We had been trying for a week to see Rashid Dostum, one of the most notorious of the Afghan warlords. We were hopeful; we had never gotten as far as this waiting room, with its canary-yellow walls and green brocade couches. But we had no idea how many other rooms still stood between us and the general.

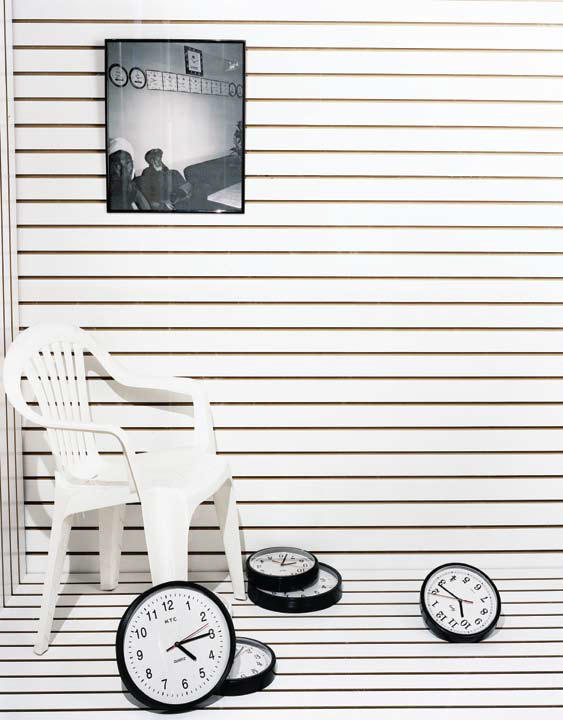

On the wall hung a row of clocks, some round and some square. Each one told a different time. Two white-bearded village chiefs sat silently, cross-legged on the couches, as though they weren’t couches at all but elevated patches of earth. An aide said that Dostum had acquired the couches in Turkey, where he had gone into exile in 1998 after his defeat by the Taliban. He returned at the end of 2001 with the support of the Americans to join the Northern Alliance in chasing the Taliban from power.

Everyone close to him agreed: the general’s tastes had evolved considerably during his forced exile in Ankara. The first order he gave after settling in Shebergan was to repaint this very building, which served as staff headquarters, a residence for his VIP guests, and the head office of the Jumbesh-e Melli, his national Islamic political party, entirely in pink. He also added two towers in the corners and ordered a crew of workers to rip out the street in front of the building, one of the only paved roads in all of northern Afghanistan, to plant flower beds.

His former stronghold, the Qala-i-Janghi (House of War) fortress, was a rectangular structure about half a mile long, made of crude bricks and ocher-colored mud and consisting of two huge courtyards surrounded by lookout towers and a double enclosure of ramparts and battlements. It overlooked the desert on the way out of Mazar-e Sharif. He used to like to punish traitors and criminals by having them crushed by his tanks in one of the courtyards. At the end of November 2001, Qala-i-Janghi was the scene of an uprising of three hundred Taliban prisoners, who were massacred by Dostum’s troops and American Special Forces. Only eighty-six of them survived, including John Walker Lindh.

The white-bearded elders disappeared. We were now alone in the room, wondering whether the American military officers who sometimes came to visit Dostum sat on these same couches, listening to the out-of-sync ticking of the clocks.

The clocks appeared to have been premiums for a chain-smoker who’d purchased in bulk. The square ones bore the name “Pine” and the round ones said “Legal.” These two cigarette brands, among the most common in Afghanistan, advertise “American taste” and “Blended in USA” on their packaging and are official products of South Korea.

All of the clocks worked except for the biggest one, which hung above all the others, its hands elegantly frozen at 10:10. No city names were given below the clocks to indicate the time zones to which they should correspond — New York, Paris, Beijing? Dubai, Peshawar, Tehran? They weren’t really keeping time at all, these clocks. It made the waiting seem even more interminable than it was.

Sometimes we would get up to knock on an adjacent door, only to be instructed to return to the couches, where we started to doze off. Behind the red curtains adorned with gold flowers, the day was rapidly coming to an end, and with it our chances for an interview.

Atta Mohammad, Dostum’s arch-enemy of the moment, also backed by the Americans, had been easier to approach. He had granted us an interview the day before in Mazar-e Sharif, dressed in a stylish three-piece suit and fervently insisting on his commitment to peace while fiddling with a bronze cannon, a miniature of those used during the Napoleonic Wars. He had just lost four villages to Dostum’s troops.

Our meeting with the general finally took place the next evening. Dostum allotted us ten minutes for a photo session in his office, which was decorated like an Oriental drawing room with a suspended gilded-stucco ceiling, subdued lighting, and an aquarium with no fish inside. As to the interview itself, he preferred to have us speak to his spokesman, who spent the next two hours telling us how the general was a man of peace, that he had not committed war crimes by letting Taliban prisoners die in containers abandoned in the desert, and that the Jumbesh was not financed by opium trafficking.

During our photo shoot, the general had agreed to answer one question only.

How had he found his office when he got back, after three years’ occupation by the Taliban? “Very clean!” he exclaimed. “They slept on the floor but didn’t damage the Persian rugs. When I left in 1998, I had forgotten a pair of shoes in a corner. I found them in the same spot when I came back, just a little dustier.” He pulled up his caftan so that we could admire his short black leather boots, shined to perfection.