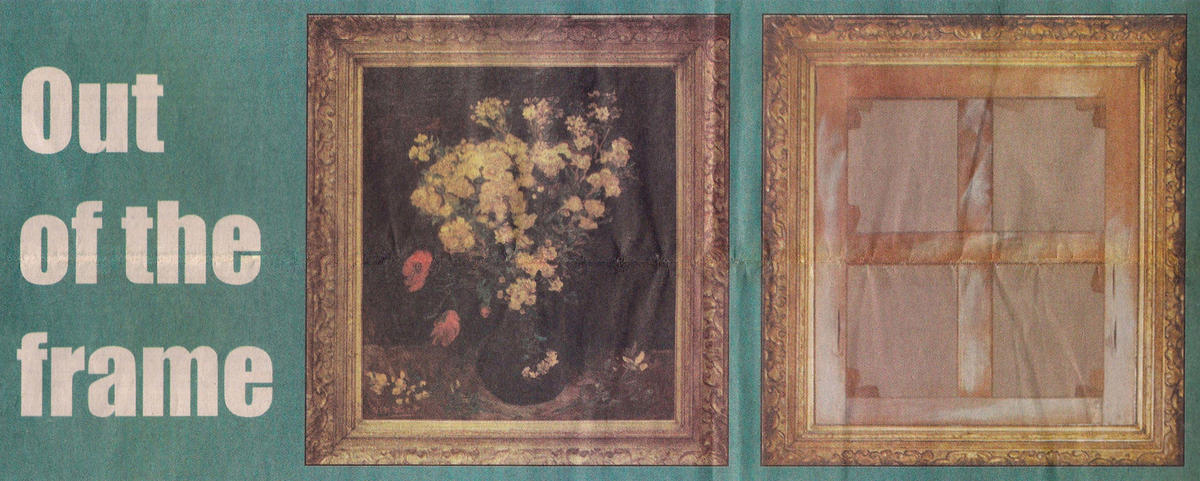

“The painting is a piece of shit,” said Mohsen Shaalan, head of Egypt’s Fine Art Sector. “Its only value lies in the signature.”1 The painting in question is, of course, Vincent van Gogh’s Poppy Flowers (1887), or Zaharat al Kheshkhash, a name familiar to anyone following the story of the work’s dramatic theft last August from the Mohamed Mahmoud Khalil Museum in Cairo. While hanging in plain view, it was largely invisible — yet another dusty painting in a museum nobody visits in the first place. The question of its supposed worth remained latent, too. But within the first few days of its theft, the painting’s price tag — widely reported at between $50 million and $55 million — had become a favored subject of discussion among the local media — a dollar-sign-shaped exclamation point appended to the crime. And still, in spite of his stated disdain for the iconic poppies, Shaalan may have been the first public figure of note to express any opinion concerning the painting’s value in nonmonetary terms.

Certainly, the issue of how to assess an artwork’s worth has been on Shaalan’s mind. The disappearance of Zaharat al Kheshkhash may cost him his job and has already landed him a sixty-day sojourn in jail and a three-year prison sentence (pending appeal) on accusations of negligence. In the face of his newly precarious fate, Shaalan has found it essential to embrace a strategy that is both original, given the context of the scandal, and as infinitely predictable as the extension of emergency law: redefine oneself, in the media-savvy manner perfected by Madonna, as an “artist first and a bureaucrat second.”2 Allow me to present that revered and reviled, inextricable and unavoidable figure: the artist-bureaucrat.

In the wake of its disappearance, the rather somber oil painting of red and yellow flowers in a vase has swiftly become the most famous work of modern art in Egypt. Its now pathetically empty frame became, for a time, a favored visual pun of newspaper cartoonists. But perhaps most compellingly, it has provided a lens onto what has up until now been breathtakingly opaque, focusing the public’s attention on the internal workings of the usually news-unfriendly Ministry of Culture and the machinations of those individuals vying for power within.

Ostensibly because they lack substantive leads regarding the perpetrators of the crime, police, prosecutors, and the media have focused instead on the issue of negligence. The museum’s lax security standards were exploited by the thief whose tactics (slicing the piece out of its frame) and timing (the middle of the day) suggest a complete and utter failure on the part of museum staff. It has been widely reported that only seven of forty-three security cameras were working that day, and that the museum guards were notably absent.3 (To add insult to injury, the painting had been stolen once before, in 1978, and although it surfaced two years later and was authenticated by unnamed “specialists,” the work hanging in the Mahmoud Khalil was long rumored to be a fake.4)

Shaalan, blamed for the situation, claimed that he was the fall guy for Farouk Hosni, Egypt’s Minister of Culture, and a very public exchange between the two career bureaucrats has ensued. Shaalan, an owlish-looking fifty-nine-year old, set the tone; his early, sharp jabs at the Minister quickly earned him media attention: Hosni’s true talent, Shaalan claimed, lies in selecting fine silk neckties and showboating for the press5; Hosni insults the sensibilities of the Egyptian people by sailing to work every day on a private yacht6; and the money Hosni squandered on his bid to be elected the next head of UNESCO (a position he campaigned for vigorously yet unsuccessfully in 2009) and on his expensive pet projects (including the renovation of the Egyptian Museum and development of a new Museum of Civilization) could have saved the stolen painting and many of Egypt’s museums in the bargain.7 In lashing out at Hosni, Shaalan has launched his own campaign of personal redemption, couched in a language and ethos informed by his long experience in the ministry.

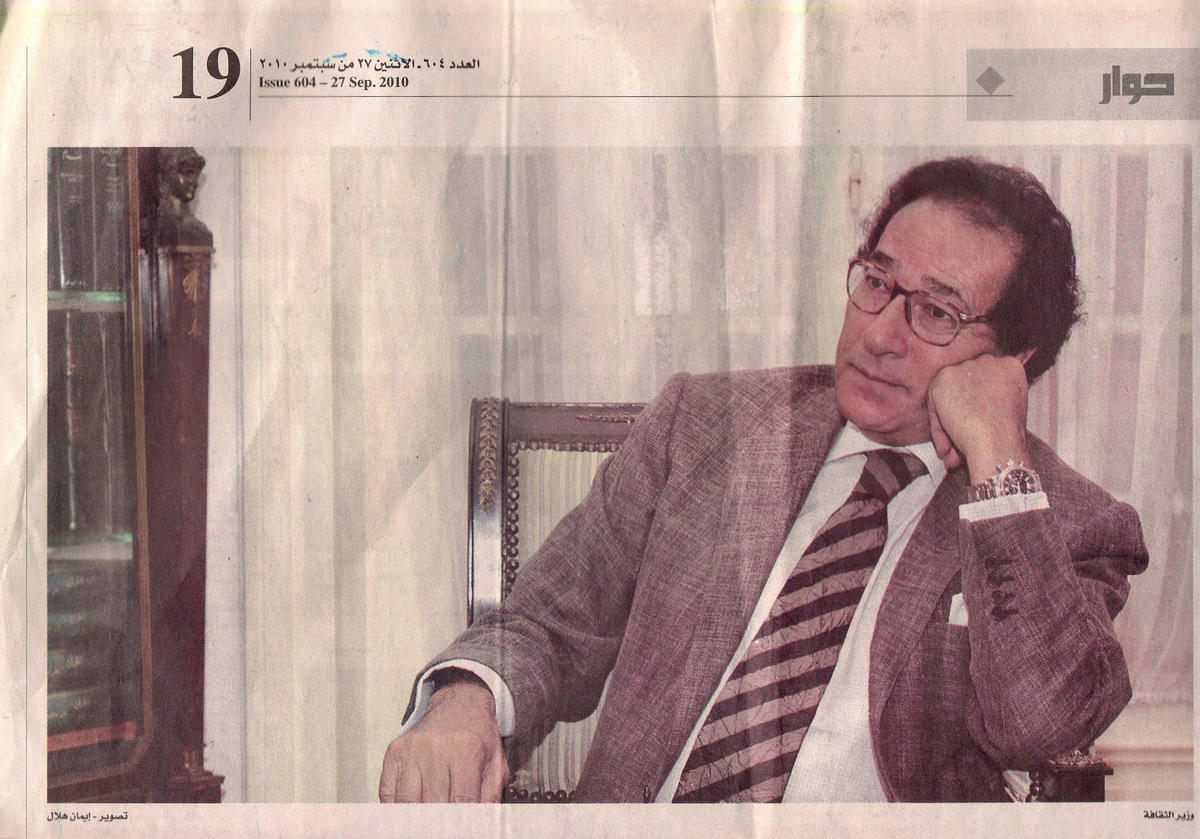

Hosni, a shrewd politician, has remained more aloof than his rival while making himself more available to the media than usual. In a recent interview he mentions the personal suffering he endures as a consequence of his excitable artistic temperament on the one hand, and his total indifference toward retaining his position at the top of the cultural food chain on the other.8 In retrospect, this assertion of his own emotional/“artistic” nature flavors an earlier comment that concern for Egypt’s cultural patrimony had brought him to the brink of exhaustion: “I’m tired and I can’t sleep. I wake up in the middle of the night fearing for the artifacts of Egypt’s museums.”9

Hosni’s professed ambivalence regarding his career as the country’s cultural impresario chimes with the idea that adopting the role of the artist-bureaucrat is ultimately a sacrifice made by the artist on behalf of a larger good. In response to one journalist’s pointed question, Hosni claimed that he has held on to the position of Minister of Culture for twenty-seven years, despite his own dear wishes, at the insistence of the president himself. If this account feels unsatisfying, there are few alternative narratives, despite the perennial question of how to explain Hosni’s mysterious ministerial longevity. As a result fantastical-sounding rumors fill in the gap — like the story that Hosni moonlights as a fashion adviser to the president’s wife, Suzanne, and thus enjoys her protection.

For his part, Shaalan may rightly claim to have taken the special dilemma of the artist-bureaucrat as central to his own artistic project. His body of work prior to the scandal dealt prominently with the theme of the individual enchained by the constraints of bourgeois respectability and office culture. This was done using the most unoriginal metaphors: office suits inflate to giant proportions, threatening to drown their unhappy wearers; an emasculating striped tie binds and gags a man’s head; an enchained and defeated-looking male is forced to carry the prone body of a nude woman and associated props of domestic life on his head. The works demonstrate a certain point about the artist who is pressed into government service.

In his first interview since his release on bail, pending appeal, Shaalan decried the priorities of a state that would value a minor painting by a major artist above the freedom of one of Egypt’s leading artistic talents: himself.10 Apparently, this high-level cultural official emerged from prison a born-again aesthete, a little thinner and perhaps sounding a trifle unhinged, but in full possession of a voice proper to the artist-bureaucrat. While Hosni admits that the emotional rawness has made it difficult for him to complete any new works during these trying times, the scandal has proven to be a creative boon for Shaalan. He describes the period of incarceration as allowing for a return to his true vocation, and claims to have produced fifty new works — almost one work a day. These appear to be (true to his style) highly symbolic, autobiographical, and painfully easy to decipher. The interview prominently features a photograph of Shaalan holding up to the camera what is apparently an ink drawing of a figure lodged halfway inside a narrow manhole. A prison cell door stands ajar in the background. Predatory-looking black cats swarm around the figure, while a particularly large, fanged, and anthropomorphic feline beast seems about to bite at his face. (The latter is a new recurring symbol of Shaalan’s: “No, not [symbolizing] anyone in particular,” he claims in response to the journalist’s question.)

The generative potential of the fall-out of the theft first came to light with the emergence of a humble sketch, a collaborative effort, in fact, between Shaalan and former museum guard Alaa’ Mansour, who shared his cell, both awaiting trial at the time. The drawing is said to portray a suspicious youth that Mansour reported seeing on the day the painting disappeared: a young man “of medium height… green eyes and light-colored hair.”11 The result is a bit stiff and idealized, more like an awkward teenage doodle than a composite sketch. While this new development in the case failed to impress the criminal investigators it must surely have reawakened in the public consciousness the issue of Shaalan’s true vocation as artist. That the young man may never have existed seems beside the point, really. What is more important is that somewhere, out there, is another man possessing the nebulous, yet potentially awesome creative powers of the artist wedded to the respect due a high-ranking government official.

The interview puts on full display Shaalan’s recently heightened persona as an “artist first, bureaucrat, second,” as well as the centrality of his underdog-role in relation to Hosni and his claims to represent a down-to-earth man of the people. Each contention informs the others, and the approach turns Hosni’s position of power to Shaalan’s advantage. If the beardless Hosni sails to work on a yacht maliciously stroking his new silk cravat, Shaalan’s experience of jail is deeply spiritual, allowing him to reconnect simultaneously with his work as an artist and with the commoners populating the country’s prisons — Cairo’s own imprisoned “awlad al balad.”

Herein is a two-pronged approach by which Shaalan alternately frames Hosni as the bureaucrat of popular imagination — shrewd, inauthentic, and corrupt even in his dealings as an artist12 — and defines himself in contrasting terms. Thus Shaalan welcomes material hardship and scorns authority, whether in the person of Farouk Hosni, embodying governmental power, or the Mona Lisa, embodying the western artistic canon. “The Mona Lisa is no Haifa Wehbe” he remarked dismissively, comparing the half-smiling lady unfavorably to a famously hypersexualized Lebanese pop star by way of asserting his own claim to make distinctions, at any register, regarding the relative worth of works of art and, potentially, issues of worth in general.13

Both Shaalan and, of course, Hosni have benefited tremendously from the Ministry of Culture’s de facto policy of recruiting artists to head arts institutions. The long-standing application of this approach has yielded a number of predictable results in the context of a cultural sphere largely reliant on support from the government and the network of employment opportunities it makes available to graduates of the country’s various fine arts and arts-education departments. In a perpetually self-renewing cycle, a fiercely guarded cliquishness informs which artists receive attractive positions in the government and which artists receive attention for their work. Often they are the same. The person, the bureaucrat, and the artist are encouraged, in this situation, to merge without ever becoming fully reconciled. And the source of the individual’s often very real authority within this context is nonetheless commonly acknowledged to have been unmoored from any merit-based system. Authority is instead continuously displaced from artistic prowess to administrative rank and back again; if it resides anywhere in this system it is in its performance by the individual. In this context, the often debatable question of artistic value is regularly “decided” by men in suits behind desks, a prerogative and demonstration of their authority to do so, and as such, must be continually restated, sometimes leading to surprisingly idiosyncratic pronouncements. The tensions and anxieties latent in the hyphenated figure of the artist-bureaucrat help determine the language of these utterances and lend their claims to authority a certain resonance.

It seems disingenuous, therefore, to claim that the prolonged bickering of these two figures is interesting primarily for the light it sheds on the question of who’s to blame, and even less for what it reveals about the country’s cultural infrastructure: A general state of decay has been in effect for as long as anyone can remember, part and parcel of a decades-long process of public sector atrophy. And while the sentencing of Shaalan and ten staff members of the Mahmoud Khalil Museum seems patently unfair, pushing the question of responsibility quickly threatens to spill over into an indictment of the entire system, an exercise that is certainly off the table as an issue of public debate.

Reading between the greasy lines of newspaper print one might, instead, understand Shaalan and Hosni’s public statements as different takes on the same argument. At first glance, this would seem to concern the claims of each to embody the ideal of the “artist-bureaucrat.” Shaalan and Hosni offer competing prototypes in this regard. At the same time, the critical role of the artist-bureaucrat is never questioned. Implicit in their competing claims is an anxiety concerning the continued relevance of the model of governmental cultural policy now in place — a model deeply invested in the practice of hiring artists as cultural administrators, yet obviously implicated in the most recent failure to protect a piece of national heritage. In this sense, traces of the “bigger picture” and the lingering implications of assigning responsibility for systemic failure remain in the press coverage of the scandal, though they are securely couched in terms of the personal feud between the two men.

1. This translation takes into account the associated expressive connotations of Shaalan’s assertion in Arabic: “zaharat al‘kheshkhash’ loha ziballa.” Thus, while understood in everyday language to denote “garbage,” the word “ziballa” is translated here as “piece of shit.” Mohsen Shaalan, interview by Fatima al-Dakhakhani, Al Masry Al Youn (October 17, 2010):17.

2. Ibid.

3. An article on the theft for Al Ahram Weekly attributes these accusations to Ashraf El-Ashmawi, the Minister of Culture’s legal consultant. Nevine El-Aref, “Out of Frame,” Al Ahram Weekly (August 26–September 1, 2010): 1. Criminal investigators confirmed the details in a report recounted in newspapers on August 30.

4. Ehab Al Zalaqi, “Ayna thahabet lohat ‘Zaharat al-Kheshkhash,’” Al Masry Al Youn (September 9, 2010):12.

5. “Moshen Shaalan: Farouk Hosni yedir al-wizara bi-miyoulihi al-shakhsiya,” Al Shourouq (August 29, 2010):1.

6. A letter from Shaalan to the attorney general making these accusations against Hosni was quoted in various newspapers. See, for example, articles published on the front pages of Al Masry Al Youn and Al Dostour on August 27, 2010.

7. “Mohsen Shaalan: Farouk Hosni yedir al-wizara bi-miyoulihi al-shakhsiya,” Al Shourouq (August 29, 2010):1.

8. Farouk Hosni, interview by Amr Khafagi and Samir Al Gamal, “Atamana al-baqaa’ filwizara hata ‘am 2012,” Al Sharouq (September 27, 2010): 19.

9. Nevine El-Aref, “Out of the Frame,” Al Aroun Weekly (August 26–September 1, 2010):1.

10. The source for all references in this paragraph is Mohsen Shaalan, interview by Fatima al-Dakhakhani, Al Masry Al Youn (October 17, 2010):17.

11.Nevine El-Aref, “Tit for Tat,” Al Ahram Weekly (September 2–8, 2010):3.

12. “Moshen Shaalan: Farouk Hosni yedir al-wizara bi-miyoulihi al-shakhsiya,” Al Shourouq (August 29, 2010):1.

13. Mohsen Shaalan, interview by Fatima al-Dakhakhani, Al Masry Al Youn (October 17, 2010):17.