In September 1974, the Mandala Collaborative received a letter of intent from the Iranian minister of culture and arts to design a new home for the Tehran Symphony Orchestra. It was a prestigious undertaking for the young Iranian firm, a landmark project that excited the interest of the Shah himself. As in so many fields of endeavor, the ambition was to make a great leap forward, from backwardness to the cutting-edge. If the city’s several musical groups were ill-served by the small, overbooked, and understaffed Roudaki Hall, they would soon have one of the largest auditoriums in the world, with seating for 2,000 concertgoers and the finest acoustics money could buy.

It was an era of great plans and major projects. Tehran, which had just hosted its first international film festival in 1973, was to acquire a new museum of contemporary art next to Farah Park. A forward-looking “city of the arts” was planned for Shiraz, a research and performance institute to encompass sound, painting, sculpture, cinema, theater, ballet, poetry, and literature. As with Mandala’s Center for the Performance of Music, these various projects were meant to benefit Iranian audiences while impressing upon others the world-class status of a nation that styled itself “the most crisscrossed crossroads in the world” and the inheritor of thousands-year-old traditions.

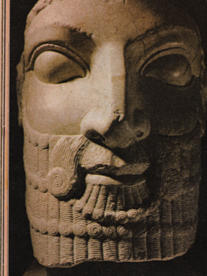

The design concept for the symphony hall was based, Mandala claimed, on the “unifying organizational conceptions of Persian ‘place making,’” especially the garden, both the “hidden garden” — an open courtyard surrounded by indoor spaces — and the “manifest garden” surrounding the indoor spaces. The idea was to create a “concentric series of spaces” that would rhyme with and be expressed by the design’s centerpiece, a twelve-meter-tall ziggurat sloping up to the sky in rounded, circular steps. The whorled ceiling of the auditorium was at once functional — minutely calibrated to achieve optimal reverberation — and symbolic, evoking the graded textures of the walls at Persepolis, the ruined capital of the Achaemenid Empire just outside present-day Shiraz. Extensive rectangular gardens were meant to recall pardises — the ancient Persian ornamental gardens from which the English word “paradise” derives. The ceremonial staircases at Persepolis were reproduced, while the raised platform in the main hall echoed the Apadana, Darius’s audience hall.

The project, which also involved the American firm of Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill, proceeded slowly. Thousands of drawings and plans were devised; a model was produced and personally inspected by the Shah. It was very much a royal symphony hall, tailored to the needs of the emperor, with separate entrances for the conductor, the service workers, and the royals. The main entrance for commoners faced Pahlavi Avenue, near a proposed stop for the then-unbuilt subway. By 1978, as the Shah’s repressive apparatus lost control of the country and Iran pitched into its revolutionary moment, the principals of the Mandala Collaborative fled the country. Yahya Fiuzi, the partner in charge of the design, had quit both Iran and Mandala the previous year; Nader Ardalan, Mandala’s founder, attempted to keep the project going from his new home in Boston. But as the clerical regime consolidated power, the idea of a royal symphony hall became an anachronism, yet another reminder of the epic waste and misplaced priorities of the Pahlavi era. Like so many things, it was a step too far, the latest in a long line of glory-mongering excesses.

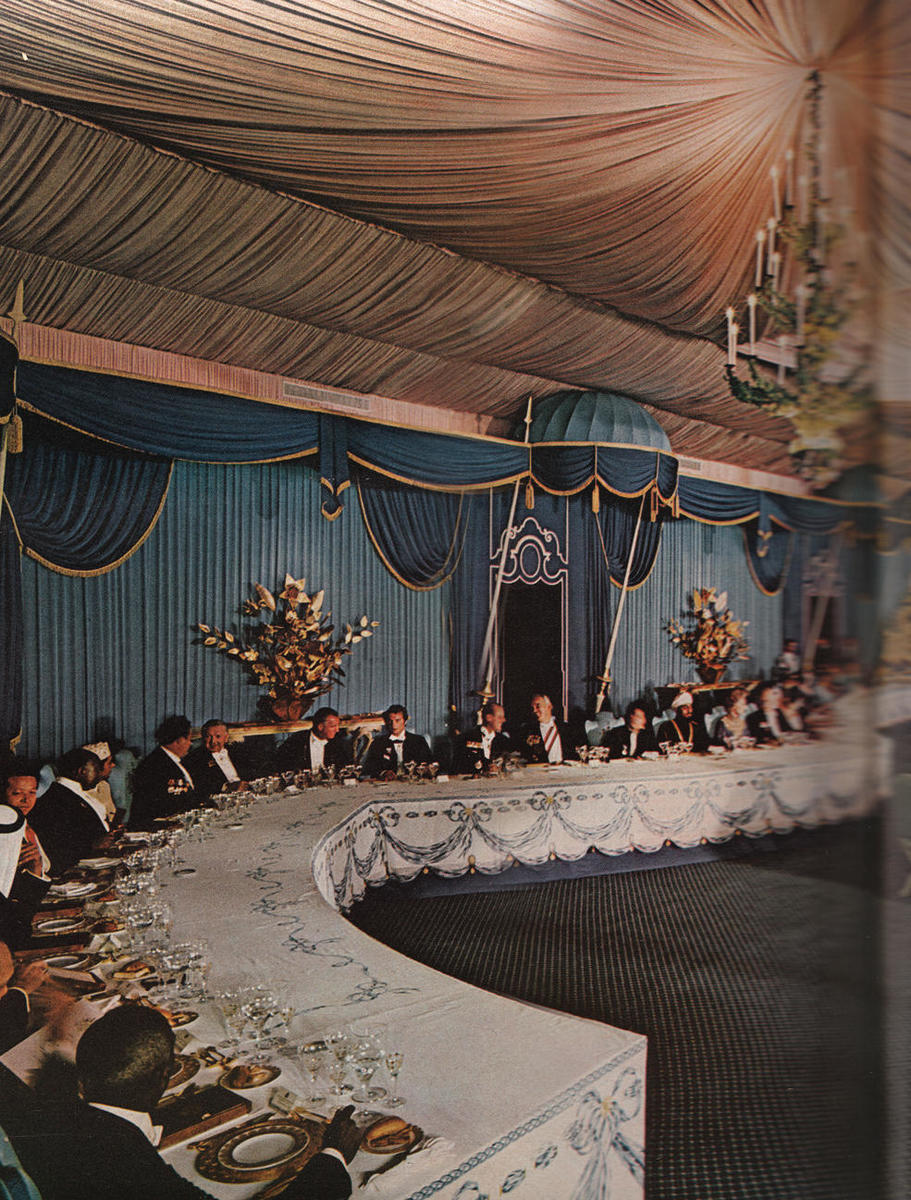

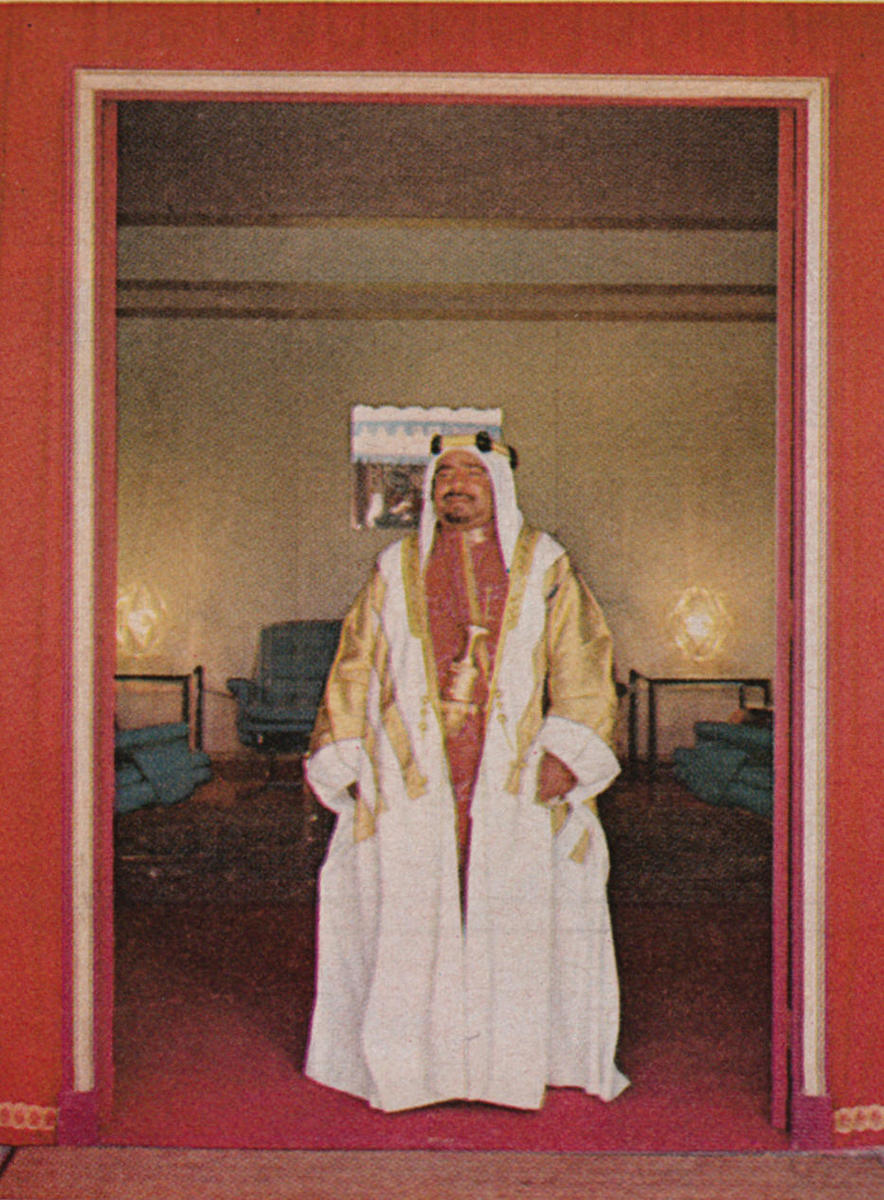

In 1971, Mohammad Reza, Shah of Iran and self-styled “light of the Aryans,” celebrated the 2,500th anniversary of the founding of the first Persian Empire with a party for six-hundred friends and admirers — celebrities, politicians, and potentates from across the globe, including Orson Welles, Prince Juan Carlos of Spain, King Hussein of Jordan, Pat Nixon, and Nicolae Ceausescu. Haile Selassie, the Negus of Ethiopia, had pride of place, as representative of the world’s oldest government. The events began at dawn on October 12, at Pasargad, with an apostrophe to the Shah’s most illustrious forebear. “After the passage of twenty-five centuries, the name of Iran today evokes as much respect throughout the world as it did in thy day,” the Shah said, standing before the tomb of the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. “Cyrus, Great King, King of Kings… . Sleep on in peace forever, for we are awake and we remain to watch over your glorious heritage.”

Xenakis was a frequent guest of the Shah and the Shahbanou, Empress Farah Diba, whose patronage made possible an array of cultural happenings, including the Tehran International Film Festival and the Shiraz Arts Festival. The first Shiraz festival had been held in 1967; over the next decade, the event brought a profusion of the West’s most progressive composers, musicians, visual artists, filmmakers, playwrights, and directors to Iran, along with traditional musicians from the East. Orghast, the first project of Peter Brook’s radical Paris-based International Center for Theatre Creation, premiered at the Shiraz festival in 1972 with a mixed troop of European, Japanese, and Iranian actors and a script (in a made-up language also called Orghast and supplemented with Greek, Latin, and Avesta) by Ted Hughes. Merce Cunningham’s dance company performed there, as did John Cage. Modern and electronic music was particularly favored; Karlheinz Stockhausen received multiple major commissions, while Xenakis, who had presented several ambitious works (including a 1969 choral work dedicated to political prisoners, among them “thousands of forgotten ones whose names are lost”) was asked to be director of the proposed arts center in Shiraz.

Though the audience for the Shiraz festivals was mostly Iranian, the predominance of Western artists and the vast sums spent preparing Shiraz for visitors made them, like the imperial celebrations, a magnet for criticism. Iranian newspapers denounced modernist tendencies (like Stockhausen’s “meaningless” music). Liberal reformers sometimes echoed religious complaints, insisting that the monies spent on these foreign-dominated cultural events might be used to improve the lives of average Iranians. But the cultural dimension was always close to the surface. The 1977 Shiraz Festival featured Pig! Child! Fire!, a play by the radical Hungarian theater troupe Squat that evoked Dostoevsky, Breton, and Artaud while making use of graphic nudity, an animal corpse, and acts of extreme sexualized violence. Squat’s antics had gotten them expelled from various European cities and stripped of their Hungarian nationality; their appearance in Shiraz, in those late days of the empire, felt like the greatest provocation yet. Khomeini again weighed in, this time from Paris: “[I]t is difficult to speak of. Indecent acts have taken place in Shiraz, and it is said that such acts will soon be shown in Tehran too, and nobody says a word.” He needn’t have worried; 1977 was to be the final Shiraz Festival, and Khomeini himself would be returning to Tehran soon enough.

In his first speech to the new nation that he had done so much to will into existence, the Ayatollah Khomeini declared, “We don’t need markers of civilization… . We need markers of Islam.” In the years that followed, a host of new journals attempted to define the aesthetic sensibility of the Islamic Republic. Two of the most influential were Faslnameh Honar (Quarterly Journal of the Arts) and Sureh (Qur’anic Verses). Article after article denounced the art and architecture of the Pahlavi era as either slavishly Western or regressively Persian, or both, while working to recuperate the nation’s Islamic legacy.

Zahra Rahnavard, head of the Al Zahra School of Art, wrote in Faslnameh Honar, “Our Revolution has been a bridge between matter and meaning, between ‘us’ and the ‘divine.’” Revolutionary art, she said, should be ayeh gara (spiritual, Qur’anic, intuitive) rather than vaghe gara (realistic). In this case, her commentary was directed less at the imperialist West than the socialist East — specifically, socialist realism, with its blandly heroicized depictions of individuals making history, which Rahnavard believed was threatening to “dismantle the precious goals of our revolution.”

The idea of the museum itself was also subject to interrogation. An editorial in Faslnameh Honar demanded that, rather than catalogue or represent the arts of past epochs, the revolutionary exhibition would submit the work of art to the judgment of Islam. (Certainly, lovers of modern art feared the summary judgment of the clerics; the basement of the Museum of Contemporary Art became a storehouse for the largest collection of twentieth-century art outside of Europe and North America, including pivotal works by Picasso, Pollock, and Grosz, as well as a silkscreen portrait of Empress Farah by Andy Warhol.) By this light, in fact, the perfect museum was the Qur’an itself, a space in which stories from the past could constantly be reevaluated to provide life lessons for all Muslims throughout time. This indifference or hostility to the non-Islamic past extended across the humanities. One cleric, writing in Faslnameh Honar, lectured that what Iran needed was not a font of superstition like the Shahnameh (“The Book of Kings,” the eleventh–century poem that was the holy writ of Persian nationalism) but a pasdar nameh (a “book of the revolutionary guard”). Archeology suffered, as well. The Institute of Archeology at Tehran University was closed; funding was slashed or eliminated for ongoing work at various locations, including Persepolis.

In June 1997, nearly two decades after his departure, Fiuzi received a phone call at his home in the suburbs of Washington, DC. It was a representative of the Iranian government, calling with a proposition: Could he lead the design and construction of a grand meeting hall, to be completed in time for the Eighth Summit of the Organization of Islamic Conference — just over five months away. In the wake of Mohammad Khatami’s surprise election in May, the OIC summit was to be a watershed in the history of the Islamic Republic. Iran had boycotted the last five OIC summits over the organization’s refusal to condemn Iraq for the Iran-Iraq war, and the December summit was to be a kind of coming-out party. President Khatami would launch his “dialogue of civilizations” initiative at the summit, beginning with the assembled Muslim dignitaries, many of whom represented countries that the Islamic Republic had broken off relations with (including Egypt, which had briefly sheltered the dying Shah two decades earlier, in the first days after the revolution). Fiuzi was tasked to revive Mandala’s design for the Center for the Appreciation of Music. His team proceeded to produce some 4,800 drawings, including designs for fabrics and furniture; many were 1970s plans re-rendered with AutoCAD. The new complex would feature resting halls, prayer halls, and meeting rooms, though the focus remained the circular center, formerly the main concert hall, now a tent-like auditorium in which to install some fifty-odd heads of state and their retinues. The timeline required Fiuzi’s team to carry out the design and the construction virtually simultaneously. Six thousand workers laboring around the clock ensured that the construction of the building was finished on schedule.

The new design had to be modified in form as well as function. In light of the occasion of its construction, the conference center was to represent the achievement of Islam, not the timeless glory of the Persian Empire. Fiuzi would have to gut the Achaemenid elements from the original plans and replace them with new design elements in an appropriately Islamic style.

Of course, the nature of Islamic style is itself an open question. Fiuzi, under fantastical time and budgetary constraints, provided a new theory of the project, replacing the old paradigm of “Persian place-making” with something he called heya’ti, “rushed style,” a kind of temporary architecture inspired by traditional Shia religious ceremonies. Heya’ti was the name of the ephemeral structures erected in conjunction with the annual mourning of the death of Ali during the month of Muharram. This justification seemed awfully subtle to some observers, including one high-ranking government official, who responded to the open, minimalist interior with a request for glazed blue tiles, massive chandeliers, and Qur’anic verse to make the space more recognizably Islamic. The morning after his site visit, buses bearing traditional tile workers showed up at the site to begin their work. Fiuzi managed to placate the leadership by, among other things, adding calligraphic verses about Muslim unity from the Qur’an to panels in the main vestibule, though even then the effect was minor, as the letters are carved out of the white surface of the architraves.

Neither the building nor the Islamic Summit Conference was a phenomenal success. The conference center received little attention in the foreign press, and it was heralded in Iranian media more for the “rushed style” of its construction than for its design. This was a monumental work built in record speed for comparatively little money, ninety-three percent of it from local sources (and hence only seven percent foreign — the press loved to quote the exact figure). The “dialogue of civilizations,” though adopted by the United Nations as a theme for the year 2001, did not lead to an epic realignment of thought or politics (or even normalized relations with the US). Yahya Fiuzi did go on to get other, more leisurely commissions in Iran, including work on the Tehran International Trade Center and a proposed Farabi Performing Arts and Cultural Center. Today he lives and works in Tehran.

In The Concealment of Beauty and the Beauty of Concealment, a widely distributed pamphlet based on a 1986 address to the Seminar for Studying Hejab, Zahra Rahnavard, head of Tehran’s Al Zahra School of Art, insisted that a woman could only discover her true nature by covering herself:

The body, which is destined to decay, to be mingled with the dust and produce (and be eaten by) worms, even at the pinnacle of its beauty is but an obstruction in the way to real beauty. The beauty of concealment, therefore, lies in the elimination of the physical values in order to revive the values of the real self of a woman in the mind of the society of man and woman.

This celebration of the hidden self and its attendant derogation of the physical was consonant with the general post-revolutionary disinterest in “civilization” and externalized signs of greatness.

But the concern for appearances is an old theme in Iran, an element of the Iranian personality emblematized by aberoo, “the glow of the face.” It is not simply an elite concern; even the poorest households maintain a room for visitors, a kind of sitting room, in which one’s prize possessions are on display for the enjoyment of the guests. Aberoo is the basis of hospitality, even generosity, but it also contains an element of falseness. Those who labor to keep up appearances often have something to hide.

The 2,500th anniversary events were a kind of aberoo, a presentation of Iran’s best face for the consumption of guests, in this case the hundreds of foreigners who descended on the country to participate in or document the celebration. In addition to the tent city and the outlandish meal and extravagant spectacle at Persepolis, the whole city of Shiraz (where journalists and lesser dignitaries stayed) was cleaned up: the prison painted, potted flowers lined along the main roads, caged songbirds hung on lampposts. Shopkeepers were issued handsome blue jackets. After the events were over and the guests had left, the city was stripped of all these ornaments.

The Islamic Summit Conference and its specially commissioned building was a different kind of project, a demonstration of piety and simplicity, the opposite of ostentatious. But it was a kind of aberoo, too. The building was meant for show. It represented an Iranian claim to a different notion of belonging — to the ummah rather than the mellat. As conceived by the regime, it was to be an emblem of the Islamic Republic rejoining the community of Muslim nations, the site for a dialogue of civilizations — which is also, perhaps, to say, the site for a conjugation of glories. For that is the secret of aberoo, and also of glory: It only exists to be talked about.