Larry Gagosian is the kind of person about whom everybody has an opinion, though little is actually known. Rumors swirl around him like wind on a djinn. He only dates tall black women. He’s secretly a Rosicrucian. He is a great friend to widows and children. He was married once for five minutes. He drives a Ferrari. He was friendly with Kurt Vonnegut. He loved Leo Castelli, and vice versa. He has the personality of a swordfish. (This last, courtesy of an interviewer in the Financial Times.)

Until recently, at least, he was loath to give interviews.

We know a few things. Gagosian is sixty-seven years old, the son of Armenian émigrés: a housewife who was once a minor actress (she appeared in an Orson Welles production) and an accountant who worked for the city of Los Angeles. He loved — loves — jazz. He majored in English literature at UCLA, did a brief stint at the William Morris Agency, made some money parking cars. Not long after, he started selling posters on the street for extra cash — and not long after, never looked back.

He might well be the most powerful man in the art world. Certainly the unabashedly commercial, supersize art world that we live and work in today owes much to Gagosian. He was one of the first to make his galleries more like museums, the better to present big, museum-quality shows (like a memorable 1988 exhibition featuring Roy Lichtenstein’s tongue-in-cheek Picasso paintings, or another, in 2009, of late Picasso). He is famous for his eye, and for his shrewdness. His artists have included Andy Warhol (Gagosian is credited with creating the posthumous market for Warhol), Jean-Michel Basquiat, Jeff Koons, Cy Twombly, and Mike Kelley. He has surrounded himself with enviable specialists — scholars like Robert Pincus-Witten and John Richardson, brainy aesthetes like the late Robert Shapazian. And his market prowess is undeniable: In 2006, he brokered the sale of Willem de Kooning’s “Woman III” (which had made its way out of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art in circuitous, film-worthy fashion) for $137.5 million, the highest price to date for any painting. The critic Peter Schjeldahl has said of him, “He’s like a shark or a cat or some other perfectly designed biological mechanism.”

Today there are twelve Gagosian galleries, from Beverly Hills to London to Hong Kong. The latest, in Paris, sits in a 1950s airplane hangar; access appears to be reserved for the .0001% who own private jets.

In early November of last year — it was Election Day — I met Gagosian at his mostly white offices at 980 Madison Avenue in New York City. Having arrived early, I was told to take a long walk, and made my way around an exhibition of Twombly photographs — sweet things, faded and nostalgic — along with a suite of his late paintings — bright and huge and lush, almost vaginal, bursting with life. After some minutes of lolling about as collectors strolled by and the gallery’s security guards timed their smiles accordingly, I was ushered into a hallway and then another hallway stuffed with two pretty young assistants and finally to his office. A mottled Lucio Fontana canvas hung on the wall. I sat beside a well-heeled member of Gagosian’s public relations team (she insisted on supplementing my recording device with her own). Having expected someone with the attention span of a gnat, I was somewhat rattled by how friendly and focused he was.

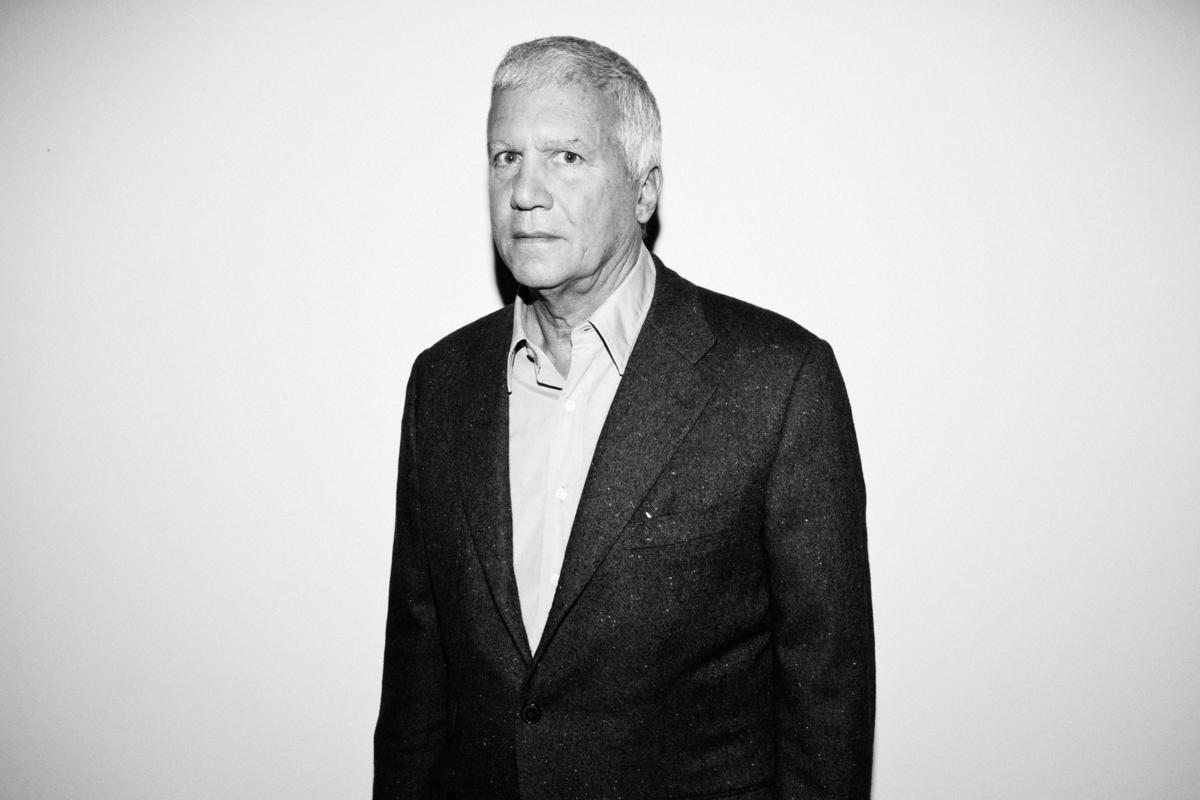

Gagosian is at least six feet tall with closely cut gray hair and steel blue eyes. The emperor’s suits are probably… expensive. He is laconic, and boasts a gratuitously everyman manner that may or may not be disingenuous but which seems charming for a man whose biographies have yet to be written. His primary mode is sanguine self-assurance undercut by occasional (but vivid) impatience. For the whole of some forty-five minutes, he trained the formidable ammunition of his eyes on me, only occasionally rebuking me for my muffled delivery.

Negar Azimi: We share Robert Shapazian in common. He and I became close back in 2000 or 2001 and traveled around together a bit. I had been in Cairo working with the photographer Van Leo, and Robert was so interested in photography, as you know. Bidoun actually did an interview with him in our first Interview issue eight years ago (Anna Boghiguian and Robert Shapazian in Bidoun #8).

Larry Gagosian: Did you ever go to Africa with him?

NA: I did. We went to Mali for the photography biennial in Bamako. And he came to visit me in Cairo. He was the first person I knew to use antiseptic hand cream…

LG: He was germ-phobic.

NA: Totally. He was particular. We would go to expensive restaurants and he would order fruit salad and then pick at it… [Laughter] How did you two meet?

LG: I’m pretty sure I met him here at the gallery on Madison Avenue. He came to my attention as a collector of Duchamp and Warhol, and we’d always been involved with Warhol. I think I sold him some paintings. But we didn’t really become close friends, I was just aware of his collection and his ambition as a collector. At a certain point we had a mutual friend, Daniel Wolf, who was really close to Robert and was involved in photography — as you probably know, he had a great photography collection. He knew I was working on this gallery in LA and I hadn’t really settled on a staff or director, and Daniel suggested that Shapazian would be a good guy to talk to. I was a little surprised because I’d always thought of him as kind of a well-to-do, not terribly… employable collector. But Daniel put us together and Robert warmed to the challenge of the gallery and we ended up having a long association. He worked for the gallery for ten years or longer, I can’t remember exactly. A significant period of time.

NA: He had a super-ironic and wry sense of humor.

LG: Yeah, he was hilarious. Very funny. And really smart. He was terrific. It was great to have such an eccentric, brilliant guy in the gallery.

NA: I have to say, Robert being of Armenian origin… I have a lot of interesting Armenians in my life, and it’s left me thinking that there’s something really peculiar about your diaspora—

LG: My what?

NA: Your diaspora. I know that you supported Arshile Gorky, for example.

LG: Well, we’ve done several Gorky shows. We’ve been the primary gallery for the Gorky family for many years and — yeah, as an Armenian American, I was understandably very proud of Gorky, one of the great artists of the twentieth century, one of the pioneer abstract expressionists, who happened to be Armenian. He had a very sad personal story in many respects — with his immediate family and then, you know, the genocide in Armenia, which took his mother and many of his relatives. He had kind of a sad life as an artist; I mean, he ended up dying of cancer after his studio burned to the ground, and his wife left him… which is kind of understandable, because it really kind of fell apart for him. He was a great artist with a very moving personal story.

NA: I heard that you and Cy Twombly had talked about possibly going to Armenia together at some point.

LG: We did. Very sadly that didn’t happen. But Cy had a particular connection to Gorky, who lived in Virginia on and off. Cy did a drawing — I wish I owned it — there was a wonderful drawing I think from the 1980s where he wrote on it “My people eat stones" or something like that, and it was a direct reference to the Armenian genocide. I don’t know who said it, originally — it might have very well been Gorky who uttered that phrase. Cy was born in Virginia, as you know, he had a studio there, and the Shenandoah mountains… there was a series of works on paper and paintings by Gorky called “Virginia Landscapes.” So there was this kind of connection from different points. And there was the work Gorky did, particularly his mature work, starting in ’42 to when he died — you can see that Cy must have been influenced in some ways by a certain freedom in Gorky’s work. There was kind of a break with European art, which would come to be one of the foundations of abstract expressionism.

NA: But his life ended so quickly.

LG: He was a young man in 1948 when he hanged himself. And if you look at the other abstract expressionists — Rothko hadn’t made any of his signature paintings, Franz Kline hadn’t made one yet, Barnett Newman had just begun tentatively… so if you look at it that way, it’s very interesting. Pollock had just started to do the very first drip… Gorky finished when they were just starting, so it’s kind of an interesting timeline, the timeline’s very interesting. I’m sure if he’d lived longer, if he hadn’t had such a tragic death, he undoubtedly would’ve gone on to do many more great works.

NA: Cy also had a relationship to the Middle East that was kind of special.

LG: What?

NA: Cy Twombly also had an interest in the Middle East —

LG: Yeah, he was a traveler. Cy used to travel a lot in the Middle East in the Fifties and Sixties.

NA: To Iran.

LG: Afghanistan, Iran. He used to romanticize that part of the world. But then there were the changes that took place and it became more difficult to travel there…

NA: And less free.

LG: It became less safe. There was freedom of travel, you know. I think a lot of people enjoyed travel in that part of the world in a way that you can’t really now.

NA: People used to drive!

LG: They used to get in a car and drive to Damascus. It’s hard to imagine now, when you look at the news and you see what’s going on. Regardless of how you view the Arab Spring. Certainly it’s become a more complicated part of the world.

NA: I was in Abu Dhabi the first year or second year of their art fair where you gave a talk. You were very frank about your professional history and how you got to where you are. Could you tell me a bit about that moment? When you started out. What was your visual world like at that time? I mean, were you interested in visual culture at all?

LG: To be honest with you, I wasn’t really interested in art. I had never thought about having a career in art and didn’t really understand the art world or… I was an English major in college. It was really kind of a fluke. I started selling posters because I thought I could make more money that way than parking cars. Simple as that. I saw somebody else selling posters and I basically just copied their business. It was a total lack of imagination. Of direction, really. It was just like, I could sell posters instead of just parking cars, so I was parking cars and selling posters and making more money and it just led me to a kind of wonderful life as an art dealer. There wasn’t a plan to get into the art world; I didn’t see this as an entry point. It was not a professional decision — if I’d seen somebody else selling something, I might’ve sold that. I was very lucky that it turned out to be a career path.

NA: What were those first posters you sold like? Did you try to psychologize what people liked to put on their walls?

LG: What?

NA: Did you think about what people might like to put on their walls? There must have been a fair amount of psychology—

LG: Not selling posters. It was just like, get them to buy it. You know — ask for twenty dollars and be prepared to take anything north of ten. It was a street business. It wasn’t about psychology.

NA: But were they reproductions of canonical works of art?

LG: They were not reproductions of works of art. They were really what we call schlock. Cheap posters of bad paintings. I mean, it was not what you’d find in the poster shop at the Whitney or the MoMA. You would buy the poster for fifty cents. It wasn’t really a poster, it was a cheap print.

NA: That you framed.

LG: That you put a frame on. You buy the print for about a dollar, the frame would cost you two, three dollars, and then you try to sell it and make a profit. And I’d make a couple hundred bucks a night, which was a lot of money.

NA: And were you selling to college students or —

LG: Anybody who walked by. Young people… I mean, somebody who wants something they thought was attractive to put on their wall and they don’t have a lot of money. People have to hang something on the wall, I guess, so this was kind of the bottom of the barrel. [Laughs]

NA: Right. I mean, we always joke that the Iranian diaspora in LA — they all have posters of Van Gogh’s flowers, like some —

LG: No, no, don’t make any cultural connections.

NA: Okay. Not at all?

LG: It was just something to sell. And then I started buying more expensive posters, because the company I bought my posters from made posters that would cost me, instead of a dollar, maybe twenty-five dollars, fifty dollars. So then I could put a better frame on it and sell it for a couple hundred bucks, and I’d make money faster that way. And that slowly got me looking at art as… You know, I wasn’t really that much into art. I sort of liked it. But I was really captivated by writing and poetry and music, that’s really what —

NA: That was your world.

LG: Kind of. Those were my friends. We didn’t talk about art, we talked about writers. We talked about musicians. But once I got into it, it really kind of took over; it pulled me in a very strong way. And I enjoyed making a decent living. I didn’t grow up with money, so it was nice to be able to buy things and get a better place to live, you know, all the things that come along with a certain amount of success. And that was very seductive. So it was two things: for the first time I’m actually making money. I was on my own, I was thirty years old, and then when I had my first gallery I was like thirty-three, thirty-four, but it was the first time I ever had any money and that was exciting, to be honest with you, to be able to afford things, take my friends out to dinner, whatever it was. And then I really got interested in the art world, not just art but the art world, and meeting artists. I started coming to New York, and it was just good for me. It couldn’t have been better.

NA: But could you have started out anywhere else besides LA? It seems like there was a particular energy there.

LG: I suppose New York would have been ground zero for art, but maybe it was better not being in New York. I don’t know. It was good that I was in LA because I think LA is really, after New York, the most important city for art. Maybe not for the business of art — that might be London now, because of all the money in London and the auction houses, so I think in terms of the economics of the art world, I’d say London is the second city. But for the people who make art, for the artists and for young galleries, LA is probably the second most exciting city. Some people say it’s even more interesting than New York, and that’s a conversation. I mean, that’s a conversation, but certainly it rivals New York.

NA: I suppose it feels more like a community, because of the art schools and the fact that a lot of artists teach.

LG: Yeah, there’s a lot of great artists that work in LA, and that’s been a constant since the 1950s.

NA: So what was that world like? Who was in it? People like Chris Burden, Baldessari…?

LG: I’ve never worked with John Baldessari, but I knew him socially, we became friends, but I’ve never dealt with his work. But Chris is an artist I started working with early on, right at the very beginning. And we still work together. Which is nice, you know — it’s nice to have that continuity. I think I first showed Chris in 1977 or ’78, I can’t remember which. One of my very, very first shows of a single artist. We’re really proud of the long association. He’s a great artist.

NA: Were there other people that were pivotal for you at that moment, where you thought, I really want to work with —

LG: You mean artists?

NA: Yeah.

LG: Well, Vija Celmins was a new artist… We showed her prints — one of my first shows was her prints and all of the lithographs that she’d made. I got them together and made a nice exhibition. But yeah, you realize that what’s important is to show the best art you can, and when you’re starting out you don’t have the access, you don’t have the money, and you don’t have the knowledge, even. I mean, I realized early on what would make a gallery interesting would be showing good art. Which is kind of obvious, but… Something that I’ve always paid attention to is to work with the most important artist that I could.

NA: Yeah. But you obviously have an eye.

LG: You have to have an eye if you’re an art dealer.

NA: And I’ve heard from —

LG: Even a bad eye is an eye. [Laughs]

NA: At least it’s distinctive. But I’ve heard from a lot of people who know you that you have a sort of photographic memory, or just a really good ability to —

LG: I don’t have a photographic memory.

NA: No?

LG: I have a select memory.

NA: Or a good visual memory?

LG: Yeah, I have a good visual memory. I’m good with faces, but names — I get in trouble a lot, I can’t seem to remember people. People think I’m rude. As a side comment, you know, I’m not being rude, I just kind of blank out.

NA: Yeah. You have a… persona. Now, do you remember the first piece of work that you bought for yourself? Something you just had to have and live with.

LG: I think one of the first things I bought was a drawing by Vija Celmins that was eleven hundred dollars and I bought it from a collector, a great collector in LA named Barry Lowen, whose collection all went to the Museum of Contemporary Art in LA when he died. He was a young man when he died, he had AIDS, and he was a very good friend of mine. We used to do a lot of business and became really good friends. So the Celmins… I remember it was eleven hundred dollars, and it’s always out on loan, I think it’s at the Pompidou or something, but I’ve kept that drawing since the Seventies. That was one of the first. That was a lot of money for me to spend — eleven hundred dollars for a drawing. I really loved the drawing, and I knew when I bought it that I’d made a good buy, even though it was not cheap and Barry Lowen got the proper price. I knew it would be worth a lot more.

NA: What’s the drawing like?

LG: It’s a pencil drawing of the ocean.

NA: I asked you about Cy Twombly, but are there any other artists that you felt especially close to? I mean that you had either a long relationship with or were intimate with or… I’m sure you’re close to all your artists, but —

LG: Well, Richard Serra is an artist I’ve worked with since 1982, and he’s somebody I’ve had a long relationship with and worked very closely with. It was nice when Cy and Richard were both alive. Richard’s one of the great living artists, and somebody I enjoy working with.

NA: Would you do anything for him? I mean, if he built a sculpture that didn’t fit into your gallery, would you find a way to accommodate it somehow?

LG: We’d probably try. You know, put it outside. [Laughs]

NA: Are there any others?

LG: There are so many artists I enjoy working with. I just mention Richard because I’ve worked with him for thirty years and I mention Chris because I’ve worked with him even longer. I mean I’m not going to say which artists I’m not close to—

NA: Of course.

LG: But I enjoy working with artists. It’s a real challenge and it’s a real responsibility, because you’re responsible for their livelihood, you know? Seriously. And they’re just very interesting people for the most part. They’re usually pretty smart. I just like the whole… the relationship between the gallery and the artist is a very interesting thing, different with every artist. The gallery stays the same, in a way, but the artist’s relationship changes, so it’s one of the things I really enjoy. I like engaging with artists.

NA: If you had to have Thanksgiving with an artist or a collector… I mean, what’s your comfort zone?

LG: I’m comfortable with both. I like being around collectors, you know, because it’s an occupational necessity, but also, I must say — not to flatter any particular collector, but art collectors are usually pretty interesting people. The fact that they’ve chosen to spend money on art… I mean, people who really collect, on an ongoing basis. Not just somebody who’s decorating their house, but somebody who’s really engaged with art and thinks about it, evaluates it, buys it, enjoys it, and talks about it — that’s what I’m talking about. Somebody who’s just, “Alright, I have some stuff on the walls" — those can be good customers, but that’s a different kind of thing. It’s great because as an art dealer you get access to people that are quite fascinating, you could even say important people, that you wouldn’t have access to if you were in some other line of work. You get a window into a world that probably isn’t that easily accessed.

NA: Were there any early collectors that you worked with that were especially on your wavelength? Or with whom you were very involved in the building of their collections?

LG: Yeah, a couple. Probably the three that stick out would be Eli Broad, Si Newhouse, and David Geffen.

NA: I wanted to ask you a bit about —

LG: This is going to go a long time if we’re going to cover ancient history…

NA: [Laughs] No, no, I just want you to be comfortable! Yeah, no, I know, I know —

LG: We’re still back in the Seventies.

NA: Okay, I’ll jump around a little bit.

LG: You better jump around.

NA: I’ll jump around.

LG: We’ll have to move this a little faster.

NA: Alright, alright, alright. But it’s so good —

LG: It might be good but I still have auctions starting this evening.

NA: Sure, of course. Okay. So, your gallery has become global. It’s sort of everywhere, situated in vastly different contexts. Has the art become homogenized, in the sense that you’re selling the same things in Hong Kong that you are in Athens or … wherever?

LG: Do we target certain types of artists for different parts of the world? Not really at all. We basically show the same artists everywhere. The artists we represent, the estates that we represent — we try to make sense of it, and it’s complicated because with this many galleries you have to be very focused on the work. With art — it’s not like it’s a global business like a fashion business, where you can just keep opening stores, just have more production and so on. Artists make work at the pace that they make work and you can’t ask an artist to crank out — I mean, it’d be nice [laughs] — but the reality is, you have to be respectful of that, and it’s tricky. It’s very demanding. But we don’t really say… in Italy, let’s have an artist that Italians would like. The market’s more —

NA: Sophisticated, in a way.

LG: The modern world is much more… contemporary. People look at the same things, you know, whether it’s in Hong Kong or Athens. And so we just work with the artists that we represent, and try to juggle it all.

NA: And about Abu Dhabi — I’ve followed that evolution a bit. And I wondered whether you were aware of what was happening in the Seventies in Iran, with the royal family, collecting—

LG: Now I am. I wasn’t aware at the time, though. I was kind of oblivious to that sort of thing.

NA: I just wonder if you see any corollaries.

LG: Well, yeah. I mean, hopefully, it ends better. But yeah, you have a very wealthy royal family that’s buying art — and I think that’s great, by the way, you know the Shah had a museum and people could go look at the art, it’s —

NA: Still there.

LG: To be honest with you, what’s the difference between that — I don’t want to get into politics, but you know, the Rockefellers bought art and they put it in the Museum of Modern Art and people from all over the world can go look at it. So I think it’s great that you have a royal family in Qatar or in Abu Dhabi—

NA: That has a public —

LG: That has the means and the desire to build a great collection, and then you share it with the world — or certainly, share it first with your country and the people that live in your country. But it’s great. I think if you have the wealth to do that, and assuming that people are being taken care in the other aspects of their lives—

NA: Why not invest in it?

LG: You know, why not? It enriches the country, I think.

NA: You mentioned that in college your world was more wrapped up writing and music. Is that still true? What do you do when you’re not involved in… this? I’ve heard you’re into jazz —

LG: I work a lot. I spend most of my time working.

NA: Do you watch stupid movies?

LG: Do I watch stupid movies?

NA: And also good movies!

LG: Yeah, I like movies. Yeah, I like movies.

NA: Are there any directors that you’re really especially into?

LG: I like Roman Polanski. I like his movies, and… I love Stanley Kubrick. He’s dead, but…

NA: Still great.

LG: Two of my favorite directors.

NA: And music?

LG: Uh… music. I like jazz a lot. I just joined my very first board. I’ve never been on a board, but I just went on the board for Jazz at Lincoln Center. I’m very happy about that. Good jazz has been a big part of my life, as far as my interest in music, and… . It’s kind of weird now with music, the way technology is, with downloading and iPods and electronic distribution and it’s kind of — you miss something, I think.

NA: Like the texture of vinyl, and…

LG: Yeah, but not just the vinyl, I’m not a vinyl junkie. It’s more that… music has become so seamlessly distributed that it loses some of its connection with people. I don’t have any nostalgia for vinyl, but it is nice when you really like to put on something and listen to it, particularly with people that like to listen to it. Now you come to my house, it’s like, stick the iPod in and turn it on. It’s very convenient, but it also… slightly numbs the experience, I think. I used to have a store in my neighborhood in East Hampton where I used to love to go on a Saturday and buy CDs and come back and listen to them. That’s not that long ago. The good side is, everything is more accessible and maybe cheaper. But the personal connection between the audience and the music in some ways is lost.

NA: Yeah, you said seamless, I think it’s like an —

LG: Do you agree with me?

NA: Yeah, it’s like an elevator, I mean how music is everywhere, in the atmosphere —

LG: Yeah, there’s no background.

NA: Just a couple more questions. I know that you invest a lot in good catalogs. I mean, it seems like you really care about print culture, and I just wonder if you have any favorite books? Do you read art magazines at all?

LG: Very little.

NA: Yeah, they’re pretty wordy right?

LG: I honestly have to confess I don’t read art magazines.

NA: Yeah, they’re terrible [laughs], I mean they’re —

LG: I don’t think they’re terrible, I just don’t read them. I read other kinds of magazines.

NA: Like what?

LG: I like magazines. Well, now I’m reading a lot of design magazines because I’m building a house. I’m building a new house here in the city, so I’m reading a lot of design magazines trying to get ideas and things to feed to my architect. So that sort of thing. And then I love cars — I’m a car junkie, not a big car collector but I love cars, so I read car magazines. I read news magazines, occasionally. And I read books a lot. I’m more of a book reader.

NA: What are you reading now?

LG: I’m reading a book called Sutton.

NA: What’s that about?

LG: It’s about a bank robber named Willie Sutton who was almost a folk hero. He never shot anybody, never used a gun. I wouldn’t have read it because I’m not particularly interested in bank robbers but the writer is a really, really good writer and it’s a very sensitive, well-written book. I recommend it. So it’s not like I’m particularly interested in the topic but it’s like a character from our past that somehow relates to the present.

NA: Okay, I was going to —

LG: Okay? Thanks.

NA: Oh, do you want to? Really?

LG: Yeah, let’s stop.

.