London

Recognise

Contemporary Art Platform

June 22–September 7, 2007

Predrag Pajdic is rapidly becoming something of a Hans Ulrich Obrist of Middle Eastern art. In the past two years, he’s curated three sprawling shows in the United Kingdom, dedicated to work of and about the Middle East region. These shows have unabashedly recycled artists and been accompanied by a veritable maelstrom of information, from interminable websites to catalogues, interviews, and so on.

It’s difficult to decide whether Pajdic’s efforts are totally admirable, or whether they unforgivably perpetuate a number of problems involving the way in which Middle Eastern art is generally presented in the United Kingdom. His stated intention to provide a platform for Middle Eastern artists and others who defy stereotypes in their representation of the region is certainly worthwhile. ME artists are underrepresented on our self-absorbed island, and on the rare occasions when they have been represented, they’ve more often than not been fetishized and politicized beyond the possibility of being taken seriously as anything other than Others. But the tide is now gradually turning, as demonstrated by exhibitions at Modern Art Oxford and Tate, and Pajdic has played a role in raising the profiles of artists from the Middle East.

At the same time, this curator, who hails from the former Yugoslavia, seems to have a problem with the essential process of curating a show: that is, selecting it, editing it, and bringing it together in some sort of coherent, logical fashion while at the same time giving each work sufficient breathing space, allowing it to maintain its aesthetic and political integrity, distinct from the group. Much of what was on view in ‘Recognise’ was substandard. Nada Prlja’s 2007 posters, which read “Bin Laden is Dead,” seemed to do little more than replicate the classier variety of graffiti circa 2001; while Sagi Groner’s Jenin Journal (2005), an account of watching the Israel Defense Forces’ destruction of the Jenin camp from Amsterdam, had potential for interest but was underdeveloped. (The finer aspects of the documentary trend in Middle Eastern art have been debated previously and were thoroughly presented in Modern Art Oxford’s 2006 compendium ‘Out of Beirut’—one longed here for a bit more of the thought that went into that exhibition.) Some of the work was just plain old, such as Wael Shawky’s The Cave, admittedly brilliant but on rotation at every gallery near you since 2005.

The sheer quantity of mediocre offerings was a pity (the ‘Recognise’ press release trumpeted more than forty artists; other sources put the number at sixty-six), tending to drown out, in some cases literally, works of greater quality. The sound on Lisa K Blatt’s video Marco Polo (2003), a three-minute loop of some old-age pensioners playing Marco Polo in a swimming pool in the nether regions of the United States, with the words “Osama Bin Laden” substituted for the standard call and response, was turned too high. Mildly amusing as it was the first time around (in a YouTube sort of way), the OAP’s shouts didn’t take long to grate and seemed to provide a metaphor for the bombardment that spoiled the show.

To avoid giving a wholly negative impression of the gathered works, a few that stood out should be mentioned. Ayman Ramadan’s excellent Iftar (2006) presented a staged set of men breaking their Ramadan fast on a street in downtown Cairo, with food supplied by the street’s mechanic. Standing at the table in the dark, dressed in dusty clothes, eating and talking, they strangely resembled the disciples of The Last Supper—an implication made consciously on Ramadan’s part, yet one that he didn’t overplay; the men still retained an identity beyond the allusion.

On the floor in the second room, Tarek Al-Ghoussein displayed images from his Self-Portrait series. In these photographs he wore a keffiyeh, with his face hidden from view, and stood against various backdrops: an airplane on a tarmac; a docked, rusted ship; a lake—all strangely neutral in their colors and locations. The images’ impressively clean composition and production made up for any lapse in subtlety caused by the purportedly incongruous juxtaposition of “Arab” and “neutrality.” Yasmeen Alawadi’s photographs of construction work in Dubai (from Grid Work Series, Dubai, 2007) were also well composed and presented, hung from a scaffold at the exhibition’s entry. In one, a single red work glove was placed on a railing against a steel grid; in another, a blue-suited construction worker with a white scarf wrapped around his head and mouth walked by a sea of grids. The point wasn’t labored, but the images brought to mind the shocking conditions for workers in the booming city.

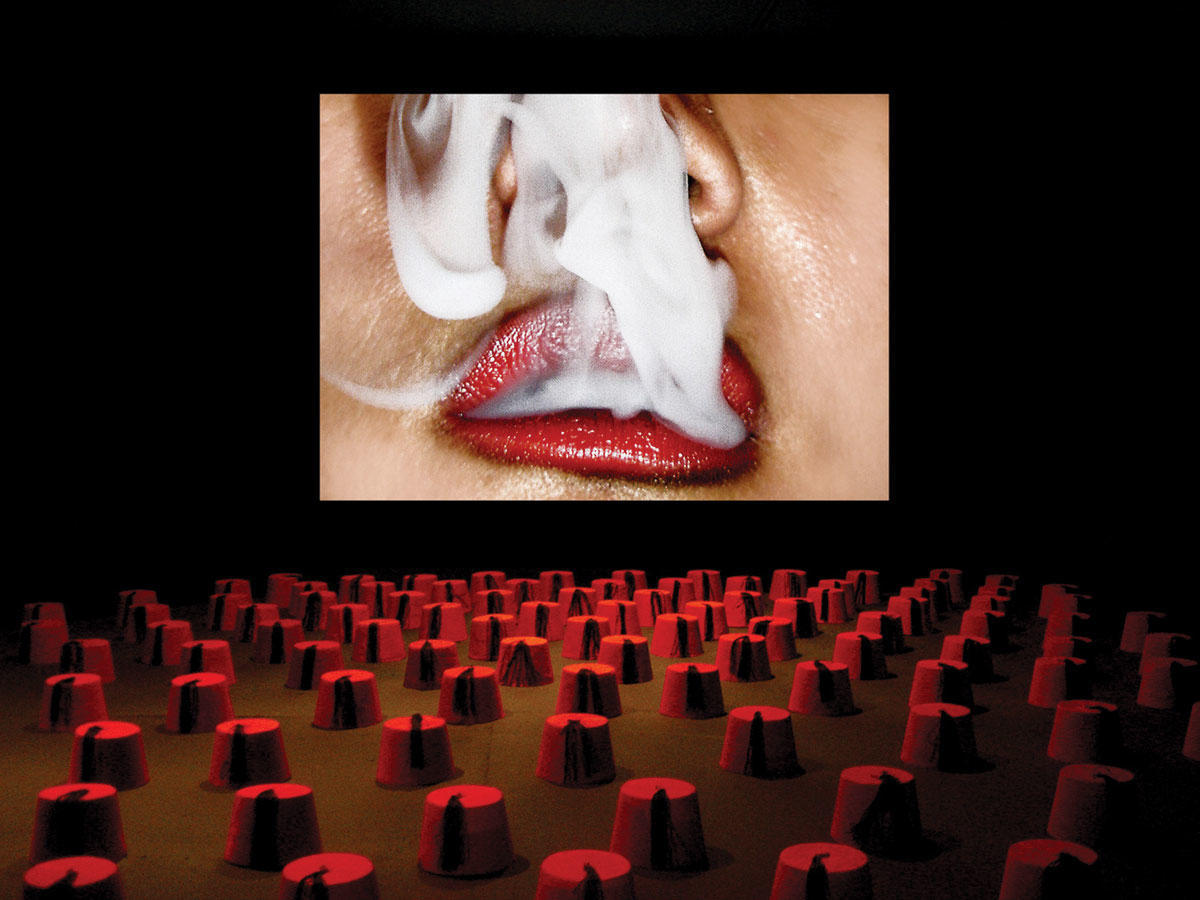

The exhibition also presented an old hit by Emily Jacir (her 2003 circular baggage carousel embrace) and Mahmoud Hojeij’s disturbing video Shameless transmission of desired transformations per day (2002), in which single Beiruti women recount their sexual encounters under harsh spotlights, segments intercut with the sexist ramblings of a greengrocer.

So it wasn’t all bad, and Pajdic does deserve special commendation for his indefatigability and his presumably bulging Rolodex. But perhaps now that the groundwork for Middle Eastern art has been indisputably laid, future exhibitions can move on from such indiscriminate barrages of art from an underrepresented region and start being a little more discerning in their selections.