Tahmineh Milani’s Atash bas (Cease Fire, 2006) recently became the highest grossing film in the history of Iranian cinema. It tells the story of a young couple who, two years after tying the knot, hit a decidedly rocky patch. Eventually, they seek help from a psychiatrist (played by Atila Pesiani), who duly tells them that the key is to “trust the child within.“ (Italian author Lucia Capacchione’s widely read self-help manual Recovery of Your Inner Child is credited onscreen as an inspiration.) Milani cast hot stars Mahnaz Afshar and Mohammad Reza Golzar as Sayeh and Yousef, the warring couple.

Milani, arguably Iran’s most successful female director, built her reputation as a diehard feminist through the polemical films — and international festival favorites — Do zan (Two Women, 1999), Vakonesh panjom (The Fifth Reaction, 2003), and Nimeh-ye penhan (The Hidden Half, 2001), which was deemed counterrevolutionary by the Islamic Revolutionary Court. In Atash bas, however, she appears to reduce the methods and reasoning of the women’s liberation movement to cheap trickery and formulaic spats. The matter of who does the housework is a recurrent issue. Yousef’s mother, dissatisfied in her own marriage, sides with her daughter-in-law, causing Yousef to warn Sayeh, "Didn’t I tell you my mom is a feminist?” Rather than portraying the complexity of gender relations in today’s Iran, Atash bas characterizes the couple’s problems as a Tom and Jerry scenario.

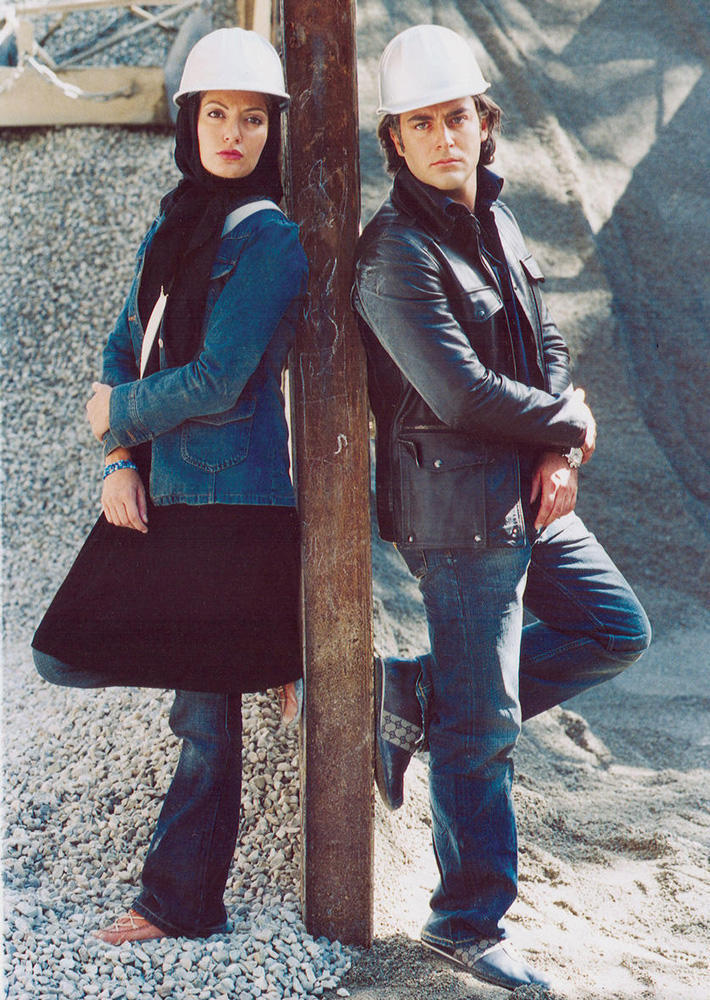

A comparison between the posters for Atash bas and the 2005 Hollywood “Brangelina” vehicle Mr & Mrs Smith reveals another influence on Milani’s writing and direction, and also perhaps her ambition for the film to have the impact in Iran that blockbusters do elsewhere. But given our technical and thematic limitations, Iranian cinema cannot do what Hollywood does: while the ideas and themes can travel, the outcome is but a pale imitation. In the Atash bas poster, the couple lean with their backs to each other, but against a pole, so as to avoid offending the censors. She has to wear her hejab, of course, and the viewer is left to imagine a garter and sexy pistol.

After the screening of her film in Cologne, Germany, Milani proffered some remarks about “the youth of today,” stating, for example, that “the new generation of girls have turned brazen, bad, and wild.” Atash bas was particularly popular with girls in Tehran, offering as it does myriad ideas for how best to taunt the opposite sex. For the characters in Atash bas, the adjectives that Milani uses to describe young women today would be relatively respectful but still, it’s difficult to excuse such insults — especially as it’s these same young Iranian women who helped take the film to the number-one spot at the box office.

The director also seems to harbor some ill feelings towards the urban middle class. She has Sayeh say about another character in the film, “I am sorry to say that this friend of yours is so mediocre.” Milani herself was raised in an urban middle-class family. At some point in her life, she joined a political organization that recruited its members from the youth of this social stratum. Nimeh-ye penhan (The Hidden Half) was a tribute to that era of political idealism. Why should she then belittle the middle classes to such a degree today?

Atash bas’s set designer filled the couple’s house with furniture from IKEA, that universally middle-class brand, which in Iran has found a market among the aristocracy. To indicate the excesses of the upper classes, Milani has her protagonists smash things from IKEA with reckless abandon. In Tehran there seems to be a proportional relationship between the number of people who fall below the poverty line and the proliferation of billboards that advertise luxury items. One current billboard reads: You Can Also Join the Big Family of BMW. It is perhaps beside the point that a Beemer is 20 to 30 times more expensive than the average car. Atash bas opens with a huge BMW sign, Yousef’s personal spacecraft of choice. From the very first shot, the film discloses its affinity to the sick capitalism of contemporary Iran.

Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s 1989 film Arusi-ye khuban (Marriage of the Blessed) opened with the camera looking at the world through the star of a Mercedes Benz. At the time, many critics saw this shot as an example of the director’s backward approach, his confusion of poverty with virtue. Twenty years later, Makhmalbaf no longer lives in Iran, the 1970 German car has been replaced with a 2005 version, and if his film said something about the revolutionary spirit of the time, Cease Fire says something about the preoccupations of a newly formed upper class whose hearts are void of anything to fight and live for.

The twisted attitude of state policy towards sexuality in post-revolutionary Iran, which today must answer to the needs of a disproportionately large youth population, has led to many social ills. Atash bas paints an allegorical picture of these ills: it’s the story of people who have nothing to live for except (the pursuit of) money. They are incapable of establishing the simplest forms of human contact; instead of love or attraction, they communicate through base pranks and buffoonery.

How can the “child within” find the strength to “recover” in this fetid air?