I met Naguib Mahfouz for the first and only time at a secret location in Cairo. This was after October 15, 1994, the day he was attacked in one of the alleyways he frequented on his daily walk, by a stranger who stabbed him repeatedly in the neck. The story goes that Mahfouz took himself to the hospital and waited his turn, pressing his hand — the same hand with which he had, by this time, written over forty novels, a couple of memoirs, and several hundred articles — against the open gash in the side of his neck, telling the nurse, in his characteristically soft voice, at once informal and given to conviviality, “It’s nothing serious,” before revealing to her the fountain of blood.

Before that day, Mahfouz’s regimen had been famously predictable: the streets he walked, where everyone knew him and knew not to interrupt, the cafés where he was a regular. Now his movements were circumscribed. This was due as much to concerns for his safety as it was to his waning health: old age had been violently advanced by the assault. He almost never walked alone in public. He met friends at an undisclosed venue for their weekly salons.

An acquaintance procured an invitation for me and my wife, the photographer Diana Matar. The hotel was out of the way and unremarkable, on the Maadi stretch of the Nile Corniche, facing the water. The instructions we had were to announce ourselves at reception and say that we were there for the Mahfouz soirée. But the man behind the desk was skeptical.

“Mahfouz? What Mahfouz? And I don’t know what you mean by ‘a soirée.’”

He wrote down our names and went off. After a few minutes the man returned and now, with an entirely changed manner, led us to an elevator. When the doors pulled shut, he blushed a little and said, facing the floor, “Welcome. You have honored us.” We got out at the fourteenth floor and followed him to the end of a long corridor. He knocked at the last door, opened it a few inches, and announced our names.

The room was a large, cleared-out suite that had been haphazardly furnished with sofas and armchairs clustered in the middle. The curtains were drawn. Mahfouz, dressed in a dark olive safari suit, stood up and, aided by his assistant on one side and a wooden crook-handled cane on the other, walked over to us. The ten or so people gathered there also rose. Mahfouz’s assistant shouted into his ear, “Mr. Hisham Matar. A Libyan writer. And his American wife, Madame Diana.”

Mahfouz slung his cane on the inside of his elbow and extended both hands to me. His skin was cool and soft. He smiled and whispered a one-word question, “Libyan?”

“Yes,” I said, nodding in case I wasn’t speaking loudly enough.

“With or against?” he asked slowly.

“Against,” I said.

“Excellent,” he said. “Come sit beside me.”

Much was said that evening, and the comic theme persisted, whereby Mahfouz, the only one who was hard of hearing, continued to speak in a near-whisper, while everyone else had to shout. It was a demonstration of the age-old fact that anything, no matter how beautiful or profound, inevitably sounds empty when said at a high volume.

“How many more do I have left?” he suddenly asked his assistant.

“Three,” the man yelled.

Mahfouz seemed relieved. He lit a cigarette and smoked it with great relish, each exhalation producing a cloud of smoke that floated whitely above him. Half an hour later, he asked the same question. “Two!” came the answer.

“He is only allowed five a day,” the man beside me, a philosophy professor, explained. “Doctor’s orders.”

The gathering was made up of local writers, critics, and academics. They shouted erudite questions and bits of literary news. Mahfouz listened modestly, his vein-webbed hands resting on his knees, facing forward, his back not quite touching the sofa, as though careful to take up as little room as possible. It seemed that at any moment he might get up and leave. Nearly every time that he was asked a question, there was a pause before he spoke. We would sit there, waiting for him, watching him stare ahead. Sometimes, he said nothing, holding the silence until someone got up the nerve to say something, often attempting to speak on his behalf, which made the silence that followed weightier than the first.

Asked whether he believed criticism can help a writer, he said, “Of course.”

“Would you then say you learned from those who have written about your work?”

“Of course,” he said again.

When it was my turn to speak, and although I had nothing to say, I leaned close to him, taking note of his large ear. Anyone looking at us would think I was about to confide a highly intimate detail about my life. But my volume had to be at broadcasting levels.

And no sooner did I ask my question than I regretted it. “How do you see writers such as myself?” I shouted. “Arabs who, having grown up inside another language — in my case, the English language — have come to write in it?”

I was young, still in my late twenties, and such questions preoccupied me back then.

For once, Mahfouz replied quickly. “You belong to the language you write in.”

A silence filled the air.

Then, perhaps to console me, he added, “But who cares? Does it matter what language Shakespeare wrote in?”

Whenever I have told this story — and I have told it some dozen times in the quarter of a century since — I often catch myself adding, for reasons I am yet to fully understand, words that Mahfouz did not speak. They are words that I have never heard anyone except myself speak, words that I attributed to Mahfouz, perhaps using him as a cover to add poignancy to thoughts I have always secretly believed and which, sitting beside him that day in Cairo, I felt I understood better than ever before: “Every language is its own river, with its own terrain and ecology, its own banks and tides, its own sources and tributaries and destinations where it empties, and therefore every writer who writes in that language must swim in its river.” Every time I “quoted” him saying this, my listener would nod in agreement and together we would take a moment to share our appreciation for Mahfouz’s words, which, of course, weren’t his at all, or at least not ones I had ever heard him say nor encountered in any of his books — they were, as the expression goes, words I had put into his mouth — and, out of the shame and perplexity that this almost always induced in me, I would press on and tell my companion that, although those words had been painful to hear, they communicated a complex truth, one for which I remain grateful.

That encounter with Mahfouz, like a lucid and useful dream, helped reveal something I already knew but had been unable or unwilling to acknowledge. As with all our recountings of dreams and stories, we are engaged in a creative act, selecting what to emphasize and what to leave out, sometimes adding in new bits. We make of them what we need and reveal a great deal about ourselves through them. Despite the social risk of boring others, our dreams and stories contain the most intimate details of our psyche. Whether we understand them or not, they divulge the temperament of our innermost self, the self that, at night or in our imagination, breaks free from the clasp of our conscious will.

After his stabbing in 1994, the world of dream became ever more significant for Mahfouz. For the next dozen years, until his death in 2006, he wrote them down, capturing each one in a few swift strokes. Not only did he trust his subconscious, he trusted us with it, publishing a first collection of them in 2004 under the title Dreams During a Period of Convalescence. A second volume appeared posthumously as The Last Dreams. And it is that volume that has fascinated me, not only because it contains some of Mahfouz’s last writings, but also because translating these dreams felt like the most natural thing in the world, as though I were stepping into their tide and all I had to do was let go. One Sunday morning, as I drank my coffee at the kitchen table, I thought I might translate a couple of entries for Diana and then, by the time she was up, I had completed a dozen.

Mahfouz’s dreams are an insight into the writer’s twilight concerns. They reflect the concerns of an old man, regretful about missed opportunities, melancholy about the future. At times we arrive with him at the shores of the morning, when he wakes up fatigued and confused from a dream of amorous dancing, or when he reads in the morning paper the obituary of his old lover B, of whom he had just been dreaming. Several of these dreams — dreamt seven or more years before Tahrir Square and the Arab Spring — seem oddly prophetic in their depiction of national unrest and unfulfilled democratic yearnings. Asked once what subject was closest to his heart, Mahfouz replied: “Freedom. Freedom from colonization, freedom from the absolute rule of a king, basic human freedom in the context of society and the family.”

Almost every dream begins with “I saw myself” or “I found myself.” In Mahfouz’s dreams, we are often unsure about the references or their import: we are very much inside a private world. And yet we cannot help but detect patterns and themes: the insistence of hope in the worst of times; the failure of politics; the dream of democracy; love lost; mismatched yearnings. The entries are brisk and brief, as though he were catching clouds or rescuing a fading image from oblivion. It is clear that Mahfouz, the professed realist, coveted dreams for their agile and wandering narratives, their often unsettling psychological and emotional power, their economy: how, in an instant, a convincingly compelling world, no matter how unlikely or strange, is evoked. The cumulative effect is a canvas of intimate communications, and yet, because Mahfouz has astutely refrained from any commentary or interpretation, the dreams are as formal as they are intimate. It is a contradiction that hums through them.

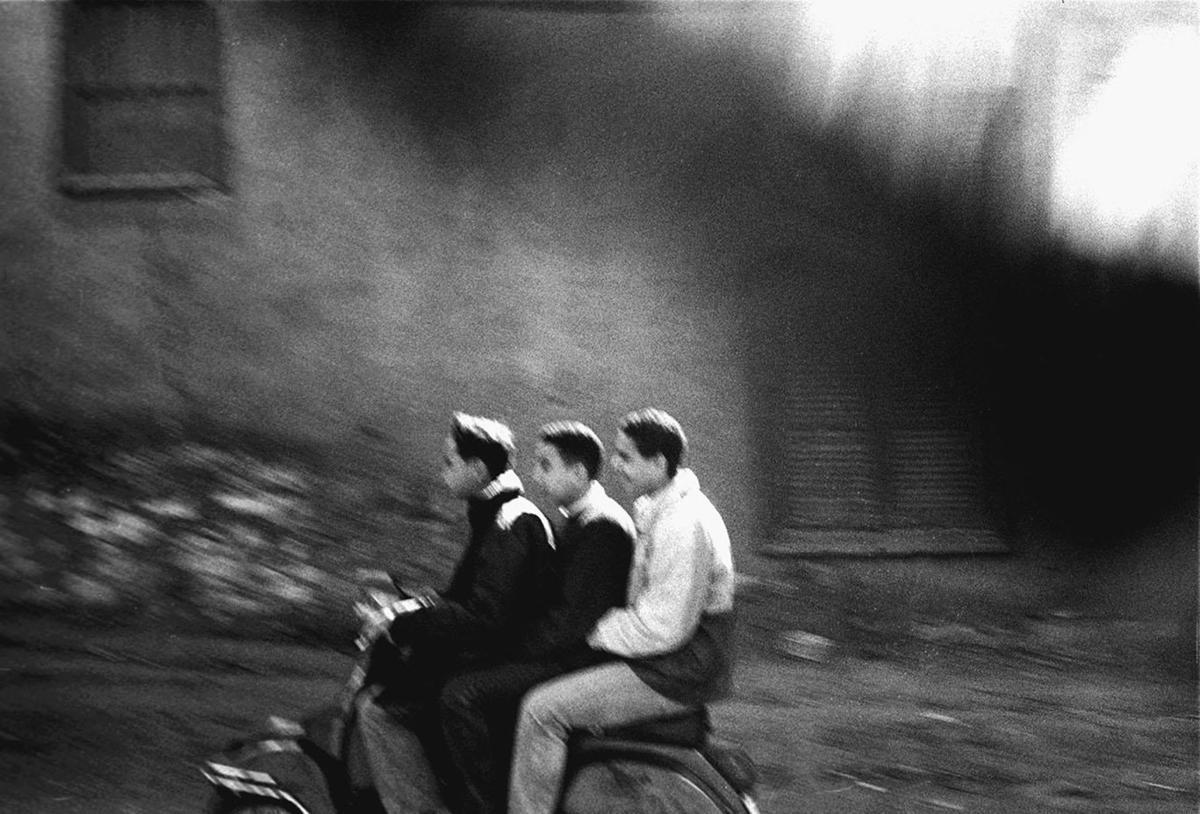

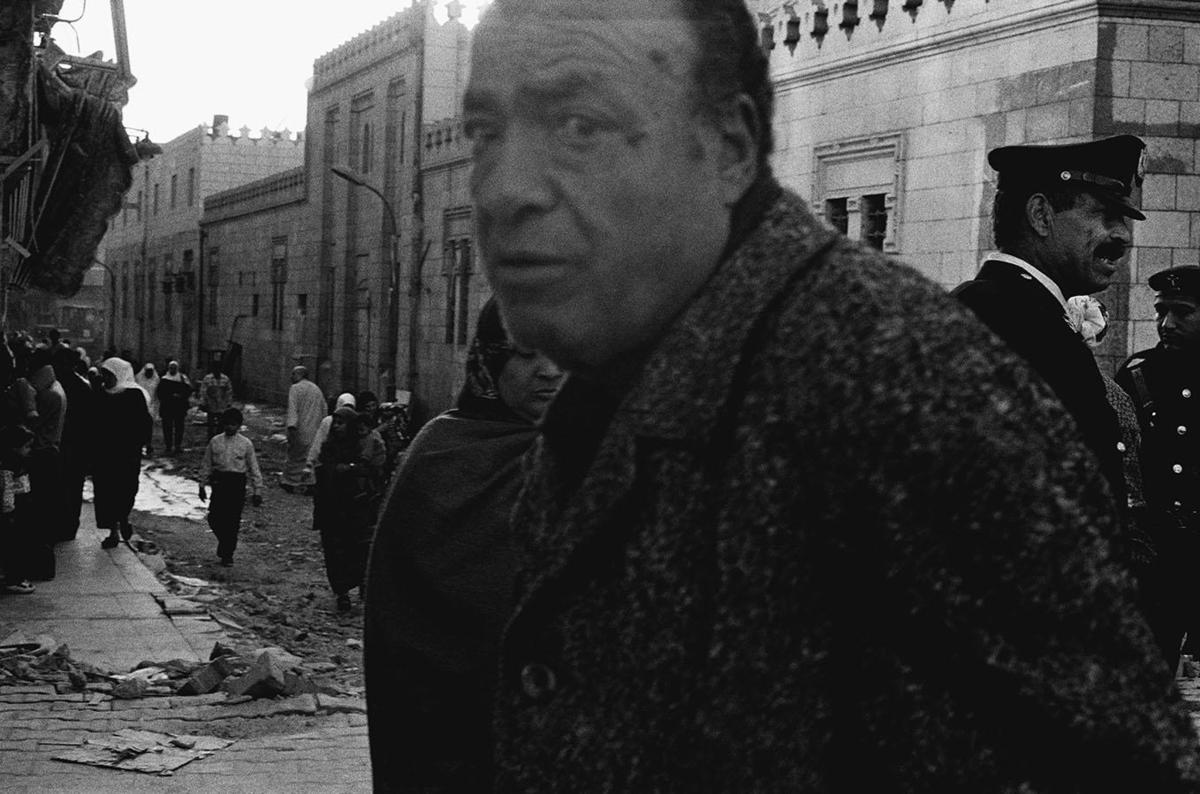

By the summer we met Naguib Mahfouz, Cairo was already the focus of Diana’s artistic practice. She had become fascinated by the city some three years earlier, and it would continue to serve as her muse for another four years. During that time, she would periodically travel there, spending days and nights wandering the streets alone with a camera. The images she captured are vivid, haunting, oddly mobile and uncertain; very much like a dream. Looking at them today, they appear, like Mahfouz’s dreams, as intimate evocations of the city: the unwitnessed moment, the passing faces, so many places and instances that seem constantly at risk of vanishing. As with Mahfouz’s dreams, there is a tender caution in Diana’s images concerning the prospects of an unknown future. A dialogue between two artists — one using words, the other photographs — both standing at the border of the night.

— Hisham Matar

I found myself in a strange and sad place when suddenly my old love, B, appeared. She walked burdened by old age. Knowing that I will never see her again, I felt such deep sorrow.

I saw myself in my forties, caressing a pale rose. It responded, encouraging me, but, given our age difference, I hesitated. My reluctance persisted until she left, leaving me alone to contend with my aging self.

I saw myself studying law in order to please my father. For comfort, I secretly disappeared into song. And finally, when a choice had to be made, I grew tormented. But my spirit won out in the end.

I found myself in a spacious and elegant hall. Gathered to one side were my family and friends and, at the opposite end, a door opened and through it my sweetheart, B, entered laughing, followed by her father. I lost all self-restraint and opened my arms wide. The imam began writing in the marriage book. Joy overtook everyone. My mother congratulated the bride and burned incense.

I found myself walking down a long road. A window opened to my left and through it appeared a woman’s face. Although her beauty had disappeared behind a thick veil of ill health, and it had been fifty years since I had last seen her, I immediately recognized her. In the morning, I was deeply unsettled when, reading the newspaper, I came upon her obituary. I was profoundly saddened and wondered which of us had visited the other at that hour of death?

I found myself in my study. Mrs. S came to say goodbye before immigrating to another Arab county for work. She placed her hand in mine, and kept it there as her green eyes filled with tears.

I found myself sitting with President Jamal Abdel Nasser in a small garden. He said, You may be asking why we don’t meet as often anymore. I said, I did wonder about that. He said, It’s because every time I consult you about an issue, I find that your opinion either partly or entirely contradicts mine, and so I feared for our friendship. I replied, For me, our friendship — no matter our differences — can never end.

I found myself at Café El Fishawi. A short distance away was the famous artist and ballerina soon to announce her retirement. I couldn’t help looking at her with great curiosity. She gracefully turned around and her lips gave me a faint smile. My companion said, Be glad, you won’t embark on life’s final battle alone.

I found myself facing a stage on which the leader Saad Zaghloul was sitting beside Mother Egypt. Suddenly a man approached, claiming to be the lady’s true husband and asking her to follow him. He presented his papers but the leader waved him away and said, We will let the law and the people decide.

I saw myself among a group of young contemporaries. I noticed that one of them was neurotic and unstable. A young woman treated him with kind affection and he recovered his mental well-being. A deep love grew between them but then his companions wanted to test him: They suggested I pretend to be the woman’s lover. I did, and she politely rejected me. But then it was as if I truly loved her. It hurt that she preferred the other man who’d been unwell. Then, from far off, we heard the kind of music used to cure those possessed by demons. The woman began dancing, and I danced with her until I woke up, exhausted on the shores of a new day.

I found myself visiting my mother in our old house in El Abbassiya. She received me with perplexing indifference and then left the room. I assumed she’d gone to make coffee but she never returned.

I found myself at a police station, representing the residents of my street. Given the sharp increase in robberies, I asked the chief constable to assign a police officer to patrol our street at night. He said he had done that for another street and when night had fallen the thieves had killed the officer. I asked if we could be permitted to carry arms to defend ourselves. He said that would make of us an even greater threat than the robbers. In that case, I asked, What do you suggest? He said, Keep the streetlights on and shut all your windows and doors.

I saw myself with her in the tea garden, where she was saying, You promised to visit my father and so my family have been expecting you. I told her that ever since I had discovered that I was twenty years her senior, I’d grown reluctant, convinced that the marriage would be unfair to her. She said: But I don’t mind. And I said: I don’t want to be unjust or to abuse your innocence. Horrible, long, dark days passed before I learned that she’d married my colleague, A. N. He and I were contemporaries and, what’s more, he was a widower with a daughter old enough to get married herself. I remembered the poet who said:

He who listens to gossip will die of grief

While he who follows his desire is bold in his belief.

I saw myself sitting with the late K on the balcony of his country house under the bright light of a full moon glowing in the deep heart of a rural night. He said, You know that I don’t care much about politics, but despite that, the dawn patrol descended on me, blindfolded and dragged me to a dark cell where I spent a month without being charged or told the reason for my arrest. When I returned to my village, my nerves were shot, and that’s how I met my end. I said, All the rabble walked in your funeral, speculating.

I found myself in the Al Ghouriya district, where there were twice as many police as civilians. I saw my father walking toward me with a policeman on either side of him. I panicked, thinking he was under arrest. But then he greeted me and said, I see a policeman on either side of you, and I’m afraid you’ve been arrested.

I found myself in a group of young men listening to Osman Bouzi, the most prominent producer of perfumes during my youth. He was calling on us to boycott foreign goods. My father told me, sitting cross-legged on his prayer rug, That’s all very well, but we haven’t yet manufactured the most essential products. I told him, Well, let’s start with what is possible.

I saw myself receiving a precious gift from the hand of the artist who was also a spiritual sheikh, and he said, You cannot enjoy it till you reach the place where the Nile meets the sea. I went there and found him waiting for me. We enjoyed the gift together. Our throats rang with sweet melodies until the blessed dawn call-to-prayer swam across the early moist air.

Naguib Mahfouz (1911–2006) won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1988.

Hisham Matar is the author, most recently, of the novel My Friends (2024). His memoir, The Return: Fathers, Sons, and the Land in Between, won the Pulitzer Prize for biography in 2017.

Diana Matar is an artist and photographer. Her most recent project, My America (2024), charts a geography of police violence in the United States through photographs of the official addresses where killings transpired.

Adapted from I Found Myself… The Last Dreams by Naguib Mahfouz (2025, New Directions)