The sign by the ticket booth reads, “WELCOME… Enjoy passing a good time by watching 1973, Panorama of the 6th of October [War] accompanied by the sound effects and music program.” And so it begins. Following the stream of earnest citizens onto the monument grounds, one is at once ushered into a mini-bazaar: gift shop, popcorn stand, mosque, and a studio with cardboard cutouts of ex-presidents Anwar Sadat and Gamal Abdel Nasser to greet you at the door. Inside the studio is an impressive rack of costumes (from the Pharaonic to the fellah) to choose from or, if you prefer the slicker Photoshop option, you may have your likeness inserted beside your favorite local actor or busty pop star against an improbable background. They weren’t kidding about showing us a good time. A little disoriented, it’s time for a stroll through the museum park. Constructed in 1983 with the assistance of Korean technicians, the museum is a monument to Egypt’s October 1973 Victory. And there he is, our omnipresent president, with words of endorsement writ large on a towering billboard, thanking men of the armed forces for their sacrifices for the nation, defending its honor, etc. Meanwhile, all around are families ambling in a space sprinkled with the monstrous apparatus of war — missiles, tanks, cannons — as freshly (spray) painted and unreal as model airplanes. Violently opposed to war, I feel anxious about the effect this ambiance must have on its audience.

As it turns out, I needn’t worry about this atmosphere stirring belligerent sentiments. They’re lovers not fighters, these irreverent Egyptians. And with an entrance charge of three Egyptian pounds (fifty cents US), this is merely an affordable Eid family outing and a feel-good venue, war-lite. Still, everything considered, there is something deeply disturbing about the sight of small children treating tanks as monkey bars (not unlike the sinister innocence of little boys play-fighting with water guns). This impression is not alleviated by the absurdity of a veiled relative scrambling up the armored vehicle to collect a child straddling its menacing projectile.

Within the main building is an uneasy truce between your standard military propaganda and installation art. There is a decent mosaic of Egyptian armed forces conducting battle, enshrined by a basin of plastic flowers — always plastic. Friezes depicting battle plans, the “great crossing [of the Suez Canal]” and acrobatic Pharaohs have all the definition of a much-handled soap bar. Across from them hang collages, bouquets of disembodied military heads floating on water, before nondescript battleships that look like something you might encounter at a downtown art gallery.

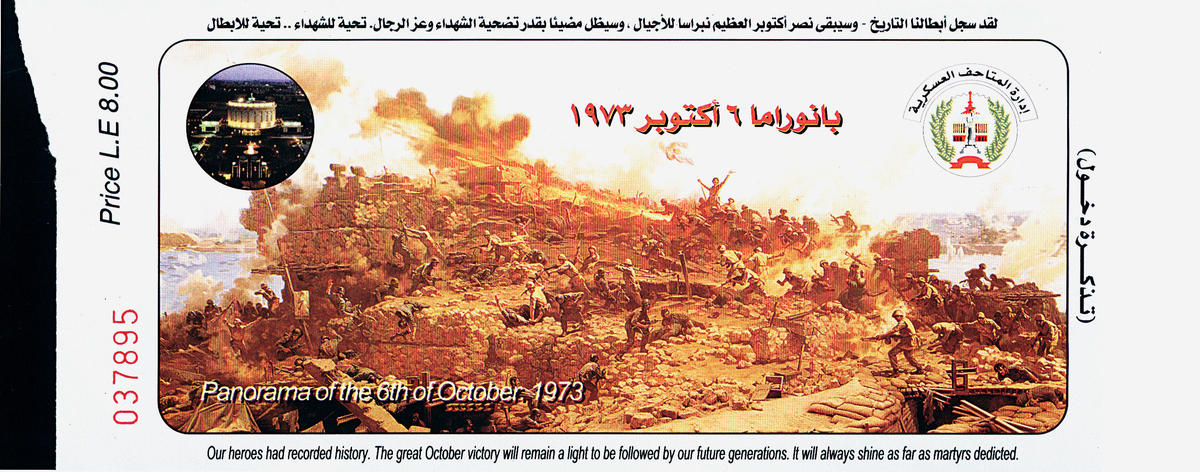

Finally, we line up for the main event: A painstakingly detailed and dizzying diorama featuring the mayhem of war-spent cartridges and soldiers strewn everywhere amidst explosive battle by land, sea, and air. A dramatic voice-over in the soap opera tradition narrates the events, blow by blow, accompanied by an over-the-top musical score. In one word, the music is bathetic; in two: oppressively sentimental. The platform turns at an excruciatingly slow lurch, granting us ample time to reflect on war’s unsavory glory.

Filing out, I find myself meditating on the function of such a seriously silly museum. Clearly intended to bolster that fragile construct, national identity, I wonder how much less self-deception there would be without self-image; how nationalism, a high-maintenance project, must be jealously protected and appeased, as with any insecurity. “The measles of mankind,” pronounced Albert Einstein, on nationalism. And are wars, inevitably, not the side effects of this malady of immaturity? In the final equation, these people don’t need “monuments” like this, but more public spaces, affordable parks, or arenas for less incongruous pleasures.