Tucked in the back of the University of Oxford’s cathedral-like neo-gothic Museum of Natural History, dinosaurs, fossils, and paleolithic worms, is the innocuous entryway to the Pitt Rivers Museum. A vast compendium of ethnographic and archaeological artifacts from around the world, the PRM is a touchstone of modern anthropology. It’s also the coolest place in Oxford, a clutter of dusty vitrines crammed with objects both magnificent and mundane, tagged with labels in the founder’s own minuscule cursive and set on top of stacked drawers, all full of equally strange things.

Museum guards wander through this glass and mahogany jungle dispensing wind-up flashlights and genially overseeing the mayhem of excitable school kids running around in search of shrunken heads. They also point out objects of particular interest — on my last visit, a tiny pair of dancers, figurines from early 1900s São Paolo. Their top halves are made from the heads and thoraxes of large mosquitoes, while Barbie-style legs poke out of the bottom of their stiff, lacy dresses.

There seem to have been few selection criteria guiding the PRM’s collection, other than most of the objects having been made by human beings. (The study of man prompts some curious archival impulses; see also the Peabody and the Musée de l’Homme.) The museum’s founder, Lane Fox — or Lieutenant-General Augustus Henry Pitt Rivers, as he was later known — intended his collection to demonstrate the evolutionary development of civilizations and the “phylogenetic unity” of the human species. If artifacts of the same type were placed in close proximity, even the most amateur anthropologist would be able to spot human progress — culminating, of course, in the West.

But the sheer randomness of the collection confounds this positivist intent. The “Toys and Games” cabinet contains footballs made out of plastic bags, rubber bands, and condoms from all over Africa, as well as polo balls from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. Arrangement according to theme means that you get to spot a hundred different variations on the same object, spanning centuries and the entire globe. The contents of “Keys and Locks” encompasses ornate sixteenth-century European constructions, complex wooden bolt mechanisms from Nineveh, and pronged wooden padlock keys from Bahrain. While many cultures had whistling arrows, the Japanese attached special crescent blades to theirs, the better to sever the rigging on enemy ships. More countries than you might think had bagpipes; everyone made charms to ward off the evil eye.

The provenance of most of the collection is as random as the objects themselves. “Forms Suggested by Natural Shapes” includes a “natural stone resembling a monkey’s head” found in Marston, near Oxford, in 1900. PR himself bought the bulk of his contribution at auction, but many items were deposited by anthros returning from overseas and even by museum employees. A bong made from a Coca-Cola bottle purchased by a curatorial assistant on Oxford’s Cowley Road a few years ago is displayed in “Smoking and Water Pipes.”

Some artifacts are almost certainly the consequence of overeager tourism. A painted black wooden jackal from Ancient Egypt looks like something knocked out quickly by a Cairene souvenir seller when he saw the proverbial sucker coming. Captain Cook’s second South Seas voyage also appears to have been one big shopping trip, with the natives taking the explorers for quite a ride. As a museum placard explains, the voyagers were surprised to find the price of things changing drastically from one day to the next. “Tools” contains bamboo knives from Vanuatu, Melanesia, that are said to have been thrown away after their first use — leaving one to imagine the donor, the intrepid Reverend Coddington, scrabbling through the village bins.

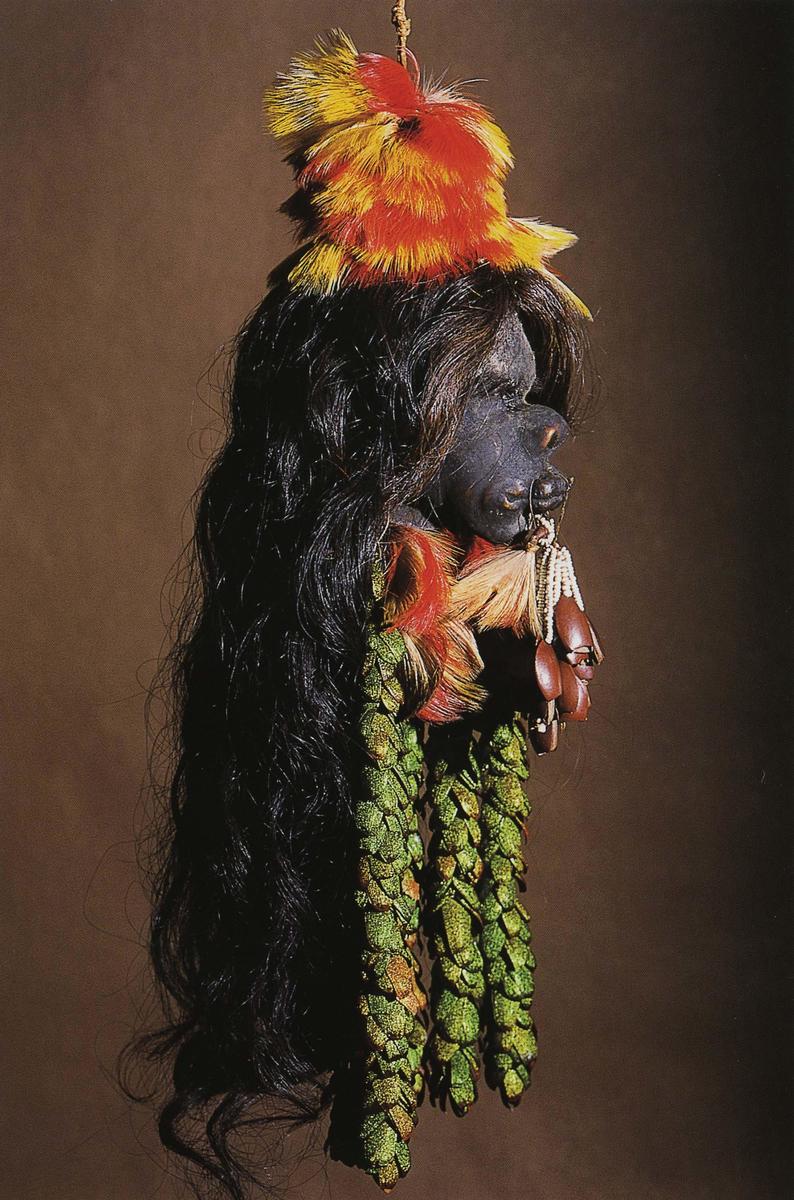

For the most part, the dubious origins of some of the older objects evoke nineteenth-century anthropologists participating in a colonial barter game. The PRM proudly includes fake shrunken heads among the real ones, as if to suggest that their significance lies in their makers’ recognition that their traditions were turning into collectibles (though the fakes are flagged, as if to reassert the discernment of the collectors). Some trophies arrived in Oxford via direct acts of colonial plunder, including treasures from the sacking of Benin during the “Punitive Mission” of 1897 and a choice ostrich fly whisk belonging to a Nuer prophet, requisitioned in Sudan. (The British authorities detained its owner in 1928 as part of a crackdown on Nuer prophets, but he escaped, minus his whisk, at which point the governor of the region relayed the object to the museum.)

The PRM’s colonial heritage and paternalistic bent is evident throughout, reflective of the prevailing orthodoxy of the times. But the founders’ wincingly un-PC curatorial instincts may be partly redeemed by the fact that the collection is not limited to the “outside.” There are numerous objects of British origin, among them drawerfuls of braided wheat decorations and magic charms from Oxfordshire, including “slug on a thorn,” a mollusk impaled on a thorn and pickled, which was once supposed to ward off warts.

The PRM is a glorious jumble of tat and splendor, like a flea market for the world. There are essays to be written on any number of its collections, including the desert-loving Wilfred Thesiger’s entire photographic archive; Berber trepanning tools; cases of model ships; little boxes of “asses skin glue used as a drug”; and more. PR wrote of his museums (there is another in Dorset) that “if no more good came of it than to create other interests, which would draw men’s minds away from politics… good would be done.” The effect is exactly opposite, at least for me — but thanks, Foxy.