Throughout the latter half of the 1940s, the reigning champion of squash was a dapper Egyptian by the name of Mahmoud El Karim. Tall, elegant, and handsome, Karim embodied all the attributes of the consummate sportsman. Ever cool, his style was well admired both on and off the court. He donned smart white flannel trousers, paired with delicate cashmere sweaters. It is said that his movements were so graceful, no one ever heard his feet touch the ground.

By 1950, Karim was the top professional at the prestigious Gezira Sporting Club in Cairo, with four British Open titles under his belt. (At that time, the British Open was the equivalent of a world championship.) In other words, things were looking good.

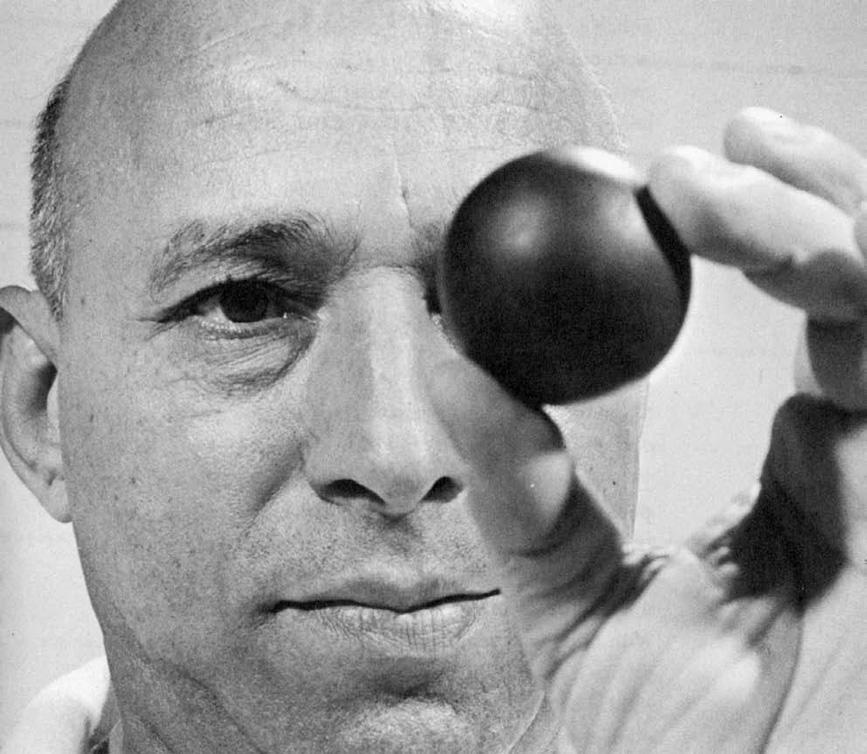

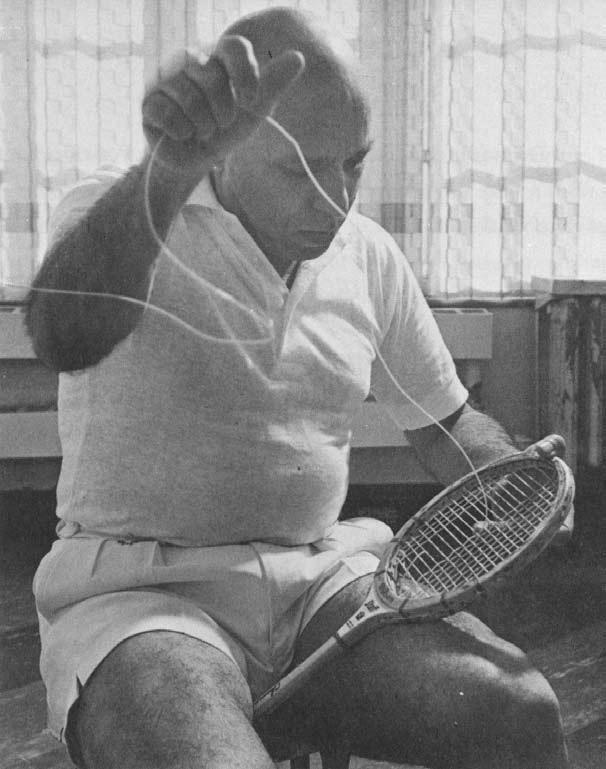

But the dapper Egyptian’s luck would take a turn for the worse in 1951, as an unknown man by the name of Hashim Khan would make his debut in the prestigious world of international squash. Sent by the newly born nation of Pakistan to compete in the British Open, Khan hailed from a small Pashtun town outside of Peshawar, where his father was once chief steward of the colonial officers’ club. Age thirty-seven at the time, he was 5’4” and balding, carried with him a Buddha-like potbelly, and, appallingly, wore short shorts in clubs where starched pants were common decorum. Khan was literally self-taught; he had mastered the game through endless matches of what he referred to as “Hashim vs. Hashim.” In other words, this smalltown Khan embodied none of the attributes typical of his fellow sportsmen. The matches he played in Britain were the first for which he had ever worn shoes.

But the story of Hashim Khan is the story of the victorious underdog — he’s the true-life version of Daniel LaRusso, Happy Gilmore, and the Jamaican bobsled team rolled into one. To the disbelief and chagrin of squash aficionados everywhere, Hashim Khan beat Mahmoud el Karim three sets to none that year — and again the next. By 1958, at the incredible age of forty-five, Hashim had accumulated a record seven British Open titles from various opponents, including his younger brother Azam Khan and cousin Roshan Khan (Hashim was the first in an extraordinary dynasty of Khan squash players who would dominate the game for the next fifty years).

Although Khan’s early playing style was simple and inelegant, his speed, fitness, and understanding of the game were wholly unrivaled. Many consider Khan, a true flower, to be the first squash icon. His fateful timing would also make him Pakistan’s first national hero, winning his inaugural British Open just four short years after partition from India and inextricably linking him to the establishment of his young country.

But Khan is a humble man and steers clear of heavy praise. His public voice is limited to a neverending stream of charming and often comedic truisms (“Watch ball, walls don’t move”) delivered in his signature laconic English, a style that could best be described as a cross between Mr. Miyagi, Yoda, and a fortune cookie. The resulting persona is almost too perfect, too caricatured, too sweet. One is left wondering if Khan is not playing life with the same keen cunning with which he played his sport; if his overly amiable and perhaps faux-naïf character is in large part what made his acceptance into squash culture so seamless. But just as we will never know if Azam Khan deliberately lost those three British Open finals out of respect for his older brother, we will likewise never know what was going through Hashim Khan’s mind as he single-handedly executed his glorious athletic coup d’état.

We can all, however, stand to learn something from the squash champion’s 1967 quasiautobiographical Squash Racquets: The Khan Game:

Keep eye on ball.

Move quick to “T.”

Stay in crouch.

Take big step.

Keep ball far away from opponent.

Have many different shots ready so opponent does not know what you do next.

Do not relax because you play good shot; maybe opponent retrieves that ball; better you get ready for next stroke.

Soon as can, find out where opponent has idea to send ball, then quick take position for your return shot.

Have reason for every stroke you make.

After passing the British Open torch to his brother Azam, Hashim accepted a lucrative professional post at the Uptown Athletic Club in Detroit in order to support his (impressive) family of twelve children — five of whom would become squash professionals themselves. Today, a hobbling ninety-four-year-old Khan, now even more diminutive, resides in the quiet, middle-class Denver suburb of Aurora, Colorado. There he’s a revered fixture at the local athletic club, where if you can’t find him playing a geriatric (read, stationary) version of his favorite game on the Hashim Khan Court, you can probably find him loafing about the Hashim Khan Trophy Room, dispensing Hashim Khan wisdom to his myriad fans. “I do not want to talk like I am proud man. I tell you such things about me so you can understand why I win matches. Maybe they help your game!”