He died while on the phone with one of his most enthusiastic lapdogs, his purported last words a fine banality: “Our destiny is to build a better future for our states.” An unworthy end, perhaps, for one of the most cold-blooded despots of the Levant’s twentieth century. There were a hundred thousand wishes that he might have died more painfully, tendered by the mothers, wives, and daughters of the men he detained, tortured, and killed over nearly thirty years of iron-fisted rule, but they would remain forever unfulfilled.

Hafez al-Assad (Arabic for “lion”), born al-Wahash (Arabic for “beast”) on October 6, 1931, died June 10, 2000. The official report announced he had died of heart failure; rumors, not entirely unfounded, claimed he died from acute acrimony over the Israeli withdrawal from south Lebanon — a move that deprived him of his most cherished bargaining chip in his never-ending negotiations with Israel. He was ruthless; he was patient. American presidents came and went, Israeli governments rose and fell, while the Sphinx of Damascus held court. He was a player. He knew when to hold them, and he could hold them indefinitely.

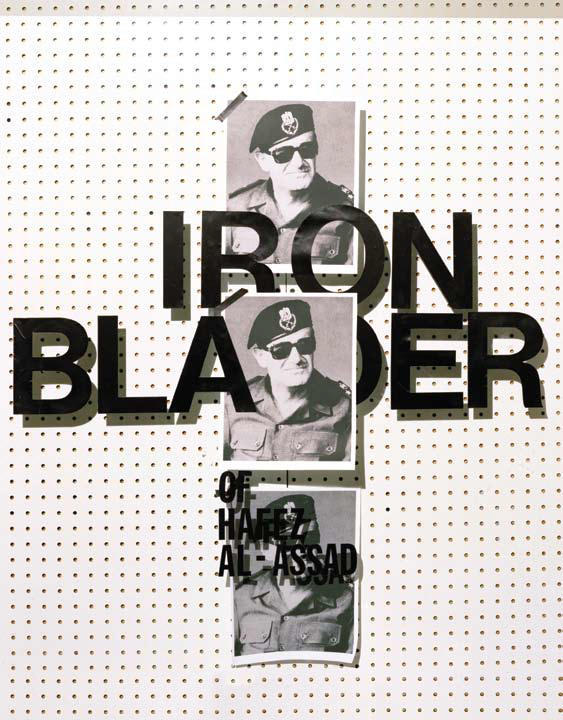

No wonder, then, that he had once been allotted a place in history as the founder of “bladder diplomacy,” a coinage of that ayatollah of modern diplomacy, Henry Kissinger. The sport of bladder diplomacy consists of hosting diplomats, negotiators, and state officials for meetings that can last up to nine hours, regularly serving them beverages — hot to cold — until, beside themselves, they are forced to bring the meeting to a conclusion, capitulating to some or most of their host’s demands, just to get to the loo. When Henry Kissinger, then the American secretary of state, met Assad for the first time, their encounter took six hours and thirty minutes. Kissinger was equal to the task. It is reported that the waiting press, unaccustomed to the modus operandi of bladder diplomacy, worried that the American official had been kidnapped. Decades later, another secretary of state, James Baker, was treated to nine hours and forty-six minutes without a break.

Assad’s tactic became so renowned that the unofficial duties of the American ambassador to Damascus included briefing dignitaries on how best to meet with the Syrian president: be careful when accepting gifts of coffee, tea, or lemonade, as even incidental encounters with the voluble host might be ruined if the guest defamed protocol by asking for a bathroom break.

In any case, according to a certain strain of conspiracy theorists, his bladder may have been his undoing. In February 1999, King Hussein of Jordan died, and his ostentatious funeral summoned an array of leaders nearly unprecedented in the region. It was Hafez al-Assad’s first visit to Jordan. The lion looked drawn and weakened. The conspiracy theory suggests that Israeli intelligence, in consort with the Jordanians, deployed a portable toilet special for the occasion, that they might seize a sample of the Syrian leader’s urine. They would then “read the tea leaves,” as it were, to find out the state of their mutual enemy’s health — whether he was ill, as suspected — and to make an educated guess as to how much longer the sixty-nine-year-old was likely to survive.

The magic of Assad’s negotiating style was not only his iron bladder. It was that he was always prepared to take no for an answer. In March 2000, when President Clinton presented Assad with Ehud Barak’s peace proposal in Geneva, the Syrian leader deemed it unacceptable. The round ended abruptly. All parties walked away empty-handed, the Americans furious.

And yet, over forty-eight hours in May of that year, the Israeli military withdrew from south Lebanon. Their presence there had long been used to justify Assad’s satrapy over Beirut; it was one of his strongest cards. But then suddenly, without signing agreements with either Lebanon or Syria, without the arduous process of negotiation, without a back-and-forth or long hours and nearly endless speeches, Assad was exposed. Some say that the Israelis had divined from his urine that his time was up. Cancer, diabetes, heart disease: he had months to live, a year at best. No better time to incur the wrath of the lion.

Two weeks later, he was dead.