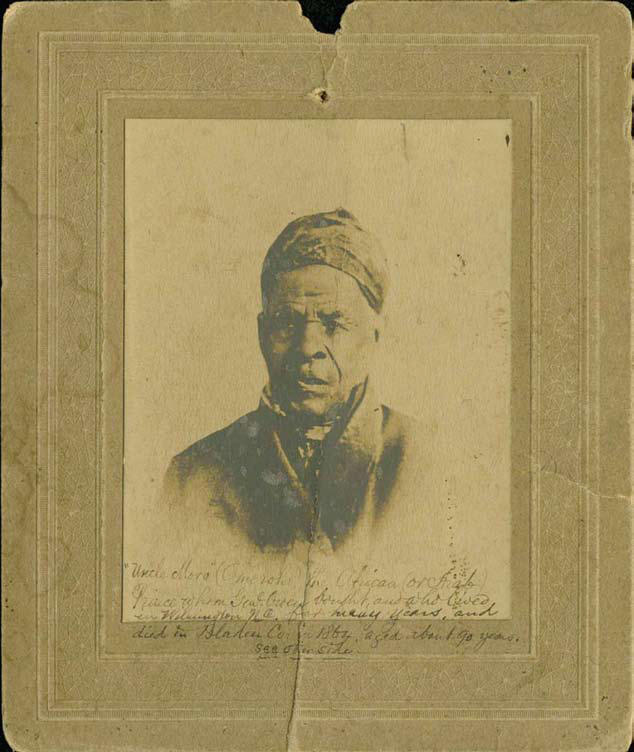

It wasn’t easy to sit staring at the camera for twenty-odd minutes, unmoving, while the daguerreotype coalesced into a recognizable form. That was true for most anyone, let alone an African legal scholar from an aristocratic Muslim family who was also, at the same time, an American slave and Christian convert. Omar ibn Said, the self-styled Prince Moreau of Fayetteville, North Carolina, was a study in contrasts, a composite even here: his artfully arranged clothing (scarf wrapped around the head just so, collar puffed and starched) belies the doubtful, nervous look in his eyes. He looks no more at ease in an ambrotype made decades later. Ensconced in a gaping black overcoat, his chest appears almost concave, matching his decidedly down-turned mouth, puckered in a way that suggests the futility of any effort to pose.

Said was only one of a number of purportedly princely West African men enslaved in the antebellum American South. He was also literate in Arabic and famous for it, at a time when it was illegal for a slave to be literate in English in North Carolina. In this, too, he was by no means alone. The Africans in North America included literally innumerable West African Muslims, many of them capable of reciting the Qur’an by heart, some of them able to write it. And yet by the operation of chattel slavery they became residents of a largely illiterate society of white yeoman farmers who treated them as little more than animals. The periodical literature, diaries, and news reports of antebellum America register the perplexity of Southerners who observed slaves “pray[ing] five times a day, always turning their face[s] to the east,” and witnessed them etching obscure characters into the dirt with sticks during short breaks from cotton-picking. Some of these slaves would go on to compose interesting narratives of their bondage and their freedom, but white Southerners, still misreading the signs, often numbered these compositions in reverse of their narrative order, thinking them nothing more than strings of cryptic symbols. After their momentary vogue among ethnologists during the late nineteenth century, these Arabic-language slave writings often wound up in the recesses of Southern libraries and the basements of Southern churches, until scholars rediscovered them, and began to take them seriously, in the 1980s.

“The Autobiography of Omar ibn Said” was composed over a period of months in 1831. Mary Owen, wife of North Carolina governor John Owen, had given Said a book of quarto paper and a pen with which to set down the story of his life — fifteen pages, front and back. Said’s handwriting was contradictory, almost schizophrenic, lean and precise, then thick and clotted. A heavily inked crosshatch pattern was a recurring feature, often marking the end of a passage or surrounding a prayer; the dense shapes seemed almost architectonic, and Said encouraged his readers to interpret them as such — paper renderings of his (entirely fictitious) West African palace. At other times, he would aver that these drawings represented not the palace itself, but rather his royal family’s coat of arms.

The story of Prince Moreau made extensive use of these patterns of letters, drawings, and dashes to evoke his cunningly composed identity. Reconstructing the story of his capture and enslavement, Said added the stuff of legend to his decidedly more pedestrian personal history. It was a case of mistaken identity, the aristocrat confused with a commoner, with commerce. Yet despite his assertion of a royal bloodline and the indignity of his circumstance, it didn’t occur to him to go home to Africa. Almost the opposite — the text of his memoir flatters the Owen family to the point of obsequiousness. He showers them with bismillahs and stops his narrative several times to praise their hospitality. As descriptions of slavery go, it seems almost surreal. But then Said presented himself not as the Owens’ slave, but as their guest, a noble visitor from a strange land, laid low for a time but now restored to his dignity and station — a prince who, apparently, had it pretty good on the plantation.

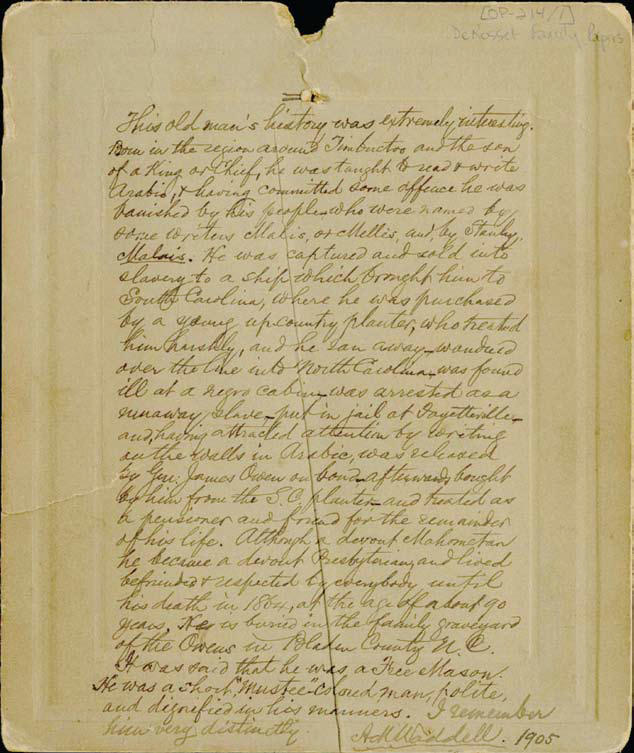

Said had come to the attention of the Owen brothers in or around 1810, when he turned up in a Fayetteville jail. The “peculiar”-looking man, already in his forties, attracted notice throughout the county, not least for the facility with which he wrote in a “strange language.” Covering the walls of his jail cell with piteous coal-composed calligraphic petitions begging to be released, Said’s holding pen quickly became more of a performance space. Many local citizens visited the jail to see him, and he became a favorite of area schoolchildren, who “fitted up a temporary desk, made of a flour barrel,” and amused themselves by watching him write “from right to left, in what was to them an unknown language.” At some point, a few weeks into this curious ordeal, it was determined that the man who called himself Prince Moreau was writing and speaking in Arabic — a perceived novelty that made him only more of a celebrity. Governor Owen purchased Said from his former owner for one thousand dollars, eventually giving the slave to his brother James, an ardent bibliophile whose private library was said to be one of the largest in the US, rivaling Thomas Jefferson’s.

Said became something akin to the spectacular centerpiece of James Owen’s extensive library. He was given materials and space for study among the books, and he was showcased in a separate dwelling adjacent to the main plantation house, complete with its own slave. Said hosted a steady stream of visitors who came to hear him recite suras from the Qur’an, as well as Psalms and other Bible verses translated into Arabic. Said was said to be able to recite the entire Qur’an from memory, even late in his life, and it is rumored that he had transcribed a copy for himself; rumors also claim that the book was buried with him, at his death in 1865 at the age of ninety-four.

Personally conflated with the culturally confused fragments produced by his pen, he was called in one 1847 article a “superior remnant.” Was it not, the author asked, “quite as remarkable to find an Arabic scholar under such a guise as to find a scrap of antiquity deposited on the moldering shelf of some ancient library?” Southerners thought of Said’s body as something that could be read like a book, his fingers echoing the curvatures of Arabic characters, his fancy overcoat a living, breathing book jacket. Not unlike the Bibles and other religious texts popular in antebellum America, texts in which large maps of the Holy Land were sandwiched between Psalms in order to insinuate scriptural stories into real, lived geopolitical history, Said provided a multisensory experiential encounter with the text and context of the Qur’an in a safely Christian setting. He was the medium and the message both, and he became quite good at the role.

The self-appointed mascot of the First Presbyterian Church in Fayetteville, Said would saunter into Sunday services dressed in a long, flowing robe and slide into a specially constructed, thronelike chair in the front of the pews. He was both talisman and model for the imagined success of missionary incursions into Africa, immensely popular among the Southern Presbyterians in China and the Middle East, with whom he had contact. Said also maintained an international correspondence with a network of other Arabic-speaking slaves. Among the first to read Said’s autobiography, Lamen Kebe was one of several former slaves with whom Said maintained contact after Christian colonization societies paid for their repatriation to Liberia. Kebe had been apprehended around 1804 during a trip to Timbuktu to buy paper; he was captured by slave traders at night and awoke to find himself in fetters. Thirty years later, the literary bent that indirectly caused his capture became his ticket to freedom — of a sort. Missionaries working in Africa, who figured that the highly educated Kebe would make a great proselytizer, bought his passage to Liberia in 1835, giving him good reason for a shotgun conversion to Christianity.

On similar grounds, some have questioned the circumstances and sincerity of Said’s conversion to Christianity, but antebellum North Carolina could have easily made a believer out of someone with Omar ibn Said’s talents. During John Owen’s brief tenure as governor — about the time that his wife was urging Said to get his story down on paper — he responded to an antislavery pamphlet written and published by David Walker, the son of North Carolina slaves, with Old Testament fervor. Decrying the tract as “totally subversive of all subordination in our slaves” and sensitive to the “awful peril” the whites of Fayetteville would be subjected to if the slaves became rebellious, Owen supported draconian penalties to curb slave literacy in English. It was quite common for slaves caught in the act of writing in North Carolina and neighboring states to have their hands or fingers amputated as both punishment and preventative measure. Daniel Dowdy, a slave in Georgia, explained that the first time a slave was caught writing, he would be whipped; the next time, “they cut off the first jint offen your forefinger.” If they caught you again, they would take the entire hand.

Pinning proclamations declaring his desire to remain with the Owens to trees all over the plantation, and beginning many of his texts with the entreaty “O ye people of North Carolina, O ye people of South Carolina, O all ye people of America,” Said crafted himself as an Arabic prince rather than an African slave, in a stunningly effective song and dance that sutured the threat posed by his exoticism to the solid, reassuring foundations of the Presbyterian Church. It was enough to keep his fingers off the chopping block despite his copious correspondence. Neither his “delicate,” “effeminate,” “well-tapered” fingers nor his outsize personality saw any censure or severance, making it pretty clear who had the keys to the pen.