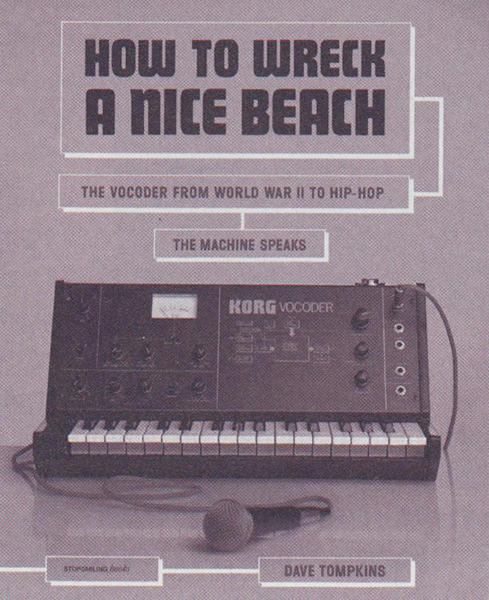

How to Wreck a Nice Beach

By Dave Tompkins

Stop Smiling Books / Melville House, 2010

How did the Bee Gees hijack Edison? How did Winston Churchill contribute to Michael Jackson’s “P.Y.T.”? How did the robot become a Top-40 stalwart?

The answer lies in the vocoder, the voice-altering machine that might have changed cryptology, but ended up changing pop music instead. Like many miracles of modern science, the story of the vocoder begins with the Pentagon. Namely, with the National Security Agency, where the most delicious of conspiracies are concocted — this one being filed under The Start of the Digital Revolution: SIGSALY Secure Digital Voice Communications in World War II. The means by which Afrika Bambaataa converted German electro into Manhattan block parties was developed as a means of distorting the voices of world leaders, transmitting the aural fragments to machines specially designed to reconstruct them as “an electronic impression of human speech,” Dave Tompkins writes, “a machine’s idea of the voice as imagined by phonetic engineers. Not speech, they qualified, but a ‘spectral description of it.’” Funk came to the Bronx via secret telephony.

Tompkins tells us, in his scattershot narration of the many disparate lives of the vocoder, how one of the government’s many promising, expensive, and abandoned tools of dissimulation eventually came to dominate our airwaves. While the Pentagon came to own the technology, it originally emerged in 1928 as a walk-in closet of primitive computers at the offices of Bell Labs. From there it made its way to Kraftwerk, Winston Churchill, Ray Bradbury, Wendy Carlos, John F. Kennedy, and Battlestar Galactica, among others.

Tompkins has tracked down each of those others, it seems, and mapped their connections, and parsed the significance — or the uncanniness, or the sheer unlikelihood — of the fraternity they’ve achieved through using this machine. His ability to piece all this into a compelling constellation, and his skill for juxtaposing fragments of narrative and bits of historical data in the service of a greater, if diffuse, narrative, seem preternatural. How to Wreck a Nice Beach — the title is a reference to a misunderstanding of a phrase rendered by the vocoder, “how to recognize speech” — reads like a kind of Guns, Germs, and Steel for music nerds and, more broadly, for believers in the interconnectedness of all things. I came away from reading this book thinking that when a butterfly flaps its wings in Arlington, Virginia, it must eventually produce a chorus of androids on wax in the Bronx.