THE MILLIONAIRE

Gemeiz is a poor showman who works in a nightclub. One day millionaire Assem El Isterliny visits the nightclub, visibly shaken after shooting a young man he caught with his wife. Following his servant’s advice to hide for a few days till things cool down, he decides to employ Gemeiz, a dead ringer for Assem, to take his place as his double. Gemeiz goes to the millionaire’s palace, where Assem’s beautiful wife Camillia and his hysterical sister live. He soon finds out that the young man wasn’t killed (the servants had exchanged the gun’s live ammunition with blanks) and is actually Camillia’s poor brother. After several scenes in which Gemeiz’s tomfoolery proves much more effective than Assem’s rationality in solving the problems of Assem’s life, Gemeiz becomes profoundly bored with living in the palace and attempts to leave. Of course no one believes that he’s not Assem, and the family calls a psychiatrist who decides to lock him up in the “ward of the sane.”

SHADES OF MADNESS

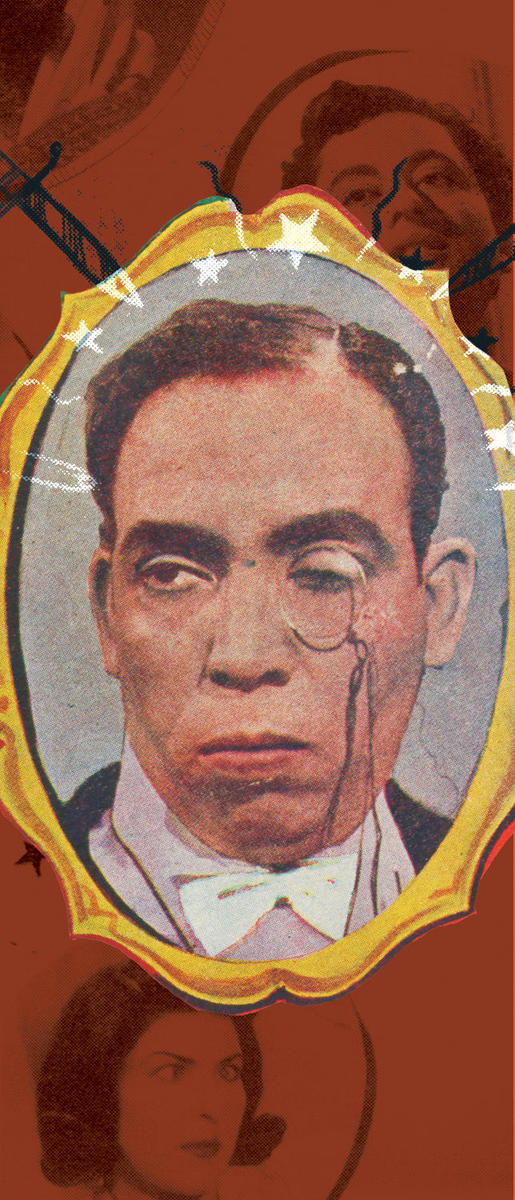

Ismail Yasin, arguably Egyptian cinema’s most famous comedian, had his first leading role in The Millionaire, directed by Helmy Rafla, an industry stalwart with many a comedy under his belt. This was the first in a long series of films throughout the 1950s, in which Yasin assumed what became his trademark persona of the fool who embarks on quixotic adventures, narrowly and miraculously escaping various dangers. Yasin’s ability to contort his face in one million different funny ways, combined with his general appearance — short and bald with a prominent mouth — helped make him an ideal vehicle for a particular type of comedy, one based on exaggerated physicality. In these comedies Yasin’s deviant logic both makes us laugh and allows us to see the world around us through different eyes.

Central to The Millionaire is an extended song and dance spectacle that takes place in the madhouse. It’s a scene that has had a huge impact on popular culture, in part because it references an archetype while producing something completely new. The madhouse is where fools converge and indulge in all sorts of language games. They sing subversive songs, gesticulate wildly, laugh insanely, and break taboos casually; all is acceptable under the umbrella of insanity. The way madness and entertainment meet in such spectacle has proven highly successful with audiences and remains a staple of Egyptian cinema to this day. There are critics who attack popular comedies for their supposed lack of a narrative structure. But they’re missing the point. These comedies are meant to be episodic, situational, and physical. In them the figure of the comedian focuses on all that is irrational, fragmented, and broken. The comedies become the inheritors of an Arab heritage in which the stories of madmen are often latently critical of power and authority (stories attacking with sarcasm tyrants and their casual abuse of the people abound). Yasin’s is therefore the natural evolution of the archetypal comedic character in both classical and popular Arab culture.

STEPS TOWARD PARADISE

Step 1. Exorcism

Gemeiz is our guide to the alternate universe of the madhouse. To enter, it’s necessary to pass through a series of tests. A doctor first asks Gemeiz a couple of simple questions. “What powers the tram?” Gemeiz replies, “The conductor’s whistle.” When asked how many days of the week there are, his response is six, because Friday is a day off. These answers make the doctor question Gemeiz’s sanity.

The doctor then calls a male nurse to administer a “treatment through music” — what he describes as a highly modern practice. We soon discover that the practice isn’t modern in the least, but rather, an entirely medieval affair. Gemeiz is showered with cold water for two hours. The male nurse (played by Riad El Qasabgy, Yasin’s archnemesis in countless films, the Tom to his Jerry) then puts on an Oriental dance tune, forcing Gemeiz to dance as he is interrogated. “Are you a man or a woman?” Gemeiz’s inconclusive answer is, “All that remains is for you to ask whether I am pregnant”; the nurse repeats his question, at which point the answer becomes, “Well, now I am a woman.” The situation is reminiscent of exorcism rituals, in which the exorcist asks the patient questions that allow his other “repressed” persona to appear. As it happens, the woman who appears out of a man became the subject of another Ismail Yasin vehicle, Fateen Abdel Wahab’s 1954 Miss Hanafy.

The doctor, now absolutely convinced of Gemeiz’s insanity, asks the nurse to take him to the ward of the sane. The name, highly ironic, helps highlight a series of oppositions and paradoxes that mark the film. The contrast between poverty and wealth, a common enough dichotomy in the melodramas of the period, looms large. (The binary opposition between Assem El Isterliny and Gemeiz is also clear; Assem is highly rational and jealous, an aristocrat of Turkish origins, while Gemeiz is humorous and foolish, a man of the people who by film’s end will marry a servant.)

Eventually, Gemeiz is literally pushed into the ward. As he hesitantly descends the stairs, we’re reminded of myriad figures who’ve descended into the nether-world in myths. This alternative world is where our anti-hero takes active steps toward rediscovering himself, letting unconscious drives free; his road to knowledge passes through folly.

Step 2. Redemption

Grand in scale and flanked by palatial columns, the ward is a fantastical place. The musical background, a drone-like hum (probably a recording of musicians warming up – an unlikely, almost avant-garde choice, for a commercial film in the 50s) induces a state of calm, expectation, mysteriousness, and fear that both reflect Gemeiz’s inner state and provide the overture to the music of the coming spectacle. The line between real and unreal, the visible and invisible, is subtly indicated. Gemeiz plays an invisible qanoun toward the end of the scene, and we magically hear the tinkling notes of a virtuoso instrumentalist. When one of the inmates shouts that he is a train and starts to imitate one, we hear the sound of a full-on locomotive, and when another inmate warns him against falling into the water, we again hear the rustle of water.

Suddenly one of the madmen, as if he were announcing royalty, declares the arrival of “the sane ones” by blowing a horn, and the show, finally, begins. The ward, just a moment ago a ship of fools, is suddenly transformed into a Shaabi carnival, as the entire chamber breaks into song and dance.

Truly remarkable is the number of celebrities among the extras (fifty, at a minimum) in these scenes, including famous singers and musicians who utter only one or two lines. Serag Munir, whose name appears on the credits equal in size to the main actors, appears for roughly two minutes as the character of the Bedouin hero Antar, the same role he played in Salah Abu Seif’s epic film two years earlier. A series of sketches in which each madman assumes a different historical character follows. The choice of characters is inevitably loaded. Napoleon saunters down the stairs, declaring that he holds a mighty secret, only to start muttering banal inanities. Nero is next (“I will light up Rome with a match”), announcing a glorious speech before breaking into a nursery rhyme.

Antar, the Bedouin Arab hero of legendary strength, also appears. However, when he begins speaking (after a musical introduction that includes bagpipes) we discover that his voice has been perfectly dubbed over by the feminine voice of a young woman. When Gemeiz asks him what happened to his voice, Antar replies that it changed after his last thrashing. Next, an old wizened man appears from under his traditional robes and announces himself as Antar’s lover Abla (traditionally a paragon of beauty and symbol of pure love). The themes of transvestitism and travesty are central to the spectacle and are further emphasized in such details as a cutaway shot of three men clapping in the background; the central figure’s long hair is tied back into two ponytails decorated with flowers in an obvious feminine twist.

Each time a new historical character is introduced, pompous, almost militarystyle music — a complete orchestral brass section — is played. This music, however, soon f lips into the light folk-inf lected baladi music of the time. Whenever one of the madmen starts to speak seriously, the music reverts to Western (Napoleon, Nero) or Bedouin (Antar) motifs. And again they revert to a popular mode when the madness of what they say is revealed. This opposition between Western music and Oriental popular music comes with a series of associations. Orchestral European music here implies rationality, seriousness, authoritarianism, and patriarchal power, while the music of the people carries associations of madness, sarcasm, and breaking the barriers of class and gender.

MADMEN IN PARADISE

At the end of the spectacle, Gemeiz enters a dialogue with a bookish inmate carrying a large pile of texts; he looks like a philosopher. The inmate explains to Gemeiz that the real madmen are actually outside, in the world, and if Gemeiz seeks to leave this “paradise,” to appear sane in the eyes of the world he will have to lie, indulge in hypocrisy, and commit immoral acts. Indeed, the lesson, if one is to glean one, is that history’s leaders and notables are “sane” but miserable; only through insanity can one find wisdom, contentment, and freedom.

The male nurse then reappears to take Gemeiz to see his wife and sister. He proceeds to lie and assumes the persona of the millionaire once again. In this way, he is let free. His final parting words to his fellow inmates: “Farewell to you, happiest and sanest of all people.”