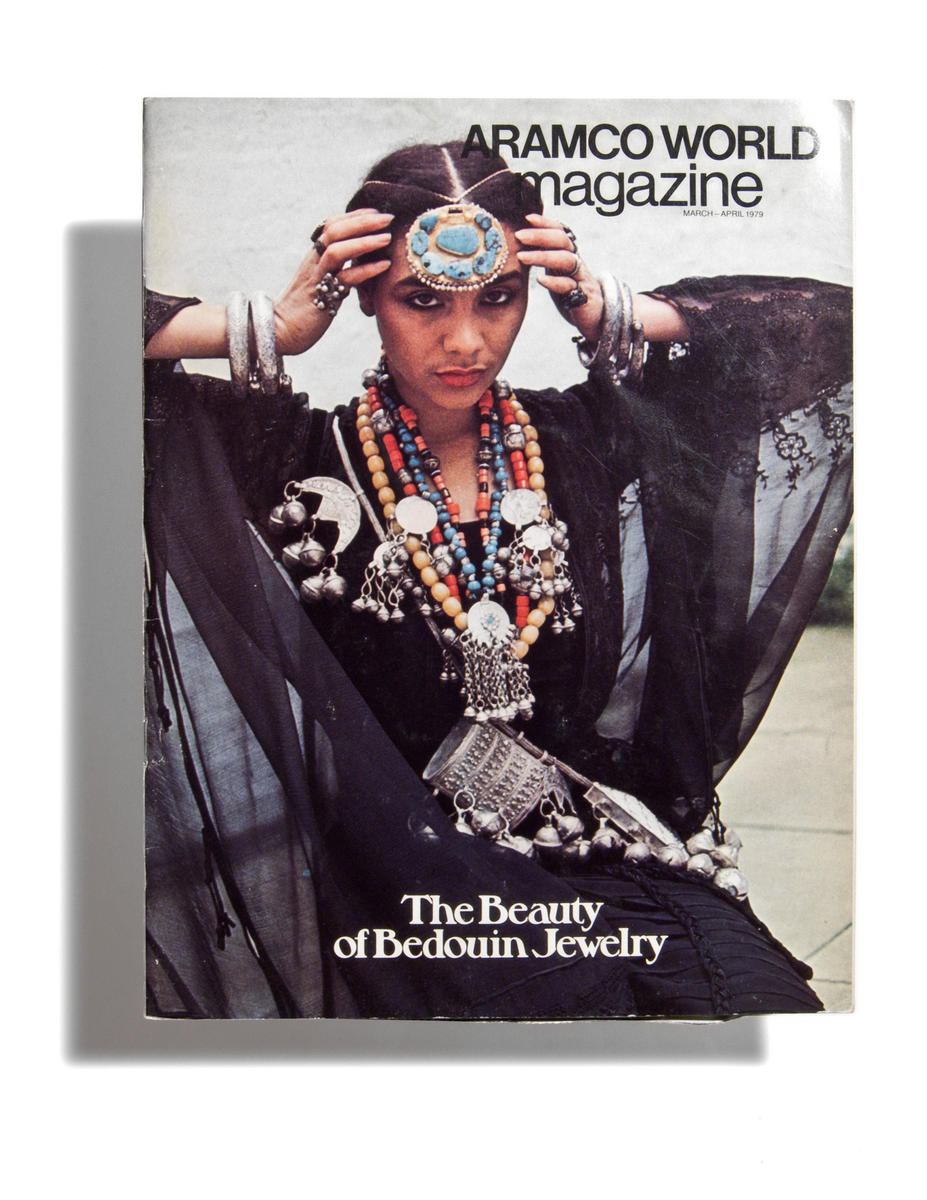

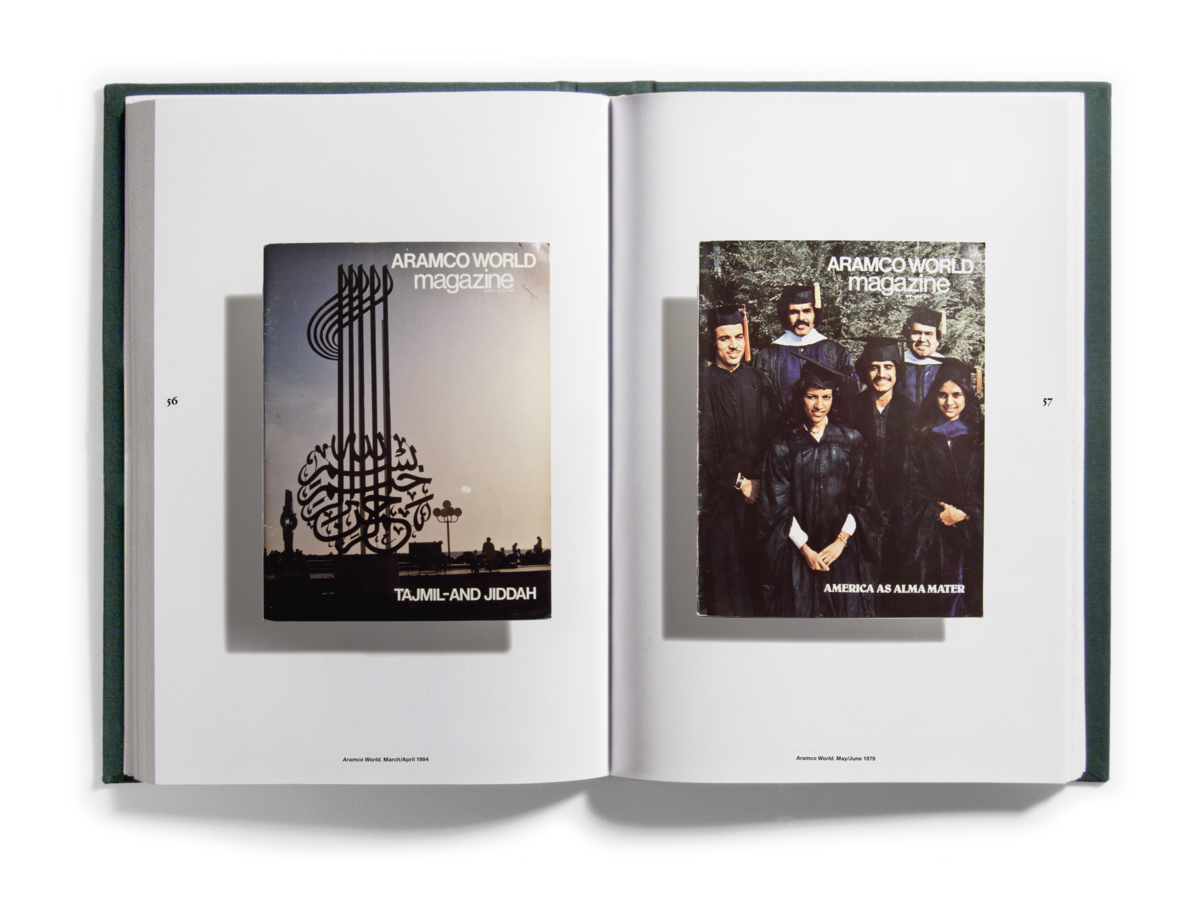

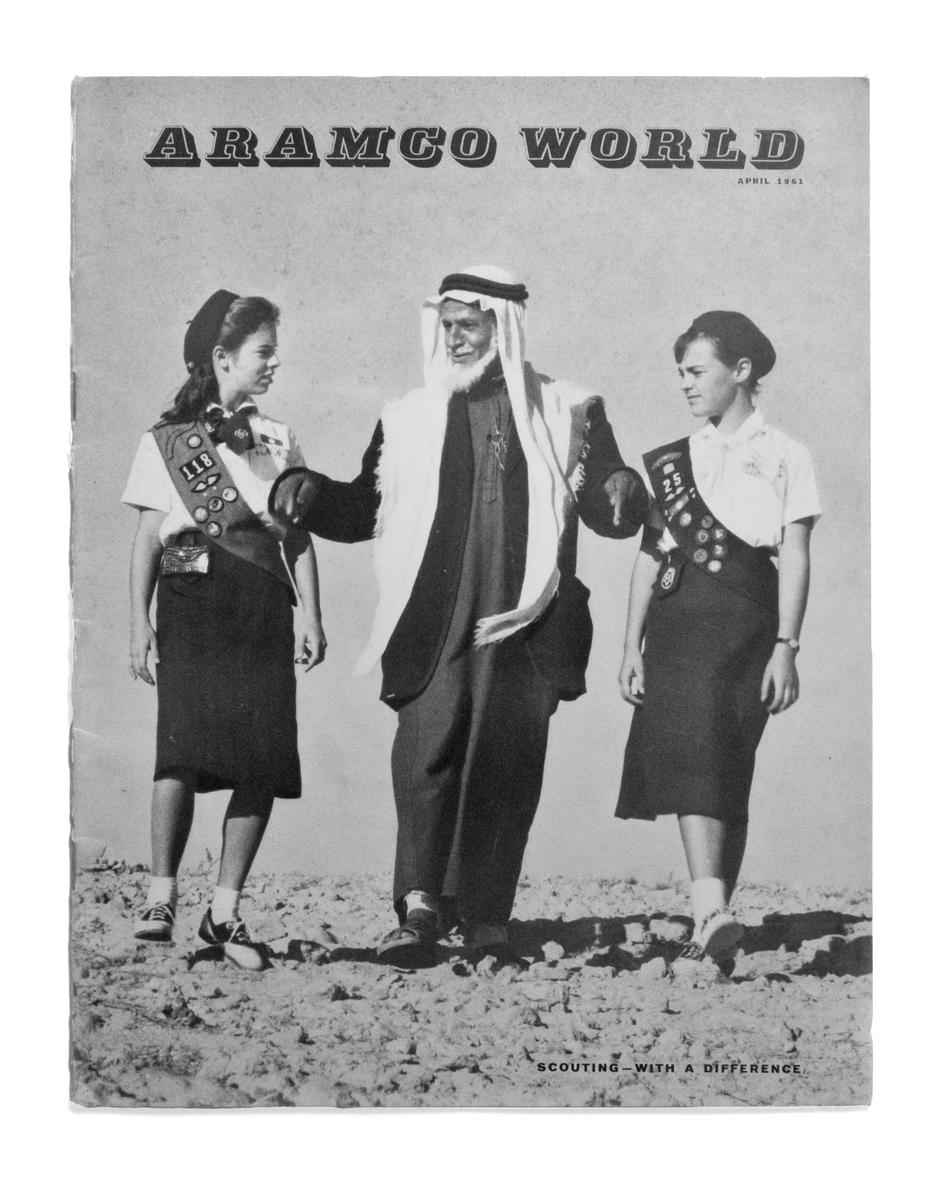

Founded in 1949 by the New York–based public relations department of the Arabian American Oil Company (Aramco), Aramco World is the oldest English-language arts and culture publication in the Middle East. Rechristened Saudi Aramco World some years after the oil company was nationalized, the magazine today boasts several hundred thousand readers. Based over the years in New York, Beirut, The Hague, and Houston, Texas, it has been a curiously indispensable “intercultural resource” for six decades and counting.

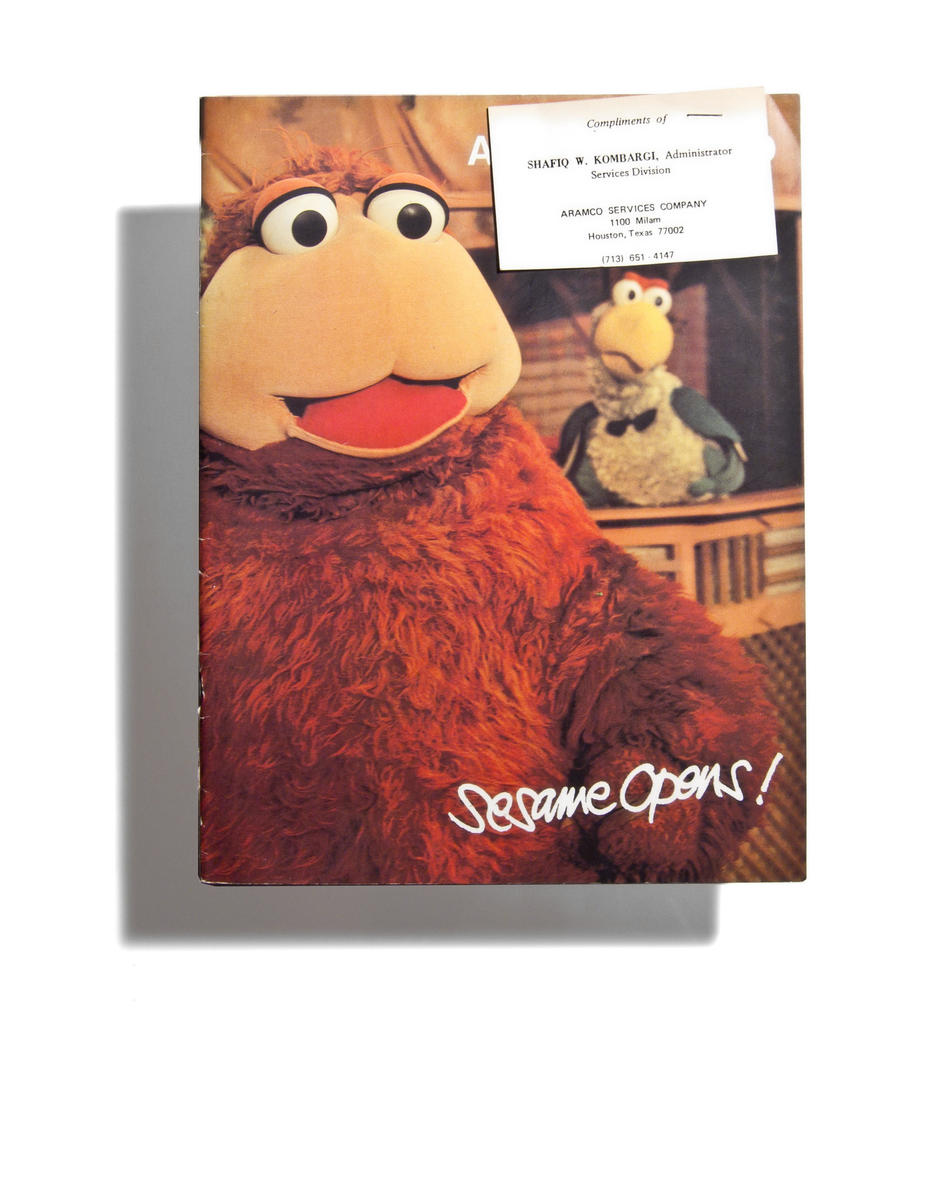

In preparing the latest version of the Bidoun Library, we acquired a heap of copies of Aramco World from the 1960s and 1970s, and we were really just blown away. By the design, the imagery, the stories: I am haunted (in the best way) by that 1979 cover story about the Arab version of Sesame Street. How is it that a promotional vehicle produced and freely distributed by an oil company should have been such a great magazine? Didn’t it start out as a company newsletter?

William Tracy, writer and photographer, assistant editor 1967–1977: It started off as an in-house magazine, talking about bowling and, you know, Wanda in accounting is getting married to Joe in engineering. And they figured that their employees would do a better job working with Arabs if they knew, say, that Arabian horses came from Arabia. So there’d be an article about Arabian horses. Obvious stuff like that. And then popular stuff, like: Wow, did you know Arabs eat ice cream? And that they make it in Damascus? And when they started putting articles like that in the magazine, the employees began to give copies to their kids to take to school, and the schoolteachers would write Aramco and say, “Could I get this regularly? That article about ice cream was really fun for the kids.” So they started tilting toward those more popular articles and sending it to public schools around the country. And gradually it just worked up the scale until it was adults talking about adult things — the idea being that Arabs are real people with art and sports and culture, and that maybe knowing about all that would make it easier to do business.

But it’s always been free for anyone with a real desire to know about the country. Occasionally that would get out of hand — at one point we started receiving letters from Ghana saying, “My teacher said to write and ask for your magazine,” and then suddenly we had requests from ten thousand Ghanaian schoolchildren. It was clearly one of those assignments where the teacher says, “Write a business letter to a company and see what happens.” We ended up sending around three thousand copies. But generally, the magazine goes all around the world. If there’s a special issue on Islam in China, they’ll translate it into Chinese and distribute extra copies over there.

Did you know Arabic?

I would say… I spoke colloquially. I had taken classes as a kid in Saudi Arabia and then I took classes from a Palestinian German lady in Beirut, but a lot of what I knew I picked up from teaching English to high school kids. So I had to be careful. If you ask a fifteen-yearold boy, How do you say “peanut butter sandwich,” he’s likely to teach you some kind of cuss word. You had to watch their eyes when you asked them direct questions like that, and if there was even a hint of a giggle you’d ask someone else later.

How did you get involved?

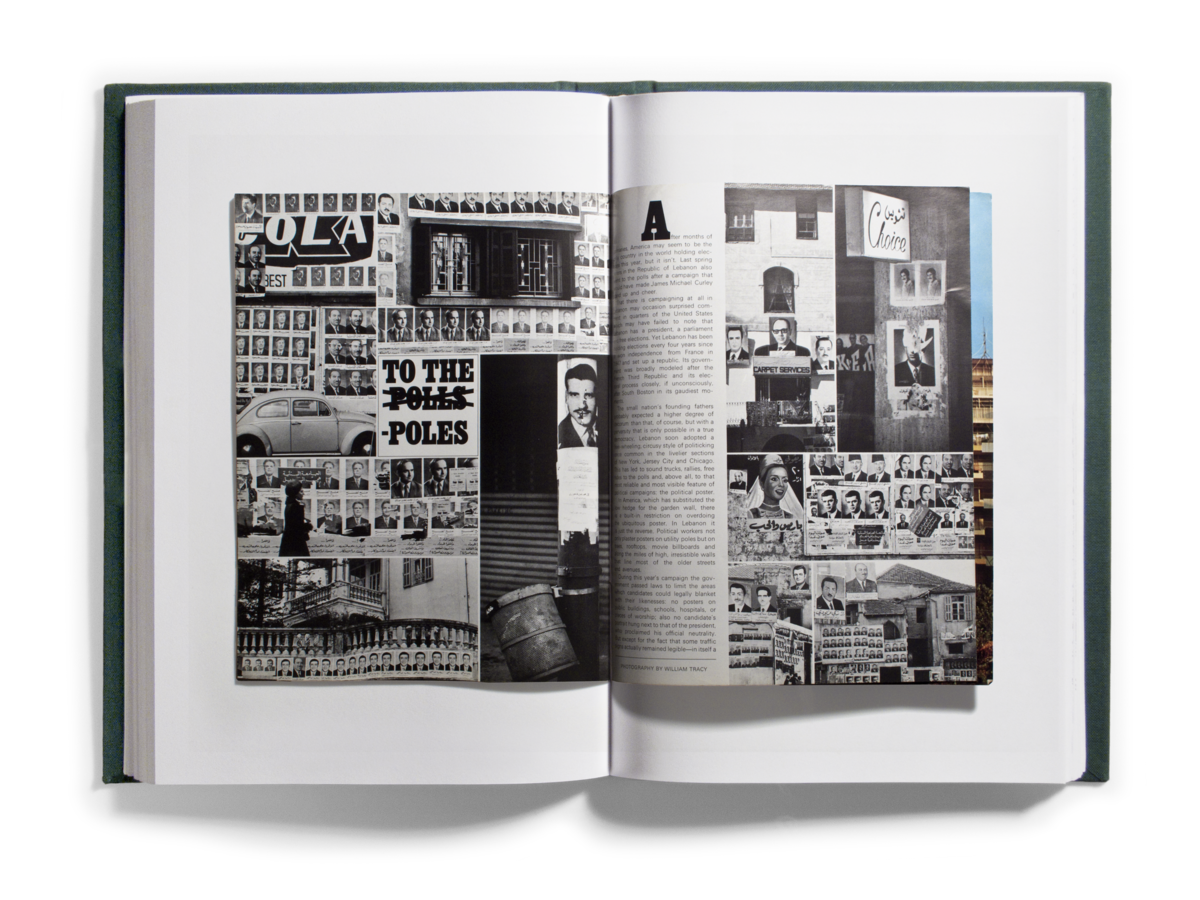

I was in Beirut already, teaching English at the prep school for the American University, when Aramco World opened up shop there in 1964. That was when it really took off, when they hired Paul Hoye to be the editor. Hoye had a background in journalism, and that greatly influenced the magazine in those days — he had a very pop sensibility. He was into fashion, music. Things that were newsworthy, topical. I was a big hiker and I knew that the Lebanese government didn’t like goats in the forest — goats rip things out by their roots, whereas sheep just crop things. So I pitched a story about reforestation efforts in the mountains and that appeared in the second issue they published in Beirut.

Robert Azzi, reporter and photographer: I’d gone to Beirut in 1968. My parents came from Lebanon, so I decided to move to Lebanon that fall and see if I could create a life for myself as a photographer. At that time all the Western media had their bureaus in Beirut — Time and Newsweek and ABC News and the Christian Science Monitor. They were probably all within a ten-minute walk of each other, near the Saint-George Hotel. Aramco World was there, too. And for a young freelancer, Aramco World was the magazine that you wanted to be seen in. In Lebanon the magazines were either very stodgy Arab magazines or very French, celebrity driven kind of stuff. I had no interest in that at all. I’d done a little work with the UN, taking photos of Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan. And then I was introduced to Bill Tracy, who worked for Aramco World. And Aramco World just led to things — it was a way of getting around the Middle East and meeting people. It was a great thing to have in your portfolio.

Did Aramco move the magazine to Beirut because it was perceived as the heart of the Arab world at that time, or some such? I suppose Nasser’s Cairo would not have welcomed an American oil company magazine…

William Tracy: Exactly. Beirut then was an incredible city, a publishing center with a good color printing press and access to an incredible pool of freelance writers and photographers and artists. They say — of course, you never know how much of this stuff is just conventional wisdom or anecdotal — they say that Beirut really boomed because of all the exiles. Alexandria and Cairo had been very creative places. And Haifa had been a big center for the arts, that then that became out-of-bounds when Israel was created. Another place was Marrakesh, I think. As all these colonial eras were ending, Beirut was where everyone moved to. It was full of Lebanese Egyptians, for example.

Did the magazine pay pretty well?

Robert Azzi: They paid well. They were fair. Depending on the story, they’d cover your airfare and expenses — and the fee, of course. I did a whole issue for them once, “The Arabs in America,” and they sent me all around the U.S. to take photographs for what was one of the earliest features on the subject. That was in 1979. That subject became hot stuff after 9/11, of course, but back in those days the stereotypical Arab in America was Danny Thomas, a Lebanese Christian. There wasn’t as much visibility for the Muslim communities in this country then.

How did the editorial process work? Did they mostly assign stories, or did you pitch them ideas?

Robert Azzi: Both. They were very easy to work with. The deal with them was that if you proposed a story and they felt you could do it, it was yours. So those of us who were freelancers would just generate story ideas — there was no Web to surf at the time, so you would sort of surf your circle of acquaintances and guidebooks and the International Herald Tribune and such. So for example, the issue that got banned in Saudi was the result of one of my pitches.

What?!

Robert Azzi: The Georgina issue. In 1971 the Miss Universe title went to a Lebanese girl, Georgina Rizk. I wrote and photographed that story.

William Tracy:It wasn’t banned, actually. It was agreed in advance that the issue would not be distributed in Saudi Arabia. Which was not without precedent — in the early Beirut years, the magazine was only sent to American employees working in the kingdom, not to Saudis. When that changed, it was because of pressure from Saudi students who had gone to the States to get their PhDs and returned home. Once I was down in Arabia to interview the assistant minister of commerce or something for an article, and he said to me, “I’m really offended that I can’t get Aramco World. I’ve tried and they won’t send it to me. I used to get it when I was a student and now that I’m home it’s not allowed?” After that the policy changed.

We went ahead and did Georgina anyway, which is a testament to Paul Hoye the journalist. He said, I know we’re not supposed to have girls in bathing suits in this magazine because it doesn’t follow the custom of our host country. But on the other hand, how long will we have to wait before there’s another Miss Universe from Lebanon? It’s never happened before — what if it never happens again? We can’t take that chance. So he talked to his contact and he made the argument and they said, All right, go ahead, but that particular issue will not be circulated within the kingdom, even to the American employees. That was the agreement.

You’ll notice that Georgina is actually quite discreetly dressed on the cover. Inside there’s a centerfold with her in a bathing suit. That was back when Playboy was a big deal. [Laughs]

Robert Azzi: Have you looked at the Saudi Aramco World Web site? They’ve put everything online.

Actually, everything except the Georgina issue. [Laughs]

Robert Azzi: [Laughs heartily] Georgina is not online?!

You can download PDFs of every issue except that one. [Laughs] Were there other controversies of note? I was interested in Robert’s cover story on Lake Van in Anatolia and the Cathedral of the Holy Cross on Akdamar Island. The photos are really incredible.

Robert Azzi: Thanks. Oh, that was great. I have to say, I had never been exposed to Armenian points of view until I got to Beirut, which was and is intensely Armenian in its cultural life. And my first girlfriend in Lebanon was Armenian. We managed to convince Aramco to send us to Lake Van. My girlfriend Touna was fluent in Armenian and Turkish, which turned out to be important because there were no Armenians left there, just a combination of Eastern Turks and Kurds. When we asked someone about the writing above the door on the church, he said it was an old form of Arabic. They couldn’t bring themselves to admit that the script on the church was Armenian.

But, you know, to Aramco that was a cultural story, part of the history of the region. Nothing seemed off-limits at that time, except maybe Georgina’s legs. I loved that Van story.

Even just the typography — the headlines were very stylized. Maybe in the style of the Armenian alphabet? Or… all those Turkish psychedelic records that were coming out at about that time?

Robert Azzi: Right. [Laughs] Well, Bill knows where the designer lives, so maybe he could put you in touch with him. It would be really interesting.

William Tracy: I could, but Don Thompson lives in a remote village in Southeast Asia, and only goes to town to get mail very irregularly. It might take a while.

So Don Thompson was the art director?

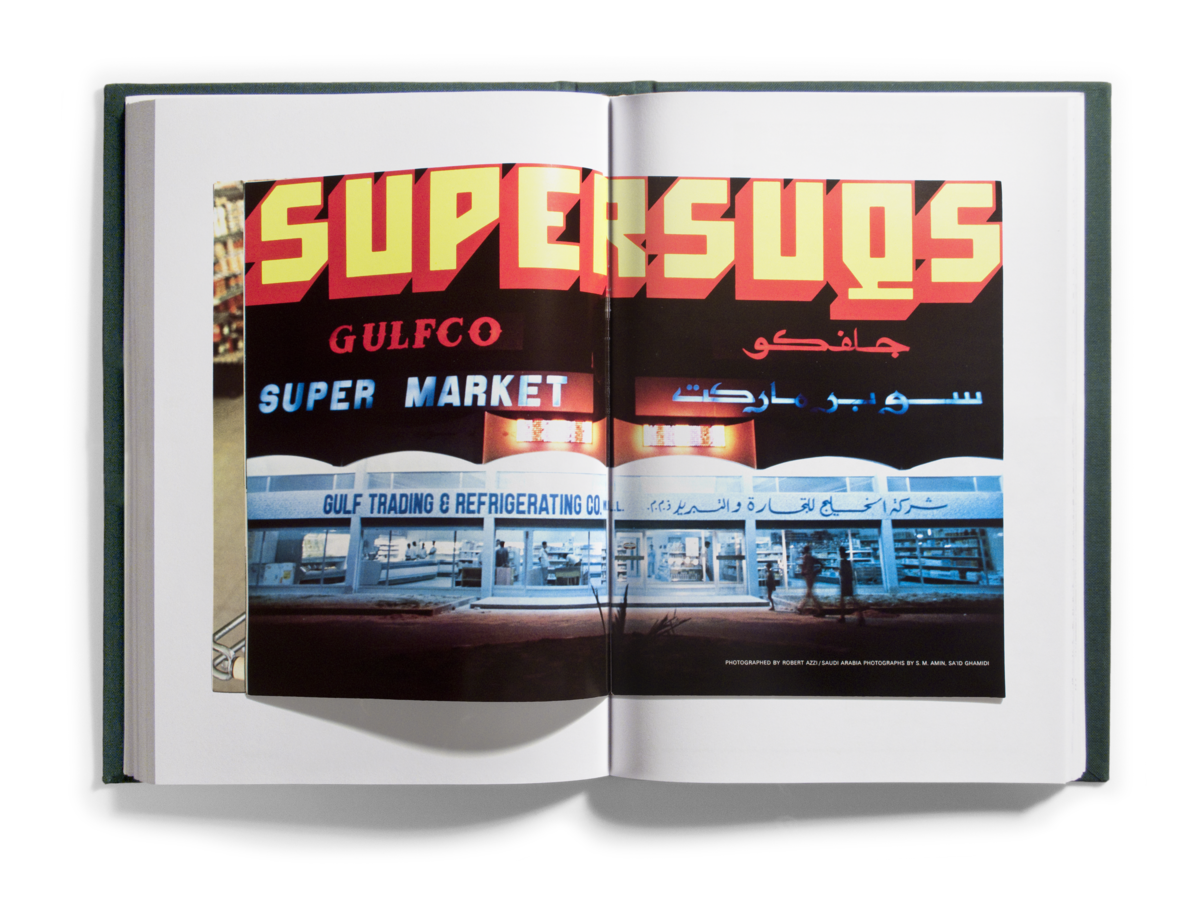

William Tracy: Don Thompson was the designer. He was actually an employee of Middle East Export Press, our printer. This will boggle your mind if you think Aramco World was a good magazine, but our office consisted of the editor, his assistant (me), and our secretary. Full stop. Although we were in the same building as the Aramco Overseas Company, so if we needed help with a passport or to get the electric bill paid, there were people upstairs who would take care of that. But they weren’t really on the magazine staff — we were more of a thorn in their side. But Don Thompson was very important. We never had a relationship with any other designer like we did with Don. In addition to sketching out the layouts and submitting them for our approval, he personally supervised the printing. He’d be on the floor at the press, making sure the color looked the way it was supposed to. He was just incredible. He designed the magazine the whole time it was in Beirut. He was quite a good artist, too — a few issues of Aramco World featured his paintings or drawings on the cover. He’d done his training at the Rhode Island School of Design.

When did he stop designing the magazine?

William Tracy: Well, when we left Beirut, there were several issues in the works already, so Don came to Holland with us, sort of on a loan from Middle East Export Press. At some point he actually joined Aramco proper, and the first thing the people in Dhahran did was steal him away from the magazine. So he moved to Saudi and started designing the annual reports. I was there myself in 1979 and 1980, writing the reports, and he designed them. A few years later he made an extremely early retirement and married a Thai beauty queen and moved very far away from it all. He’s an artist; he had things to do.

Did you ever get interference or pushback from Saudi, Bill? I read in your history of the magazine that there was some kind of review process.

There were very subtle things. If you needed an image for an item about a banquet honoring the president of Syria and you had three photographs to choose from, you wouldn’t use the one where everyone is standing with their wine glasses at their mouths. The wine glasses might be at their sides or on the table. Just that kind of very little subtle thing. Or you would talk about issues — “There are those who would like to see more emphasis on girls education” — but only in a general way. You would avoid opportunities to say something negative about a personality or a minister. Other than that we had tremendous leeway. But there was a review process, it’s true, and at first it annoyed the hell out of Paul Hoye. This was in the days before e-mail — before computers, actually, and before faxes. We felt very up to date because we had telexes. But in the early days of his tenure, you’d have to send things by company courier. Aramco had its own airplanes, so once a week he’d put a stamp on any story he was going to send over with little check boxes, “approve” or “disapprove,” and a whole distribution list: senior vice president, general manager, manager, supervisor of publications. So it would first go to the senior vice president and if he checked “disapprove,” then duh, everyone underneath would disapprove, too. This was not something particular to Saudi Arabia — I don’t know if you’ve ever worked at a large company in America, but the number-one rule in any company is “Cover your ass.” So Hoye had the brilliant idea to send each person on the list their own individual review copy.

Looking back on the old issues, it seems like there are certain things that didn’t really get talked about. There’s not so much, for example, about Palestine.

Robert Azzi: There were things that did not get talked about. I think that it wasn’t so much about the Palestinians so much as that if you dealt with Palestine, you would have to deal with Israel. You would have to get political.

William Tracy: Certainly when I did the issue on “Arabs in America,” there were Palestinians in that issue. More than half a dozen… But not everybody was identified by their ethnicity. More recently I think there may have been a feature on Palestinian embroidery.

Back then we all knew that Aramco was going to be nationalized at some point. It was just a question of time. And the Americans were not going to do anything contrary to Saudi political interests. So the magazine steered away from political stuff. But in any case, Aramco World saw themselves as a cultural project.

One might say the same thing about Bidoun.

Aramco World really saw itself as a cultural interface between the Middle East and the United States. I think there was prescience in that, the idea that greater understanding of the people and the issues of the Middle East would be important in the future. Although I’m not sure that worked out quite the way any of us expected… [Laughs]