Dubai

Moving Walls

The Third Line

August 27–September 16, 2006

Something happens when documentary photographs are taken out of the context of the daily newswire and framed and exhibited in a gallery. Somehow the level of news fatigue subsides, revealing images that are immediately more intimate and complex. A web of relationships becomes apparent — between those in front of the lens, between photographer and subject, between image and viewer.

The documentary photography exhibition “Moving Walls” takes the “the world in conflict” as its starting point. Curated by Stuart Alexander and Susan Meiselas on behalf of the Open Society Institute, the exhibition debuted in the US as a show of sixty photographers; whittled down to seven, it then embarked on a tour of the Middle East, the Caucasus, and Asia. In Dubai, the Third Line added local photographer Bendar Al-Bashir to the mix, presented a season of documentary films,and hosted photojournalism workshops alongside the show.

Of course, the media is saturated with images from the Middle East, particularly “hot spots” on the journalists’ beat — currently, and recurrently, Lebanon, Iraq, and Palestine. But it’s rare to see an exhibition of international documentary photography in the region. Thankfully, besides more conventional subjects such as Eric Gottesman’s collaborative work with HIV/AIDS sufferers in Ethiopia,the show’s curators included stories from the US — Gary Fabiano’s understated portraits of homeless people and their possessions; Edward Grazda’s reportage of mosque life in New York in the early 1990s, and Andrew Lichtenstein’s study of life inside America’s prisons.

The show also featured Lori Grinker’s portraits of war veterans, from World War I to Iraq, and two strong stories from Eastern Europe — Aleksandr Glyadyelov’s images of street kids in the Ukraine and James Nubile’s exposé of the myth of ‘liberation’ in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union following the fall of the Berlin Wall.

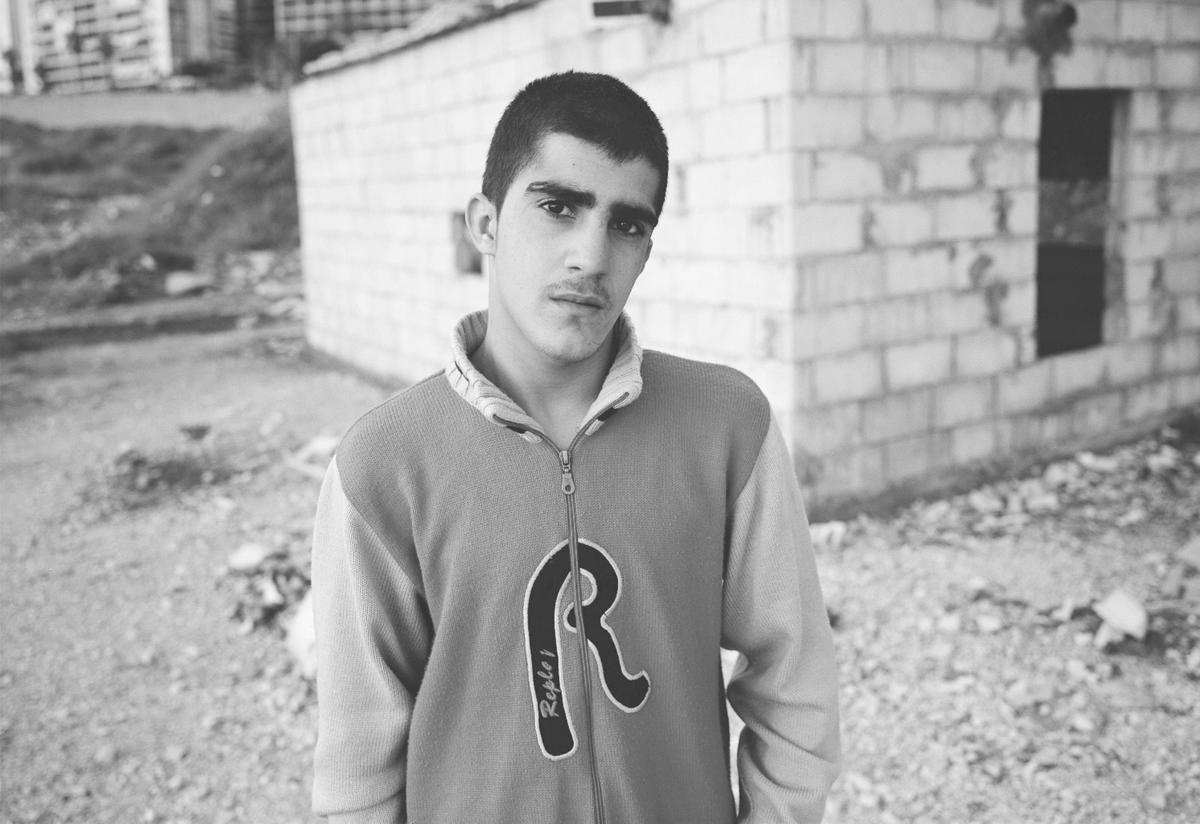

Surprisingly,against images by veteran photojournalists such as Grinker, Nubile and Lichtenstein, newcomer Al-Bashir’s series of color portraits of sex workers, juxtaposed with observational images of their places of work, was outstanding. His work was at home in the gallery: demonstrating a confident use of color, he appeared to eschew the temptation to editorialize his subjects — perhaps he is influenced more by contemporary art documentarists, such as Rineke Dikjstra and Jitka Hanzlová, than by the world of print photojournalism. Krishna and Narenda With Apprentices, a portrait of the teenagers with two boys of maybe seven or eight,is devastating in its portrayal of the cyclical continuum of abuse. Al-Bashir also included a portrait of Mohammed, a teenager from Beirut, with a stark photo of his place of work — a beachhead, strewn with dilapidated fairground cars.

Edward Grazda began his documentation of New York’s mosques in the early to mid-1990s. His use of simple, black-andwhite photography, and his references to the events of September 11 in the wall text, dates the series as if to another age; “we hoped to reveal an alternative image of American Islam,” he writes, almost nostalgically.

Generally, the exhibition did rely on extensive wall notes, captions and, in some cases, statements from both the photographers and subjects — a move that could have jarred slightly in the context of a contemporary art gallery. Indeed, perhaps the subtler work emerged as the strongest. Besides the discovery of Bendar Al-Bashir’s work, James Nubile’s combination of quotations from the Geneva Convention and grids of images from Eastern Europe — portraits, landscapes, studies of graffiti and architecture — allowed for more interpretation on the viewer’s part. One image sticks in the mind: a group of men, some in military uniform, others not, looking down — from embarrassment or respect, perhaps into a grave?

The “Moving Walls” photographers seemed to revel in the freedom they’d been given to indulge in sincere political and social statements. Far from reportage, these are personal statements expressing emotion and outrage.