My cousin Samir ushers me into his apartment overlooking Beirut’s waterfront. Contemporary art hangs on the walls, and the only view from the windows is the steely blue of the Mediterranean. The walls are freshly painted — an annual ritual, a precaution against the sea air. But this year they are no longer their customary eggshell hue. The large living room has been painted hunter green, the bedroom walls are tangerine, and the sitting room is a pale yellow: the three colors of Lebanon’s opposition alliance.

A bookcase lines one wall of Samir’s sitting room, full of texts on politics, history, and finance, in English and Arabic. Samir, a well-to-do businessman from a Maronite Christian family, directs my attention to one shelf in particular, a shrine to his heroes. There is a box set of songs by Fairouz, the legendary singer whose music is the elemental stratum of Lebanese nationalism. There are the complete works of Khalil Gibran, the Lebanese-American author of mystical works like The Prophet, Nymphs of the Valley, and Jesus, the Son of Man. And there is a collection of the speeches of Sayyid Hasan Nasrallah, the charismatic Shia cleric and leader of Hizbullah, including his famous underground communiqués from last July, during the Israeli invasion. After the war, with much of Lebanon’s infrastructure shattered, entire city blocks demolished by Israeli bombs, and an oil slick inching up the coast, Nasrallah declared victory. At least half of the Lebanese, millions of Arabs, and many Israelis agreed with him.

“Fairouz, Gibran, Sayyid Hasan,” Samir says, beaming. An unlikely trinity, perhaps. But in today’s Lebanon, where political alliances spring up between once-bitter enemies and the lines of confessionalism are increasingly blurred, the unlikely has a way of seeming inevitable. Since the assassination of Prime Minister Rafiq al-Hariri in February 2005, the Lebanese have been fighting their way through a series of crises and opportunities, from the explosive but short-lived “cedar revolution” to the departure of the Syrian Army to the Israeli invasion, all heading into this year’s presidential elections.

Take, for instance, Julia Boutros. A middle-aged, French-educated Orthodox Christian and singer of such mild nationalistic tracks as Ghabat Shams al-Haq (The Sun of Truth Has Set) and Wayn al-Malayin (Where Are the Millions?), Boutros was catapulted to the front rank of contemporary Arab pop for her song Ahibba’i (My Loved Ones). Released less than a month after the UN-brokered ceasefire that ended the July War, the song’s lyrics were adapted from a letter by Nasrallah to his troops, composed in a secret bunker at the height of the bombing campaign. Within days of its release, the five-minute, twelve-second tribute to the fighters of Hizbullah was blaring continuously from loudspeakers all over Beirut and on radio stations across the region. One month after the release of the single, the video for Ahibba’i arrived, with a campaign to raise funds for the families of those who had perished during the war. The sales of the CD and accompanying DVD far exceeded Boutros’s million-dollar goal, fueling a debate between those who see Hizbullah as national heroes and those who regard the group as a scourge.

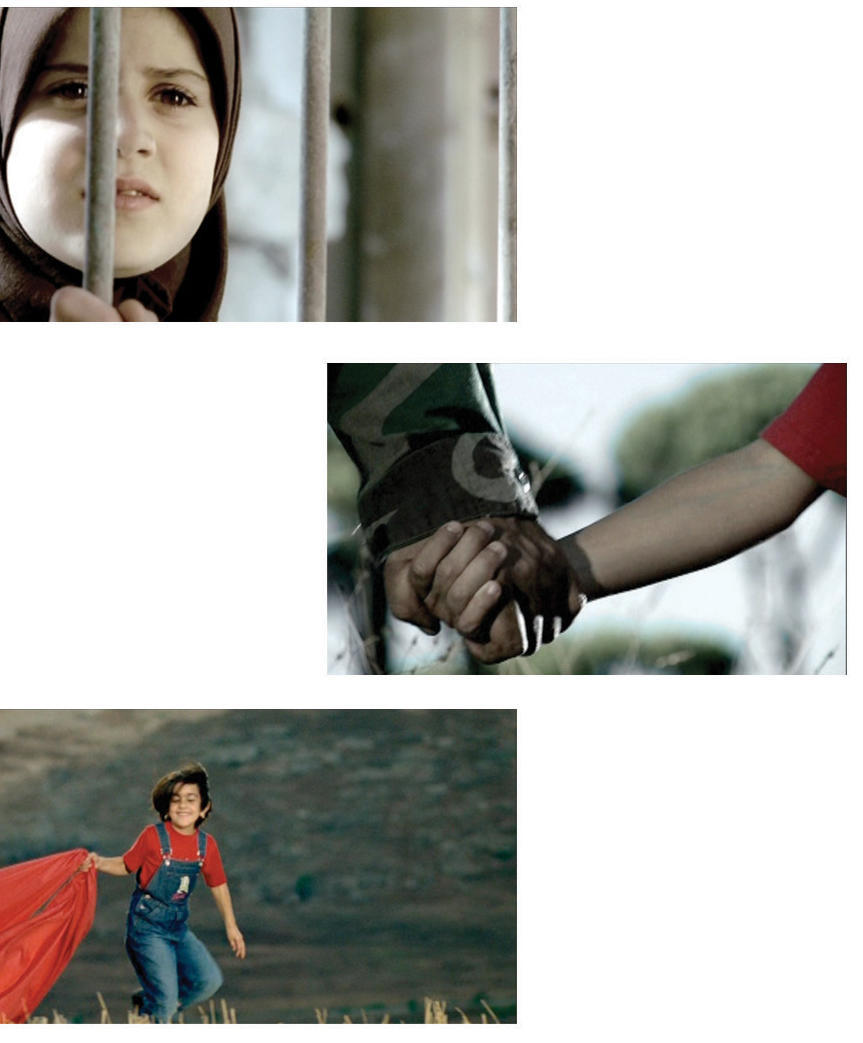

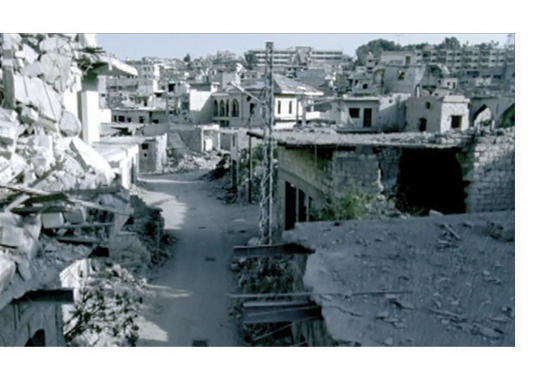

The video opens on scenes from al-Dahiya, the southern suburb of Beirut. Dust hangs in the air and apartment buildings lie toppled on one another, reduced to rubble by Israeli jets. Faces peer out of ruined houses as a woman walks by. She cuts a striking figure, clad in a black abaya, her chestnut hair spilling luxuriantly over her shoulders. As she strides solemnly through the alleys, children dart out of their houses to follow her, morphing briefly into camouflaged warriors bearing assault rifles. Soon a crowd of boys and girls surrounds her as she intones:

Through you shall the captives be freed

Through you shall the land be liberated

The emotional climax of the song arrives as we cut to scenes of handsome commandos moving stealthily through Lebanon’s woodlands, silhouetted against umbrella pines:

You are the glory of our nation, you are our leaders

You are the crown on our heads and you are the masters

The last word of this verse is saada, the plural for sayyid, which means “master” or “lord” but is also the title given to those believed to be the descendants of the prophet Mohammed, like Nasrallah himself. This piece of rhetorical brilliance is typical of Sayyid Hasan: in addressing his soldiers — most of whom come from the poorest classes in Lebanon — as the nation’s saada, he inverts the social hierarchy, emptying hereditary titles of their conventional meanings.

Even among Hizbullah’s opponents, the mesmerizing quality of Nasrallah’s political persona is undeniable; to his followers, he is already larger than life. After the war, his popularity in the Muslim world reached heights unattained since Gamal Abdel Nasser. His gentle voice, beatific smile, and twinkling eyes command the attention of a nation of political junkies. His speeches and interviews are delivered in a mix of flawless classical Arabic and colloquial Lebanese. He is a master at manipulating linguistic registers, now issuing an ultimatum with the sharp inflections of a pulpit preacher, now disarming his audience with a coy joke in the Beiruti vernacular. His voice is rendered even more distinct by a speech impediment, which is imitated by many of his younger followers with a near paraphiliac fixation. The details of his personal life — some true, others urban legends — circulate among Lebanon’s bourgeoisie like so much salacious mythography.

At the beginning of the war, a woman wrote to him asking that he send her the abaya he wore while in hiding. Soon enough, the gossip mill had transformed this anonymous woman into Haifa Wehbe, the gorgeous Lebanese starlet famed for such exuberantly cheesecake songs and videos as Ana Haifa (I Am Haifa) and Bus al-wawa (Kiss My Boo-Boo). In one version of this story, circulated as fact, after Haifa asked Nasrallah for his abaya, the two secretly married. It is this dynamic of jarring transgression between a booby Western-style pop star and the austere leader of an Islamic militant group that undergirds, in a more subtle fashion, the visual language of Julia Boutros’s famous music video.

Critics and commentators tended to focus their attention (or ire) on the video’s provocative pairing of child and soldier. But the most interesting thing about the song, and the source of its resonance with popular sympathies, is Julia’s performance of Nasrallah. By transposing his words to music, dressing like him, walking in his environment, and addressing his “loved ones,” Boutros translates his persona into an altogether different, yet ideal, form. In Julia’s impersonation, a kind of perfection is achieved: Nasrallah’s mellif luous and sonorant cadences become music, and he is transformed into a beautiful woman, serenading the beloved who listens, hypnotized. Thus does the unmistakable voice of the poor grocer’s son–turned–militia leader shed its signature blemish and provincial inflection, acquiring an expansive nationalist tenor in the mouth of a Christian woman.

Recently, embattled pro-Western prime minister Fouad Siniora grumbled that all Hizbullah needs is “a composer for a national anthem of their own.” One wonders if he owns a radio.