As recently as the turn of this century, the UAE seemed an unlikely new art center: its clutch of galleries tended to feature touristic watercolors, and the Sharjah Biennial was still a conservative, regional affair.

Yet this spring confirmed the Gulf state’s position as the dominant market center in the Middle East. Christie’s second sale of modern and contemporary art in Dubai exceeded expectations, selling ninety-two percent by lot. Abu Dhabi held an exhibition of the concept designs for a vast cultural quarter featuring four major museums, including the world’s largest Guggenheim. The UAE’s capital also confirmed that it will host a version of leading French modern and contemporary fair Art Paris in November 2007. Sotheby’s announced its move into the region. And the Dubai International Financial Center (DIFC) bought a fifty percent stake in the inaugural DIFC Gulf Art Fair, which hosted forty galleries, including London’s White Cube, plus a wealth of international art world luminaries in early March.

Some international critics are sniffing about a new art gold rush, and there’s no denying that these are boom times. The Dubai sale total of $9.4 million is, of course, miniscule in global art market terms right now — after all, Christie’s sold a Francis Bacon in London, the week after the Dubai sale, for more than Dubai’s 190 lots put together. But for the first time, Middle Eastern art appears definitively to be part of a global scene.

The regional market shows signs of maturing a little, too, with fewer outlandish hammer prices than at Christie’s first Dubai sale in May 2006. The hype is beginning to settle, and a core group of Arab modern masters — long popular among Lebanese collectors — is emerging, with Dia Al-Azzawi, Paul Guiragossian, and Chafic Abboud doubling their estimates. Syrian realist painter Louay Kayyali and contemporary calligraphic painter Nja Mahdaoui were particularly sought after this spring.

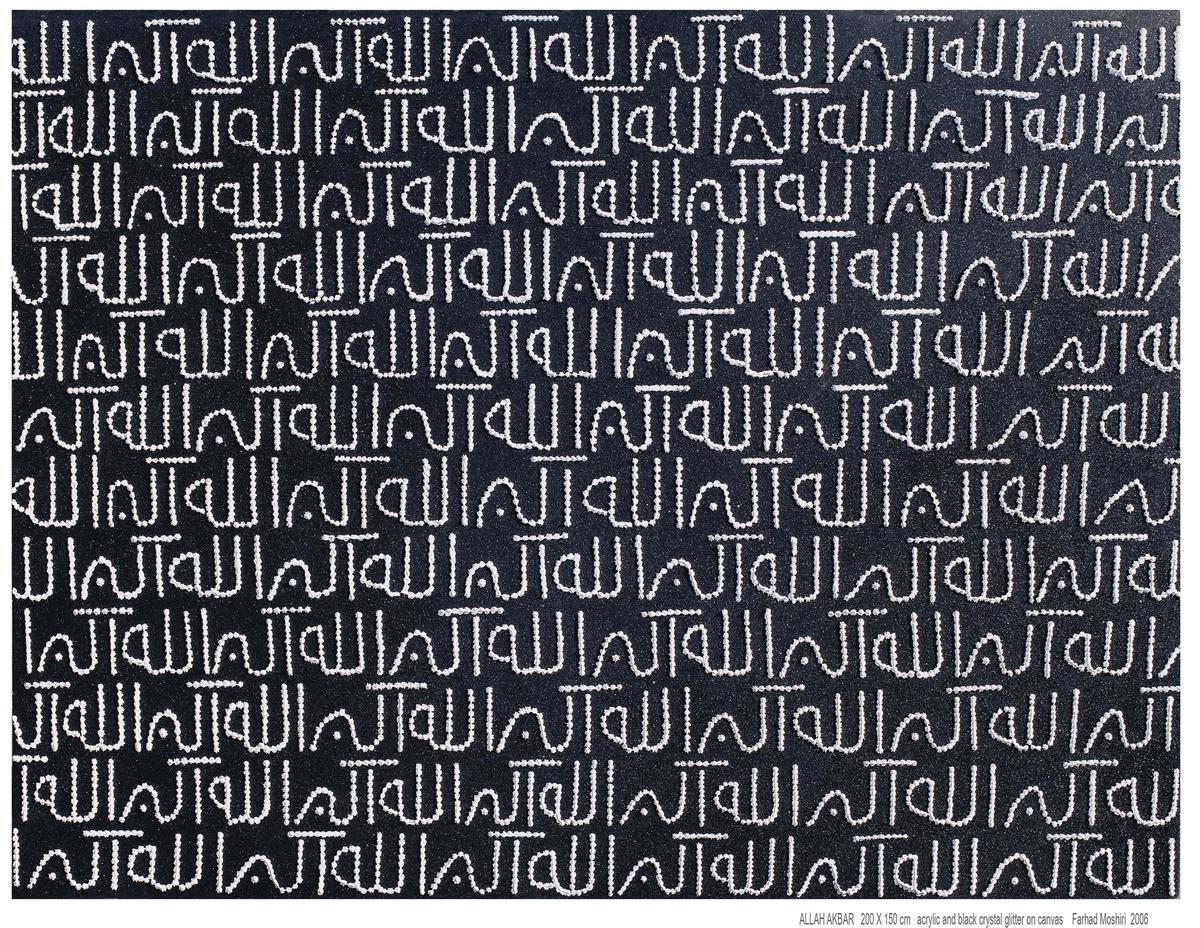

There was also strong interest in Iranian modern and contemporary art. Contemporary photography by Abbas Kiarostami, Shirin Neshat, and Shadi Ghadirian performed strongly, as did works by modern painters Massoud Arabshahi, Mohammad Ehsai, and Hossein Zenderoudi. A typically pensive work by contemporary photographer Bahman Jalali sold for $10,200 (estimate: $5–7,000). Farhad Moshiri’s work was once again the subject of frenzied bidding: Allah Akbar went to a UAE-based British collector for $102,000, four times its estimate.

Dubai is emerging as a center for all this activity. The UAE’s established Indian business community turned out in force, this time bidding on Arab, Iranian, and Western work as well as modern Indian art (which accounted for $4.1 million of the sale).

Front-row bidders included the minister for culture and other government figures; the success of Christie’s sales is central to Dubai Inc’s desire to become known for its sophisticated tastes as well as its high rollers. Local pride influenced fierce bidding on UAE artist Abdul Kadir Al-Raes’s Yesterday, which sold for $262,400 (estimate: $40–60,000), the top Arab lot in the sale. The Dubai market is atypical in the art world — though not atypical for Dubai itself — for the speed at which it’s develop ing and for its jumbled growth, led by the auction houses. There are new galleries opening each month in Dubai — including Meem (modern and contemporary Arab art), Bagash, and 1x1 Artspace (modern and contemporary Indian). But for now, the main centers of art production and criticism remain elsewhere.

Partly for this reason, perhaps, curators, critics, and auctioneers struggle to find an historical point of reference for this emerging market — although it has some similarities with the international “discovery” of Chinese contemporary art, Hong Kong’s emergence as a market center, and the birth of the now burgeoning market for Indian modern and contemporary art ten years ago. But for Dubai to become a center, let alone support a long-term market, it needs an arts infrastructure, and the diverse range of unpredictable and sometimes unruly stuff that makes up an art world — public museums, autonomous art schools, diverse communities of artists, a range of professional galleries, opinionated critics, curators, collectors, and so on.

As ever in its commercial history, Dubai has ended up benefiting at a time when its neighbors are suffering. Beiruti dealer Saleh Barakat is now partly based in Dubai. He says that Lebanese collectors want to consign and sell their work in the UAE, given the prices people will pay and the poor state of the Lebanese economy since last summer’s war.

Also, increasingly, Dubai is becoming a satellite capital for Tehran’s artists and dealers. Tehrani Fereydoun Ave will open a space in a 1950s townhouse in the Bastakiya area in April with a show of new photographs by Abbas Kiarostami, timed to coincide with the Iranian auteur’s retrospective at MoMA, New York.

But what does the UAE’s growth mean for artists? Some have seen prices escalate rapidly, effectively creating a two-tier market, with their Gulf auction price up to ten times higher than their local price (in, for example, Beirut or Tehran). Some find that their erstwhile patrons are being priced out of the market and question whether the “new collectors” are in it for the long term. Dubai-based gallerists such as Claudia Cellini (of The Third Line) and Ave say that some work may have simply been undervalued before — but that Gulf collectors also need to be savvy, and bid on works at auction that are true one-offs, that justify the premium.

Obviously, there are whole communities of artists — those whose subjects and styles are not so easily digestible in the Gulf, or who work in video and installation, for example — who rarely make an appearance. Contemporary Lebanese artists have been absent from the auctions so far. It remains to be seen whether the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi will be the first big museum in the region to buy large scale contemporary work; Frank Gehry’s design certainly begs for it. And the slick auctions and flashy fairs have little impact on the messy stuff of (innovative) art production, which remains chronically underfunded.

Regional dealers and collectors range from doom merchants, convinced that the paddle-happy bidders in the Gulf are somehow being duped into paying puffed-up prices, to those cracking open champagne.

Of course, it’s easy to be seduced as the hammer goes down on a Farhad Moshiri or a Khaled Al Saai, to the gasps and applause of a crowded, five-star hotel ballroom, in an upstart town that’s very much about the money. In a recent essay in The Village Voice, critic Jerry Saltz succinctly concluded, “Art still has a private inside and a public outside. It still exudes an alchemical otherness… The market is art minus the otherness. The rest is gossip.” Dubai certainly knows how to gossip. But can it find its inner otherness?