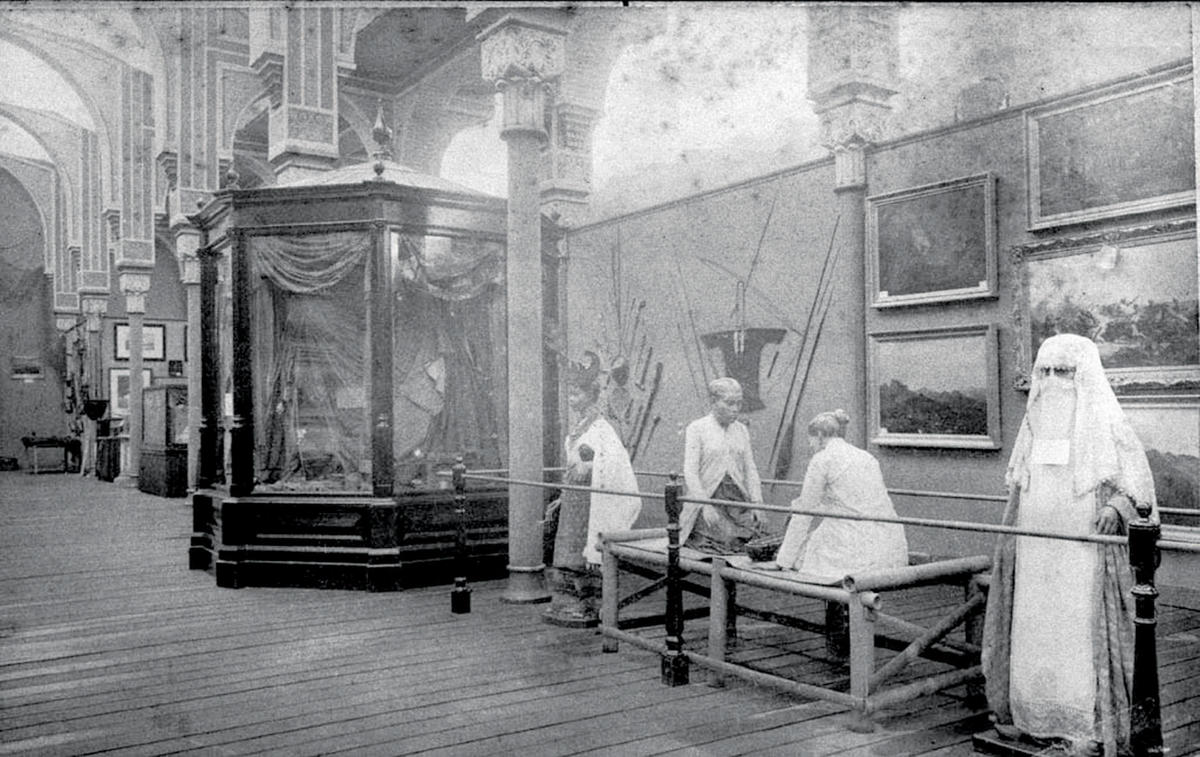

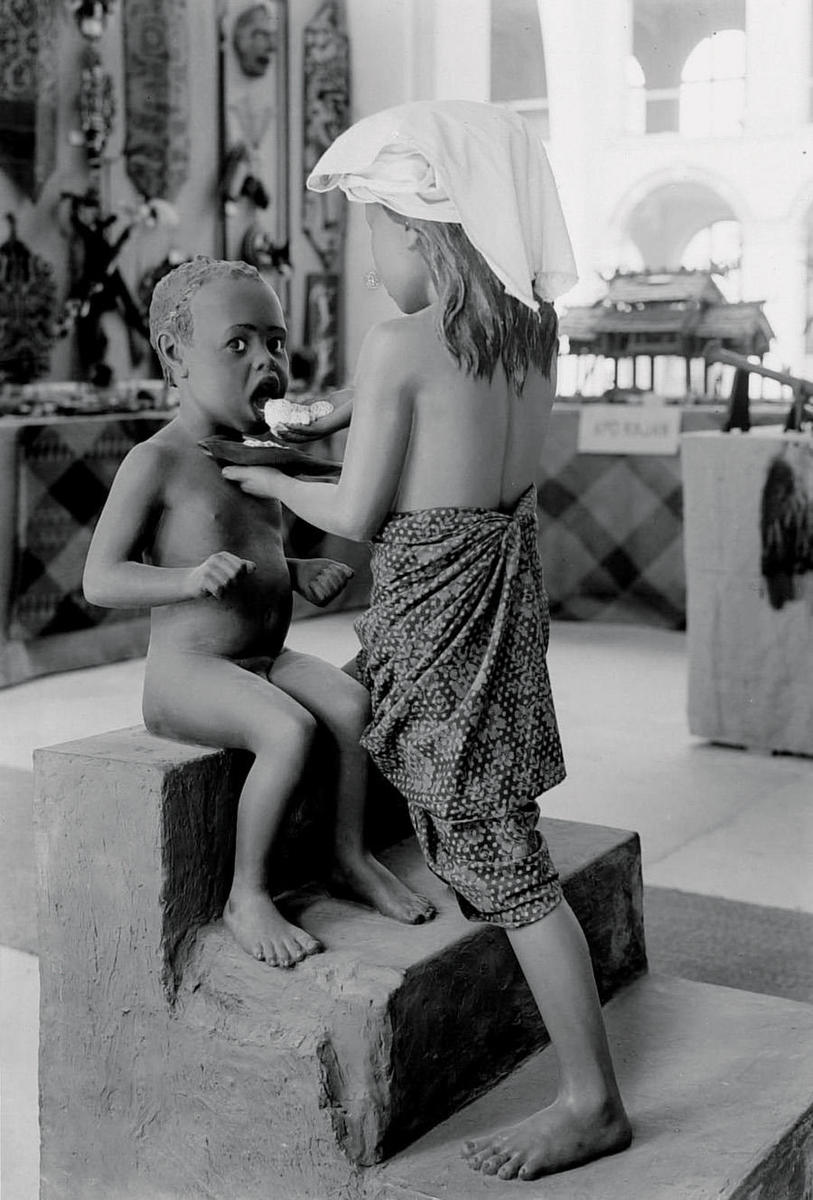

Soon after I became a curator at Holland’s Tropenmuseum, in 2001, I became aware of the emerging crisis of the ethnographic museum. These museums were originally created to present the ways of life of colonized populations — later renamed “non-Western peoples” — using objects, with no apparent historical or artistic interest, as static evidence of exotic lives. The traditional ethnographic museum presented cultures, to quote anthropologist Talal Asad, as narratives about “typical actors.”

These ethnographic museums omitted indigenous discourse in their staged displays; the people “on display” didn’t speak or think, they behaved. Now, thanks to cheap air travel, the real thing — firsthand experience of genuine exotics — is within easy reach of the European public, and ethnographic museums have lost their curiosity-value. Across Europe, they’re being closed down, merged with art museums, sometimes reinvented as centers for multicultural debate.

Though today’s museums desperately try to distance themselves from their essentialist past, they can’t escape their historic burden. Essentialism is woven into the present-day structure of the Tropenmuseum; the museum is divided into distinct regions, each with its own curator, exhibition space, and collection. Needless to say, in this compartmentalized world of cultures, only half the globe — or rather, the “non” half — is represented. Being a curator in an ethnographic museum means you have to position yourself in this particular historical relationship of the museum to its subject, the invented Other.

Today, the Tropenmuseum is trying to avert crisis by transforming itself into a cultural history museum, arguably part of a larger trend in which art museums are becoming more like ethnographic museums and vice versa (the boundaries between “art,” “popular culture,” and “ethnography” are increasingly blurred). The historical approach aims at a cross-cultural perspective that uses interdisciplinary tools. It also makes it possible for curators to take a critical stance toward the museum and the particular discourses in which it is rooted.

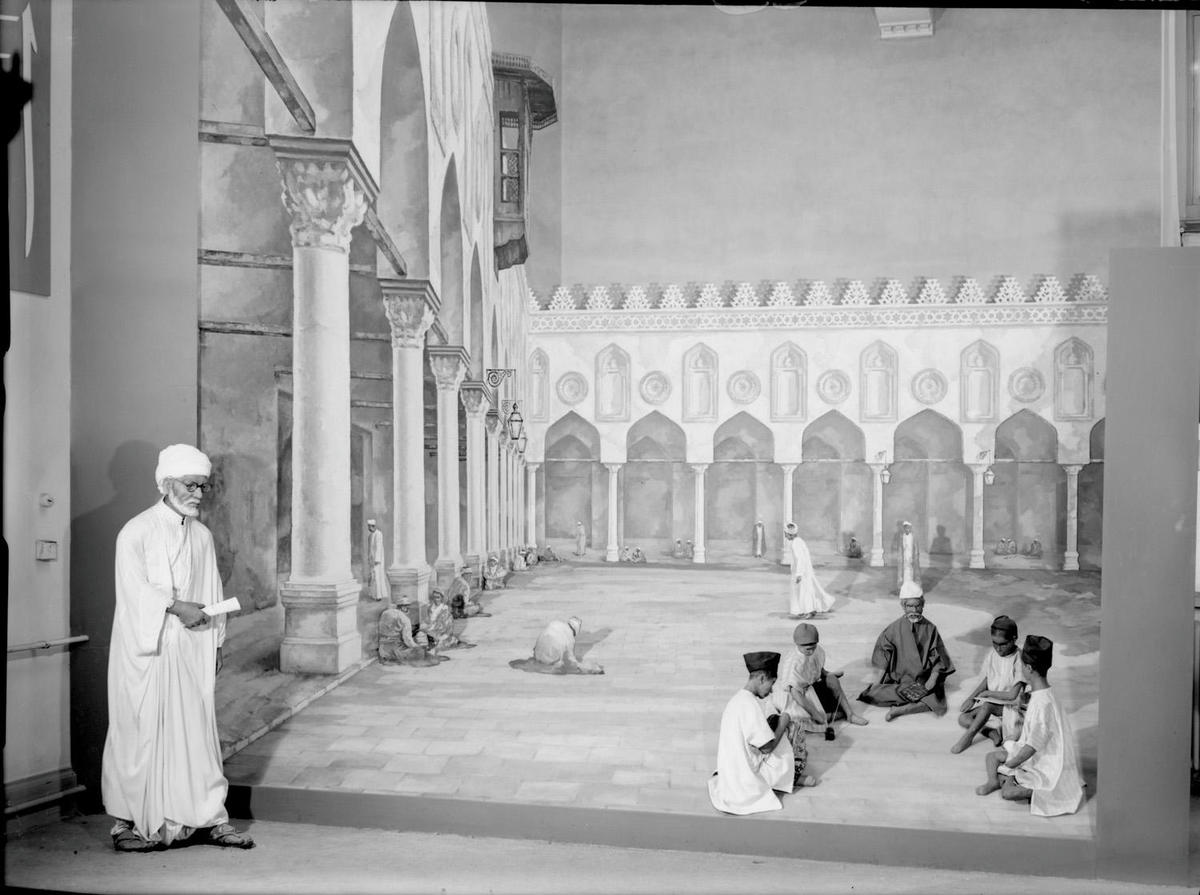

In a 2003 show called Urban Islam, for example, I tried to tackle the conventional ethnographic museum and its staging of cultures as necessarily silent (a sad practice that equally characterizes contemporary Dutch discourse on Islam) by presenting a vast array of opinions rather than fixed truths. But though my curatorial approach aimed to problematize notions of Islamic identity as an all-determining social factor, particularly in relation to current Dutch debates, the institution’s insistence on “Islam” as a rubric for the show may still have managed to replicate existing tropes.

The example of Urban Islam shows how decades of debating postmodern anthropology have left their traces; the old ethnographic museum no longer exists. The Tropenmuseum now presents artwork from all times and places and regularly features exhibitions that take a critical stance toward ethnography, colonialism, and the museum’s own history. But is that enough?

In 2006, I curated an overview of the works of visual artist Khosrow Hassanzadeh for the museum. The show focused on the artist’s own reflections on his work; almost all of the text panels consisted of his comments. Although the only text provided by the museum questioned problematic issues like the relationship between “inside” and “outside,” or the insistence on connecting artists’ origins to their work, visitor responses revealed that several people were upset by the gloomy picture painted of Iran. Much of the audience assumed that the museum’s main objective was to produce an image of the country rather than a unique perspective on an artist’s career. I actually don’t think the same show would have had a much different effect in an art museum — it has to do with an audience’s uneasy relationship to any art it considers foreign — but its location in an institution with a history of alienation certainly didn’t help. It also didn’t help that the museum’s PR department named the show Inside Iran.

In the long run, perhaps no curatorial approach — however critical or balanced — can rescue the museum formerly known as ethnographic, since it fails to address its fundamental flaw: the dichotomous mo del on which the institution itself is based. Today ethnographic museums have to acknowledge that the Other doesn’t exist outside the Western realm and that, consequently, ethnographic museums have never really represented other cultures in the first place; they represent Western culture and its outlook on the world. The Tropenmuseum can only redeem itself if it dissolves this distinction between the West and the rest.

I and many of my colleagues are aware of this dynamic and continue to challenge it, but museums as institutions are hard to hit. One reason is the lure of the toxic mix of consumerism and cultural representation. Museums, like other commercial ventures, need entertainment to boost visitor counts. And entertainment tends to be built on a foundation of conventions, stereotypes, and clichés. More fundamentally, dissolving the dichotomy between us and them would immediately bring an end to the independent existence of any museum devoted to it — in effect curating itself out of business.

Given this paradoxical situation, it would seem that curatorial strategies against the dualist worldview on which the institution is built are prone to failure. Real change is more radical than a mere shift in curatorial practice; the system that sustains such institutions itself must change. As long as the ethnographic museum functions as a distinct entity, I cannot counter-curate my way out. It is only possible to limit the damage; at times I believe I am successful. But until or unless systemic change occurs, I can only anxiously wait for the ethnographic museum to, finally, implode.