Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Sfeir-Semler, Beirut

Beirut

In the Middle of the Middle

Sfeir-Semler Gallery

November 19, 2008-March 21, 2009

Catherine David’s reputation preceded her. No one expected the curator responsible for the political edition of Documenta or the exhaustively discussed, but never presented outside of Europe, Contemporary Arab Representations project, to arrive in Beirut with an exhibition of artworks from the region that were sensual and seductive as opposed to cold and critical.

With its enigmatic title, so much like a riddle, ‘In the Middle of the Middle’ was the first show curated by David to be conceived for and exhibited in an art space in the region. In the past she’d gathered works, positions, authors — she chooses her nouns carefully — and shown them elsewhere, provoking endless debates on issues of geographic representation and art’s ability to travel or translate. This time around she shared her research with a public that lives in, or at least closer to, the sites of her fieldwork.

The truth is that actual traffic in and discourse about art between cities of the Arab world is less common than it should be. This is due to the cost of travel, the time required for obtaining visas, the hassle of crossing borders, the insularity of urban art scenes, and the abject failure of local publications to reach beyond the immediate milieus of their readers. ‘In the Middle of the Middle’ was, as a result, full of surprises, even revelations. And it begged the question: What, really, do Beirutis know about artists who live and work in Cairo, Damascus, Ramallah, or Jerusalem’s Shofat refugee camp?

Whether or not the show was tailored to accommodate the fact that the art space in question, Galerie Sfeir-Semler, is a commercial enterprise — with imperatives to sell rather than simply display work — mattered little in the end. With ‘In the Middle of the Middle,’ David pulled off an exhibition that thwarted expectations, having keenly internalized the artistic strategy that characterizes the artists she champions most: the refusal to use artistic practices to offer straightforward information, reduce the history of violent conflicts to digestible bits, or package geopolitical contexts as easily legible. There was some debate around the opening of the exhibition as to whether the gallery, or the curator, should have been kinder to the audience by offering more explanatory wall texts.

This in and of itself was arguably the intellectual undercurrent of the show, challenging viewers to consider what they want from art and how they respond to material they don’t already know. It was an exhibition that elicited gut reactions rather than intellectual justifications.

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Sfeir-Semler, Beirut

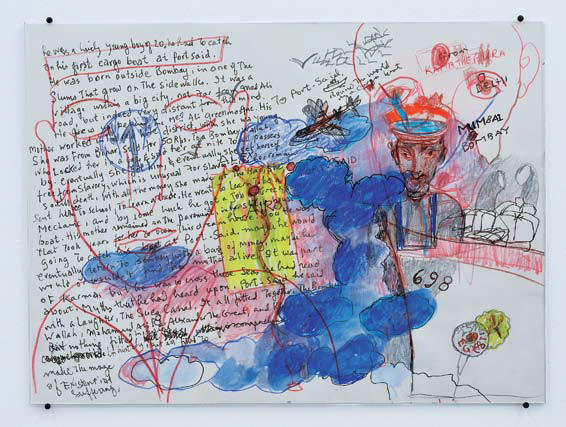

Was it a perfect show? No, and the spatial layout was the most palpable weakness. ‘In the Middle of the Middle’ featured the work of twelve artists working in various media, and the hugeness of Galerie Sfeir-Semler nearly swallowed some of the pieces whole. The Beirut-based painter Ayman Baalbaki, coming off a much better and more substantial solo exhibition at the Agial Art Gallery, was probably the most ill-served by the space. The strength of his piece Ya Abati, from 2008 — of kafiyyeh-clad fedayeen on a vegetable seller’s cart, transformed into a Byzantine-style triptych covered in gold and embellished in lights arranged like the Big Dipper — was lost on the wall. Two gorgeous series of works on paper by the Cairo-based Anna Boghiguian were unduly separated and somewhat unmoored. Those works — one honoring the Greek poet Constantine Cavafy, who is rivaled by none in his sad, sensual verses capturing the decline and decay of Alexandria, the city of his birth; the other a string of self-portraits depicting an enormous, spectral woman looming over, entering, and then defecating on Cairo’s City of the Dead — demanded intimate engagements. They were at once tender and delicate and explosive and uproarious. They deserved a shrine more than an expanse of bland white wall.

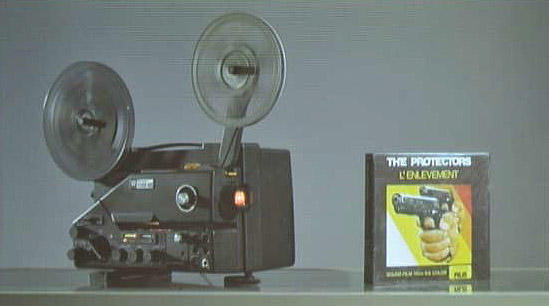

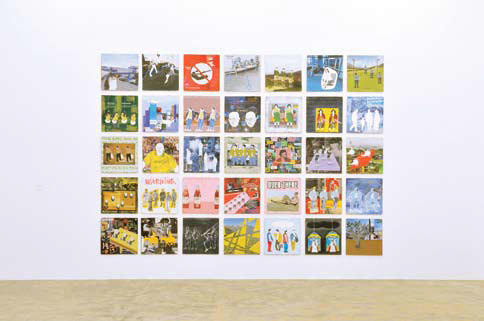

Better suited to the venue was Wafa Hourani’s madly obsessive and monumental replica of the Qalandia refugee camp, fast-forwarded to 2048 and the centenary commemoration of the creation of the Israeli state. Essentially an amplified diorama, replete with gold fishbowl and a series of television antennae shaped into fey dancing wire sculptures, the piece held its own by molding an entire world, insanely detailed and craftily jerry-rigged. Among the totally tactile and formally seductive works were Simon Kabboush’s oil paintings of Damascene teenagers and Hani Rashid’s wall-size grid paintings on cardboard; both their works were slightly larger than, but similar in style to, old-school album covers and depicted bursts of street-savvy pop culture that simultaneously obscured and revealed a vocabulary of social, economic, and political anxiety. Akram Zaatari’s subtly humorous video, L’Enlèvement, part of his ongoing Hashem El Madani Project and an intriguing consideration of the image, felt slightly out of place here, as did Walid Sadek’s beguiling Death and the Sun (What my father sees, most probably), with two trumpet mouthpieces jammed into a wall like eyes in a vacant stare.

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Sfeir-Semler, Beirut

The biggest, but least surprising, disappointment was Waël Noureddine’s A film far beyond a god, a title that would have been so much better without that last indefinite article. When an earlier film of Noureddine’s, Ça Sera Beau (from Beyrouth with Love), started making the rounds in Beirut in 2005, it was thrilling in no small part because some of the city’s many film festivals were enthralled with it but terrified to screen it. Shot on 16 millimeter, it was also a lush, concise, and accomplished work. Everything Noureddine has produced since, however, has wallowed in self-indulgent nihilism. A film far beyond a god, with its tedious rock-star badness, its evocation of “Che Guevara and Co.,” its convoluted socioreligious critique, and its scenes of the artist with camera and gun, was unfortunately more of the same.