In the Tehran of my childhood, John Wayne was a household name. His swagger was adopted by tough guys in the street, his gun-slinging mimicked up and down the schoolyard. When we played Cowboy Bazi, which was all the time, Wayne was the original cowboy, the archetypal icon from abroad.

He was hardly the only one, of course. The 1970s were the golden age of Western idolatry in Iran. There were little stores where you could buy posters of Elvis and Sophia Loren, the Beatles and the Eagles, Farrah Fawcett and the Bionic Man. This was also when the Royal Kingdom of Iran acquired its third television channel. The new channel was called the Armed Forces Radio and Television Service, but mostly we called it the American channel. Instead of local sports, wrinkle-free news reports read in Farsi, and bedtime stories intoned by a doe-eyed woman with a sleeping pill of a voice, we had Starsky & Hutch, Donny & Marie, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, and much, much more — all delivered with the telltale twang of American English.

It’s hard to say what it was, but something about the sound of American resonated with us. The American accent combined a rubbery tongue with nasal exhalations, and we all imitated it. Only rarely did we say anything meaningful; mostly we just made up the words, intoning in a language that was neither English nor Farsi. We twanged as a posture, and that was meaning enough.

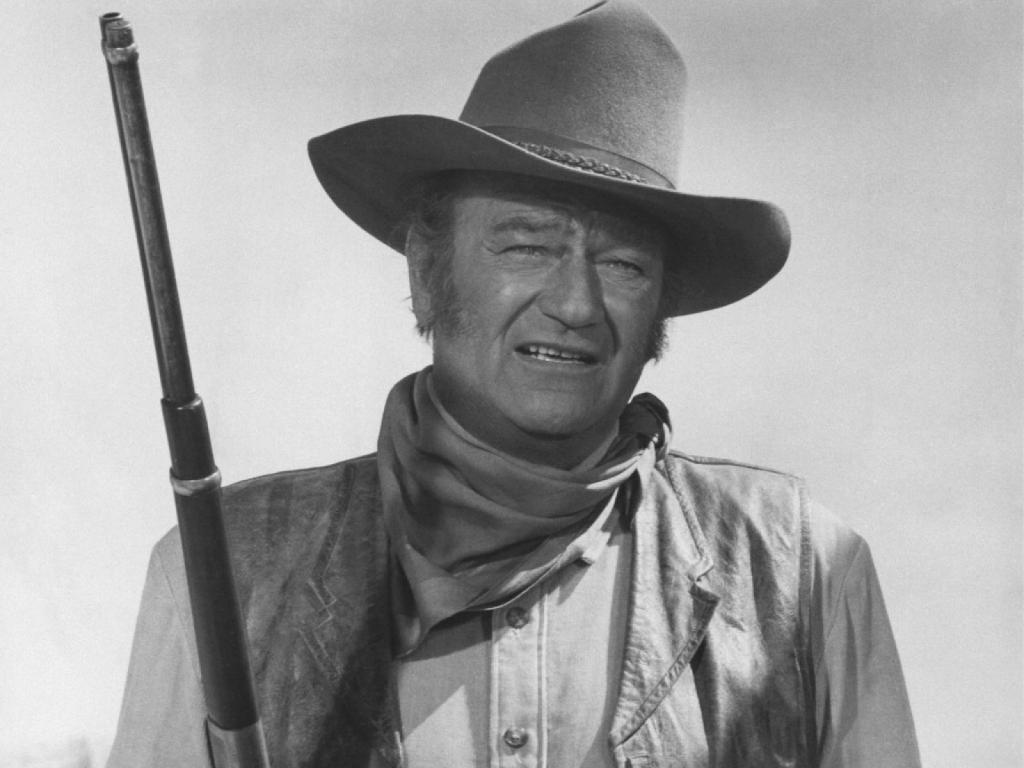

John Wayne’s Hollywood star began to rise over Iran in the late 1950s, but it was in the ’70s — when every weekend we could count on a cowboy show, from classics like Bonanza and Rawhide to the spaghetti westerns — that “John Vayne” became part of our everyday lives. Although he had shot to stardom with Sophia Loren when Legend of the Lost came out in downtown theaters, Wayne’s renown didn’t derive from his sexy co-stars or the excellence of his films or even our fascination with the accent. John Wayne came to us dubbed into Farsi, and it was the dub that made the man. He was not so much translated as alchemized by the wizards of Persian dub into a new alloy, a man who walked like a cowboy but talked like a dude from south Tehran — the kind of character you might meet in a kebab house, wolfing down a mountain of rice and a couple of lamb skewers, wiping his enormous mustache clean with the back of his hand.

Wayne’s tough-but-tender talk was delivered in the slang of downtown knife-fighters and hero-thugs, an urban subculture known as jahel: men with switchblades and a strict code of honor, not unlike the lonesome heroes of the Wild West. In keeping with jahel tradition, the Iranian Wayne and his gang insulted the honor of parents and family members alike, swore by Ali and Allah, and addressed each other with the most diverse, absurd, and expressive epithets they could find.

Every time an actor turned his back, the dubbers, freed from any obligation to sync with the image, would throw in some slangy insults — corpse-washer, stinking vulture — and during gunfights there was always time for jahel philosophizing. Ducking bullets, John Wayne espies a drunk on a porch and mumbles, “Lucky bastard, so totally oblivious to the world.” In Rio Bravo, Wayne addresses his partner Stumpy, an old lame prison guard, as Seedless Fig; and when he and Dean Martin start at a creaking sound, only to discover a stabled mule, there ensues between the sheriff and his sidekick a barrage of donkey-related swear words (in which Farsi is particularly rich). All this, with cheery disregard for the script and the authority of its creators.

Like many westerns, Wayne’s films unfolded in a space where the modern state — the omniscient, abstract rule of law — was still struggling to establish order over preexisting power and authority. John Wayne understood well the in-between space, being neither entirely a part of that order nor apart from it. Dressed in his red shirt and brown vest, his bandana around his neck, Wayne gazed boldly into the camera with a half-smile. That uneasy sincerity sealed a compact between him and his audience, showing his awareness of the camera, of the pose as pose. Rather than trying to cover up that crack in the fiction, as his contemporaries did, or ironizing it entirely, as our contemporaries might, John Wayne sat on the fence, managing to be not only two people, but also two types of people, himself and the cowboy, present and past in one body. His was a pose that had become itself without entirely erasing what it was before — an appealing prospect for Iranians stuck halfway between authenticity and modernity, wondering how to transmute one into the other.

The man who dubbed Wayne was a pharmacist by profession but also, like many of the other dubbers, an aspiring actor. His name was Iraj Doostdar, and he and his team comprised the genius club of dub. Theirs was not the only good dub in town, but it was the best. A different crew employed a similar style of dubbing to create Peter Falk’s brilliantly stuttering, goofy Columbo — a detective whose inner being expressed itself to the outer world only with great difficulty. (My friends and I could relate.) Years later, when I finally saw an episode of Columbo in English, I was stunned at how boring and flat it was. The Persian version felt so perfect; it was the original that came across as the bad dub.

The art of the Persian dub has an unexpected lineage. When the talkies first came to Iran in the 1930s, distributors continued to treat them like silent movies, interrupting the films with occasional “he said, she said” text panels in Farsi. But literacy was rare, so professional reciters would pace up and down the theater aisles, belting out reductive translations over the hawking of the sunflower seed vendors. Another strategy for domesticating foreign cinema was splicing. When a cowboy entered a saloon, for example, the doors swinging in his wake might fade to a popular and sultry singer belly dancing through a handkerchief-waving song-and-wriggle routine — not to fool viewers into thinking she was an Oriental stage act inside the local Texas juke joint, but to mash up that difference. Then the film would wipe seamlessly back to the western drama of the cheats at the poker table. No one complained about incongruence or bastardization — the downtown audience was quite happy with the pastiche.

Alex Aghababian, an Armenian Iranian, made the first of the Persian dubs while a student in Italy. The works of Italian neorealist directors were treated by Aghababian and a handful of other artistically minded Iranian students and sent back to Iran for distribution. Faced with difficult translatory choices, their innovative strategy was to sacrifice the words in favor of making the voices seem to belong to the bodies. The characters spoke nonsensical, rhythmical syllables, similar to the American twang we had affected as children. The sounds carried no literal meaning, but they matched Marcello Mastroianni’s lips perfectly, and in a way they resembled the kind of mumbled inward conversation people often have with themselves. By careful repetition of select sounds over the course of the film, distinct character traits emerged. The films were a hit back home, and by the time studios in Iran began to make their own dubs, there was an entrenched obligation to ignore the integrity of the original.

In fact, when they tried to stick to the original, Persian dubs of foreign films failed. Jerry Lewis’s extreme slapstick was amplified into unbearable silliness, and Hamlet’s existential crises poured out like complaints on a daytime soap opera, while the WASPy dryness of Katharine Hepburn dripped into Farsi like droplets of rose water — floral, wet, and sweet.

We were, it seems, much better at stealing than imitating. When the three soldiers in Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory are being led out to their execution—a tragic scene of prolonged silence and tension, in the original — the Persian dub has them pleading for their lives, pitifully, comically, in the vernacular of downtown Tehran. They beg to kiss the hands and feet of the colonel, to be his slave, his sacrificial kid. They implore him to “get down from his donkey” and spare their worthless lives. The disjuncture is breathtaking — as if Akira Kurosawa had given Robin Williams a free hand at dubbing Ran into English.

What made the best dubs so good was that they added another register, a meta-commentary that created and revealed subtexts in the films. One classic sequence takes place in The War Wagon, an average film with two big stars, John Wayne and Kirk Douglas, as reluctant partners. Douglas is a slick womanizer who’d shoot his mother in the back; he has just left the company of a pair of prostitutes to make a deal with Wayne. As with so many womanizers, there’s a touch of the dandy in Douglas’ obsession with his looks. Here he is wearing a shiny silk robe with an elaborate Asian dragon stitched on the back while Wayne, who is shaving, appears in a plain full-body undergarment with a holster buckled around his waist. Wayne explains that the gun is always with him because these days, you can’t trust anyone. It’s a throwaway line, the most obvious and predictable thing one gunslinger ever said to another. But then, as Kirk Douglas turns to exit, revealing the dragon on his robe, Wayne’s Persian voice offscreen whispers something like, “Well, well, check out the dragon.” Obviously not in the original, it’s a catty under-the-breath comment, a perfect subversion of the manly Hollywood cliché that preceded it.

Then, it’s Douglas’s turn. In his own room, he stops for a moment and ponders Wayne’s comment about trust. He is pensive and amused, as signaled by the raised eyebrow, the wrinkled forehead, the upturned lip. In the original, he is silent. But in the Persian dub, when Douglas turns and takes off his robe, his voice calls out in self-admiration: “Now that’s what I call a great body.” From these scenes will develop a very strong homoerotic relationship between the two stars and half-outlaws, who in the Persian version address one another as “my love.”

There was something uncanny about the dubbing, at times. Often the off-camera voices would seem to issue from a disembodied spectator rather than one of the characters; they said the sorts of things a viewer might say. Some secondary character was always commenting on John Wayne’s height, while a heroine’s sexiness was an occasion for a playful remark. As Dean Martin gets a shave from the delicate, razor-wielding hands of Angie Dickinson, a John Wayne–sounding voice moans, “Oh, I’d die to be hurting like your beard, dude.” It was as though a friend were providing a running commentary on the action while you sat watching at home — in the dubbed voices of the characters but not in their mouths.

Persian dub died a slow death in the late 1970s with the spread of corporate notions of ownership, stricter enforcement of copyright, a growing sense of loyalty to the original, and a swelling class of globally minded consumers who demanded nothing but “VO” (version originale). The revolution of 1979 hammered in the final unironic nail. When foreign films were banned and unavailable and the original dubs were locked deep in the archives, a few enterprising souls began smuggling in westerns and other films from Italy, Spain, or France. New technology made it easier to overlay a new dialogue track on VHS cassettes, and the result, still available on the streets of Tehran today, was bootlegged copies of Rio Bravo with credits and subtitles in Italian and flat, literal dialogue dubbed into Farsi.

The glory of Persian dub, while it lasted, was that it didn’t hide the artifice of film or its theatrical, scripted element. On the contrary, by showing that the original lines were just as made up as the dubbed ones, it seemed to acknowledge something even more postmodern: that social roles, like acting roles, depend on artifice, and that perhaps all cultural forms develop through acts of mistranslation. There were a thousand invented lines in every dubbed film, but they weren’t meant to fool anyone. Seeing the Persian dubbers get away with one more aside, one more joke, one more invented aphorism, brought us closer to the films in a conspiratorial kind of way. They made them ours.