Gini Alhadeff is a writer, editor, and translator, and the author of The Sun at Midday, a memoir, and Diary of a Djinn, a novel. Hampton Fancher is a writer, producer, and director whose film work includes The Minus Man, The Mighty Quinn, and Blade Runner. They spoke at his Brooklyn home on March 9, 2009. Hampton thought he’d be interviewing Gini, who thought she’d be interviewing Hampton. “That’s fine,” Hampton said. “That’s like being married to dead people.” Afterward, Gini edited herself out of the transcript of their conversation, rearranging sequences while respecting the original wording, turning the whole into a sort of joint work of fiction.

Yeah, I’ve had that kind of fear, sometimes so bad that if I’m driving, I have to stop. One time in Paris I crawled out on my hands and knees because I couldn’t stand up, I was so frightened. I was at the Printemps Department Store, and I was with this woman who was not a maternal woman, she’s not kind in that way at all. And I disappeared because it was happening. I sat down in a corner. She came over and I looked up at her, and she knew. She took my hand and got me out of there. I still think about it. Goddamn, how did she know? To be understood is the consolation. It’s so hard to be understood.

I always thought if I was in a plane crash, I would grab whoever I was next to — an old man, a kid, whoever it was — and I would kiss them. For years I thought that, because I always think I’m gonna crash. And then it happened. They couldn’t land, they said they couldn’t get the landing gear down, they were flying back and forth. They wouldn’t even talk to us. It’s a weird atmosphere that occurs, there’s a silence — it was horrifying. And this woman next to me goes nuts. I talk her down — forty-five minutes — and I’m telling her why we’re going to be fine… I’m perfect for her, I’m telling her all these things, her eyes are fixed on me, and it just keeps going. And finally they say, “We’re going to have to do it — we’re running out of gas.” It was a Washington, DC, to New York flight. They’re coming into La Guardia, and we get into the crash position, and this is it. We’re going to die. And I remember as I was talking to her, I could see the ocean through the window, to the east. Then we pulled up, and I could see Manhattan. I thought to myself, “Don’t go in the buildings,” but what I said was, “It’s nothing, here’s why.” I lied. I told her I knew how to fly these planes, why it was normal, and she was hanging on every word.

Inside I was scared, but outside I was doing this. So we’re coming in and everyone is in the crash position, and I know I’m dead. It was everything I could do not to do two things, honestly: I had this overwhelming need to vomit, and I thought I was going to shit my pants. I was that rollercoaster-scared, and suddenly she grabs me and says, “Kiss me!”

And I couldn’t. She put her mouth on mine. It must have felt like a chicken beak, I couldn’t open my mouth. I thought, “You’re an asshole, Fanchi, saying you’re gonna kiss the person you’re next to when you die!” I was just not there for it. But it all worked out. I mean, we’re alive. When I talked to her later, she wouldn’t believe that I was frightened. She was crying. I was beyond crying.

Actually, that’s the easiest thing to do. You get into situations where you’re in trouble, and if you can help somebody else — it’s an old acting trick, really — you’re okay.

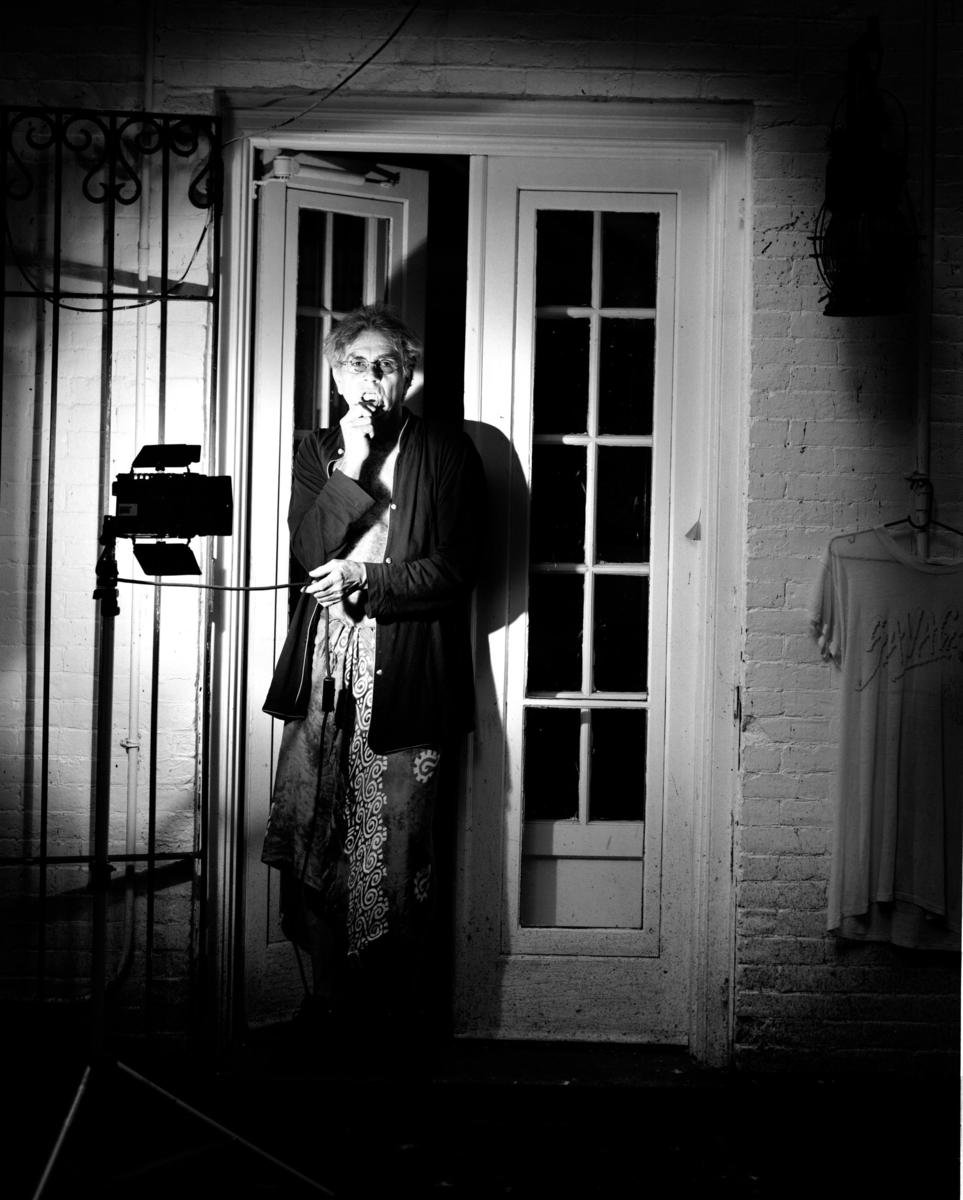

I’m curious about people who believe things. Updike was Episcopalian, and he said, “I couldn’t live without it.” And Anthony Burgess, Graham Greene, John Donne. I can’t quite understand it, the need for it. I was raised by Catholic nuns till I was six, and I believed those things till I was six and a half and then really got rid of it by the time I was nine or ten. Not because I was precocious, but just because I was primitive. I am going to change clothes. I don’t like to have clothes on in the house. I don’t usually wear the Chinese jacket — that’s out of deference to you — I don’t want you to see my ugly, goat-like body. I wasn’t brought up to wear clothes in the house, and as soon as I walk in the door, I take my clothes off.

We were a pretty naked family — I had a sister, a father, and a mother, and we weren’t nudists, but nobody seemed to pay much attention to clothes, I mean wearing them, when we were in the house. Sometimes it embarrassed me, actually. My mother wore no underwear, and she was very extravagant with her body. She loved dancing. Probably that’s why I became a dancer, because of her.

I started dancing when I was very young. I just had a proclivity for it, from when I was six or seven years old. And there was a woman I really loved when I was a child, Milada Mladova. She was a premiere dancer. She was around the house, and they would all listen to music and dance, and my sister became a dancer. So I was dancing, I was interpreting. You know how kids play games? I would make up dances. By the time I was ten or so, I was choreographing things for my sister. And by the time I was thirteen, I was dancing professionally.

I didn’t speak until quite late, and I had my own language for a long time. I didn’t go to school, I couldn’t say the ABCs, I’m dyslexic and all that, but I was interested in languages. As a child I was fascinated by words; they used to call me the little lawyer in the family. My mother’s Mexican — do you mind if I smoke? — but she didn’t speak Spanish until she moved to Mexico. My parents moved there in the ’50s, and her accent was like a gringo’s. I spoke Spanish as a child because I lived with my mother’s aunts from the ages of three to six in East LA, the Mexican part of Los Angeles, the Barrio. They were Indians, basically. My great-grandmother was a full-blooded Yaqui Indian. She was from the border… puro India. Nina Ornales. Scared me to death. I was horrified of her.

Here’s my father when he was twenty-two. And my mother when she was sixteen. You can see the Mexican there. Yeah, she was beautiful. She used to laugh at herself because she was so beautiful, all the time I was growing up, and then she became a little old lady, and it was amazing to her — I mean, I know the feeling, I have it myself right now. She couldn’t stop laughing at the idea that she’d turned into her parents. She was five-foot-eight and regal, she looked like Ava Gardner, and then she turned into a little Mexican woman, and she would laugh so hard, there were tears in her eyes. I’m not like that. I mean, it’s funny, but I take it more seriously. I hate it.

Was I good-looking? I heard that all my life. Women, people, magazines — all that stuff. I used to eat that up. I’d pretend I was asleep just to hear my mother and her girlfriends talk about me. It’s one of the foundations that you build your life on without even knowing it. And then when people stop looking at you across the room, you are aware of it, I think. You can’t have it any other way, so you have to enjoy it — the adventure, the drama, the self-drama of it, the novel of it, as in the story of your life. Because you never expect it to happen.

I never thought I would live long enough to get old. I just never considered it.

Recently someone asked me my definition of beauty, and this sounds maudlin, but I think it’s just a fact: it’s when the child remains in the face. I know people who are so beautiful, it makes me want to cry, and someone else thinks, “Oh, they can’t be a movie star — they’re not beautiful enough.” And they’re so much more beautiful than any movie star. I mean, beauty: I’m talking Botticelli. And it’s because that vitality remains.

My sister and my mother, they used to dress me up. They’d curl my hair, put makeup on me. It was all fine, kid games, and I liked it. Probably I liked the attention. My father must have been horrified. But really, I was only encouraged at home. I mean, I had some sense, when I became a dancer, that my father wished I had become a marine. But he would come and see me dance and seemed to be quite pleased at people applauding his son.

My father was very masculine. He was a boxer. I box — I mean, I just hit the speed bag. But I was brought up going to boxing places. I met a guy a few years ago, and he said he boxed at the Upper West Side Y, and I said I’d like to do that, too. So I joined, and there was a trainer that was there. His name was Spider, and he was an old killer. No, literally, he was a mafia guy who had retired and was working at the Y. I liked to talk to him and tried to make friends with him, and it was hard. He was an enforcer, so I asked him what he did. “Well, you know, they would fly me down to Miami to collect debts.”

I said, “Did you ever get on anybody, you know, like that?”

“No, you try not to do that,” he said. “They don’t like that.”

“But you did it anyway, right?”

Then I asked him, “Did you ever kill anybody?”

And he said, “Don’t talk to me about that.” Of course he has. So we boxed, and he’s much older than me, and he’s a real fighter, and I’m not a real boxer. And when you get hit by somebody, it brings out something primitive. He was hitting me and I wanted to cry, and I couldn’t stop laughing. I’d be up against the ropes, and he would be like, Bam, Bam! It made me giddy, like hysterical, and I couldn’t stop laughing. The thing is, you don’t want to hit anyone in the face, because of the helmet, it’s a no-no. You’re only supposed to do body punches. And he kept yelling at me, “Come on, Fancha!” — he called me Fancha. He said, “You got a great jab, use it!” He kept yelling at me, and I threw my jab, and I got him right in the face, and it was the wrong thing to do. I felt terrible. There were people watching, and they looked at him and said, “Just finish him! He knows the accent but he don’t speak the language!” I liked that, he knows the accent but doesn’t speak the language.

But I do like boxing. I like to do it. I love Muhammad Ali, that Dutch woman… she’s half black, half white. There’s a film you should see, Shadow Boxers. It’s about three female boxers. The others aren’t interesting, but she’s fascinating, the Dutch girl. I was hitting the speed bag one time, and the guys who were in there — Dominicans, Cubans — they don’t like me, they’re talking, and I’m really self-conscious of them. And then suddenly they stopped. I looked to see what happened, and there’s this 5’3” girl, and she comes in and looks around. And I was like, “What’s wrong with you guys? Are you guys shy? What’s happening here?”

And they said, “She’s golden gloves, she’s a champ.” And I went up to her and I asked her, “You’re a champion boxer?” And she stood there, real shy, and she said quietly, “Yeah.” And I talked to her for a while — they were very respectful of her — and I asked her, “How did you start?” And she said she was from Harlem and had a lot of brothers. So then I said, did you see that film? And she said, “Yeah,” and she names that Dutch girl, and she said, “I just fought her.” She said she knocked her out in the second round.

The next time I’m in the gym, there’s a retired cop who I box with sometimes, and I ask him if he knows that girl, and he says he does. “What’s the story with that girl?” I asked. And he gave it to me…

“So I’m on the subway and there was a sketch of this guy — you know the ones that say WANTED, and there’s one on the subway at my stop. This guy had been ravaging people in the subway — big black guy — he would beat people up and rape them and steal from them, and they had been looking for him for a year. So she’s sitting on the subway, sitting in the first seat in the first car going home, going to Harlem, reading a magazine, with the golden gloves that she won around her neck. And this guy, who’s 6’4” and 250 pounds, is walking through the aisle, and he sees them, and he comes up and hits her in the head to grab the gloves — and this is a little girl, 5’3” and 120 pounds, so innocent you’d never look at her twice. And now he’ll be in the hospital for the rest of his life, brain-dead. They figured it must have been seventy times in the head.”

I don’t remember her name.

You know, the most famous boxing gym in the world is here in Dumbo. And I go there two years ago, and I’m standing there talking to the owner, and all of a sudden she comes in with her posse. Immediately he goes over to her. And then I go up to her and say, “I don’t think you remember me,” and she says, “No, I remember you, I remember you.”

A couple of years ago I met someone who hadn’t seen me since I was twelve. She said, “God, you haven’t changed.” I said, “In what way haven’t I changed? Man, I’ve changed.” She said, “No. Everything that you say and do, just the way you move your arms, your legs, the way you look, the way you talk — it’s just the same as when you were twelve years old.” I was astounded by that. And then I thought, “Oh fuck! That’s the same with everybody. We don’t change.” I met a guy in the hallway the other day — he’s this humorless, soulful guy. If I’d met that guy when he was seven years old, he’d be just like now. He’s been to school, he’s become a lawyer, he’s married, he has kids, but I’d be looking into the same soul, those same eyes. He doesn’t know irony, you know? And somebody else I meet, they knew irony when they were seven.

In every society, especially capitalistic society, meritocracy is everything. And it’s terrible. That writer — what’s her name? — that English writer said, “It’s arguable that it’s better for a man to have to pray for rain than scramble for advancement.” She’s, like, a hundred years old, and she’s still feisty… Sybille Bedford! “Better for a man to have to pray for rain than scramble for advancement.” It’s in her book, A Visit to Don Octavio. She’s on the east coast of Mexico in this horrible little village, and there’s a bunch of guys sitting up against the wall on the street, and it’s raining and she’s studying them and she’s looking at them. And she thinks that. It’s a romantic notion in a way, but I like it, it makes sense to me. In fact, it’s not a romantic notion, it’s a fact. I’ve known too many Mexicans, country Mexicans who are so wise, as opposed to some Mexican lawyer in Mexico City or whatever.

Have you read Castaneda’s books at all? The first two are really interesting. That guy Don Juan, he’s one of those Mexicans. Uneducated, brilliant. I lived next door to one down there once. He got me so good.

This guy, he was an Indian, a completely uneducated man — a peasant, a peon, he doesn’t even have a home. I had this little villa on a lake — in fact she wrote about it, Sybille Bedford, it’s right in Xicotepec, on the west end of Chapala. I had rented this place for a few months. And I would see him once in a while; there was some acreage next to me on the waterfront. He had a little hut made out of grass and sticks, and once in a while I’d see him at the water’s edge, and I wondered how he lived, though I didn’t want to get to know him. Someone in the village told me that he was a witch, and that made me curious. Because he was like a little Indian guy, ancient.

One time I saw him digging a hole in the ground to get some water from the lake so that the children there, little ragamuffins, could bathe. I went down to that place with a friend of mine who was visiting. I told my friend, “Here’s my camera, I’m going to talk to him, shoot a picture that you see is interesting.” So I go and I’m talking to him, and he’s very deferential, very humble, soft spoken, not a man of words. And I’m asking him a few questions and Joe, my friend, can’t make the camera work. He’s telling me in English, “I can’t get the camera to work.” I didn’t want to make a big thing about it in front of the old man — Don Jose — so I say, “Let me try it. You talk to him.” I took the camera and it wouldn’t cock. Then the shutter worked — but not when I was pointing it at him. Finally I got it to work, and I said to my friend, “Here, try it.” And Don Jose says to me, “You trying to take a picture of me?”

He was barefoot. “Here, cross this line,” he said. He goes like this, in the sand. So I cross the line, and he says, “Now tell him to take a picture.” Click — it worked.

Then I asked him in Spanish, “Tu eres un brujo, verdad?” You’re a witch, aren’t you?

And he said, “No, I’m not a witch. The witch lives up on the hill, in the jungle. Look what he did to me.” He opened up his shirt, and there was this horrible burn scar across his belly. I don’t believe in witches, but I’m fascinated by this guy. He’s got this warmth, this intelligence on his face. I liked him. So that was that. I would see him once in a while, I’d wave at him, but we don’t talk.

When I got back to civilization, I had the film developed: it was all black. But that’s not the story.

It’s the night I’m leaving, and the whole trip has been a disaster. I was trying to write and it wasn’t working, it didn’t work at all. I had used all the money I had, and it was the last night. I was sitting in front of a Smith-Corona, and I started to cry. I had my face in my hands. I wanted to die; I wanted to kill myself. I’m thinking, I can’t go back to California. I have nothing. I’m in despair. And it’s, like, twelve o’clock at night.

Now, Don Jose goes to bed when the sun goes down, in his little hut. But I look up and through my window I see him on the other side of the foliage, and it got me — what’s he doing awake? He was turned away, I could only see the back of his head. I went to the window, and he was just standing there. I went outside and I said, “Don Jose!” And he looked at me, and he was stricken. His face looked terrible. I said, “What’s wrong?” and he says, “I’m nothing, I’m shit!”

“What do you mean?” I said.

“What does your father do?” he asked.

I said, “He’s a doctor.”

“He’s a doctor, he went to school. Has he got a car?” “Oh yeah, he has a car — he has two.”

“Has he got a television?”

“Yeah, he’s got a television.”

“He’s got a home?”

“Yeah.”

“He’s a doctor. He’s a great man.”

“No, no, no. He’s not a great man.”

He said, “Well, he’s something, I’m nothing!”

I said, “Don Jose, you are wrong! You are one of the greatest people I’ve ever met. My father… my father is a drunk.” He would commit suicide a year later. I said, “My father doesn’t know who he is. He can’t live. You have knowledge, you have wisdom, you understand everything, you understand the earth, you see things, you see through everything, you’re brilliant.” And I kept talking to him, and he goes like this — “Really? Is that true?”

And I said, “Oh, Don Jose, you’re so lucky not to have a television.”

And he said, “Oh, I think I can sleep now — thank you, thank you!” And he went into his little hut. And I was transformed. I felt fine. I felt like a million bucks! I went back into the house and it hit me: he did that. He saw, he knew I was in trouble, and he knew how to get me out of it. He knew that if he could get me to love something outside of myself, to love him, I’d be okay. And that’s what he did. So that’s that “pray for rain” stuff for me.