Mona Eltahawy has a knack for inspiring hatred. Egyptian activists and bloggers have called her an alien, man-hating, woman-hating, out-of-control psychotic. Non-Egyptian bloggers have called her a Muslim Nazi bitch. Pam Geller, the fulminator behind the Ground Zero Mosque scare, called her a “fascist savage.” A cover story on “misogyny in the Middle East” for Foreign Policy — titled “Why Do They Hate Us?” and illustrated by images of nude women painted black, only their eyes showing, like human hijab — generated tens of thousands of angry words in response. Sondos Asem, the young female spokesperson for the Muslim Brotherhood, decried her “one-dimensional reductionism and stereotyping.” There were parodies, character assassinations, death threats. Most people would wilt in the face of all this vitriol, ridicule, and angst.

Most people are not Mona Eltahawy.

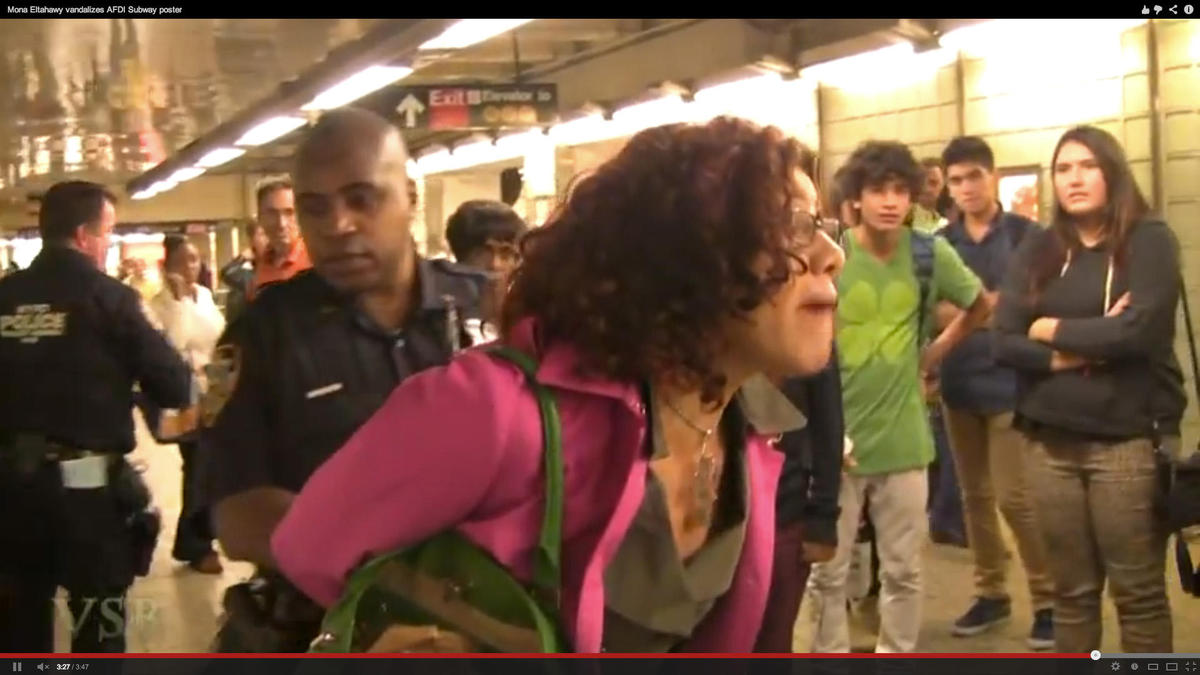

Eltahawy, a journalist-turned-pundit–activist, seems to rather enjoy it. Since the revolution broke out in Egypt on January 25, 2011, this media-savvy New York–based Egyptian has fashioned herself its global spokesperson. And in the intervening two years, she has found a new career as a provocateur. Besides her numerous articles, she has taken her activism into the proverbial street. In November 2011, she took part in the protests on Mohamed Mahmoud Street in Cairo; an ordeal with police and military intelligence followed, including a sexual assault and broken limbs. In September 2012, she defaced a Geller-sponsored advertisement in the Times Square subway station (“IN ANY WAR BETWEEN CIVILIZED MAN AND THE SAVAGE, SUPPORT THE CIVILIZED MAN. SUPPORT ISRAEL. DEFEAT JIHAD”) with hot pink spray-paint, before being dragged off by transit police.

As with most everything else she does, these provocations are documented exhaustively on Twitter.

I should say that I went to meet Eltahawy in Harlem last November still outraged by her Foreign Policy article, and by half a dozen other things she had written. I arrived at a café near her home prepared for a fight. Mona — everyone calls her Mona, whether they like her or not — unhinges many of us with her seemingly boundless self-regard, her bluntness, her eagerness to court controversy, and her — well, her one-dimensional reductionism. But in person, I found myself disarmed by her honesty and her thoughtfulness. She has a quite nuanced understanding of the criticisms leveled against her, even as she strenuously rejects them. By the end I found myself admiring the very shamelessness and outrage that makes so many of us uncomfortable.

At one point in our exchange, Eltahawy described her night in jail after the subway graffiti incident. After a period of discomfort and mutual distrust, she bonded with a cellmate, comparing life stories and tattoos. And they joked about the unlikely pair they made: the drug dealer and the protest-itute.

Yasmine El Rashidi: You had a day in court yesterday.

Mona Eltahawy: Yes, you caught me at a great time… . They offered me a plea deal that would guarantee me no time in jail, but I turned it down — two days in community service and two fines, including my favorite, which is almost eight hundred dollars for the Gucci sunglasses of the woman who came between me and the ad.

YER: What is the exact charge?

ME: Charges: criminal mischief, possession of a graffiti instrument, and making graffiti.

YER: You woke up that morning, September 26, and thought, I’m going to spray-paint that ad?

ME: Oh yeah. I had business meetings that day and it was very frustrating to me that I couldn’t go immediately over to the ads that morning. But at least I had a lot of chances to tell people, “Look, I’m going to go spray-paint this ad and I might get arrested today, so don’t worry if you don’t hear from me for a long time.“ I was texting and direct-messaging friends on Twitter all day.

YER: So you knew that you could get arrested.

ME: Yeah, and I’m still going to plead not guilty because I don’t believe I did anything wrong.

YER: You wanted the attention…

ME: Absolutely. I wanted to get arrested. The way I looked at it was, those ads cost six thousand dollars. I don’t have six thousand dollars. What I do have — my capital is not financial, it’s my media profile. People know who I am. So I was not in a position to create an alternative ad — people said that’s what I should have done. And in any case those alternative ads people were making, as on point as they were, weren’t challenging enough. They were too polite. I was so frustrated, especially by what was happening on Twitter.

YER: On Twitter?

ME: My initial frustration was with Twitter. People were just venting about these ads. And believe me, I love Twitter. Love it. I live on Twitter. But there are times when you hit the wall and you need to get out. Like the revolution in Egypt. Against these ads, you need people on the ground, making it socially unacceptable to be racist and bigoted. We need a revolution, not alternative ads. I’m too angry for alternative ads.

YER: What are you angry about? Or is it a general state of being?

ME: You know, Yasmine, over the past few weeks I’ve truly been unraveling. It was the anniversary of the attack. I went back to Egypt for it, joined the Mohamed Mahmoud Street marches and memorials on November 19. So I’ve been feeling very torn up. The past few weeks have been the worst in my life, worse even than when I was attacked. I’ve been so low on energy and inspiration. At my rock bottom. But what happened yesterday in court completely reenergized me! It brought me back to life, because it reminded me of why I did what I did. It reminded me of the many fights I’ve had — and it reminded me just how much I love to fight. I love to fight! [Laughs]

YER: Following you on Twitter, one might think you live to fight?

ME: I think that those of us who are privileged enough to travel between cultures, to travel globally — one of the ways we can be most effective is find the place where we are a minority and poke away at those places. So in Egypt, for example, it’s a minority position to say that you are secular and want to keep religion out of politics. It’s a minority position to be a radical feminist. To say that they hate us, and that is why we don’t have any rights. I’ve found that for me that’s the most effective thing, to poke at the painful places.

YER: But you live in America.

ME: Yes, and here I’m in the minority as a Muslim. So I’m a secular, radical feminist Muslim, and people have to accept that. And the spray-painting is a part of it. I mean, all the protests that have happened over the past few years — the Danish cartoons and all that — including the ones against the ads over the summer, are most visibly led and promoted by a very right wing among Muslims. And they are most visibly promoted by a very right wing among non-Muslims, as well. What I try to do with my work is to place myself between the two right wings. And what I hope to do with this protest in the subway is to take that sense of ownership away from them — to say that I am offended. Even a Muslim who looks like me, with my pink hair and tattoo, who defended the Danish newspapers’ right to publish those cartoons, is offended.

YER: Your critics say that you conveniently switch between your many identities to suit the news of the moment. American? Egyptian? Muslim?

ME: We all have multiple and layered identities. The American in me, for example, believes that what I did is part of the long line of civil disobedience in this country. The only way this country has changed is through civil disobedience. From the civil rights movement to the protests against the war in Vietnam — they all involved breaking the law out of principle. And that’s what I did. I wanted to get arrested. I did it out of principle. And I would do it again.

ME: I knew you in 1997. You worked at Reuters, had dark hair, no tattoos, you dressed somewhat differently. And you seemed sort of… timid? What happened? [Laughter]

ME: I think I’m just much more visible in my fight now. I think what has happened in my adult life is that the fight that has always been internal has externalized itself, more and more. I mean, I wore hijab for nine years.

YER: Yes! I thought I had a memory of that.

ME: Oh yes, from sixteen to twenty-five I wore it by choice. And that speaks to the kind of pressure that women are under.

YER: You were pressured to cover your hair.

ME: We moved to Saudi Arabia from the UK when I was fifteen. (We had left Egypt for the UK when I was seven.) It was a huge, huge, shock to my system to go to Saudi. The way the men looked at me was just horrendous. We went on hajj soon after we arrived, and I was groped beside the Kaaba, as I was kissing the black stone — the heavenly white stone that was tainted black by the sins of humanity. I was fifteen, it was the first time in my life I was dressed like this — like a nun — going to perform one of the five pillars of Islam in the holiest place on earth for Muslims. And I was groped! This guy has his hand up my ass as we are doing tawaf. I had never been touched in any sexual way before — I didn’t know what to say. I burst into tears. It took me years to tell my parents what had happened. Maybe ten years. I was so ashamed, even though I had nothing to be ashamed of.

So I got very difficult and troubling messages about my body. Which is why I have a lot of trouble with niqab, because that’s how it started with me. I felt so violated I just wanted to hide. And it’s very wrong, that the way we feel we can protect ourselves is to hide. It goes right back to what’s happening to women in Egypt today — women are blamed for sexual violence. They are told, “If you cover up, you will be okay.”

YER: But you uncovered, eventually.

ME: When I put on the veil I literally thought that I was striking a deal with God — “They tell me that I should cover my hair to be a good Muslim. Well, I’ll do that, but please help me not go mad.“ And I was going mad. For many women hijab is an integral part of their identity and they’re very comfortable. I respect that. But to me it was very uncomfortable. The internal me and the external me were so far apart. It took me eight years to take it off. And the fight you see today is one I’ve had inside me all along, it just needed all this time to become so visible.

YER: You wrote an article in Foreign Policy last spring that made people very, very angry: “Why Do They Hate Us?”

ME: There was no sinister plot, like people think. It’s really simple. They wrote and asked if I would like to write a piece on women’s rights, and I said yes. And I think it’s really disingenuous of the people who are asking why I wrote it for Foreign Policy, and why in English — it got to them, didn’t it? It found its intended audience. Secondly, no Arabic-language publication would ever have published that, and none would have invited me to write it. I used to write in Arabic. I had a weekly column in Asharq Alawsat, until they banned me.

YER: What happened?

ME: They never give you a reason, they just drop you. But it might have had something to do with the anti-Mubarak Kifaya protests in 2005. I had been called into state security for an op-ed I wrote in the International Herald Tribune entitled “How Egypt Hijacked Democracy.“ Anyway, the point is, I have experience with Arabic language media and I know they would never touch this subject, especially since I wanted to talk about religion and culture and how it creates this toxic mix, this mess we live in. And in the age of social media, I found that the people I wanted to reach were exactly the ones I reached, because the piece was available online.

YER: I woke up one morning and logged onto Facebook or Twitter or both, and that piece was everywhere.

ME: I know! It’s like I set the world on fire!

YER: So you were happy with the reaction?

ME: It was an interesting and gratifying and grueling experience. The attacks were very personal. As a writer, I know that on any given day, twenty-five percent of the people will disagree with what I say. But it’s the way that they disagree that makes it really interesting. It would be an interesting experiment to change the byline on that piece and see how they would react.

YER: But let’s face it, the images were offensive — chosen, it seemed, by that very right-wing contingency you spoke of earlier?

ME: I know many people reacted in a very gut way to them, but I had nothing to do with the images. I didn’t choose them. They didn’t run them by me.

YER: Were you surprised when you saw them?

ME: You know, overall, I’m very proud of the piece. I’m very pleased with that piece. And in fact I’m going to write a book based on it over the next few months. So for those people who say I generalize and skim the surface, well, it was only three thousand words, and now I’m going to turn it into sixty thousand.

YER: People are going to love that.

ME: I want my book to be called Headscarves and Hymens, because for a very long time I’ve been working on a theory that we women from our part of the world are identified by what’s on our head and what’s between our legs — the presence or absence thereof. What do you think? [Laughs]

I obviously want to provoke. I’ve been writing for more than twenty years, I know what I’m doing. With that article, I wanted to provoke and I was very gratified by the response. I’m glad that it hit people in the gut, because it’s outrageous what’s happening. I am astounded that people are more outraged by what I wrote and how I wrote it and where I wrote it and how it was headlined than they are about what actually happened to the women I wrote about.

YER: We have a knee-jerk hypersensitivity to the West.

ME: The irony is that we have this hypersensitivity while at the same time we are always saying, “You don’t matter, you are not the center of our universe.” That sensitivity makes them the center of our universe. That’s another reason why I wrote it for FP.

YER: The love-hate-need problem.

ME: I made a point in that piece that I think is important. For that audience, which includes foreign policy pundits and diplomats — you are going to be sitting down with our government, which is largely dominated by Islamists, and they will tell you to mind your own business. That the way we treat our women is religious and cultural. That you can’t interfere. And this is where the international community has to stick to its conscience, because there are international standards by which you have to treat human beings, including women. And if you don’t treat them by those standards then you have to be willing to say, We aren’t going to do business with you. We’re going to boycott you. This has to happen. We as women are always being sold out. We’re sold out before anybody.

YER: Like Saudi Arabia and America?

ME: Exactly! How can you have a strategic ally that treats fifty percent of its population like children? It’s gender apartheid. The world boycotted South Africa. If the world can boycott South Africa, it can divest from Saudi.

YER: But the US props up Saudi because of oil. And it’s now propping up the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt in the name of long-term stability…

ME: Absolutely. The US props up any government that will guarantee stability. They supported Mubarak before the Brotherhood. Anyone who guarantees that oil will flow freely and the Camp David agreements will remain untouched. I don’t see a sinister plot in which Obama sat down and said he would help the Brotherhood rise to power, I really don’t. What I see, and what I hate this administration for, is him asking, “Who’s going to keep everything running so that our interests aren’t jeopardized?“

And that’s where, as an American, I say, “This is a fucked-up foreign policy.”

YER: But you voted for Obama?

ME: I voted for Obama because I was standing up to the Christian Brotherhood of America. And if these old, ultraconservative fundamentalist lunatics could be defeated by a coalition of women, youth, and minorities here in this country, then why the hell can’t we do that in Egypt? That’s our responsibility. We didn’t need America to get rid of Mubarak. And please quote me on this — as an Egyptian American, I say, “Fuck the Americans. Who are the Americans? We are in charge. We control our destiny, not the Americans.“

YER: You’ve often been criticized for what people see as serving Western policy makers the kinds of narratives about Egypt and the Middle East that fuel stereotypes. Are those the people you want to reach?

ME: I reach people who speak English, yes, and I have a large following in America, it’s true. But I’m also reaching people who speak Arabic. A lot of people on Twitter — the very same people who were angry at me over that Foreign Policy article — they were venting on Twitter and Facebook in English. They speak Arabic, too.

I wrote that essay understanding very well that I’m privileged. And I wrote that essay trying to look beyond my privilege. I wrote that essay to address people who are also privileged, and to ask them to look beyond that privilege.

I was interviewed by BBC Hard Talk a few weeks ago, and one of the questions that Stephen Sackur asked me was, “After what happened to you, where they beat you and broke your bones and sexually assaulted you — don’t you think that this essay was written out of personal anger?” Of course it was written out of anger, just not the anger he was talking about. My anger was a product of the realization that if I wasn’t who I was, if I didn’t have the privileges I have, I might very well be dead. If I didn’t have a high media profile, when I sent out that tweet saying I had been arrested, Al Jazeera and the State Department wouldn’t have picked up my story. Certainly not as quickly as they did. This hashtag #freemona wouldn’t have started trending globally in fifteen minutes. I probably would have died or been gang-raped or something horrendous.

I was so disheartened and angry by those people who verbally attacked me. We have to look beyond our privileges and see how horrendous it is to be a woman in so many parts of the Arab world. Clearly the women I’m writing about are not going to read my Foreign Policy article, and even if they did, so what? They’re not the audience. That audience, my audience, is those who know how bad it is, and yet their privilege prevents them from being outraged enough. And it’s that outrage that will make our revolution really succeed. The revolution to get Mubarak out of our heads! Mubarak is still in our heads. He’s called Morsi now!

YER: I know. It feels, at times, like it’s a farce….

ME: It is, it is! And it couldn’t have happened any other way because we had nothing else available. The revolution is not over, but it will not succeed until we get women involved, too. That’s the social and cultural revolution.

YER: Many say that the Muslim Brotherhood will serve as a catalyst for the real revolution.

ME: The Muslim Brotherhood is going to help really pinpoint this. You hear how Morsi talks. You hear how the Salafis talk. You see how women are addressed in the constitution. Mubarak is still up here. [Points] He’s in prison now but still terrorizing our minds. Unless we get him out of our heads the revolution is fucked.

YER: Just the Egyptian revolution, or are the Tunisians and Libyans and Syrians angry enough?

ME: In Tunisia, Bouazizi was angry enough to set himself on fire. And that’s the analogy I set up in my essay. And in so doing, he ignited these revolutions. The revolution he started has to be completed by women, because that’s what will create the kind of shift I talked about in the US, where half the population stood up to the old ultraconservative men.

YER: You just came back from a visit to Cairo. From what you saw, what do you think it will take?

ME: For the longest time, the Brotherhood has been surrounded by this protected halo of religion, which they utterly abuse. You know how sentimental people are about religion — you can’t touch it. Well, once they created a political party and moved away from just a wishy-washy ideology, then it became fair game. Once they entered politics and the dirt of politics, became tainted by politics, they came to deserve all the things we chanted last week — that the people want the fall of the regime.

YER: What do we do?

ME: The first step is to break the halo of the sanctity that they surround themselves with. This religious thing. Egyptians have to recognize that they are religious and have faith and that they don’t need the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafis to give them this patina of faith and purity. We don’t need them to represent us religiously. The revolution will truly continue when we recognize that they are not our consciences but our elected representatives.

YER: And women?

ME: Well, when it comes to women, I don’t know if the shift is happening enough. I see more and more coalitions being formed and people on the ground wanting to protect women, but I also see this bizarre, bizarre, rage — and these weird combinations of power and sex — in which young men who are courageous enough to face up to our brutal police force, even as they are making their escape from the shooting and the tear gas, manage to find the wherewithal to think, “I’m going to grab her ass.“ How?! It leaves me speechless. That’s the shift we need to work on. We need to address this horrible cocktail, this toxic mix of power and sex. These men are high on courage and power. They are the barrier we have to address. They are the mini-Mubaraks.

YER: So what happened to those mini-Mubaraks during the eighteen days of uprising in 2011? Why were they so respectful of women in the square? Because Tahrir seemed a somewhat utopic place, didn’t it?

ME: I wasn’t there for the eighteen days the way you were, and I heard from people what you say — but I also heard from people that there was a reluctance to talk about any sexual assault that was happening because people didn’t want to taint the revolution. I understand that kind of power, because it took me a very long time to be able to look at the revolution objectively because it was something I, like so many of us, had wanted for such a long time. Egypt is a very misogynistic country and that was not going to go away after eighteen days. That’s the social revolution that I’m talking about, and the one that interests me much more. I’m not interested in the politics. I’m interested in the personal as political.

YER: In a conversation with Gloria Steinem at the Hammer Museum in late 2010, an Israeli woman in the audience said that it is very easy for you to be sitting in your New York apartment speaking about the situation in the Arab world, but why aren’t you there, on the ground, fighting the fight? You got very, very angry. But many of us have wondered that — why aren’t you living in Egypt?

ME: It’s a legitimate question, and I’ve been asked it many times, it’s true. But the answer is varied. First of all, I’ve reached a stage where I can get the message out about Egypt without having to be there. And there are enough people on the ground to keep all this going without me personally having to be there. It didn’t need Mona there to tip the scale. I felt at that time, during the eighteen days, I could contribute more by being here and literally shaking the media. People said I was literally jumping out of the TV. You know I would go on CNN and the BBC and I would challenge them — they had headlines like CHAOS IN EGYPT and I’d said to them, “This is an uprising, this is a revolution, stop saying chaos in Egypt! This is the most important time in my people’s lives!” And then the New York Times and Michael Moore said five minutes later they changed it to UPRISING IN EGYPT. If I can do that, then I feel I’m contributing much more here then there.

But I have come to realize over the past two years that the social revolution is much more important to me than the political one, and that to do what I really want to do I have to be on the ground. So I’m actually moving back, next month.

YER: Do you feel that you will get a warm reception in Egypt?

ME: I don’t speak for anyone — I only speak for myself. But in doing so, and in becoming so visible with my speaking, I know I represent something that needs to be there in Egypt right now. So many young men and women come up to me, and we have these conversations that are very important. For that I need to be back. And I need to write this book.

But in going back I can’t lose my connection to here, either. To keep Egypt on the international stage, I need to keep my connections here. This poster that I spray-painted in New York — hardly anyone recognizes me here. But in Egypt, it was insane, insane. I was waiting for a cab in the street and a woman got out of her car and said, “Are you Mona? I need to shake your hand, I’ve watched that video ten times, let me give you a lift.“ She stopped her car, on the corniche!

YER: Could you actually tell us the story of the attack, just for the record?

ME: I was at a conference in Morocco, and on the night train from Tangier to Marrakesh. It sounds very romantic, but I spent all those eight hours on the top bunk of the sleeper compartment on this train just crying, following the news from Mohamed Mahmoud Street in Cairo, where there were clashes. One woman tweeted about how this older man came up to her and said, “What are you doing here?” and she told him she was fighting like everyone else. And he said to her, “No, your place is back there in Tahrir. You’re educated — Egypt and its future need you. I’m poor and uneducated and I’m probably going to die here. After we finish what we’re doing here, Egypt needs you to rebuild it and lead it to the freedom that we’re fighting for here.“

YER: Goose bumps.

ME: It gives me tears just thinking about it. And then there was this awful picture of a father in a morgue who had just identified his son. It just tore me up. And then finally there were all these stories coming in of boys as young as twelve years old, probably street kids, some Ultras — who have my ultimate respect since they’ve been fighting the police since 2007 — going into Mohamed Mahmoud knowing they might die. They were writing their mothers’ phone numbers on their arms — so that if they ended up in the morgue, people would know who to call.

YER: So you went back to Cairo.

ME: I’d arranged to meet an activist friend outside the Mugamma. Just before I left the hotel my brother called and begged me not to go to Tahrir. He said a relative of ours had just been killed. He was one of the two people who had been killed in Alexandria a few days earlier. He was in his thirties, the father of two young girls — shot dead. I promised my brother I would stay out of trouble. Instead I went straight to Mohamed Mahmoud to meet my fate.

Well, not straight — we had to take a side street because they were blocking the Mohamed Mahmoud crossroads. We went through Bab El-Louk. There was a battle happening right at the main gate of the American University — sirens, tear gas, all this stuff. I was tweeting all this time, and at one point my friend Maged turned to me and said, “Mona, your life is worth more than a tweet, put that thing away.” So I put my phone away, and we made our way to the front line.

And we’re there, driven by adrenaline, pushing forward, past the ambulances, ducking from the tear gas, pushing, pushing, pushing. We went literally up to the metal barrier. And so I stood up on this rock that was there and I took pictures of these bastard security guys on the other side. Then this man takes my hand and says, “Stand up and take pictures, I’ll hold you.“ I thought it was a bit odd that an Egyptian man was offering to hold my hand like that, but I kept going. And then they saw us and started shooting, so I ducked, and they stopped. These guys next to us were like, “Run!” So we ducked into a tiny fast food place.

We now know that they were mundaseen — plainclothes thugs. We didn’t know this at the time. We thought they were with us. So we ducked, ran into the shop, and all this time the guy was still holding my hand. And then he started trying to take my smartphone. And I’m like, “Leave my phone, ya hayawan, ya hayawan“ (you animal). And here we are, cramped in this small place, and one of them gropes my breast! So I start hitting him. We’re being fired at and he has the headspace to grope me!? And Maged is like, “Mona, we have to go, this is not the time.” But I’m like, “No, no, I’m not done.“ I was punching him so hard that one of his co-thugs actually tried to protect him from me because I was so enraged.

And then suddenly, there were riot police around us and everyone disappeared. I thought Maged had gotten away, but they’d actually taken him to a place where he could see me being beaten, and they were beating him there. So I’m in the shop, and I’m thinking, it’s just me and these guys, I’m a woman, what are they going to do. Ha! Beat the living daylight out of me is what they did. They were whacking me on the head and I was trying to protect my head with my arms, which is why this bone broke, and this bone broke. [Gestures] They beat me so hard that the bone broke inward, like this.

So after this beating, during which I dropped my smartphone, they took me into this room on their side of the barrier, where they sexually assaulted me. Hands here, hands here, hands between my legs, hands in my trousers. I’m literally plucking hands out of my trousers and saying No and they’re beating me, pulling my hair, calling me a sharmouta (slut). And in the middle of all this beating, I fall to the ground. At first I wasn’t sure if I remembered correctly that I’d fallen to the ground, but then my bum hurt so much that I knew I had. And I remember this voice inside me said, “If you don’t get up now you are going to die.” Something made me get up.

Then they started dragging me to this street that connects to the interior ministry and they took me to this small alleyway that led to the back of the ministry, where their supervising officer, who was in plainclothes and a leather jacket, said to me, “You’re going to be fine now, you’re going to be okay,“ as their hands were still all over my body.

And into this new scenario arrives this older man in military fatigues who says, “Get her out of here.” They took me into an office inside, and the sexual assault ended. But it was just me and the men sitting there. I kept telling them my arms were broken and I needed a doctor. I could tell from the swelling. And they kept saying, “Put your fingers together, you’re fine, see.“ And I’m like, “But it’s my arms that are broken, you morons.”

And then I made a point of telling every single man who came to question me that I had been sexually assaulted. Their reactions were amazing. They’d look away, they’d stammer, they’d ignore me. They’d say things like, “For sure it was crowded.“ And this judge who was there to negotiate terms of a truce with them, said, “Well, what did you expect, you have no ID.” And I’m like, “Because I have no ID I deserve to be violated?“ And he’s like, “How were they to know who you were?” Which is bullshit, because they knew who I was.

YER: Were you scared?

ME: No, I was fed up. But I was seriously concerned that they would charge me with being a spy, because I’m a dual citizen. And I’d lived in Israel, which is extremely unpopular with many Egyptians, and it could have easily created a case by which public sympathy could be on their side.

At one point, some activists came in to try to negotiate a truce, and one of them had a smartphone and I got him to put me on Twitter. I tweeted “beaten and interrogated at interior ministry" and his battery died literally ten seconds later.

Then this general appears — he might have been a famous one, I don’t know — and he turns to me and asks, “Why are you here, my girl?“ I was like, “I don’t know, maybe you can tell me.” I told him, “Look, can you either charge me with something, so that I can know where I stand, or let me go home since I’ve been here for six hours.“ He told me I was going, and then these two military guys appear, and when I ask them where we’re going, they say military intelligence. I refuse to go. I’m a civilian, why should I? Then one of them tells me to stop this Bollywood drama, that I’m going whether I like it or not.

So we get into rickety jeep, every bump I’m feeling in my broken bones, until we get to the military intelligence headquarters by Tiba Mall. It’s freezing and they keep me waiting outside for two hours until the supervising officer finally sends orders to bring me in, where they blindfold me and keep asking me questions like, “You’re Jewish, right?” And I’m like, “My name is Mona Ahmed Eltahawy, where did you get the Jewish from?“ And he’s says, “The file that has come with you from the Interior Ministry is filled with information…”

I mention this because six hours later, they have the nerve to tell me, “Look, Mona, we have no idea why you’re here.“ They were playing good cop, bad cop. Finally some kind of officer walks in, the first thing I ask him is, “Why am I here?” and he says that it’s just a procedure to verify my identity. So we do this whole song and dance about identity again. And he keeps coming and going and disappearing for an hour, and he’d come back and be like, “Look away, look away,“ which was ridiculous since I was wearing a blindfold.

And in the middle of all this, as I’m telling him I was sexually assaulted, all he wants to talk about is the dirt on my hands. “It looks to me like you were throwing Molotov cocktails,” he said. “Look at your hands!“ I told him that the dirt was from when his men were sexually assaulting me.” And he says, “How do we know you’re not a spy?“ Eventually I said, “No more questions. Either let me go or charge me and bring me someone from the American Embassy or a lawyer.” And he pounces: “The American Embassy? Are you ashamed of being an Egyptian? Are you renouncing your nationality?“

I said, “Look, after hours of people of my nationality beating me, sexually assaulting me, ignoring me, refusing me medical attention — after all these things, I want someone here that I can trust. And if that someone is from the American Embassy, I don’t care. I want someone in this room with me that I can trust.”

And then literally in the eleventh hour he comes back in and says, “Okay, you can take off the blindfold now.“ That’s when he tells me, “Look, Mona, we don’t know why you are here.” So who the hell does!?

Then they did this song and dance: “We’re very sorry what happened to you, we’re going to investigate — can you write down what happened?“

Write it down? For the millionth time, my arms are broken!

So, he records my statement with his iPhone, takes pictures, apologizes again, insists that they have no idea why I was sent there — after they had already told me that my “file” is full of incriminating evidence!

The most climactic moment, I think, was when this guy tried to play the elitism card. “The guys who did this to you,“ he said, “you know who they are — they are the dregs of society. We drag them up, we scrub them clean and we open a door in their minds.” He clearly thought I would get mad and say, “Yeah, those barbarians!“ But instead I said to him, “Who made them live like this? And then you’re surprised we had a revolution? And then you ask me why we’re fighting at Mohamed Mahmoud?” I was basically defending the men who had sexually assaulted me against this bastard who thought he could play the class card.

Anyway, so then he gives me fifty pounds and tells me to take a cab and go home. Just hands me an envelope with money and his name and number, “in case I need anything.“

YER: Surreal.

ME: Completely. So I walk out, find a cab — which is playing patriotic music — get to the hotel, pay the cab the whole fifty pounds, since I wanted none of their filthy money. And then a Tweep, Sarah Naguib, takes me to the hospital, and at the hospital — and this is very telling — I’m at the emergency room and I’m telling them I was sexually assaulted and this female nurse says to me, “How can you let them do that to you? Why didn’t you fight them off?”

So this entire night is the microcosm of everything I’ve been talking about. From the nurse who didn’t think I fought them off hard enough, to these good cop/bad cop guys, to them telling me that my sexual assault was by the animals of Egyptian society — which they have created, you know. That whole night, it changed my life.

YER: In what way?

ME: In the way that it brought me to where I am now, being a writer with casts on both hands, only being able to use a touchpad with one finger. It took the fight that I used to use my words for to my body. My body became the source of my activism. Whether it’s me appearing on TV and talking about what happened, or my hair, or my tattoos.

YER: So the hot pink hair is post-assault?

ME: Oh yes. When my arms were broken I vowed that when I physically healed — because emotionally I haven’t — I would celebrate my survival by dying my hair red. For me red is a very defiant color. And in the same way that I now go back to Egypt every month to tell the authorities they can’t keep me away, the hair also says, “I am here.“

Don’t you love it? People tweet me at airports to say they saw me — you can’t miss the red!

YER: And the tattoos?

ME: The tattoos just came to my head. Look [holds out forearm], this is Sekhmet. I was on a speaking tour in Italy, at this museum in Turin where there are many of our national treasures that we supposedly sold to some rich Italian man two centuries ago. And we’re in this room, and the director of the museum says, “And this is the ancient Egyptian goddess Sekhmet — we have nineteen of her statues in this room, and she is the goddess of retribution and sex.” And I thought, “Oh! I want that! Retribution and sex!“ I was like, “Sekhmet is my woman.” So I decided on Sekhmet here, to celebrate my ancient Egyptian heritage. And on the other arm, I’m going to get Arabic calligraphy of Mohamed Mahmoud and Horreya, to celebrate the street, and the Arabic script.

YER: So the tattoo is also post-accident?

ME: In August! I went red, and then went straight to the tattoo artist. This is Sekhmet à la Molly Crabapple, an artist friend who designed it. Sekhmet has the head of a lioness and the serpent on top and all that, and she looks like a hieroglyph, obviously. And her dress is usually red, and the color red is generally associated with her because she’s associated with blood and war. According the legend, when humans turned against her father, the sun god Ra, she went on a rampage. And to stop her, the priestesses created this concoction that was a mix of wine and possibly opium and other things, and they poured it on the ground ahead of wherever she was about to go. And when she arrived they said, “Look, Sekhmet, you’ve killed everyone already, the blood is here on the ground.“ So this concoction calms her down, calms her bloodlust, and then they have an orgy to celebrate.

YER: So you have bloodlust?

ME: [Laughs] Well, the reason for the tattoo is because of the boys who wrote their mothers’ numbers on their arms at Mohamed Mahmoud. Sekhmet is my mother in that kind of symbolical way.

I didn’t choose this scar [_points to her hand)], I’m very proud of this scar, but they left this mark on me. I wanted to put markings on my body that I did choose, that celebrate my survival.

Last summer I lost this suitcase that totally tore me up. I had a breakdown over losing it. It had a lot of Azza Fahmy jewelry that I’d been collecting for a very long time and that was very dear to me and that I’d wanted to give to my sisters and nieces when I died. And a lot of clothes… things that were really dear to me. It got lost in transit somewhere.

I had a breakdown over this in Cairo and I realized that it was a displaced kind of trauma. I don’t know what I lost when they attacked me last year — but any kind of attack like that, you lose something. You just don’t know what it is. So I was like, “You know what, no one can ever take my tattoo away from me — this can never get lost.” It was a way of figuring out what I can and can’t lose, changing myself in a very obvious physical way, and emotionally, too — though I don’t know where I’m going to end up. I’m trying to have this out in a very public way, through Twitter. I tell people all of this, and I want to write an essay about it. A lot of my detractors will say it’s for narcissism and self-promotion. They’re entitled to their opinions. But I’m doing it for a reason — I think that we don’t talk about trauma enough, we don’t talk about vulnerability enough. When I am in to Egypt, everyone I know is traumatized. They’re not able to put it into words. So I’m trying to go through my trauma — very publicly — as a way for those who can’t have that very public discussion to watch it happen. Perhaps to recognize the relationship between strength and vulnerability. I’m hoping that it will help someone.

YER: Hearing you, I wonder if the anger toward your piece — which as you know I was angry about, too! — was actually discomfort at issues that many women in the region face but are unable to speak about? That you are able to be so vocal about things that women are made to feel ashamed of.

ME: We’ve been told to be silent about it. Twelve other women were sexually assaulted. You know the organization Nazra? They contacted me and they said, “Will you join this lawsuit with us?“ and I said, “Of course.” And they said to me, twelve other women have gone through what you’ve gone through, but none of them want to pursue it. They can’t, for whatever reason.

YER: But you can?

ME: I’m older, I’m forty-five. I’m not a virgin. I was married, I talk about sex openly. I’m a public figure. They can try to shame me, but it’s almost like I’m beyond shame. So for all of these reasons I’m obliged to talk about this stuff in a way that a twenty-six-year-old Egyptian virgin can’t. And I’m not speaking for her! I’m speaking about my experience, but in so doing I hope I can help others say, “This is what happened to me.“

Blue bra girl — and I hate that term and I never use it — she’s been silenced by her family. They won’t let her speak. It’s outrageous, Yasmine! They might as well just put tape over our mouths! And then they get angry that I wrote an essay in Foreign Policy?

YER: What about—

ME: Wait, let me tell you where the men’s rage comes in, because a lot of men wrote to me after what happened, and their reaction was this:

Dear Sister Mona,

I’m so sorry about what happened to you. I want to bow down before you and kiss your feet because I was not able to protect you. But I vow to you, that I will not rest until I avenge your honor.

So I think this is very interesting. I write back and I say:

Dear Brother So-And-So, I am so grateful for your support.

Thank you. I am very moved.

But.

My honor is intact. Nothing has happened to my honor.

And let’s vow together to restore Egypt’s honor. Men and women together, because that’s how our revolution will succeed.

Sister Mona

The regime does these things to us because they know it emasculates our men. Our bodies are the battlefield, the nexus of power and sexuality. So the regime does this and our men — even men very close to me, including men I’m emotionally involved with — feel emasculated, and they want to go back and take revenge. Or, because I was on the front lines and they weren’t, they feel emasculated in that way. I’m like, I’m not responsible for your masculinity issues. I’ve got enough to deal with!

But that nexus of power and sexuality is the revolution that I want to fight. Which is why I’m going back to Egypt. We weren’t ready for that in the eighteen days. Now that more and more people see what I wrote about in my essay because they go to the protests and they get groped by the very men who were keeping the physical revolution alive against the police, we can start talking about this revolution. Why are these young men who are so courageous groping me as they are running away from bullets?

And this is where I enter now and say: because the revolution is happening over our bodies. And unless that nexus of power and sexuality is reckoned with, there is no future. That’s what I want to do in Egypt — I want to work against sexual violence. There are so many people on the ground working on this, but they’re just not working horizontally. If we put all the different initiatives under one umbrella, we can have a national campaign. I’m going to be working with the group Baheyya and their community of artists, writers, musicians, going into the rural areas we normally never see, reaching out to people. Working holistically, with doctors, creating female police units in precincts, getting rape kits and crisis lines and free therapy in place. Working with the Ultras to get awareness down to the streets. Working with football stars like Abu Treika to make a billboard that says, REAL MEN DON’T GROPE.

It’s going to take years, but I’m totally fired up about it. So this will be the activist part of what I do in Egypt, where — again — my body becomes a tool. I never called myself an activist before now, but after Mohamed Mahmoud, I’ve become an activist, as a kind of therapy.

YER: When we first corresponded you replied to my email by apologizing for the tardy reply because you had been busy responding to hate mail.

ME: Every single day! I read it all, I respond to lots. But sometimes when I begin to read it and it’s like, “You cunt, you bitch,” I realize there’s no point.

YER: It doesn’t upset you?

ME: When it comes from the right wing, I expect it. When it comes from what should be allies on the left, that hurts more.

YER: I notice that some of the people on Twitter who I know used to hate you, despise you even, are now flirting with you on Twitter.

ME: I know! It took a few months, but I think people have come around, especially as more and more women face the kind of assault I did. And I’m glad people are coming around — we need to move beyond that knee-jerk position.

YER: I don’t see the Muslim Brotherhood being too thrilled about your return.

ME: It’s true, but I plan to make a very public appeal to Morsi, to say, “Look, you claim to be the president of all Egyptians, you could have really helped things when you were in Tahrir opening your jacket saying, ‘Look look, no bulletproof vest.’" He could have said something about the price Egyptian women have paid.

YER: How did you feel about Morsi’s win and that speech in Tahrir?

ME: I was much more depressed than I expected. I think we have five or ten years of really hard work on the ground to get to the point where we can get rid of what the military dictatorship of the past sixty years created and begin to build the country we hope for. If we don’t look ahead, the revolution will die. And we have to be optimistic. Our optimism is our biggest weapon. If there’s no optimism, forget it — pack the whole thing in. I think Morsi is an ineffectual, utterly unprepared nobody. He was just a fill-in, like a spare tire. The problem with him is he’s a soft cuddly grandpa, uncle-looking guy, which made a lot of people say, “He’s kind, give him a chance.“ That’s crap.

YER: What’s your take on the Brotherhood?

ME: They’re too ingrained in collective thinking. It’s not rocket science — the Muslim Brotherhood is a microcosm of the regime. The Supreme Guide is Mubarak. A topdown structure, just as the country had when Egyptians said no. So they need an internal revolution.

But they’re organized! They’re out there doing things, and all we can think of is Tahrir. The extent of our political imagination is, “Let’s go to Tahrir!” I love Tahrir and wish I were there right now, but for God’s sake, people.

YER: What about Brotherhood defectors, like Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh?

ME: [Shudders] Who are you? You told every political faction that you were what they wanted. To the left you were a leftist. To the Islamists, an Islamist. You represent nothing man, nothing. Not a fan. Don’t buy the soft, cuddly, Islamist guy.

YER: So are you categorically anti-Islamist?

ME: No. I have a platform, and it’s more than being anti-Islamist. My platform is to create a ceiling of freedom that is high enough in Egypt that it encompasses everyone’s freedoms. What last year has done for me is that it has moved me beyond reacting to their agenda. With my essay, with my arrest, with the kind of stuff I want to do now, I’m creating an agenda that other people have to react to. Now, whenever anyone writes something about women’s rights in the Middle East, they always mention my Foreign Policy piece. It has put a flag on the ground that you have to respond to. And that, for me, is taking away from them. In the past it was their flag people had to respond to. Now it’s mine.