Javad Yasari is Iran’s Willie Nelson, and like the country legend, he is the voice of the road. The rhythms of Javad’s music have kept truckers awake across Iran’s deserts for thirty years. Groups of young men in alleyways, fueled by a bottle of homemade vodka and cheap cigarettes, still serenade the night with his songs.

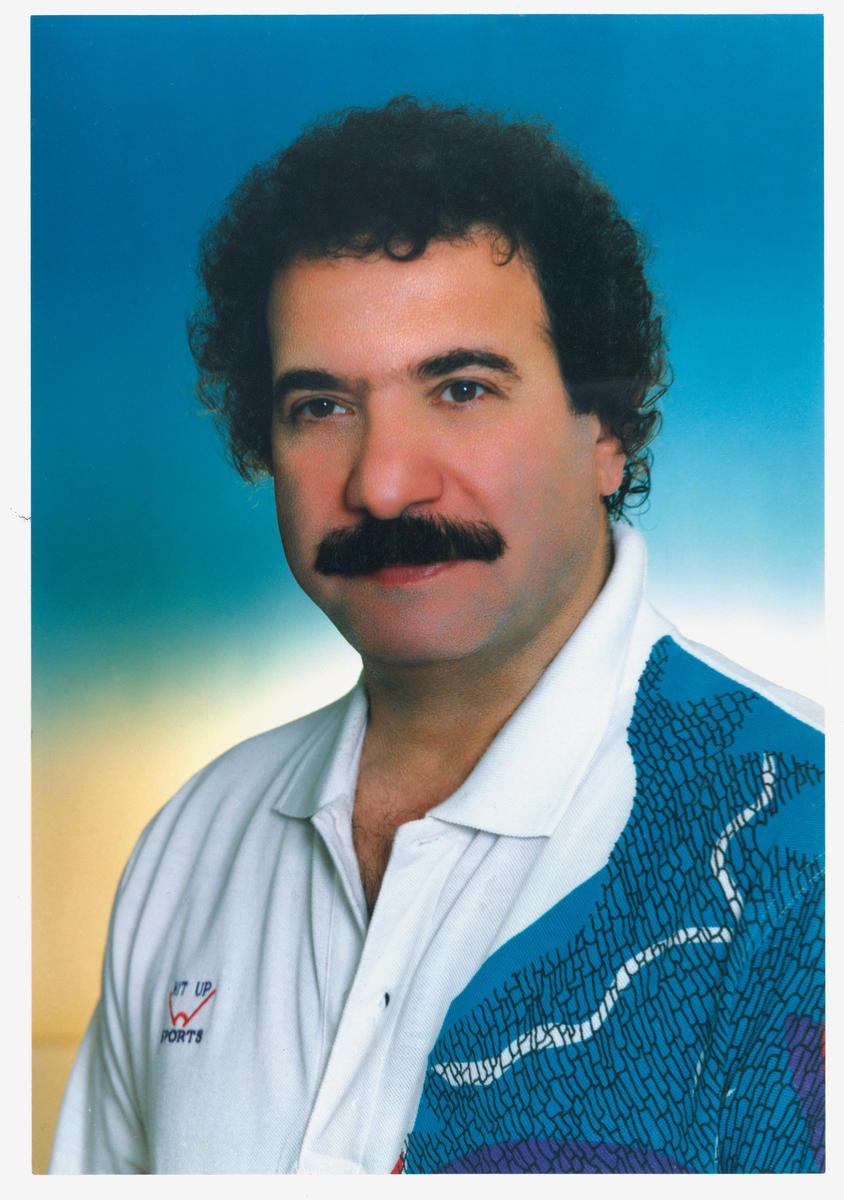

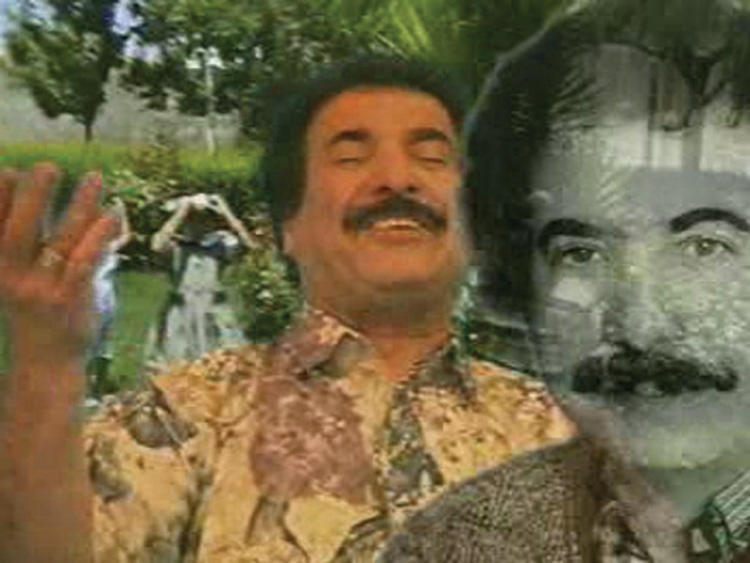

An ex-National Team wrestler, Javad is a superstar in his own eyes and the eyes of Tehran’s bazaar. But nobody knows what he looks like. At sixty-one, he’s keen to point out which wrinkles he wants a photographer to Photoshop, but apart from the odd newspaper article, his face has had minimal airtime. His star rose in the late 70s at Lalezar, the downtown club strip where Googoosh thrilled a champagne-sipping clientele, while the storm of revolution was gathering. 1979 turned the lights out on Lalezar and the cabarets of south Tehran, and Javad’s music went under the counter.

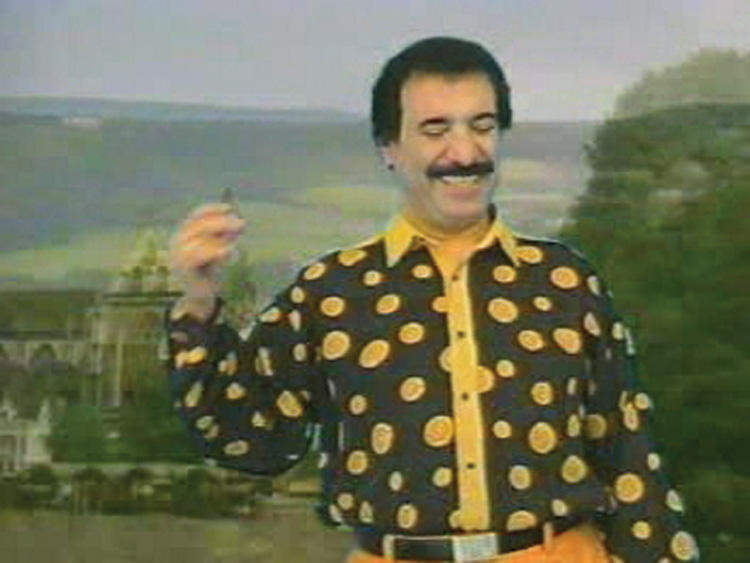

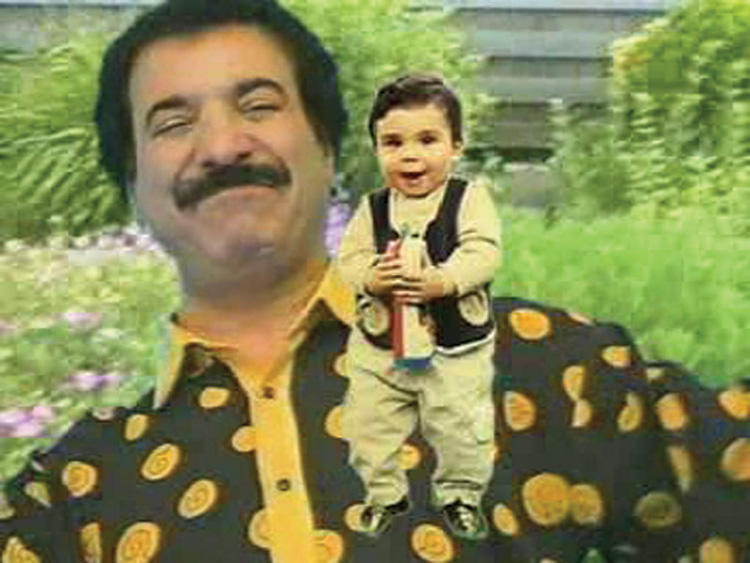

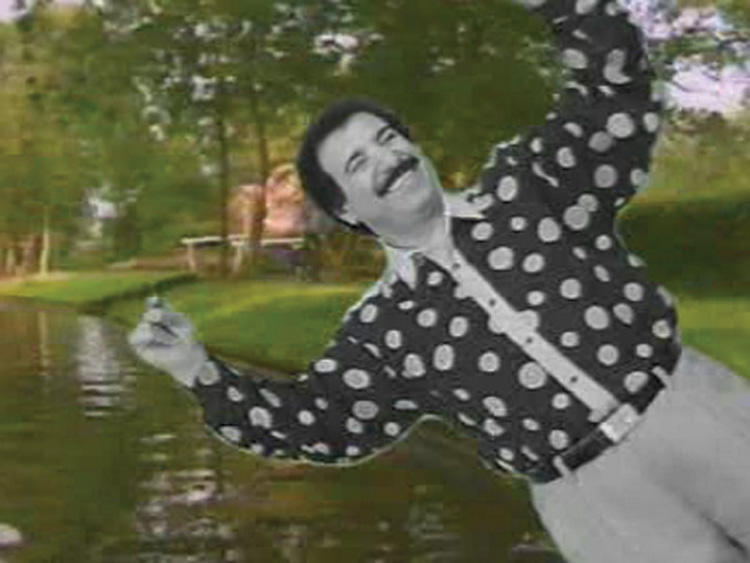

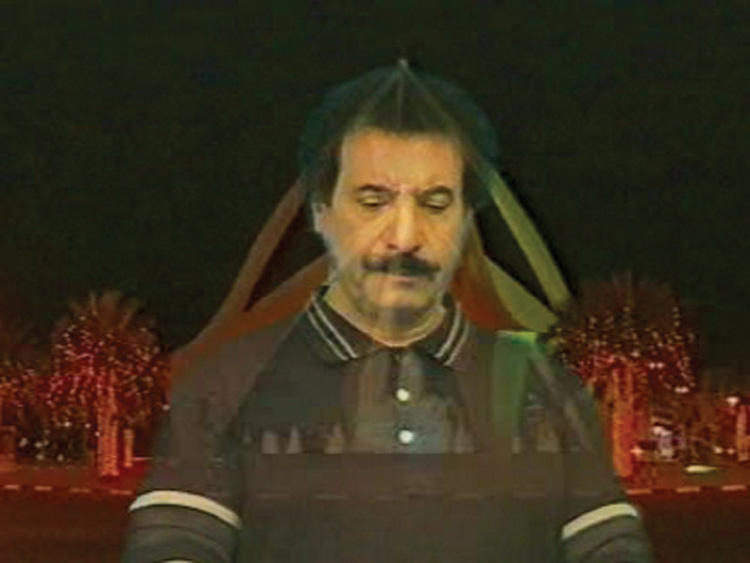

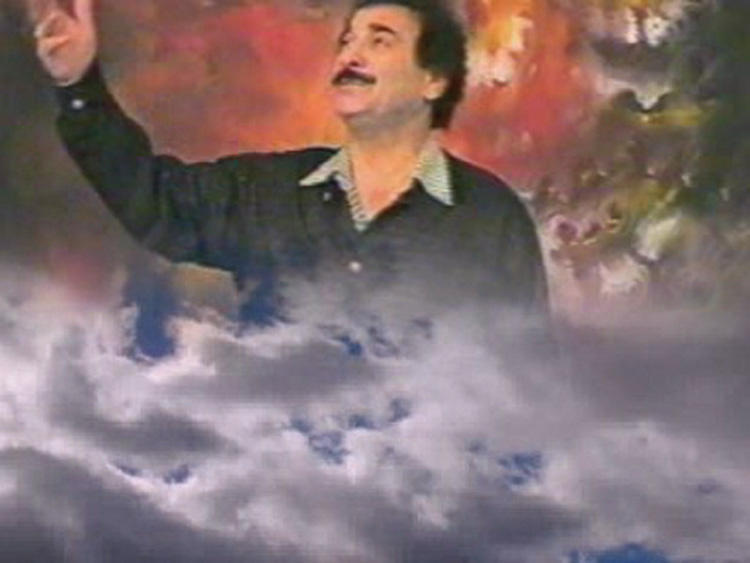

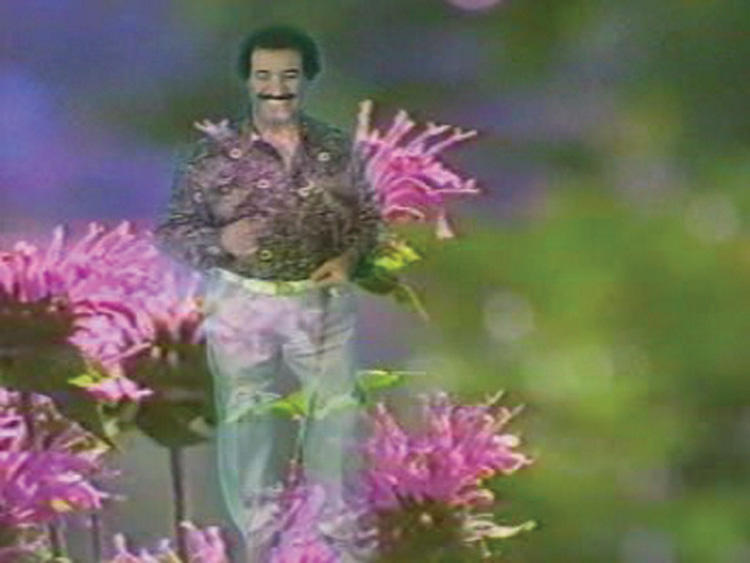

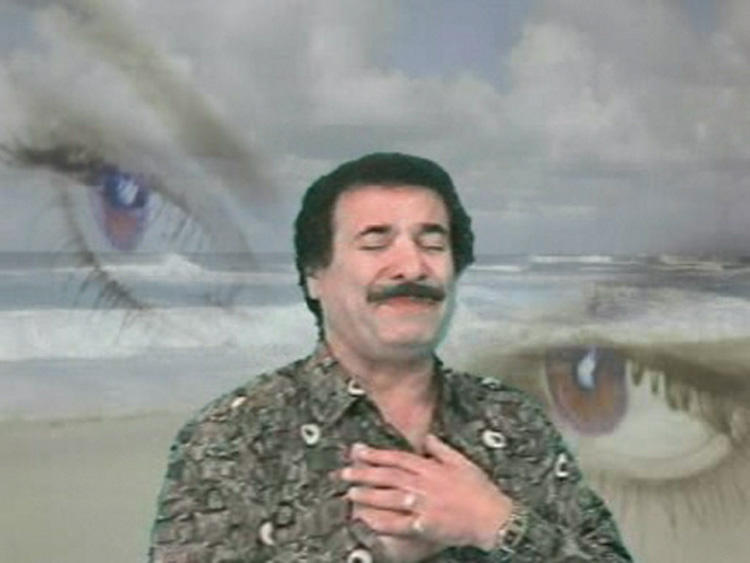

Iranian melodies layered over Arabic rhythms, his songs are emotional rollercoasters of love and loss, loneliness, and the grace of Imam Ali. His one and only VCD of music videos, produced illegally, is a fruit salad concoction of his family snaps, psychedelic fade-ins, and hip-swinging, finger-clicking Javad clad in polyester. All of the clips feature images of him singing superimposed over a range of background footage, from images of Tehran to eager dolphins behind the glass of an aquarium. In one, he swims in and out of focus against images of Belgium, the home of his oldest son, who made the eccentric suggestion that Javad slap himself over shots of a local church. Bought from a street seller, it quickly became our late night party anthem. Even as I describe the scene to him, he’s having trouble visualizing it: a bunch of drunken kids in north Tehran, jumping on expensive sofas to his music.

His surprise is understandable. Javad’s songs are downtown anthems. His tales of family, folks back home, Mama and the love of the Shia Imams are sung in the same accent as boasts about knife fights in tea houses all over Iran. There’s a class divide between those who glow with fondness at his name and those who look at you sidelong when you mention it.

Although his music is beloved by the traveling man, Javad himself hasn’t moved very far. He owns a secondhand fridge and television shop in Shahpour, where he was born. Tehran is a two-tiered monster of north and south that has exploded from three million people in 1979 to about sixteen million today. Much of what is now highway and high-rise was fields and orchards two decades ago, but Shahpour was always at the city’s downtown heart, just south of the bazaar. In the mornings, Javad sits outside his shop in a dark silk shirt, a stone’s throw from the house where his widowed mother single-handedly brought up a large family. Javad is the youngest child of seven and beams when I tell him seven is a fairy tale number. His life has been marked more by frustration than luck, but he recounts it with the panache of an old-school storyteller.

Thursdays evenings in his youth, singers like Hassan Shahrestani (oddly nicknamed “Hassan the Crotch”) and Seyed Karim, a joke teller who is now getting laughs in LA, would gather in coffee houses to smoke and sing. One evening, during his days as a professional wrestler, Javad went to a coffee house with his teammates. They had been listening to him in the showers for years and egged him on to perform. “That was how it began—the next week everyone turned up with tape recorders.” From there it was a short walk to Lalezar and the Zangouleh recording studio run by two famous cabaret dancers, Afat and Mahvash. “Afat cried when she heard my voice. She told me I had something really special,” he recalls. At Zangouleh he recorded the first of his five cassettes with Hassan Shahrestani, tunes laid over backing music of nightingales and birdsong.

Javad was in heaven, but his family was less than supportive. “At home, singing was haram. My brothers sang at the heyat (religious halls built in honor of Imams) but they thought singing was the work of the devil, and one by one they abandoned me.” It’s therefore ironic that the love of God features in nearly every one of his songs. These influences stayed with him, and after his first cassette caught on in the bazaar like wildfire—“not a tape was left on the shelf; workshops were lining up to copy it”—he got his first gig in Lalezar’s Theatre Dehghan. He remembers bending down to kiss the boards before he walked on stage. “It’s what I’d always done when I wrestled. The stage was sacred.”

Javad soon moved to the larger Theatre Pars, the haunt of singers such as Nematollah Aghasi, Ali Nazeri and Majid Farhang. His first night there, he sat down on the stage to sing, like traditional folk singers. “I started a fashion wave. After that, all the singers sat down on stage, and the audience went wild.” Javad is devoted to his audience, who he calls “his people.” “That was the secret of my success,” he explains. Javad and other kuche bazaari (streets of the bazaar) singers were the first group to sing in the language of the street. His songs resonated, and old women still track him down to thank him for a son saved from opium addiction by his song “Mother,” or a strong child conceived to the strains of “Yasari’s stories.”

“I’ve seen lines from my songs written on people’s graves,” he beams with pride. “I have always had a message for people. I want to guide people with my songs,” he says. “I could show you more than a hundred families that have stayed together because of my song ‘Child.’” His music certainly brought his family back together. “When I became famous, one by one my family all came knocking, asking to make up and wondering how much I was earning.”

Javad doesn’t feel modern pop is up to much, though he’s happy to take what he likes from it. “I sing with love, I love my work. Now people just make music for dancing, for pleasure, not for true emotion. Great music should be like a pair of black shoes. Good for a wedding or a funeral.”

Javad’s big hit before the Islamic Republic killed the party of Lalezar and the kuche bazaari singers was “Sepideh Dam” (Sunrise). “It caught on down here, and up there,” he says. Its story is pure romance. A man kills for love and is sentenced to death. In prison, he learns that his beloved has betrayed him for another man. As a last request, he asks that she be brought to the execution. He spends his last night writing a wistful love poem, and at the final moment stands before her without bitterness and sings: “You threw our life to the winds…”

“Men and women about to divorce would get back together,” he says. “It was a song for mothers, lovers, anyone who’s lived.” Like the song’s hero, Javad isn’t bitter about life’s ups and downs— not about his career cut short on the cusp of success, nor about his second son who died young in a gas accident, nor about the fact that he can’t read or write (“I went out to work as a child. There was no time for school”). There is only the slightest hint of bitterness when he explains how the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, which has never allowed him to record in Iran, recently gave permission for another younger singer to record and perform “Sepideh Dam” live.

Javad comes from a group of artists who got lost between two extremes: The Pahlavi regime was more interested in progressive French jazz than kuche bazaari music, and they were kept out of the mainstream media under the Shah. And in 1979, although the kuche bazaari singers came from the hotbeds of the revolution, their concerts and recording went out the window along with Googoosh and American rock.

After the revolution, Javad’s cassettes were sold illegally and his music lived on as part of a culture that perhaps changed least with the events of ’79 but has never really had its time—the hard working van-driving family man who loves Imam Ali like a father, but who also loves music, tall stories, and the camaraderie of arak sessions. Who spins yarns of nights in Cafe Sousan and Cafe Moulin Rouge and who has never brought his wife to a concert.

Javad skips lightly over the intervening twenty-six years spent singing in nightclubs and halls from Dubai to Australia. For a singer so in love with “his people,” the gigs were little more than stopgaps. He’s back in Tehran indefinitely. “I have no bookings for the moment.” And he’s planning a new video. “I never give up hope,” he says. “There could be one day left till the end of the world, and I would still hope.” He smiles and raises another glass of arak, and we tip back the shots with a toast. A couple of shots later and we’ve all signed up for bit parts in a video that we promise will take him to the stars. He’s excited by the prospect, though international stardom has never been a priority. The singing legend who has no face recognition and no producer, and who still isn’t allowed to give concerts here, won’t give up on Iran. “You have to find success at home, if it’s to be real. I sing for my people. Nothing else matters.”