Before there was an Iranian New Wave, there was Kanoon. Founded in 1965 with the blessing of then-queen Farah Diba, the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults — mostly referred to as Kanoon, an abbreviation of the Farsi name — produced books, audiotapes, and films, both animated and live action, for Iranian children from Tehran to Bushehr, Sistan, and Baluchistan. Stories such as Baba Barfi (Father Snow), Amoo Norooz (Uncle New Year), The Journey of Sinbad, or Khorshid Khanoom Aftab Kan (Shine on, Lady Sun) were tales that all Iranian children would come to know and cherish. Prior to Kanoon’s founding, most children’s books in the country were translations of Western classics. There was Pinocchio, The Little Prince, and Tin Tin — all in slightly clumsy Farsi.

The history of Kanoon is equally entwined with many of Iran’s most epic late twentieth-century stories, from Empress Farah’s cultural initiatives to the heyday of the Iranian left to the revolution. Kanoon would become a sort of incubator for some of the country’s most celebrated artists — including Ebrahim Forouzesh, Noureddin Zarrinkelk, and many of the protagonists of Iranian cinema, Sohrab Shahid-Sales, Abbas Kiarostami, and Amir Naderi among them.

The following is the first in a series of conversations in Bidoun about Kanoon. Here, Arash Sadeghi engages his father, the painter Ali Akbar Sadeghi, who is best known for pioneering a style that mixed traditional Persian coffeehouse painting and the surreal, and Farshid Mesghali, one of Kanoon’s most important graphic designers and animators. Among the elder Sadeghi’s most iconic projects during his time at Kanoon was Malek ol-Khorshid (King of the Sun, 1975), a magical animation inspired by the tenth-century Persian epic The Shahnameh (The Book of Kings). Mesghali is probably most beloved for his illustration work on the book Mahee Siya Koochooloo (The Little Black Fish, 1968). Here, the three discuss the founding of Kanoon and its activities up until the time of the revolution of 1979. One way to gauge a nation’s history, after all, is to look at what its children have been reading.

Arash Sadeghi: Can you tell me a little about how you entered Kanoon?

Ali Akbar Sadeghi: After all these years and at this old age, I can’t remember too many details. But I can say that two great people, Lili Amir-Arjomand and Firooz Shirvanloo, created a factory called Kanoon whose goal was to support creativity among the next generation of Iranians.

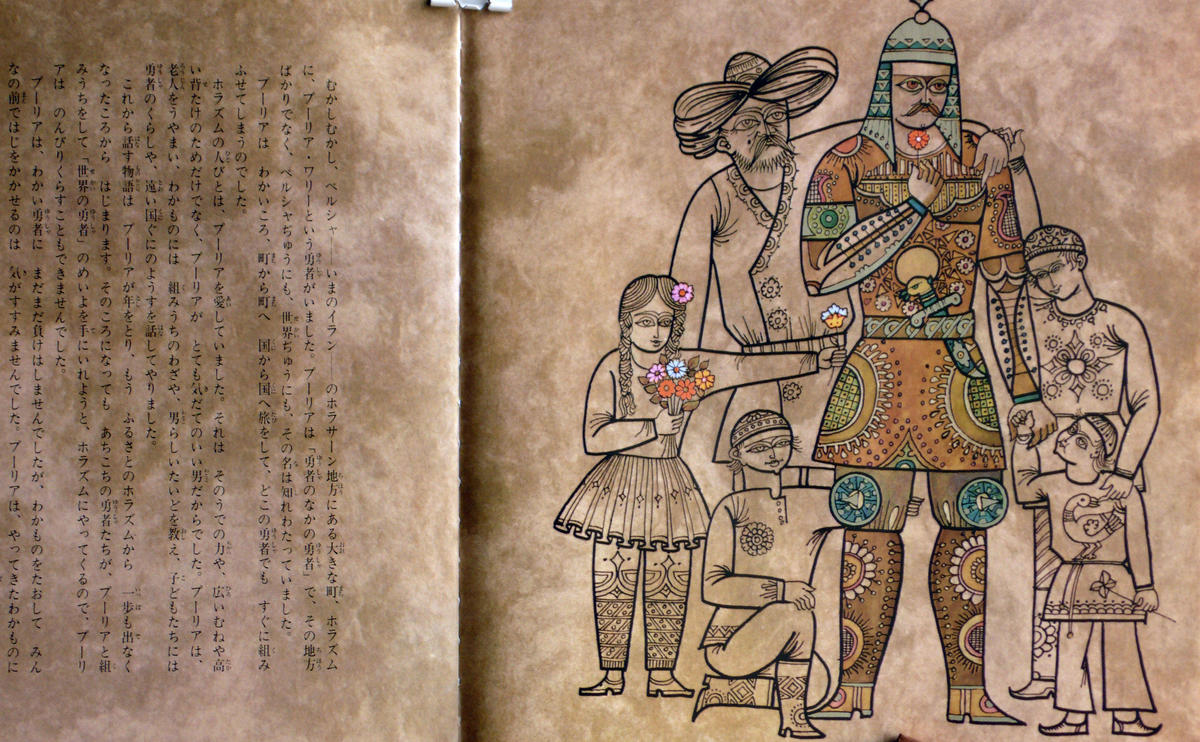

Now, how did I become a Kanooni? One day, Abbas [Kiarostami] told me that Kanoon was to publish a book and needed someone who could illustrate the text in classical Persian style. He asked me to come to their offices and, like that, with the book Pahlavan-e Pahlavanan (The Champion of Champions), my relationship with the institute began. I have the best memories of my life from my time there.

AS: Mr Mesghali, can you tell me about the birth of Kanoon?

Farshid Mesghali: I’m really excited. After all these years, someone is asking me to recount the story of the birth of a revolution. Let’s start.

Farah Diba, the last Iranian queen, had a close friend named Lili Amir-Arjomand. They had been roommates while they were students in France. When Farah became the queen, Lili, who had studied to be a librarian, was appointed head of the national oil company library.

After a short while, in 1965, Lili, with Farah’s support, proposed that a library be built in Laleh Park — it was called Farah Park back then — for children and young adults. This was to be the first specialized library for children in Iran, and they also planned to publish children’s books.

Their first book was The Little Mermaid, complete with Farah’s own illustrations. Many people do not know this and this first book and the establishment of the library were the starting points of Kanoon. In fact, in the beginning, Kanoon’s activities were limited to translating and importing books from abroad.

In 1965, Lili officially launched Kanoon with Farah’s support. She would be the first director, along with a man named Firooz Shirvanloo.

I knew Firooz from many years ago, when I was working at Franklin Publications with Arapik Baghdasarian. Firooz is the most important person in the history of Kanoon, in part because of his political background. Firooz had studied philosophy in England and had come back with leftist tendencies. He was also a member of the Iran-Britain Student Confederation. They were known for their extreme revolutionary ideas.

After returning to Iran from Britain, he was the art director of Payk magazine for young adults, which was published by Franklin Publications. These days you can find the magazine in news kiosks under the name Roshd.

After the confederation became embroiled in a failed attempt to kill the Shah in 1965, Firooz was arrested by one of the Shah’s insiders in the Iran-Britain Student Confederation and sentenced to death. After his arrest, they feared me, too, and I was fired.

Europeans objected to the court sentence, and eventually the Shah forgave them, and the death penalty was reduced to a few years in prison. After winning their freedom, some of them were offered important positions so that they might “rethink” their leftist ideas.

Because of his experience in publishing magazines for children, the palace offered Firooz a position in the newly formed Kanoon. At the same time, Firooz had just founded an advertisement group called Negareh and hired a group of arts and literature students from Tehran University to work with him, including Abbas Kiarostami, Ahmadreza Ahmadi, Nikzad Nojoumi, Farideh Farjam, Arapik Baghdasarian, and myself. Eventually they would all migrate to Kanoon itself. But even after prison, Firooz held on to his leftist ideas, and many of the people he brought into Kanoon with him were leftist writers and researchers.

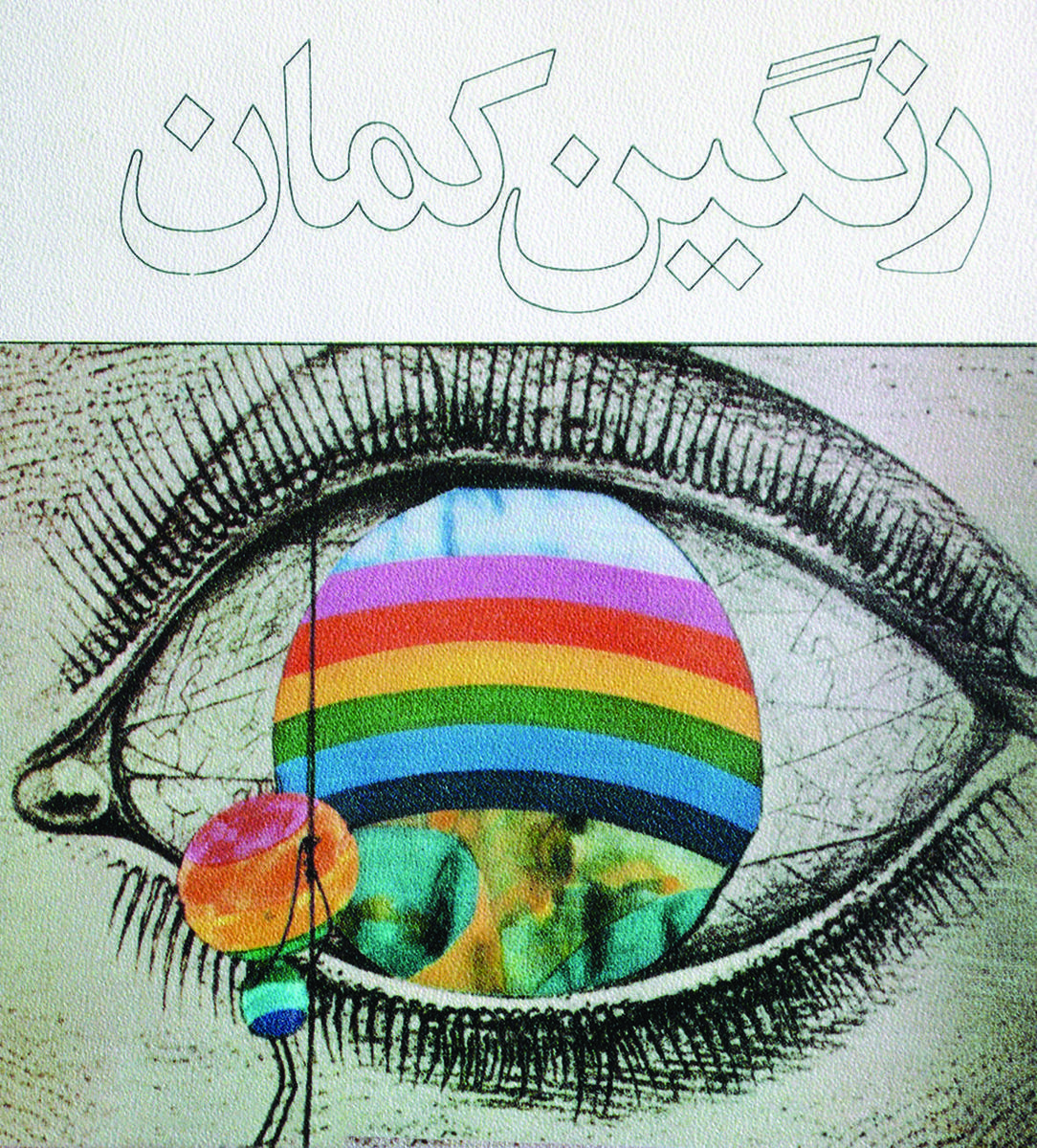

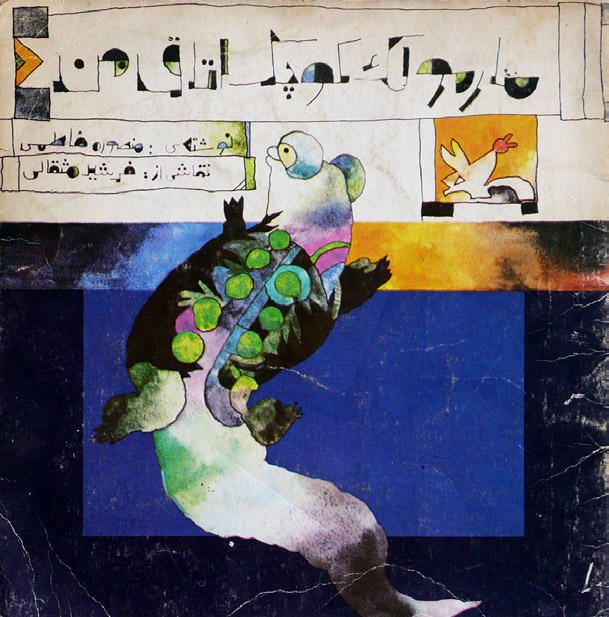

In 1968, Firooz commissioned me to work on one of Kanoon’s first independent books. With the publication of The Little Black Fish written by Samad Behrangi, we gained a lot of attention. I drew the illustrations for that book, and we won the top award at the Bratislava Children’s Book Fair because of it.

[The Little Black Fish is the story of a black fish who dreams of seeing the big blue sea. He faces many dangers, including a heron, which he kills with a dagger. The narrator of the story, a grandmother to many little fish, explains that the little black fish has disappeared by the end — a little like the martyrs who have died trying to find a better world. It was hard not to find political symbolism in this, along with other stories. Incidentally, its author, Samad Behrangi was an active socialist agitator who translated some of Iran’s most avant-garde poets, like Ahmad Shamlou, Forough Farrokhzad, and Mehdi Akhavan-Sales, into his native Azeri language. He drowned in the Aras River in 1967, and his death is generally blamed on the Pahlavi regime.

Also published around that time was Gol-e Boloo Va Khorshid (The Crystal Flower and the Sun, 1967), by Farideh Farjam, illustrated by Nikzad Nodjoumi. This is the story of a flower that miraculously shoots up amid the ice of the North Pole. For a period of six months, the little flower develops a close relationship to the sun. The sun tells the flower about the world and its people. At the end of six months, when the sun has to migrate, the flower asks to move with him. He gets so close to him that the flower wilts and joins the sun forever. Along with The Little Black Fish, The Crystal Flower was honored at the Bologna Children’s Book Fair.]

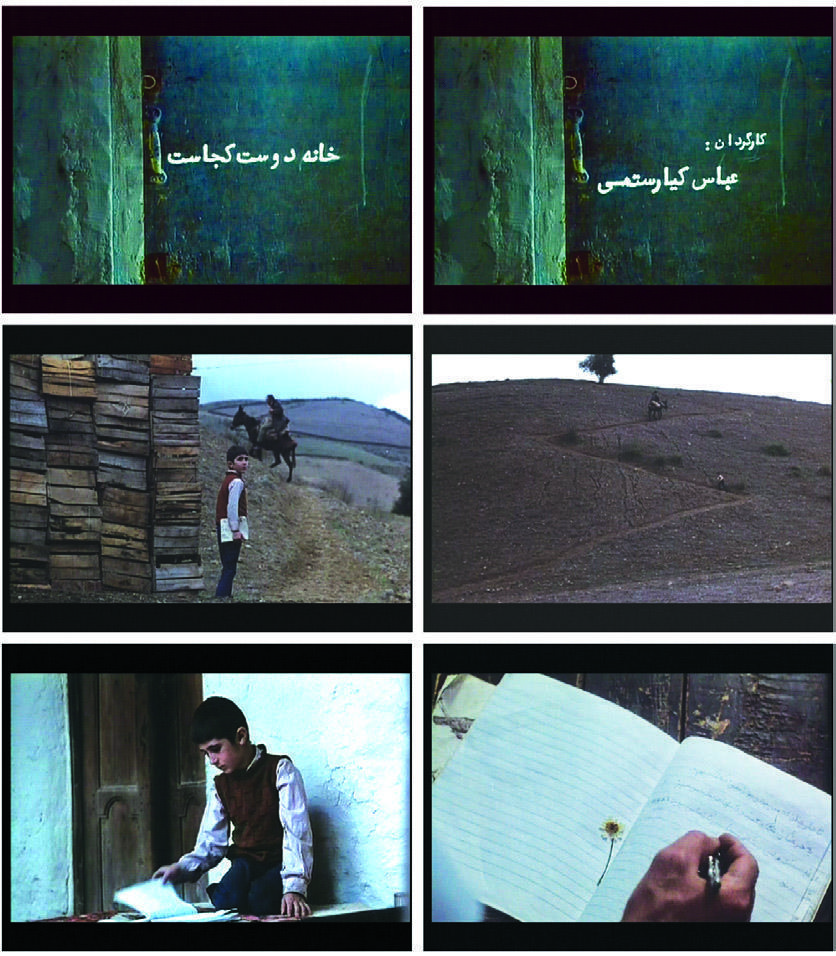

FM: In 1969, Firooz moved to Kanoon completely and took his colleagues with him, launching a research department, a publishing department, and, upon Kiarostami’s suggestion, a film and animation department. Firooz directed all three, and in 1970, Kanoon’s first short motion picture Nan-o-Kooche (Bread and Alley), directed by Kiarostami, was produced.

[Shot in black and white, the film tells the story of a little boy walking home with a loaf of bread, who is confronted by a hungry dog. In the end, the two get over their mutual suspicions and become fast friends.]

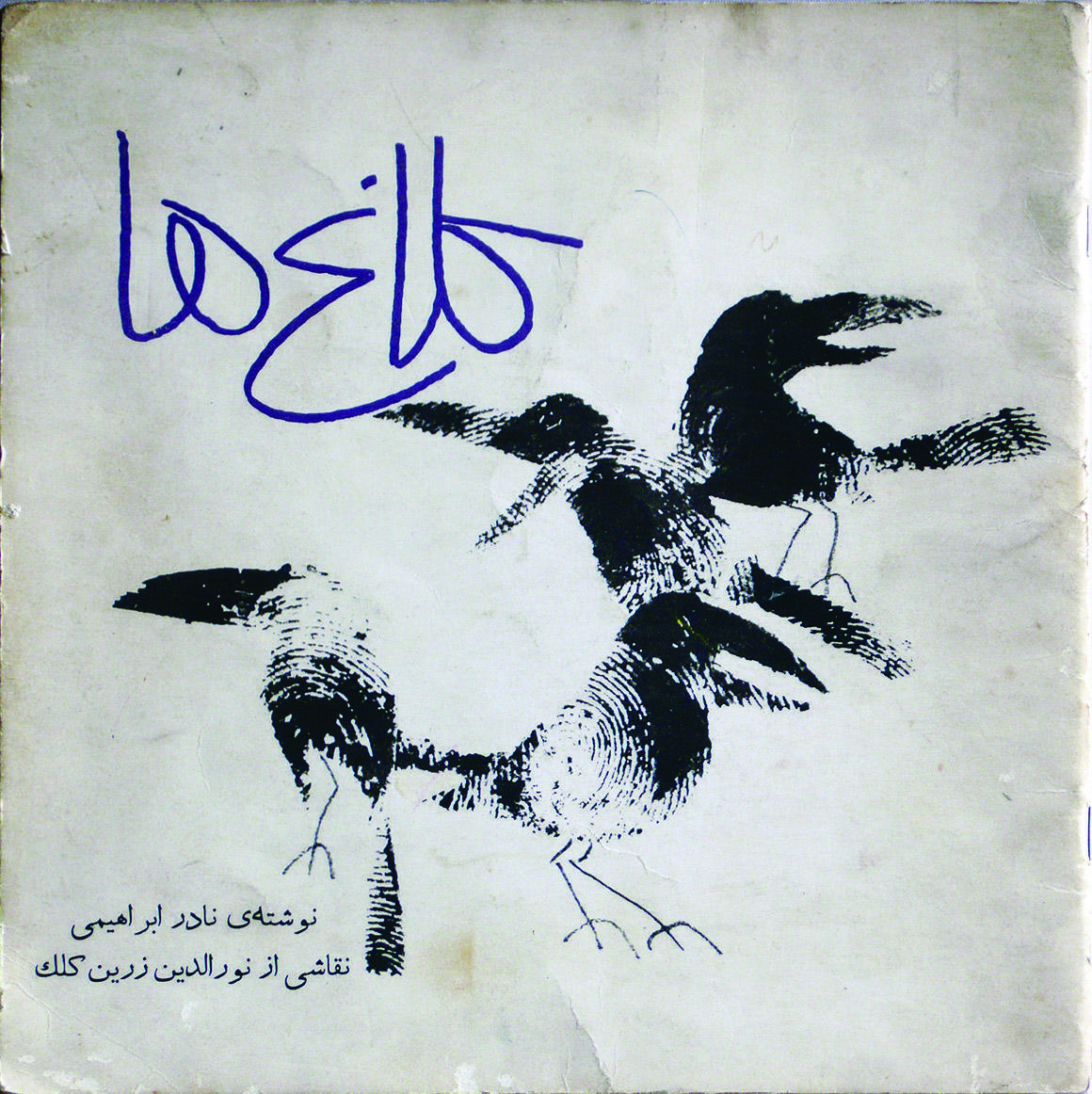

In that same period, the first animations were born, including Agha-ye Hayoola (Mr Monster), created by myself, and Vorood Mamnoo (No Entrance) by Arapik Baghdasarian. With the arrival of Ali Akbar Sadeghi in 1970 and the illustration of Pahlavan-e Pahlavanan by Nader Ebrahimi, and a host of international awards that this book brought for Kanoon, the institution gained more currency and, because of that, more support from the queen.

[Pahlevan-e Pahlevanan is the story of a grand champion named Pooriya-ye-Vali who hears of a younger champion who hopes to triumph over him. The young pahlevan (champion) comes from Sistan to Kharazm to wrestle with Pooriya-ye Vali. His mother accompanies him and prays for him every day prior to the fight. Pooriya hears her, but nevertheless, decides to fight his best fight. He loses to the young champion and leaves his hometown forever.]

Kanoon eventually launched the Tehran Children and Young Adults Film Festival. They were especially interested in Eastern Europe films, like those of Raoul Servais and Jan Oonk. Kanoon hardly let any commercial or empty American films enter the collection.

[Later, that very collection would be the fuel for the post-revolutionary media to broadcast un-American films with educational and cultural values far removed from ostensibly Western or capitalist ideas.]

With the establishment of the film department and the launch of the Tehran festival, Kanoon started to grow rapidly. Many young artists and writers flooded there to make films. Among them were Dariush Mehrjui, Bahram Bezaie, Amir Naderi, Nasser Taghvai, Ali Akbar Sadeghi, Nafiseh Riyahi, Ebrahim Forouzesh, Nader Ebrahimi, Ahmadreza Ahmadi, Cyrus Tahbaz, and even musicians like Majid Entezami, Esmaiel Monfaredzadeh, Hossein Alizadeh, and Sheyda Gharachedaghi. Production increased dramatically.

AS: What year was that?

FM: I’m not sure of the year exactly, but I think it was around 1970, 1971.

Firooz was finally fired from Kanoon at the end of 1972. He had brought one too many leftists to the organization, like Mehdi Samakar and Dr. Rasoul Nafisi, to work as writers and researchers. SAVAK (the Shah’s intelligence services) had always had problems with the leftists, but for the most part Lili had been able to handle them because of her close relations with the palace. But slowly things changed.

When Firooz had to leave Kanoon, the so-called dissident products inspired by leftists were removed. He went on to direct the Niavaran Cultural Centre. But we owe him a great debt for giving us all a start.

AAS: That was our golden age. We won many prizes from all over the world.

[Firooz Shirvanloo would go on to work for Empress Farah Diba’s office, and played a large role in amassing the state’s modern art collection under the patronage of the empress herself. That collection continues to be known as one of the best modern art collections outside of the West, with its Warhols, Hockneys, Pollocks, and beyond. To this day, it inspires a conspiracy theory or two in reference to what became of the works after the revolution of 1979, and that revolution’s insistence on eliminating all traces of Western culture.]

AS: Can you tell me about the libraries Kanoon founded and ran?

FM: Over the course of ten years, Kanoon built 150 libraries in cities and villages throughout Iran. We created mobile libraries to roam to distant villages and distribute books to the country’s nomads. If there were places the buses couldn’t reach, books were sent to children on the back of donkeys and horses. One can say that Kanoon was playing the role of an independent Ministry of Culture.

AS: How did Kanoon raise money and gain support?

FM: From the beginning, a board of trustees was formed and the queen was in charge of it. Its members were from the Ministry of Art and Culture, the Ministry of Education, the national airline (Iran Air), the Interior Ministry, the Oil Ministry, the Pahlavi Foundation, National Radio and Television, as well as nine major national and cultural figures.

Board members supported Kanoon through their affiliated organizations. For instance, Iran Air was obliged to give children Kanoon products as in-flight souvenirs, or the Oil Ministry would give Kanoon products to the children of the employees. Iranian painters painted for children, Iranian sculptors designed toys, the musicians played at events, and filmmakers were dedicated to making children’s works. Back then, Kanoon’s libraries were the best in the Middle East, and maybe even the world.

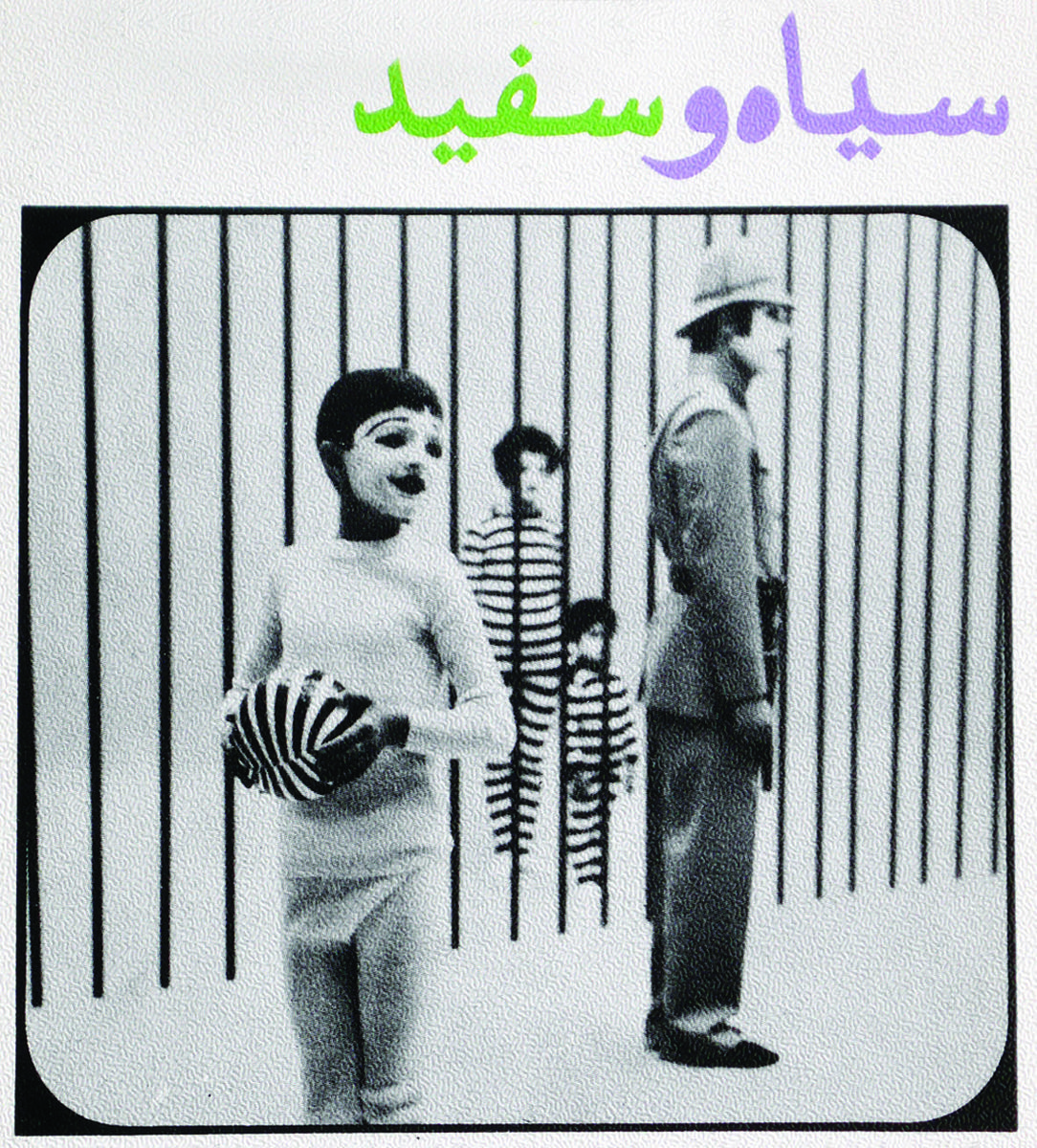

The libraries were quickly turned into cultural centers and started to attract children with free books, films, and theater. Children were crazy for Kanoon. There were weekly classes of painting, filmmaking, writing, music, theater, languages, and ceramics at Kanoon’s various centers and libraries.

Around three hundred libraries were active. The mobile libraries were also mobile cinemas and showed films for nomad children or children living in distant villages. By 1979, one million children were members of Kanoon. At least eight million children were touched by Kanoon products, and the books they published numbered over fifteen thousand.

We published all kinds of books, from religious tales about Shia imams to stories about ancient Persian heroes to fantasy and modern stories. Kanoon’s productions took account of all the people of Iran, from north to south, east to west, as well as the capital. There really was nothing else like it.