There’s a tone, a low-level nasal pitch, that can carry your voice across the desert quicker than a walkie-talkie, clearer than a satphone, and more urgent than a scream. There’s a whole system of sounds, of cries and songs and shouts, depending on the time of day and the type of weather and the sort of dune you’re standing on.

There’s Ru-ah, for dusk time at the top of a rounded dune.

And Mankoos, for midnight in the middle of a rippling erg.

And A’aobal, to keep pace across the sand or pull water from a well.

But Da’a is the ultimate Bedouin sound signal. Da’a means “Start a bonfire and send out the search party,” it means “SOS,” it means “Help.” And every family has its own version. Ours is Ya Delhamaai!, and Ya Delhamaai! is what my Aunt Ligaa keened out across the desert one afternoon around 1960 in a small tuft of oasis near Unguria in East Saudi. Her father had had to shake her awake at dawn — it was her turn to take out the goats. She was drowsy and dirty. This was in winter, when the sand is so cold it feels wet. In wintertime oases can spring up overnight around a puddle of mud.

It happened that one such oasis had appeared some kilometers northwest of the family’s season-camp. And so Ligaa headed out, smacking the goats and their kids and the billies on their asses with her precious bendy stick, a perfect whipping branch cut from the big tree in the village Endar. There were twenty-five or thirty goats, an entire family flock, save for one baby billy who stayed home so that his runt brother could have some milk-time.

Ligaa and her flock reached the grassy, swampy area in the late morning. She ate a dried cheese flatbread dipped in bright green semna and promptly passed out amid the rushes while the goats nibbled at grass and twigs and suckled at teats.

When she woke, it was to the smell of death.

A yellow-eyed mutt had stalked Ligaa and the goats all morning. When she fell asleep he set to work, first at the outskirts of the huddled, stupid flock, gashing and cracking and breaking the necks and backs and skulls of the littlest ones. Through all this racket, Ligaa slept peacefully, facedown in the sand, all manner of bugs crawling over her, into her hair and deep in her ears, where they must have deafened her with buzzing loud enough to mute a massacre. “I must have had a fever,” Aunt Ligaa told me one afternoon at teatime, nearly fifty years later. “I was sick for days and my mother had to burn it out with a hot rock.” She lifted up her leg to reveal a faint, vaguely rock-shaped scar along the sole of her foot. “Maybe that’s why the beast didn’t touch me? My meat was cooked and he had a preference for raw. Ha! Haha!”

She would have slept all the way into the night if a soft wet muzzle hadn’t nuzzled her urgently into waking. It was the mama goat whose kid had been left behind. The sun was on its way past noon, and the air stank of blood and shit and soured milk. There was no soft shuffling or pitter-patter of little hooves; even the mama goat had stopped sniffling and stood staring with her horizontal pill-shaped pupils. There was only the hissing of long grass in the wind and a long, labored dragging noise every few seconds.

Ligaa jumped up from her hidden bed in the rushes, the mama goat sidestepping nervously, almost topping over.

“It was disgusting,” Ligaa said. “Guts everywhere. The glutton had had his pick and ate only the full milk teats off the women and drank all the milk — and the kids and the men goats, he tore their throats out and left the rest.”

Ligaa could have cried, she could have fainted, she could have taken her stick and gone after the now sluggish wolf, but she did the smart thing, the right thing. My fourteen-year-old aunt let loose a mighty Ya Delhamaai! It bellowed out from the tiny blood-soaked oasis, like a foghorn in a sea of sand. The sound could be heard by every member of every clan in a ten-kilometer radius.

She waited, listening. Moments later, it was there on the wind: the clean sharp shout of her dad coming to get her, to get the wolf. No echo, just a pure message, a tone that said, whatever the time of day, “Stay there!” And then the shotgun shot so sharp it did echo, on the ground and the small hillocks of sand and on and off the dead goats and their blue and purple viscera.

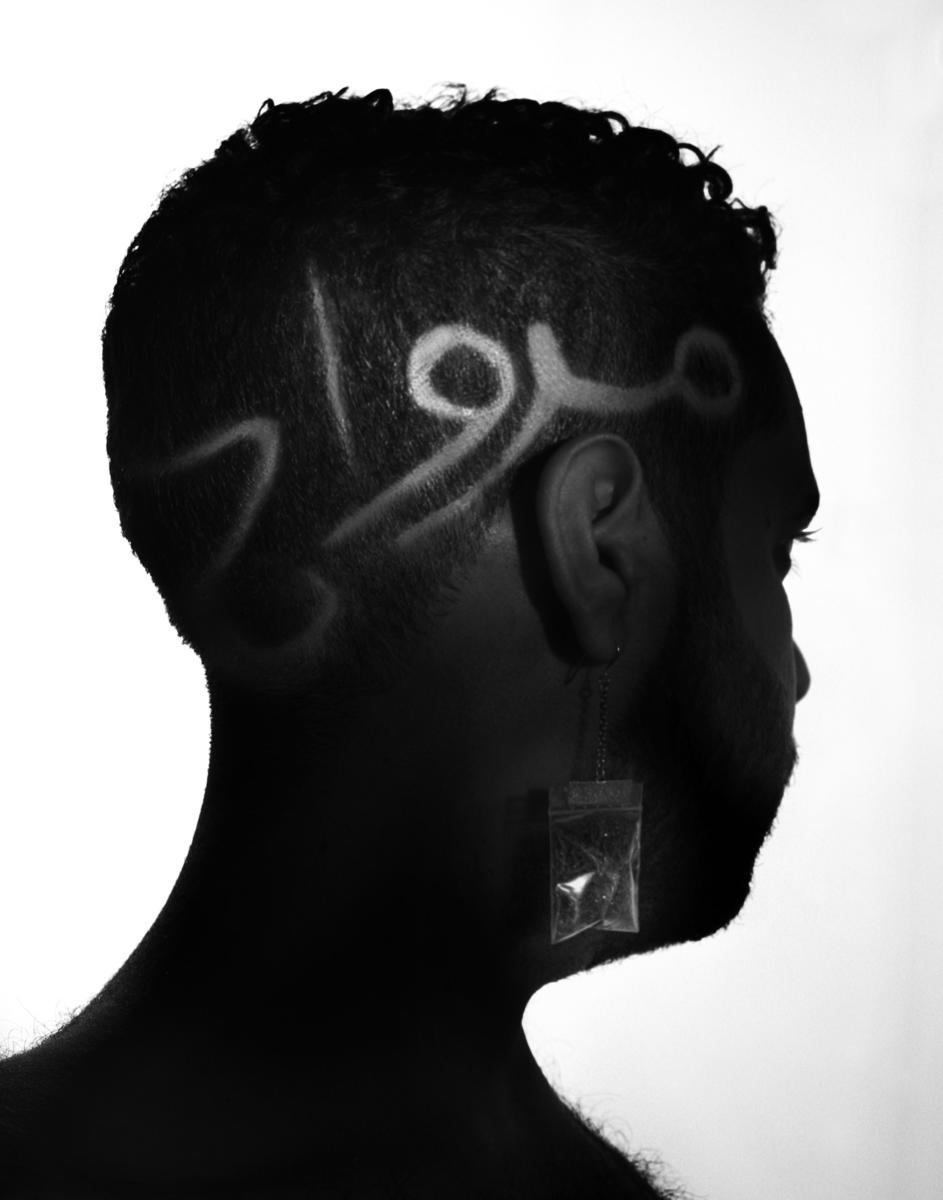

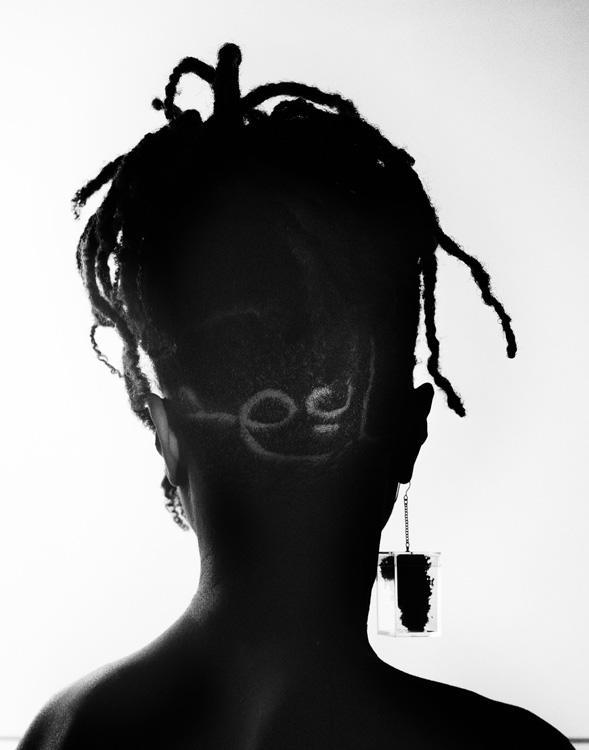

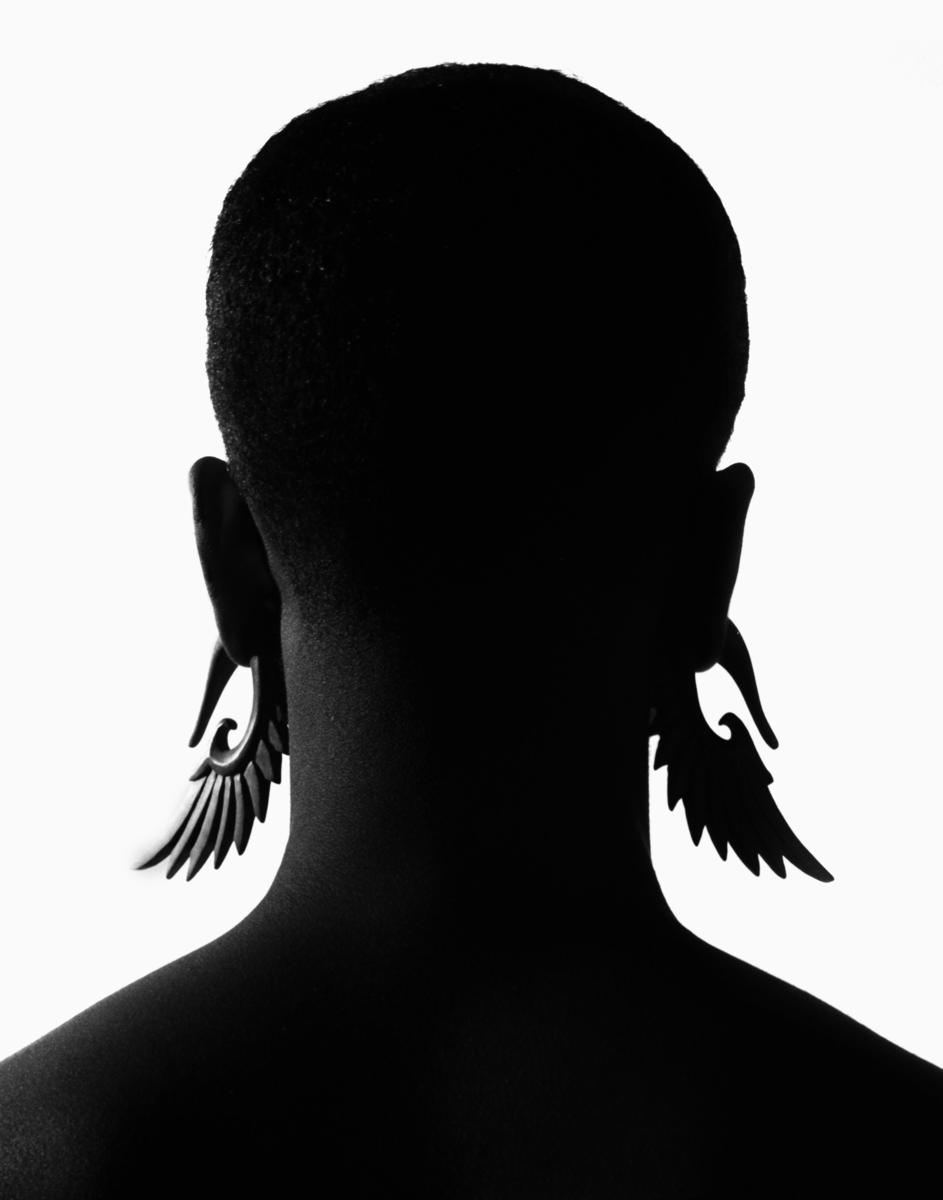

Hair: Fran Freeman

Styling and production: Telfar Clemens

Featuring, in order of appearance:

Khalid Al Gharaballi, earwear by Gerlan Jeans

Shaun Ross, neck dress by Avena Gallagher

Marc Brown, earwear by Gerlan Jeans

Monique McWilliams, earwear by Gerlan Jeans

Sanu, model’s own earwear

Telfar Clemens, earwear by Telfar