“There are no amateurs in the world of children.”

— Don Delillo, White Noise

Child actors are often unsettling, especially to the grown or the childless. Good acting has undertones of magic, mimesis allowing us mere mortals to momentarily embody powers usually reserved for the divine or the demonic. For a child to act with any particular skill inspires first praise and then concern that we might be witnessing an intervention by outside forces. Even found in a presumed state of nature, playing cops and robbers in a field, or applying mother’s makeup in a bathroom and teetering in her heels, an acting child implicitly honors the nearest adult before assaulting him or her with caricatures and satires. If we look long enough, we start to see things in a child’s pantomime that compel us to cut the scene short before they see them, too.

In Rainer Maria Rilke’s “Eighth Duino Elegy,” what children may or may not see aligns them with animals. The poet laments that we civilize our wild children by teaching them to fix their eyes on things and shapes, to their — and our — diminishment. In one translation, young eyes are yoked to “structure,” in another to “what is settled.” Either way the familial scene he describes is a common one, in which acculturation and coercion are indistinguishable. A child’s eyes are remade as “traps for freedom”: “turned back upon / themselves, [the eyes] encircle and / seek to snare the world.” Once this work is done, it is only in the “faces of the beasts” that we can ever hope to see reflected “what truly is,” the warm-blooded creatures of the earth gazing unnervingly “into openness with all / [their] eyes.” The next best thing, of course, is poetry, a form of play.

Alongside poets, children, and beasts, Rilke sings the virtues of the angels, who have their own ways of seeing the world as it is. But the angels he has in mind are not rose-cheeked cherubim with their harps and tiny wings. Rather, as he insisted in a letter to his Polish translator, they were the immanent, immaterial angels of Islam, which Rilke had likely discovered during his travels with Lou Andreas-Salomé and her husband, the Orientalist Friedrich Carl Andreas. The angels of Islam, in this account, are invisible, omnipresent beings made of light and structurally incapable of disobedience. They submit to the Almighty perfectly because they are unburdened by any sense of separation from their Creator. (Paradoxically, this is what makes angels inferior to men, since humans choose to submit. It is also what distinguishes them from the jinn, God’s first creations, whose leader, Iblees, chose freely to rebel.)

In Rilke’s imagining the child sits cross-legged, somewhere between angel and jinn, enjoined by her elders to focus on what is settled and good in order to forestall subversive potentialities. If creation is a predestined drama, Rilke’s children must be the most unreliable actors ever to walk its stage. We are called upon to teach them their scripts not just because their fudged and forgotten lines are an affront to what is, but because we fear what such lapses in character might inadvertently reveal. The poet cherishes these illuminating improvisations—but then again, he is already halfway to the dark side and perhaps not to be trusted. For those without poetic temperament, there is only a creeping, parental dread and the long anxious wait for our children to join us in settled adulthood.

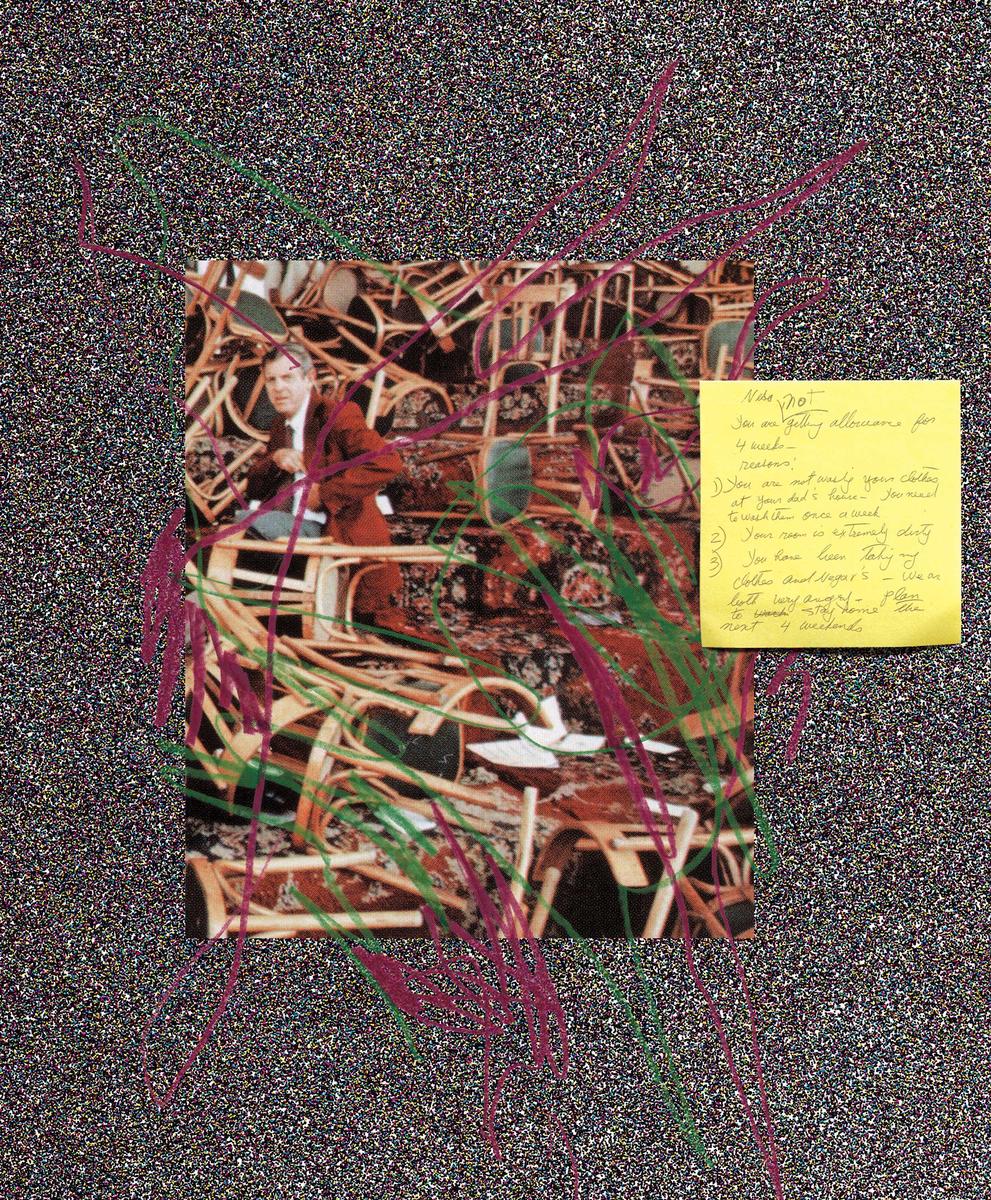

In Wael Shawky’s Telematch series, the Egyptian-born artist revisits a German game show originally broadcast and widely syndicated during the 1970s. The residents of two Teutonic hamlets would vie for prizes and for the laughter of the audience by running a gamut of races and obstacle courses, their bodies clownishly handicapped by elaborate costumes, equal parts cartoon and fairy tale: full-blown Disney characters; giant ladybugs; elves; camel-riding sheiks, their mounts a riot of felt and foam; and the occasional Egyptian pharaoh, ten feet tall and precariously seated on his throne. Shawky’s still unfolding project — its constituent pieces have been aggregated and disaggregated over the last few years in installations and individual projects such as Telematch Upper Egypt, Telematch Suburb (on view at SITE Santa Fe’s biennial until January 4, 2009), Telematch Sadat, Telematch Supermarket, and Telematch Shelter — now inverts and transposes the logic of its nominal source material. Instead of German adults racing to beat the clock while weighed down by the ridiculous regalia of mass-marketed childhood fantasy, Shawky puts children from the upper-Nile city of Asyut through oblique paces, dressing them up in the invisible regalia and scripts of history and culture.

In Telematch Supermarket, a line of children driving pedal-powered cars and trucks makes a solemn procession through the tight aisles of a dimly lit supermarket. The vehicles seem handmade, the product of an exceptionally clever rural craftsman who has welded bicycle gears to skeletal metal frames and fashioned chassis from cardboard and stray pieces of wood. The convoy itself is a roving tableau of urban irritants and vexations. The road is too narrow, and at any given moment a few of the pint-sized drivers threaten to careen in slow motion into stacks of canned goods and piled sacks of flour. The boys behind the wheel display alternating flashes of boredom, anxiety, and anger. One of them, keenly aware of the camera Shawky has placed just outside his metaphorical windshield, hunkers down behind the wheel as if enduring some all-important driver’s test, while another, warming to a different role, leans out his cardboard cut-out driver’s side window to shout at the slowpokes ahead. (The only sound in the audio is a gathering synthesized hum, but one can almost hear the boy shouting, “Peasant!”) The girls, passengers all, sit in the front or hunch in the back of makeshift pick-ups and wait.

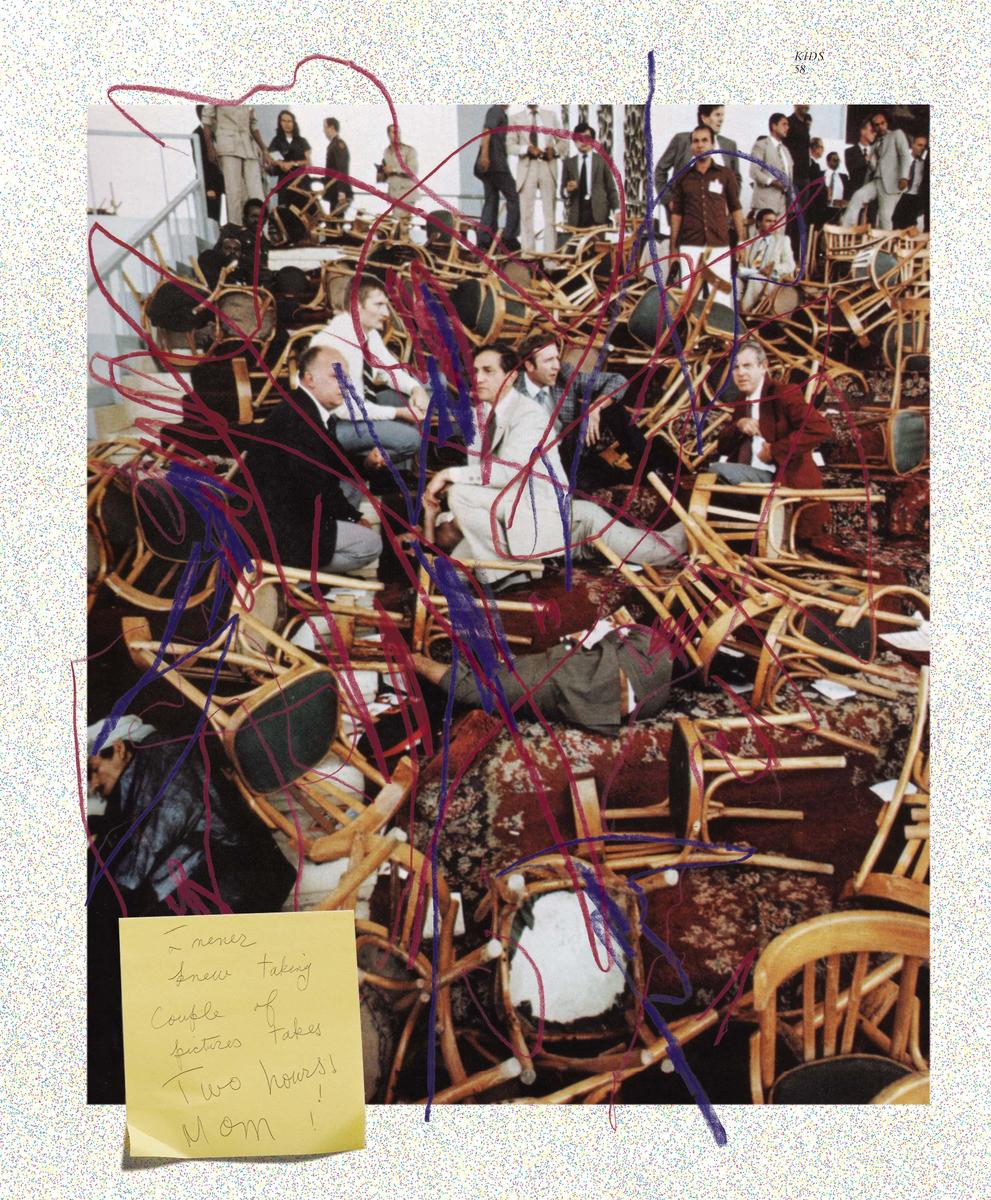

Supermarket follows Shawky’s most famous work, Telematch Sadat, which prominently features another child-driven convoy. In this video, the children of Asyut reenact first Anwar Sadat’s 1981 assassination, then his funeral. In the opening section, a line of the artist’s makeshift pedal-trucks moves toward the camera on a bright dusty road before unloading a handful of boys, toy guns in hand, their faces obscured by masks and hoods. Shawky’s camera goes handheld and jittery as some of the boys fire at Sadat, offscreen, in upright, exposed positions, while others run to and fro and shoot haphazardly. The gap between their jerky movements and the precise choreography of movie shootouts lends the episode a particularly disturbing realism. As in the video of Sadat’s actual assassination (readily available on the web, along with many episodes of the original German Telematch), the leader himself is an unseen center of attention; he makes only a partial appearance in the second half of Telematch Sadat. Once the shooting is done, a crowd of blue-shirted boys carries a simple, wooden box toward a pint-sized approximation of Sadat’s pyramidal tomb, an object of stark, clean sculptural simplicity that makes a ringing counterpoint to Shawky’s jury-rigged cars. Dozens of boys stumble and jostle for position, and when they finally make their way to the tomb, they move the casket into position in waves of disarray and recovery. Individual boys find diametrically opposed ways to stand out from the larger mass, calling attention to themselves either by taking charge and moving the casket forward or by standing back and watching, shooting furtive glances into the lens.

Politically engaged reenactments of historical events are in vogue these days, but Shawky’s Sadat is notably oblique. Unlike Mark Tribe’s excellent Port Huron Project, where dozens of speeches from the American civil rights and Vietnam eras are energetically performed by groups of actors (right down to extras planted in the audience to respond on cue), the Sadat snuff film is almost a pretext. Shawky’s true subject hangs just out of reach, in the jumble of free play and coercion Rilke identified with childhood. This contest of control and play gives Sadat a familial relationship to Oliver Stone’s W, where the horrific eight-year presidency of the arrested boy-king George W Bush is also a kind of pretext. W is at best a savvy treatise on the art of high-end impersonation, from the actors’ impersonations of their real-life characters to Bush’s impersonation of a president. Ernst Gombrich’s 1938 essay, “The Principles of Caricature,” could easily have been written about it:

Caricature has its strongest effect in reduction, in formulae…. [A] single feature often stands for the whole, and a person is represented by one salient characteristic only. To the caricaturist, however, this extreme simplification is not the starting-point of his work. He arrives there often by stages, beginning with a life-like portrait which he somehow simplifies and distorts in the absence of the model.

The skill of W’s caricature is its fatal flaw, its performances substituting for interpretation and analysis, the absent model of Gombrich’s formulation. Shawky’s videos, on the other hand, never slide into caricature. His children play themselves even when driving trucks or shooting guns. There is no absent model for child actors to evoke; they are the thing itself.

If Shawky has an ideology, it is the potentially uncool (especially for the career of a globetrotting conceptual artist) notion that the kids are — surprise, surprise — all right. For his Telematch Suburb installation, Shawky positions a couch in the center of a gallery space while three seemingly unstaged childhood moments are projected on the walls around it. There is no tragedy or outsize drama, just slices of primal everydayness. In the central video, a short loop depicts dozens of children entering and exiting a short but improbably roomy desert tower. The rough-hewn structure’s unseen interior is clown car, termite hill, and magic wardrobe wrapped into one, the line of kids appearing and disappearing in steady cycles that have the regularity of a relaxed daily commute, a continuous chain of care and mutuality, older children pausing mid-screen to extend a hand toward younger ones, the littlest scurrying to catch up.

To the right, an LCD screen shows an Egyptian teacher gamely delivering an English lesson to his young charges. He seems an able enough tutor, but the more fully bilingual viewer might laugh (or wince, as the case may be) at the thought of these students carrying their teacher’s thick accent out into the world with them, to treasure or overcome at their discretion. To the left, a wall-size projection of a heavy metal band provides instruction in post-adolescent attitude. Rangy young men, bald heads banging, phallic guitars swinging, are on a stage in the middle of field, while rural townspeople mill about and watch, by turns bored and amused. A donkey’s spasmodic twitching almost seems to keep time. Instead of cultural conflict or dire ruminations on tradition and modernity, there is the kind of comfortable mutual disinterest that only a family can muster.

One comment on YouTube, a reaction to one of the many Telematch Germany videos available there, says, “I used to watch it as a child in Singapore and it was a time for local families across the island to gather around their TV sets. I wish I knew the name of the commentator. He had a fantastic voice that I remember even today! The games and his commentaries always emphasized how friendly games bring people together. I got to know Germany & her people through this programme.” This is clearly Shawky’s point of departure: cultural parallel lines converging at a global media horizon. But his project is at once riskier and more fundamental than the German show’s heartfelt presentation. Like all motion pictures, Shawky’s artworks are a compendium of ways to trap the bodies and eyes on both sides of the screen—from the formal construction of his installations and videos, with their predetermined lines of sight, to the plight of his child actors with their loose but overdetermined performances. The degree of their eye contact with the camera serves as an index of their submission, disobedience, or subversion. Follow his script or don’t; attend to your role or ignore it; move the coffin or stand and gape at the camera. In the end, it’s all the same.