Amsterdam

Objects in Conflict, Israeli and Palestinian Stories

Arti et Amicitiae

May 18–June 4, 2006

In times of conflict and war, the dominant media discourse shifts all too easily into recounting death tolls, numbers of wounded refugees, and costs in material damage. What is often forgotten, or processed for the sake of “breaking news” into consumable bits,a re the personal stories of those who suffer at the hands of violence. If armed conflict is always dehumanizing in every respect, then its by product is that individual subjects — men, women, and children — are reduced to two dimensions, caught up within the larger machinery of militarism and politics.

We tend to invest the objects that surround us with meanings and narratives; a familiar, if not tired, artistic strategy is that of excavating those meanings. Safeguarding the integrity of the object calls for sensitivity in matters of mediation and (re)presentation. The latter becomes most urgent when an artist or curator tries to take up a political point, or at an extreme, when a political agenda seems the most prominent feature of a project.

Such is the case for “Objects in Conflict, Israeli and Palestinian Stories,” an exhibition conceived of by Dutch journalist and art historian Nadette de Visser. Held at Arti et Amicitiae, a white cube space in Amsterdam, the exhibition’s stated aim was to “place the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in a personal context” through the showcasing of sixteen objects, all beautifully photographed and accompanied by the accounts of their owners, half of them Israeli, half of them Palestinian. Exhibitions such as these always walk a fine line between political activism and aesthetics; finding a way for the two to reinforce each other, rather than cancel each other out, is a difficult task. Yet if the objective was to highlight “the conflict seen through the eyes of individual people with their individual story,” then the format of presentation, choice of venue, and omnipotent signature of the curator all worked against it.

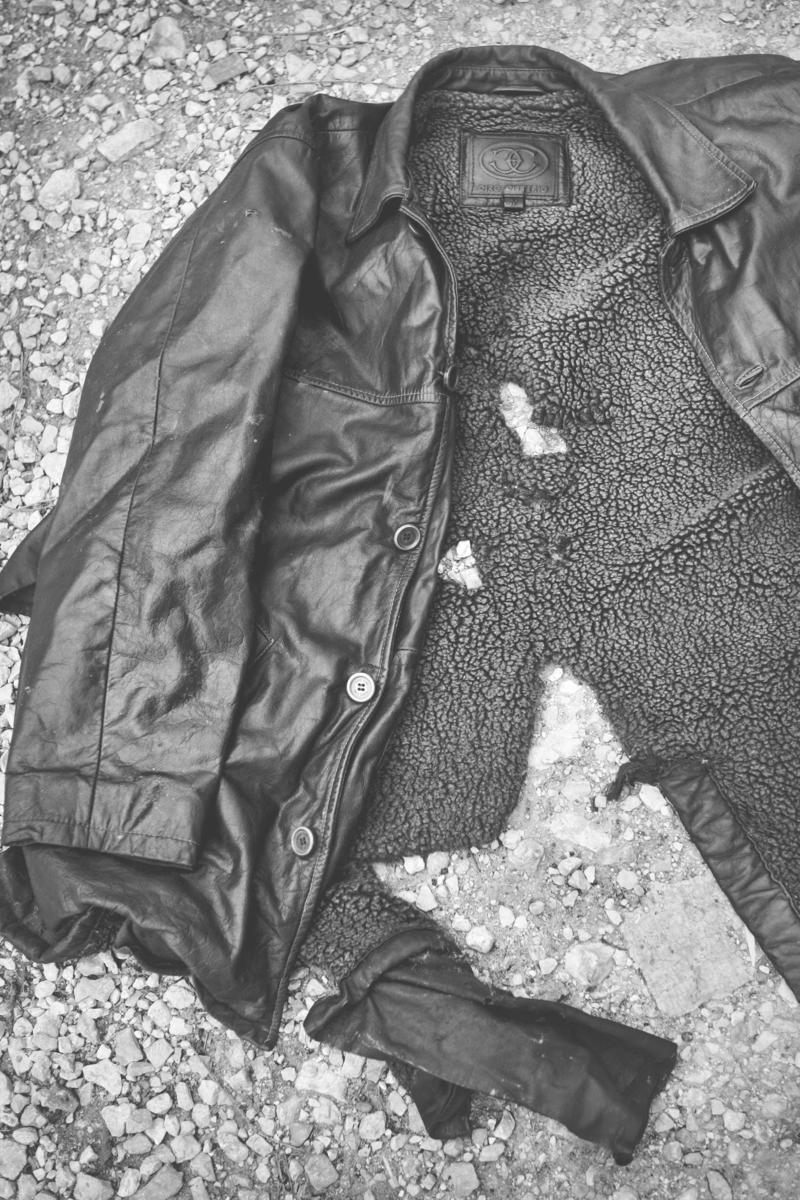

De Visser seems to have resorted to a “one size fits all” formula in presenting her images and textual accounts: whether we are viewing the spectacle of a Palestinian cameraman killed by Israeli Defense Forces in Nablus, the dogtags of a refusenik, the key to the ancestral home of a dispossessed family, or the jacket of a survivor of a suicide bombing in Jerusalem,such objects are each constrained within a uniform aesthetic. Granted, the photographs — by Israeli Associated Press photographer Oded Balilty, who is, by the way, only mentioned and credited in the colophon of the quadrilingual (English, Arabic, Hebrew, Dutch) exhibition catalogue — are beautiful still lifes. Nevertheless, the uniform approach renders the pictures and stories unengaging for the visitor, eventually becoming an exercise in serializing drama. Moreover, the photographs themselves aren’t “action shots” of the personal objects, but staged artistic translations, devoid of any contextual and geopolitical information, let alone the presence of their owners. The singularity of the objects and personal narratives can’t speak within this format, and it’s a pity. The use of static media, such as photography and text, reinforces this and somehow erases the voices of de Visser’s interviewees, transforming them from subjects in conflict to mere constructed objets d’art on display.

For an undertaking seeking to counter media headlines and TV visuals,the choice of medium is decisive.Lebanese artist Lamia Joreige’s ongoing documentary project “Objects of War” (which was not featured in this show) is a case in point. By asking her subjects to talk about an object that, for them, is a symbol of the Lebanese civil war, she literally offers her interviewees a platform to express their own voices, engage in their own authorship. The editing and framing is careful, yet minimal and unobtrusive. At no point does the viewer feel the filmmaker’s interference. On the contrary, Joreige takes on the role of an archivist, a chronicler of untold stories, and a historian. We don’t find that forced aesthetic morphing of personal everyday objects into images for a coffeetable book, as is the case with the Amsterdam show.

De Visser inserts herself into a narrative that isn’t hers. Why, for example,does she insist on including a story of her own about a closed soap factory in the old city of Nablus? Where does that position her? Can a curator, bystander, and observer, within such charged subject matter,simply wedge herself in as a participant? Is it ever justifiable for a curator or an artist to edit and objectify the hardships of those caught up in violent conflict — for motives that are questionable at best? It seems revealing that de Visser’s name is the only one appearing (in huge letters, no less) on the cover of the catalogue.