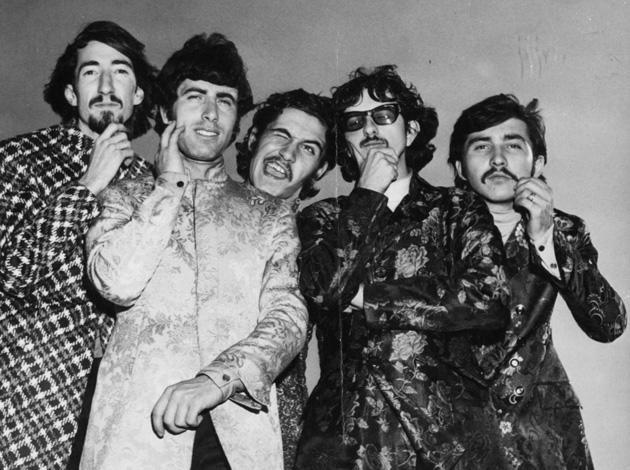

Between the riches and the glory, nearly every aspiring musician was moved to enter the contest. An awesome hodgepodge of styles was presented alla Turka, including peasant songs and nursery rhymes; the twist and the cha-cha; bossa nova, swing, and surf. Ironically, the winner of the very first Altın Mikrofon was Yldrm Gürses, a huge-voiced crooner whose dirge “Gençlie Veda” (Farewell Youth) was among the least contemporary-sounding songs in the competition. But second place went to a fresh-faced five-man combo called Mavi Iğıklar (Blue Lights), whose song “Helvaci” sounded like a eerie yet cheerful collision between doo-wop pop and belly-dancing music. When the single was released, it was a huge hit. The newspaper was pleased, writing of itself: “If Turkey has a band called Mavi Isiklar right now, we owe this to the Golden Microphone by Hürriye.”

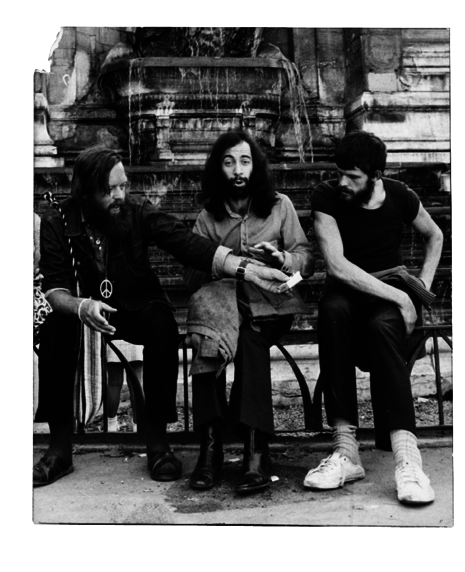

Over the next three years, Altın Mikrofon became an institution. New bands and new faces arrived on the scene, even as older groups splintered, traded members, mutated. The 1966 winner, Silüetler (Silhouettes) — an instrumental group obsessed with the Shadows — and 1967’s runner-up, Apağlar (Apaches, named for a Shadows song), combined to form Moğollar (Mongols), named for the conquering horde. Moğollar combined musicianship with an increasingly sophisticated take on what “Turkish music” should mean (and a deliberately unsophisticated idea of what a Turkish rock band should look like — where many of their contemporaries imitated Western hipsters, Moğollar made a point of wearing ethnic costumes and fuzzy white sheepskin boots).

The 1968 competition was the most epic yet. It would also be the last. Seven bands — thirty-two musicians and their families — set out by bus on a seventeen-day tour of the entire country, battling it out in the outer reaches of the Anatolian heartland. Moğollar placed third with “Ilgaz,” a love song for a mountain, while fashion plates Haramiler (Thieves) took second with “Arpa Bugday Daneler” (Pieces of Barley). The winner was T.P.A.O. Batman Ochestrasi, whose entry “Meselidir Enginde Daglar Meseli” (The Mountains Are Stronger Far Away) was a cheerful-sounding throwback to the Turkophone vocal groups and R&B acts from the inaugural contest of 1965.

But history, this time, belonged to the losers. The fourth-place finisher was a little-known group called the Erkin Koray Dörtlüsü (Erkin Koray Quartet). Though their entry, “Çiçek Dagi” (Mountain of Flowers), was danceable enough, it barely intimated the shape of things to come. Over the next decade, frontman Erkin Koray would create an unparalleled body of work, fusing metal, American blues, Anatolian folk, and Egyptian film music, all flavored with the smoldering fuzz of his electric guitar. (Koray was often referred to as the “Jimi Hendrix of Turkey.”) In 1974 he released his first studio album, Electronic Türküler. Türkü are folk ballads from the countryside, and on this album Koray achieved the comprehensive synthesis of his virtuosic talent for rock music and his consummate skill at arranging traditional songs. It was, you might say, the ultimate expression of the Golden Microphone aesthetic.

The Golden Microphone’s passing was mourned — another newspaper tried unsuccessfully to revive it a few years later — but it had achieved its goal. When Moğollar released its first album in 1971 — a stripped-down, wall-of-sound psychedelic fantasia — they called it Anadolu Pop (Anatolian Pop), and no one wondered that meant.