“We can recycle anything,” says Shabbir Pasha, sitting at his desk in a small concrete hut in Bangalore, India. “We even recycled the World Trade Center.”

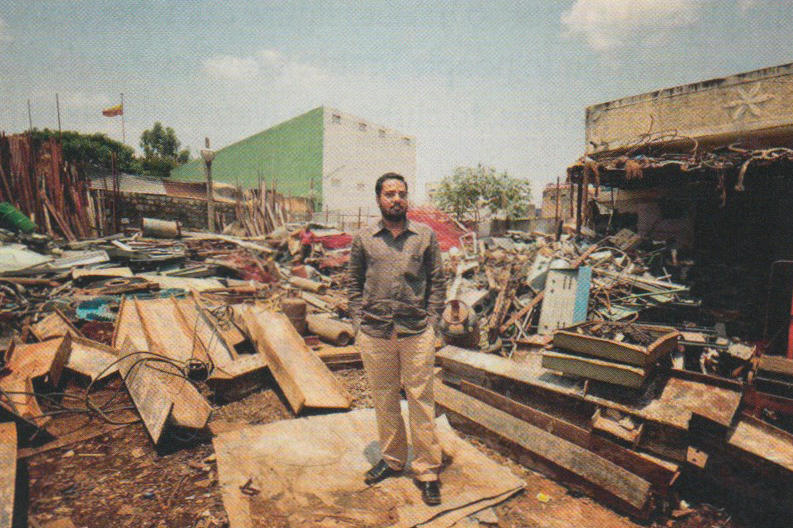

Pasha’s office lies in the corner of a metal scrap yard piled high with old pump sets, girders, air conditioners, and wiring. “We received almost 500 tons of square-plate steel, copper, and lead from the rubble of the World Trade Center,” he tells me. “It was processed in Mysore and Bangalore, at yards like this. We separated what was useful, all by hand.”

It’s impossible not to wonder where the remains of the Twin Towers are, amid the piles upon piles of scrap. A small group of men laboring under a tarpaulin will soon pick and chip at the piles with their hammers and pliers. They will separate bits of metal from casings and other material, then pass the metal on to be sold to foundries, where it will be melted into ingots, rods, and billets, most of which are consumed by the local market.

Pasha buys most of his scrap from demolitionists, auctions, and scavengers. “A lot of scrap from Germany is shipped to India,” he says, “because they can’t separate the stuff there. It’s too expensive for them.

“We’ve run this business since 1970,” he says. “My father started it. We get scrap, and my boys separate it. They’re paid about a hundred rupees a day.” The price of scrap fluctuates based on demand, and during the recession demand has dropped. “The best time ever, business-wise, was during the Beijing Olympics.”

Did any of the World Trade Center end up in Beijing?

“Definitely,” he tells me. “There was huge demand for steel, as China needed it to build hundreds of buildings for the Olympics.”

Business is not as good as it once was. “But we are okay,” Pasha says. “The local market is still not bad for steel: we get about eighteen rupees a kilo. For copper we get 350 rupees a kilogram. It’s a good business.”

I ask Pasha where his salvaged metal ends up. He waves his hands expansively. “All around Bangalore. In building pillars, in cars, in electrical fittings. Many of our houses and buildings come from here.” How did he feel about recycling the World Trade Center? Pasha thinks for a couple of seconds. He says he got twenty rupees per kilo of steel for that batch, which is better than the eighteen rupees he gets today due to the recession.

“No,” I say, “how do you feel about having processed the World Trade Center?”

Pasha looks at me, slightly confused. “It felt good to get twenty rupees a kilo for that steel. It’s not as good as some other times, when we got twenty-nine rupees — like during the Beijing Olympics — but it wasn’t bad.”