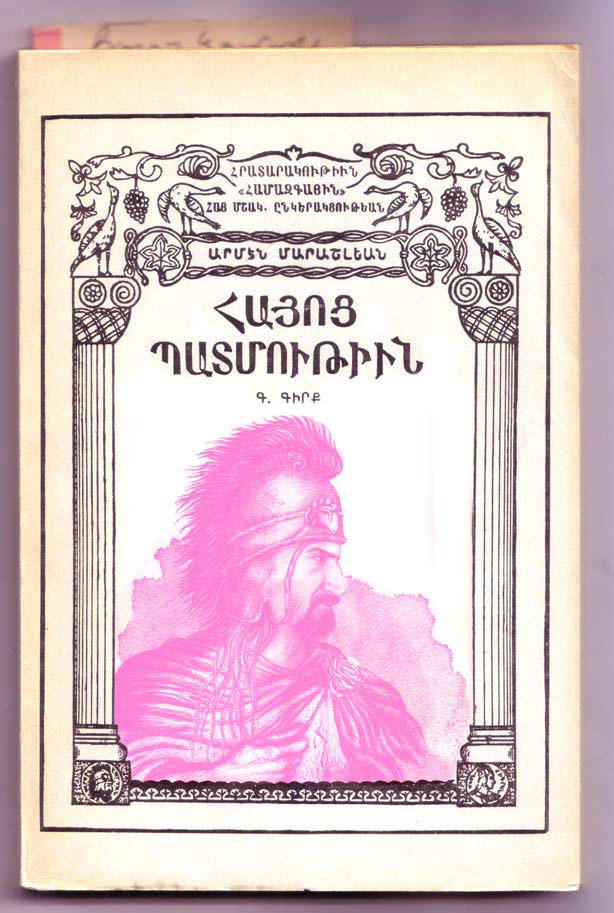

Cover design by Vartan Avakian. Illustration by Karim Farah

I was named after the great Armenian hero Vartan Mamigonian.

Also known as Vartan the Brave, Red Vartan, or alternatively, St. Vartan, Mamigonian was a descendant of a renowned and influential Armenian family. The Mamigonians were among the major nakharars, or feudal lords, in medieval Armenia. Many Mamigonians held the position of commander of the army, or sparabed. Vartan led the Armenians in their revolt against the Sassanid Persians, who ruled the eastern provinces of Armenia at the time.

So Vartan the Brave is a warrior’s name. His name is red and he is a saint. The cover of my third-grade Armenian history textbook featured an illustration of Vartan in his military costume holding a sword with a cross engraved upon it. The history textbook at school taught me a great deal about the brave warrior-saint. The story it told goes like this: Vartan Mamigonian led Armenian forces to fight the Persians in the battle that came to be known as the Holy Battle of Vartan, or Sourp Vartanants. The Persians were trying to convert the Armenians from Christianity to paganism. The two armies met on the shore of the river Tghmut in the Avarayr plain, not far from Mount Ararat. On May 26 of the year 451 AD, the 220,000-strong Persian army clashed with 66,000 Armenians under the command of Vartan.

Vartan and 1,036 Armenians were found worthy of martyrdom for fighting for, and finally falling for, what they believed. They preferred honorable death to servility. Because they perished fighting for the preservation of Armenian culture and identity, their defeat entered Armenian lore as a great moral victory. Conveniently, Armenians, like the French and their histoire, have a single term for story and history. And so, embellished or not, that was the (hi)story of the Holy Battle of Vartan, according to my third-grade book.1

One thing the textbook failed to explain fully was the meaning of the warrior-hero’s name, my name.

Who would have thought that Vartan — synonymous with glory and defeat and the tragic essence of Armenia — is in fact a Persian name? In Armenian, vart means rose. But its root is non-Armenian and can be traced back to the Pahlavi (middle Persian) vard/varda (värdä in Assyrian, ward in Arabic), whose root the great Armenian linguist Hrachia Ajarian finds in the old Indo-European urdho (thorny bush), which gave rise to the Avestan (east Iranian) word varƏδa: rose. The name Vartan was also used in Iran. There, it signified a rose-giver, a bearer of roses. Ajarian also sites the Armenian verb vartanal—literally, to become pink, which has since dropped from usage.

Red Vartan, then, turns out to be not so red, but rather pink in hue. Nevertheless, the Armenian Apostolic Church ordained him as a saint. On Vartanants Day, always celebrated on the first Thursday before Lent in February, an ode to St. Vartan from the Divine Liturgy of the Armenian Apostolic Church is recited:

Martyr, chosen Vartan, ordained captain of the host.

Many soldiers with thee were proven holy and brave martyrs.

Imbrued in their rose-colored blood, they inherited the kingdom.

They saw the heavenly light and were deemed worthy of the crown.

Armenians have never claimed that all days are Vartanants and all places Avarayr,2 but they believe that the Vartanian martyrs were victorious in dying for their beliefs. More than a thousand years later, the Persians themselves would raise the banner of Intisar iddam ala il sayf (the victory of blood over the sword). Adopting the Shia branch of Islam, they became champions of a culture of martyrdom centered on Imam Hussein, the grandson of the prophet, who fell on the fields of Karbala in the seventh century and became the patron saint, as it were, of the Shia faith. In many respects Vartan Mamigonian is the Hussein of the Armenians — or Hussein is the Vartan of the Shia.

Today, Vartan Mamigonian continues to be one of the most important icons linked to Armenian identity. Drawings of him are found in churches, in history books, on copper plates in Armenian homes, in restaurants — the infamous Varouj restaurant in Beirut, for one — and even on YouTube.3

The same textbook I once set my eyes on as a child, with that red illustration of the Brave Vartan on the cover, is still used in Armenian schools in Lebanon. The book is out of print, so the publishers, Hamazkaine, distribute black-and-white photocopied versions of it. So while Vartan in Hayots Badmoutyoun, or The History of the Armenians, seems to have lost his color, he has not lost his stature as the most important figure in Armenian history.

1. In 451 AD, Armenians’ cultural sovereignty was threatened from two sides: Byzantine Roman hegemony on their western flank and the Sassanid Persians to their east. Byzantium had convened an ecumenical council at Chalcedon with a central Christian leadership that tried to impose control over the Armenian churches, while the Persians were pushing their version of the ancient pre-Islamic religion of Zoroastrianism.

2. In comparison to “all days are Ashoura’ and all places Karbala.”

3. Recently, an Armenian-dubbed re-edit of the film 300 appeared on YouTube. The short film is entitled Vartan Bastermamigonian. The Persian King sends a delegation to get odorless Armenian basterma (a pressed meat, an Armenian delicacy) from the world’s most famous basterma maker, Vartan Bastermamigonian. But the Shah wants his basterma expunged of its odor. Vartan refuses to renounce his beliefs about the proper pungence of true basterma, and the Shah sends his armies against Vartan and his small but valiant Armenian army. Vartan’s army clashes with the larger Persian army. He dies bravely in battle, unbending in his allegiance to smelly pastrami.